|

New York Architecture Images-Brooklyn New York State Pavilion (1964-1965 World's Fair) |

|||||||||

|

architect |

Philip Johnson & Richard Foster Architects (Zion & Breen Associates, Landscape Architects) | |||||||||

|

location |

Flushing Meadows Corona Park Queens NY | |||||||||

|

date |

1964 (1982 Interior renovation Philip Johnson/Burgee Architects) |

|||||||||

|

style |

Futurist | |||||||||

|

construction |

||||||||||

| With special thanks to http://www.jetsetmodern.com/index.htm | ||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

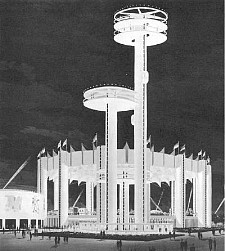

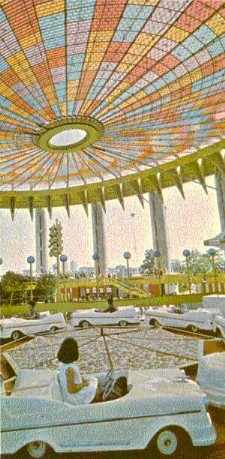

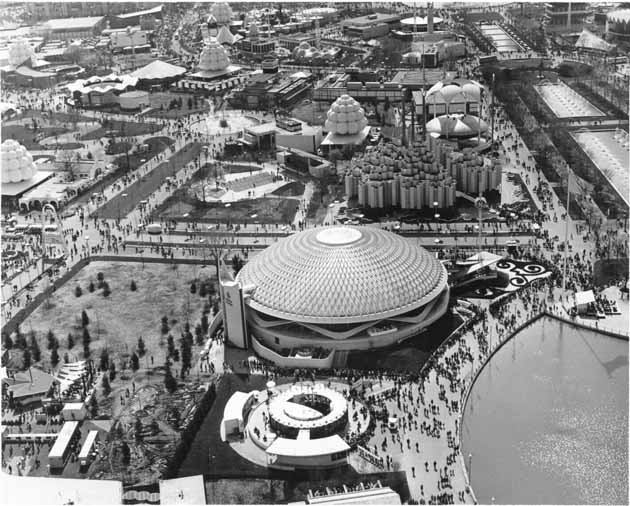

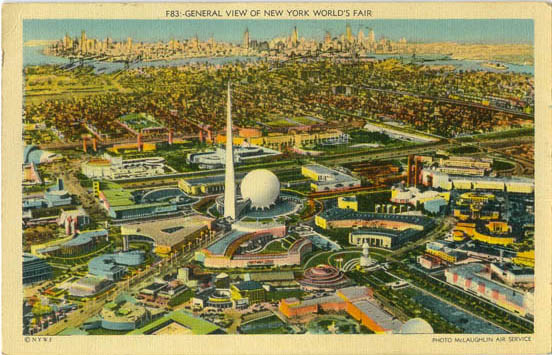

| Yesterday (Source: FAIR NEWS Official Bulletin of the New York World's Fair 1964/1965 Vol. 1, No. 5 - Oct. 16, 1962) | Today (photo: CREATE) | Yesterday (Source: National Geographic Magazine, April 1965, Vol. 127 No. 4) | ||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

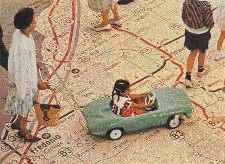

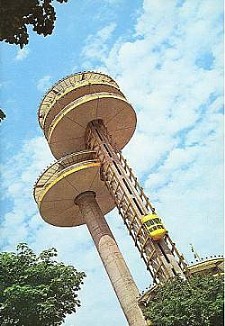

| Yesterday (Source: Official Post Card, Dexter Press, West Nyack, NY) | Yesterday (Source: 1965 World's Fair Publicity Pamphlet, "What's Free at the Fair") | Today (photo: CREATE) | ||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

| Today (photo: CREATE) | Today (photo: CREATE) | Today (photo: CREATE) | ||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

Commissioned by the state of New York for the

1964 World's Fair in New York City (Queens), the New York State Pavilion

was the largest in the Fair, and is one of the few structures from the

Fair to remain standing today. The Pavilion was dedicated the day after

the New York State Theater, and came at a time when Johnson's break from

strict Miesean vocabulary was becoming evident.

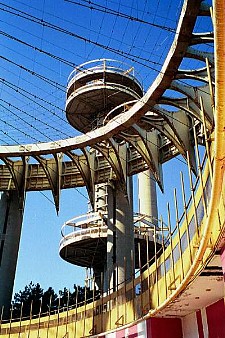

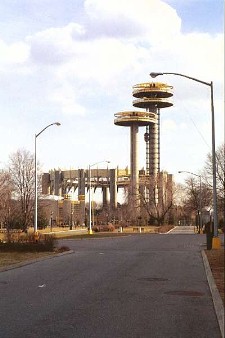

The New York State Pavilion consists of three main components, each with its own purpose, rather than being one single building intended for multiple uses. The largest structure in the complex is an elliptical plaza measuring 350 feet by 250 feet. This space is surrounded by 16 steel columns (each one hundred feet high), which once held up a colorful canopy that covered the plaza underneath.

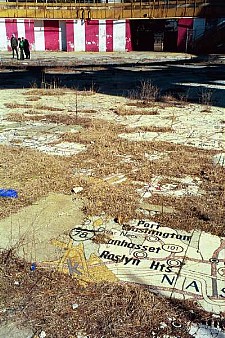

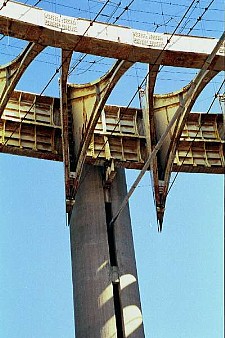

An oversized map of the state of New York, which is made up of 567 mosaic terrazzo panels weighing about 400 lbs. each, largely covers its floor. The map is said to have cost one million dollars at the time, and displays the locations of all Texaco gas stations in the state of New York. Perhaps the most impressive structures in the Pavilion (and the most recognizable) are the three observation towers measuring 90, 185 and 250 feet tall. These observation towers were reached by capsule-shaped elevators (which can still be seen on the sides of the towers), and were the tallest structures at the Fair. Lastly, a circular theater, 100-foot diameter, known as the Circarama sits along the towers. The theater was used to show a 360-degree film about the state of New York during the fair. Johnson commissioned Peter Agostini, John Chamberlain, Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Roy Lichtenstein, Alexander Lieberman, Robert Malloy, Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist and Andy Warhol to install paintings and murals on the outside of the Circarama. At the time these artists were relatively unknown to the masses, and in many cases were still considered controversial.

Today, the New York State Pavilion is perhaps more impressive than it was during the World's Fair. It stands as a piece of architectural ephemera; a relic that somehow continues to stand decades after its intended use has passed. This aspect of the Pavilion is of particular interest, especially if one takes into account Johnson's well-known passion for architectural ruins. In his foreword to "The Architecture of Philip Johnson" he writes:

Efforts have been made to save the Pavilion by using it once again, and at least one of them has been successful. The Queens Theatre took over the circular Circarama adjacent to the towers in 1994 and continues to operate there. As for the rest of the Pavilion, many uses have been proposed, including an air and space museum but no concrete plans have been made for the decaying structure yet. As a result, the towers and the large elliptical plaza that was once covered remain unused and padlocked (in the day of my visit, a worker was kind enough to let me enter briefly). The map of the state of New York, which was open to the public until sometime in the 1980's, is almost completely destroyed in some areas, since it is now unprotected from the elements (as are badly rusted escalators and handrails) and lays literally in pieces. Inside, large red stripes that were painted on the walls can still be seen, along with round planters/benches that surrounded the map. As it stands today, the Pavilion is a beautiful structure, perhaps one of my favorites in all of New York City. The Pavilion is a fantastic mix of architectural optimism from another time, with the financial realities of a city like New York. How to visit The New York State Pavilion is located within Flushing Meadows Corona Park in Queens, New York. The easiest way to see visit is by taking the 7 train to the "Willets Point-Shea Stadium" stop in Queens. Walk south and you will see the three towers. The Pavilion is less than 10 minutes by foot from the station, near the Unisphere. During the nighttime, the park can be a bit unsafe, particularly if you don't know your way around too well. There is a small parking lot adjacent to the Pavilion (a New York City rarity) so that driving is also a possibility. Directions are available at www.queenstheatre.org/directions/index.html. Note that due to its proximity to Shea Stadium, the USTA National Tennis Center and La Guardia Airport, traffic can be unusually bad at certain times, even by New York standards. |

||||||||||

Thanks to Jeffrey Stanton 1997 |

||||||||||

|

Author: Bill Young

In 1933,

then Parks Commissioner Robert Moses was directed to find a spot where

New York could hold a World’s Fair. He didn’t have to look far. He had

in mind a location that had intrigued him for many years. The site was

the location of the great Corona Dumps, an area of land just to the

south and east of Flushing Bay in the Borough of Queens and located at

the exact geographic center of the city of New York. It was his dream to

create New York’s greatest Park and this would be the place.

Never one to miss an opportunity to develop, Moses

soon acquired the land and set about transforming a marshy lowland

garbage dump into the glittering Fairgrounds of the 1939/1940 New York

World’s Fair from which the profits would allow him to realize his grand

scheme. Unfortunately, the Fair of ’39 and ’40 turned out to be a

financial bust and Moses’ dream went unrealized.

Twenty-five years passed and Mr. Moses was once

again called upon to transform this same piece of Queens real estate

into the Fairgrounds of yet another World’s Fair. This time it was the

Space Age extravaganza of 1964/1965. Although this Fair also turned out

to be a financial flop, Moses managed to scrape enough money together to

somewhat advance his dream for the great Park. But its glory days were

yet to come.

Now, nearly 40 years later, Flushing Meadows-Corona

Park can rightfully boast that it has become New York’s Great Park. It

is Queen's largest park and one of New York's flagship parks. Home to

the New York Hall of Science, the Queens Museum of Art and the Queens

Theater in the Park, it is the Park of museums and culture as well as

sports and recreation. Here you will find the National Tennis Center’s

Arthur Ashe Stadium and work is underway to build a $35 million aquatic

center and ice rink in the Park’s northeast corner. The Unisphere, the

12-story high stainless steel globe that was the 1964/1965 Fair’s

symbol, has been refurbished and given Landmark status. On the Lake side

of the park a children’s story garden area is under construction on the

site of the old amphitheater of the 1939 World’s Fair. All this is a

part of an on-going renaissance in which even the Park fountains once

again splash in pools and basins.

But quite literally beneath the

culture and recreation and museums and playing fields lies Flushing

Meadow’s darkest secret - one that many know nothing of or fail to

realize. Flushing Meadows is built on a garbage dump that covers a

swamp. And perched precariously on this weak and shifting ground is a

building that has somehow been overlooked in the Park’s renaissance. It

is an abandoned and derelict legacy of the 1964/1965 World’s Fair:

Philip Johnson’s towering New York State Pavilion.

New York’s exhibit for the Fair

was conceived as “The County Fair of the Future.” Of course this was to

be America’s “Space Age” World’s Fair and everyone seemed to be touting

“TOMORROW” in one form or another. Johnson’s structure was no exception

with the design being reminiscent of something out of a Jetsons' comic

book. The pavilion consists of three principal structures: the circular

Theaterama building, the “Tent of Tomorrow” and three observation

towers, the highest at 226 feet, providing Fairgoers with a panoramic

view of the grounds.

The “Tent of Tomorrow” was the heart of Johnson’s

pavilion. An elliptical shaped, 350-foot by 250-foot structure, whose

outer support of sixteen 100-foot tall, white concrete columns, made it

one of the largest buildings at the Fair. The Tent featured the world's

largest suspension roof. And on the floor, the world’s largest road map

- the State of New York done in terrazzo. After all, this was Nelson

Rockefeller’s New York State Pavilion showcasing his state. Everything

was required to be the tallest, the largest and the best.

The pavilion is completely open save for the first

two floors topped by a mezzanine walkway. The suspension roof made of

translucent fiberglass panels done to resemble stained glass kept out

some of the elements. But the building, for all practical purposes, is a

12-story high open-air structure.

Construction for the pavilion began in October,

1962. One of the first steps in the construction process for all

pavilions was to call in the pile drivers. To build something of any

size on the site required 18-inch wooden piles to be driven into the

marshy ground for building support. Picture huge telephone poles lined

up in rows at the sites of construction. Some contractors working on

site reported that some of their piles simply disappeared as they were

driven into the ground, so unstable was the ground these buildings were

being built on.

No matter. The Fair was temporary - meant to last

only two years. Wooden piles were surely good enough for such a short

time frame. Moses was building his Fair with an eye to the future and

had already decided that structures built for the Fair that did not have

useful post-Fair park purposes would have no place in the post-Fair

park. So all exhibitors signed the same lease that said their pavilions

were to be demolished within 90 days of the close of the Fair in

October, 1965. The New York State World’s Fair Commission no doubt

signed that lease as well.

But somewhere in the early construction phase,

someone had an inkling that this building might serve a useful park

purpose someday. Or maybe someone realized that the taxpayers of New

York would be footing a pretty big bill to construct such a structure

for the Fair. Perhaps they would not be too happy to see all of those

tax dollars reduced to rubble after two short years. The Landmark

Preservation Commission in 1995 noted that it stayed because it was too

expensive to tear down. Whatever the reason, it is believed that steel

piles were driven into the ground to support the New York State Pavilion

along with the wooden piles. However, their exact location was never

documented.

The two years of the Fair came and went. Johnson’s

design was praised for its innovation and simple sophistication; winning

an “Honorable Mention” award for Excellence in Design by the New York

Chapter of the AIA. Photos of the pavilion during the Fair show a

colorful structure that was popular with the crowds and served its

exhibit purpose well. Nighttime shots of the pavilion show how

spectacular illumination made the pavilion seem almost cathedral-like as

lighting suspended from cables above the translucent roof created a

dazzling stained glass effect.

In the summer of 1965, a special commission

established by New York’s Mayor Robert Wagner submitted a list of

pavilions they thought should remain to serve the park. Among them was

Johnson’s New York State Pavilion. The Commission felt the towers

constituted a natural tourist attraction. The Theaterama building would

be a great marrionette theater and the “Tent of Tomorrow” could provide

a covered area for athletic events, concerts and dancing. Robert Moses

thought it would make a good “art museum.” So it stayed while the rest

of the Fair went away.

Money was eventually spent to refurbish parts of the

pavilion to display art. And for a brief period following the Fair,

there were a few art exhibits shown. The Byrds played a concert there

once. So did the Grateful Dead. From 1970 to 1974, a roller rink

operator from Ohio operated the pavilion as a popular outdoor roller

skating rink called the Roller Round. The million dollar terrazzo map

was plastic coated to protect the surface from the skaters. Talk was

that the World Trade Center, then under construction, would be

interested in having the map as a part of their grand courtyard. But it

never happened. The floor stayed. The towers were never opened.

In the early years, Park inspectors paid close

attention to the pavilion coming around every so often to inspect the

roof and the floor and the building in general. Security patrols

regularly followed a beat and the Park stayed a place for recreation and

fun. But after 1974, things started to change for the Pavilion, the Park

and the City of New York. The Roller Round closed after a dispute over

who was responsible for maintenance forced the rink operator to suspend

operations and the pavilion sat empty once again. The great financial

crisis of the mid-seventies hit the Park with a vengeance. The city was

broke. There was no money for many things, but especially not parks.

Gone were the inspections. Gone were the funds for

maintenance and improvements and security patrols. And gone were ideas

for finding a useful purpose for Johnson’s pavilion. The open-air

concept that had been called so innovative for a World’s Fair pavilion

was now a drawback for finding an appropriate post-Fair use. The Park

soon became home to derelicts and drug pushers. No one else came by

anymore. In 1976, the other major structure salvaged from the Fair, the

Federal Pavilion, was demolished because vandals had nearly destroyed

that structure from the inside out. That pavilion had never found a

post-Fair use.

In 1977, lack of maintenance and the effect of wind

sway caused the panels of the suspended roof to become loose. After

several blew off and onto the Grand Central Parkway, the roof was

ordered removed from the structure. The cables left as a ghostly spider

web.

The terrazzo map was now exposed completely to the

elements. Vandals picked away at it removing whole sections of New York

City and Long Island. Slowly the blue glass globes lining the outside of

the pavilion and towers and rails were broken by stones and rocks. Bird

droppings in the open stairwells caused whole sections of stairway to

disintegrate and break away so that climbing the stairs to re-lamp the

warning light at the top of the tallest tower that warns planes on

approach to LaGuardia became a rope climbing exercise.

Year after year after year the building sat and

deteriorated. Two major motion pictures, “The Wiz” and “Men in Black,”

used the pavilion as a setting. But once the camera crews were gone, the

cosmetic repairs to make the rusting old hulk look good in the

close-ups, disappeared along with the actors. The Parks Department

applied an occasional coat of paint to slow the rust and hide the

deepening scars.

Today, to the naked eye, the pavilion is a disaster.

The lower level of the mezzanine is beginning to separate from the

building. Huge cracks run through the cinder-block walls. The elevator

towers are rusted. One “Sky-Streak” elevator sits smashed in the service

well at the base of the tall tower while the other has been suspended in

mid-air for 30 years. The vandals have even managed to scale the tower

far enough to smash in its windows and protective bars.

The steel crown at the top of the structure that

supports the suspension cables that support the roof is rusting badly.

Soon, the tension cables will begin to snap which could result in the

catastrophic failure of the entire crown.

The map is beyond repair. Parks Department personnel

have patched the missing terrazzo with concrete patches. The rest of the

terrazzo is as crazed as an old piece of porcelain. Weeds and plants

grow between the cracks and it seems every Spring an abandoned car is

found inside despite the chain-link and padlocks used to keep

trespassers out.

The former Theaterama building was renovated several

years ago and serves as the Queens Theater in the Park. The New York

State Pavilion’s only role now is a storage shed for the Theater.

Outside, the curious stand looking up, shaking their heads in disgust.

But the real problem with Philip Johnson’s pavilion

cannot be seen. The problem that goes all the way back to 1933 and the

creation of what would become Flushing Meadows Park. It is what is going

on underground and unseen that is most troublesome. Engineering reports

dating back to 1992 indicate that those old wooden piles are

deteriorating and deteriorating badly at that. Given that the ground the

building stands on is so precarious, those sixteen massive 100-foot tall

columns need all the support they can get. Geotechnical firms have

recommended, in 1992, 1996 and in 2001, that the structure either be

stabilized or demolished. To date, the City of New York and the Parks

Department have done nothing.

It has come to that for Philip Johnson’s building.

Recent estimates to stabilize the pavilion are in the $7 - $10 million

range. The pavilion has reached a crossroads. In order to justify that

type of expenditure, a use has to be found for the pavilion now. It

would help if an effort could be started to seek Landmark Status for the

pavilion. But simple safety concerns for the people who use the Park

demand that something more than Landmark Status must protect the

pavilion - and the public. Either money has to be found to stabilize it

or it must be demolished.

At the eleventh hour, someone has

come up with a plan for the pavilion. The proposal is to adapt the

original structure for use as the new Air & Space Museum. (For details,

please visit:

http://www.nywf64.com/savenys03.2.html).

The plan is so obviously "right" that it's

surprising it hasn’t been proposed before. The plans have been presented

to the Parks Department and the Office of the President of the Borough

of Queens and have generated much interest. But along with those

presentations have come the warnings of dire consequences if the

stabilization problems are not addressed NOW. And the Parks Department,

like a sleeping giant, is waking up to the concerns. Will they act to

save the structure? Or will they simply be rid of it and all its

problems?

The easy way out would be the demolition. But the

building IS worth saving. From an architectural standpoint. From a

historical standpoint. From a cultural standpoint.

This article is meant as a wake-up call to all those who would help to

save the pavilion. Contact Queens Borough and Parks Department

representatives in New York to budget money for its' stabilization.

Putting pressure on the deed-holders to save it is the only alternative

to its certain demolition.

The pavilion is now a modern ruin. If action is not

taken soon, there won’t even be a modern ruin to enjoy.

and

www.inch.com/~buehler/ruins/fair

Contact Frankie Campione at CREATE Architecture,

Planning, Design New York, NY. Email:

FCampione@CreateAPD.com

Please support the efforts to save this

architectural landmark. With special thanks to http://www.jetsetmodern.com/index.htm |

||||||||||

|

links |

More about the 1964-65 World's Fair. | |||||||||