|

New York Architecture Images-New York Architects Michael Arad |

|||

| New York works; | ||||

|

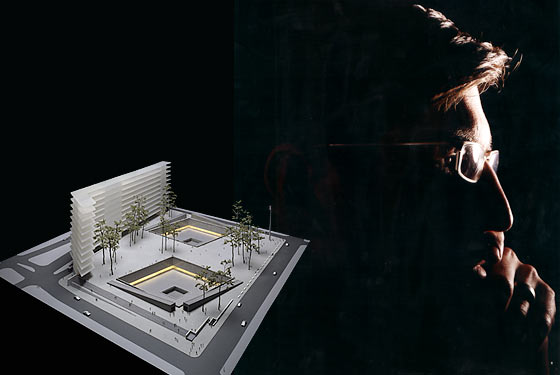

Michael Arad’s design for the 9/11 Memorial at the World Trade

Center site, titled “Reflecting Absence,” was selected by the Lower

Manhattan Development Corporation from among more than 5,000 entries

submitted in an international competition held in 2003. Mr. Arad joined

the New York firm of Handel Architects as a Partner in April 2004 where

he worked on realizing the Memorial design as a member of the firm. A native of Israel, Mr. Arad was raised there, the U.K., the United States and Mexico. He came to the United States and earned a B.A. from Dartmouth College in 1994 and a Master of Architecture from the Georgia Institute of Technology in 1999. Mr. Arad became a resident of New York City following his studies. He worked for Kohn Pedersen Fox in the city before joining the Design Department of the New York City Housing Authority, where he was working during the Memorial competition. In 2006, Mr. Arad was one of six recipients of the Young Architects Award of the American Institute of Architects. In 2012, he was awarded the AIA Presidential Citation for his work on the National September 11 Memorial. In addition, he was also honored in 2012 by the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council with the Liberty Award for Artistic Leadership. Michael Arad lives in New York City with his wife, Melanie Arad Fitzpatrick, and their children.  Architect and 9/11 Memorial Both Evolved Over the Years Michael Arad in Lower Manhattan at the site of the 9/11 memorial, which he designed. By TED LOOS, September 1, 2011 A FEW years ago the World Trade Center memorial was in trouble. Michael Arad, an unknown young architect, had won the design competition in 2004, and by 2006 the estimated cost of the memorial and related projects had nearly tripled, to close to a billion dollars. Construction had still not begun. The project seemed to be “spinning out of control,” according to an article in The New York Times in May 2006; that same month, a long profile of Mr. Arad in New York magazine had it teetering on “the brink of collapse.” It was always clear that there were too many people and organizations with conflicting interests involved in the World Trade Center site for anything there to go smoothly. But some people thought that as good as Mr. Arad’s design was, the architect himself was part of the problem.  Mr. Arad, a former Israeli soldier (he is a dual Israeli-American citizen) who once considered becoming a lawyer, had been in fighting mode almost from Day 1, publicly battling with the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation over creative control and infuriating other architects on the ground zero project, some of whom described him as intransigent and ego driven, without the experience to compromise and roll with the punches. In a recent interview Peter Walker, the landscape architect on the memorial, recalled Mr. Arad “screaming and walking out of a room” in those early days. “It happened many, many times,” he said. (For his part Mr. Arad said there were no tantrums, just “heated discussions.”) Five years later the memorial component of the National September 11 Memorial and Museum is just about finished, and scheduled to open next Sunday. (The museum is to open next year.) Early reviews have been largely positive; in the view of the Los Angeles architect Thom Mayne, who consulted briefly on the project, the final product “has a solemnness, a simplicity and an otherness which is absolutely perfect.” Like everything else about ground zero, the story of how the memorial got back on track is complicated, and involves many players. But it is also at least partly the story of Mr. Arad’s evolution from a hot-headed 34-year-old novice whose design bested some 5,200 others to the more sanguine and battle-tested — if still perfectionist — architect he is today. It’s a tale that surprises many of those associated with the project, not least Mr. Arad himself. “When I started this project, I was a young architect,” said Mr. Arad, 42, as he toured the site during the summer. “I was very apprehensive about any changes to the design. Whether I wanted to or not, I learned that you can accept some changes to its form without compromising its intent. But it’s a leap of faith that I didn’t want to make initially — to put it mildly.”  “I had a dual role: designer and advocate,” said Mr. Arad (pronounced ah-RAHD), who comes across as thoughtful and intense. The memorial occupies about half of the 16-acre World Trade Center site, which is a busy place these days, with four towers in various stages of construction. It includes a plaza with more than 400 swamp white oak trees, an area that will serve as a green roof over an underground museum designed by Aedas Architects with an entrance pavilion designed by the Norwegian firm Snohetta. (The budget for both memorial and museum is now down to $700 million.) Most significantly, the footprints of the original World Trade Center towers have been turned into two square, below-ground reflecting pools, each nearly an acre, fed from all sides by waterfalls that begin just above ground level and bordered by continuous bronze panels inscribed with the names of those who died there and in Washington and Pennsylvania. Mr. Arad, who started designing a memorial before there was even a competition, was invested from the start in making what he called a “stoic, defiant and compassionate” statement. Born in London, he had grown up all over the world as the son of an Israeli diplomat who was once ambassador to the United States, and has lived in New York since 1999. He watched the second plane hit the World Trade Center from his roof on the Lower East Side and saw the south tower fall from a few streets away. “I think my desire to imagine a future for this site came out of trying to come to terms with the emotions that day aroused,” he said. That personal investment, along with his considerable determination, led him to make waves even in his initial proposal, which deviated from the ground zero master plan — essentially a blueprint establishing guidelines for all architects working at the site — drawn up by the architect Daniel Libeskind. If the competition jurors were impressed by Mr. Arad’s boldness of vision, Mr. Libeskind seemed to be less so; the 2006 article in New York magazine recounted an early shouting match between the two men. Whatever resistance he offered to Mr. Libeskind’s plan, Mr. Arad balked at proposed alterations to his own, especially early on, according to some of those involved. “Michael was constantly fighting a rear-guard action,” Mr. Walker said. “Every time somebody would make a change, it really hurt him. “I think it was because he was young. If he couldn’t get somebody to do it the way he wanted it done, he couldn’t see that there was an alternative.” The proposed changes were many, since state, local and federal officials were involved, as well as the Port Authority of New York and New Jeresy, the developer Larry Silverstein and the state-city Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, among others. Mr. Mayne, who was brought in by the F. J. Sciame Construction Company to advise on ways to lower the project’s cost, called it “the architecture of negotiation.” Cost and security concerns led, in 2006, to the biggest blow to Mr. Arad’s original design: the loss of what he called the memorial galleries, below-ground walkways in the footprints where around the falls, whose walls of water would serve as shimmering backdrops to the names of the dead near floor level. Now visitors would have to remain above ground. “That felt like a tremendous blow,” Mr. Arad said. “Do you walk away from a project after a defeat like that? Or do you find a way to come to terms with the new parameters?”  He did so, but not easily at first. “When they moved the names up, he was in a real funk, and I don’t blame him,” Mr. Walker said. “He was hard to deal with for a while because he was so upset about it.” Mr. Libeskind, now conciliatory, said that Mr. Arad was not prepared for the setbacks he would face, “but no one could have been,” since the process was grueling for everyone, including himself. “Michael learned quickly, and there was no time to waste,” he added. “There were forces that could come in to supplant any idea.” One of the things Mr. Arad learned was how to make the most of relationships with allies. At first he didn’t have all that many. But in 2006, when Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, a fan of Mr. Arad’s design, became chairman of the memorial foundation (which took over from the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation as the governing body on the project), several of his representatives on the project began to rally for the architect, notably Deputy Mayor Patricia Harris and the director of the Department of City Planning, Amanda Burden. “I wanted to make sure every intention Michael had was realized,” Ms. Burden said. But that kind of support might not have lasted had Mr. Arad not been smoothing out his political game. “I built a series of supporters that had my back,” Mr. Arad said. “I never abused that trust. You can’t cry wolf. You have to solve most problems yourself.” A test of his more moderate approach came in dealing with one of the world’s most famous architects, Santiago Calatrava. His design for the World Trade Center transit hub, expected to open in 2015, involved extensive skylights over the underground station that would have looked up through the memorial plaza and formed part of its surface. Mr. Arad thought it was an “incredibly aggressive gesture” that would have ruined the memorial. But instead of yelling, he went to the mayor’s representatives about it, “sometimes openly, and sometimes through back channels,” and also met several times with Mr. Calatrava in his home. Mr. Arad proposed a compromise scheme with fewer skylights at one point and even asked Mr. Calatrava to lend his drawings so he could study them. Mr. Calatrava said that Mr. Arad convinced him, and other changes to the site plan around the same time sealed the deal. The skylights were scrapped. “I understood that in this particular place, the memorial is more important than the station,” Mr. Calatrava said. Yet the thorniest issue of all was yet to come. “The only really contentious issue was the placement of the names,” Mr. Bloomberg said in a phone interview, adding that through it all, Mr. Arad “never got excited or yelled at anybody.” Mr. Arad had long advocated a concept he called “meaningful adjacency,” meaning that victims who knew one another or perished close to one another would be listed in close proximity. But for a time no one else agreed, and the plan was to list them randomly. “For two years nobody talked about anything other than the name arrangement,” Mr. Arad said. “There was no fund-raising and no progress being made on construction and design.” The mayor got personally involved, suggesting his own version of adjacency and allowing time for Mr. Arad’s plan to gain traction. Once Mr. Arad’s original version triumphed, after dozens of meetings, Mr. Arad and a colleague at Handel Architects, the firm where he is a partner, spent more than a year working out the arrangement of names. In the end they were able to meet all 1,200 location requests that were received from the families. Gary Handel, the founder of Handel Architects, said that experience has mellowed Mr. Arad. “Three years ago, when it became clear this was really going to happen, he got a little more calm and confident,” Mr. Handel said. Mr. Arad agreed with Mr. Handel that the process and the years have changed him. “I’m a little more measured,” he said. “That sense of urgency I thought accompanied things — it can take a little longer. You have to take the long view.” Mr. Arad pointed to one relationship in particular that had improved with time and demonstrated his ability to put the past behind him. “Daniel and I are talking about doing a project,” he said of Mr. Libeskind. “That’s a nice way to end this eight-year process, to say, ‘Hey, let’s do something together.’ ” A version of this article appeared in print on September 4, 2011, on page AR1 of the New York edition with the headline: Architect and 9/11 Memorial Both Evolved Over the Years. Copyright NYT |

||||

|

links |

||||