|

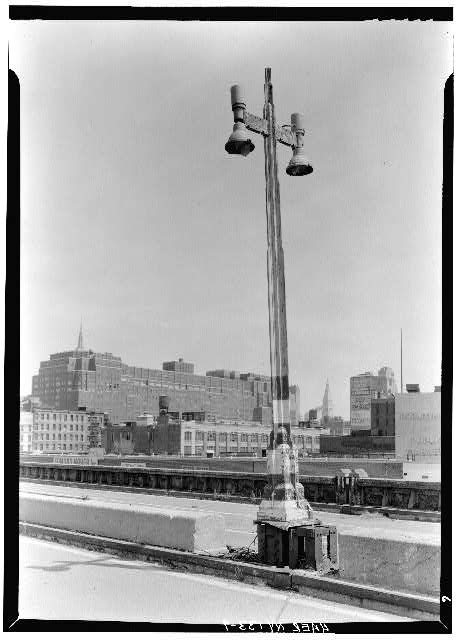

New York Architecture Images- Gone West Side Viaduct (Miller Highway) |

|

architect |

Public Works (Robert Moses) |

|

location |

West side |

|

date |

1933 |

|

style |

Art Deco |

|

construction |

Steel |

|

type |

Utility |

|

images |

|

|

|

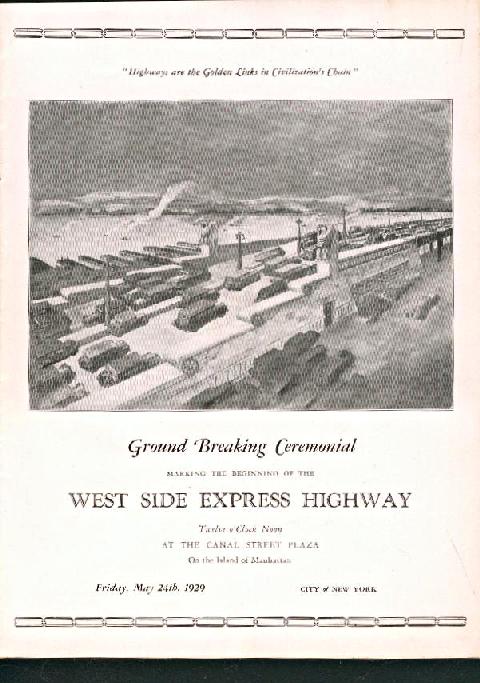

Ceremony booklet

from the May 24th 1929 Ground breaking at Canal St. The booklet says that on May 2nd from 21 bids, the contract was awarded to James Stewart & Co to build the elevated highway from Canal St to 72nd St., 4 miles worth in the amount of $4,547,449.60 I wonder what the sixty cents was for... According to another source; The highway from West 72nd Street south to Chambers Street was constructed between 1927 and 1931. It was extended south from Chambers Street to the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel approach between 1945 and 1948 Demolition of the elevated highway started in 1977- 4 years after a section collapsed under the weight of a cement truck, the demolition was completed in 1989. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

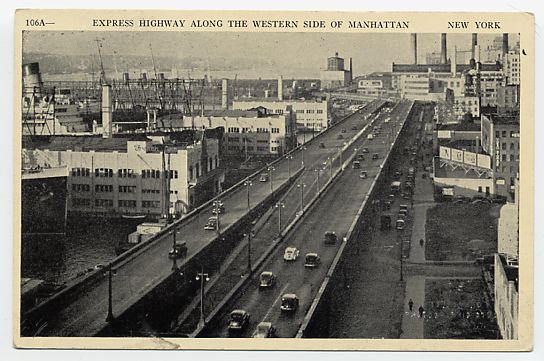

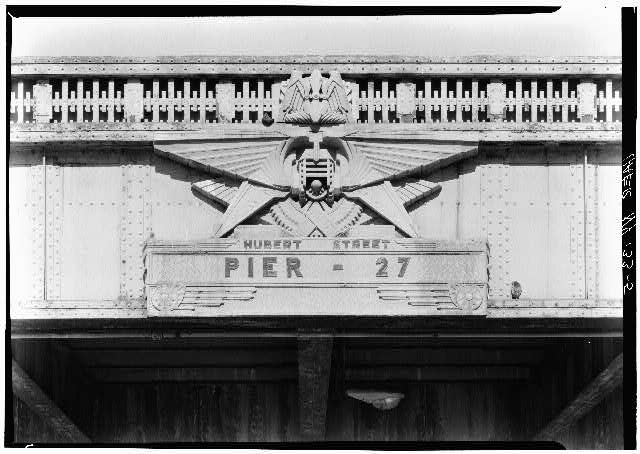

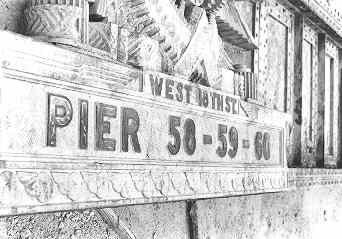

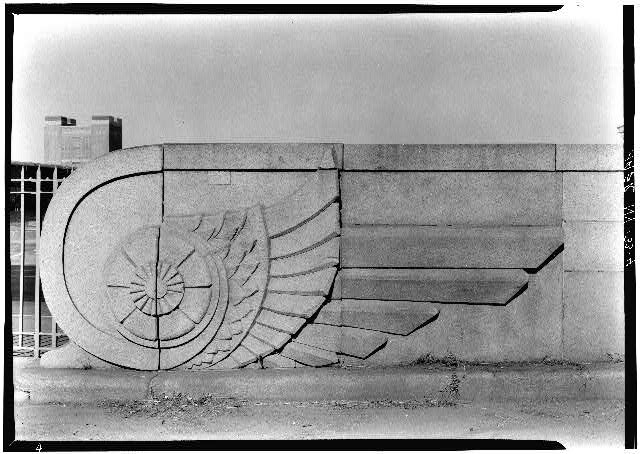

| THE

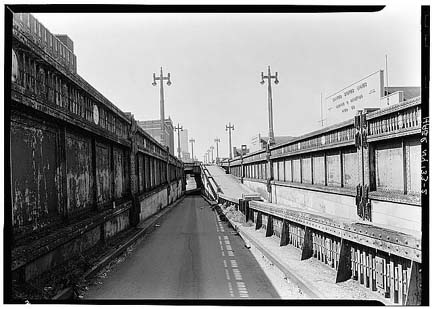

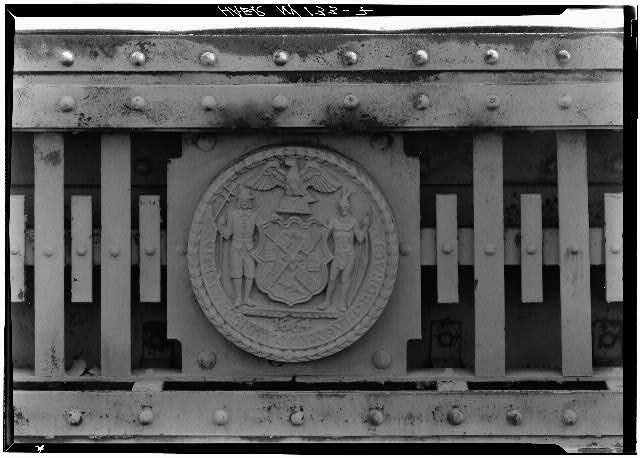

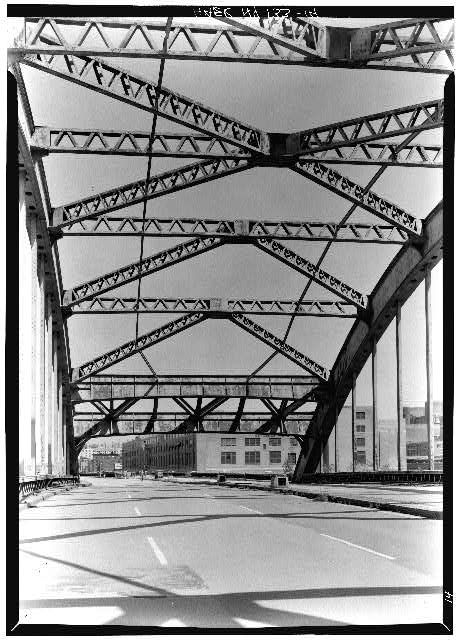

ORIGINAL WEST SIDE HIGHWAY: For

nearly five decades, the line of demarcation between the Hudson River shoreline and the interior of Manhattan was the elevated structure of the West Side Highway. The West Side Highway, originally designated NY 9A north of the Holland Tunnel and NY 27A south of the Holland Tunnel, was part of a limited-access, automobile-only system of parkways conceived by New York's master planner, Robert Moses. The original elevated highway from West 72nd Street south to Chambers Street was constructed between 1927 and 1931. It was extended south from Chambers Street to the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel approach between 1945 and 1948. When the highway, known officially as the Miller Elevated Highway (named after former Manhattan Borough President Julius Miller), was constructed, it was well suited to its purpose and location. Its elevated structure allowed trucks to travel between the piers to its west and the factories and warehouses to its east, while automobile traffic was unimpeded overhead. To avoid buildings on either side, the highway was constructed with sharp curves and narrow entrance-exit ramps. The design of the highway, while inadequate for today's needs, was not an overriding concern at the time. Even on limited-access highways, speeds often did not exceed 35 to 40 miles per hour. Indeed, one of the reasons that the highway was constructed was to afford motorists a scenic route from the Battery to Westchester County. EARLY PLANS TO IMPROVE THE WEST SIDE HIGHWAY: The deterioration and obsolescence of the West Side Highway were recognized as early as 1957, when the first of six studies on improving the elevated road was published. By that time, traffic counts on the West Side Highway had already measured 140,000 vehicles per day (AADT). The initial 1957 study, which was conducted by the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (TBTA), called constructing three lanes in each direction throughout the length of the route, realigning the highway's sharp "reverse-S" curves, building new interchanges for the Holland Tunnel and Lincoln Tunnel approaches, and improving the exit ramps at West 23rd Street and West 59th Street. Completion of this $22 million project was scheduled for 1964. A more ambitious reconstruction of the West Side Highway was recommended in a 1965 study, also conducted by the TBTA. The recommended improvements were stated as follows: From the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel north to the Holland Tunnel, the existing six-lane elevated highway would have been refurbished. New direct access and exit ramps would have been constructed to the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel (I-478), and to the proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway (I-78). From the Holland Tunnel north to the Lincoln Tunnel, the elevated highway would have been refurbished, and widened from six to eight lanes. In the vicinity of West 23rd Street, the highway would have been realigned to eliminate the "reverse-S" curve. New direct access and exit ramps would have been constructed to the proposed Mid-Manhattan Expressway (I-495). From the Lincoln Tunnel north to West 59th Street, the elevated highway would have been refurbished, and widened from six to ten lanes. In the vicinity of West 42nd Street and West 57th Street, the highway would have been realigned to eliminate the "reverse-S" curves. North of West 59th Street, the refurbished elevated structure would have transitioned from the ten-lane, 5-5 alignment of the West Side Highway to the proposed 3-2-3 alignment of the upgraded Henry Hudson Parkway. A new exit would have been constructed at West 65th-West 66th Streets for the proposed Lincoln West development. Throughout the entire length of the highway, 11-foot-wide lanes would have been provided. Left-hand exits would have been replaced with right-hand exits, and adequate acceleration-deceleration ramps would have been constructed. After completion, access to the West Side Highway would have remained restricted to passenger cars. Trucks and buses would have used a widened West Street underneath the elevated highway. The $76 million widening project, originally scheduled for completion by 1972, was never constructed. The sixth and final study, which was conducted in 1971 (the "Wateredge" plan), proposed constructing a replacement highway built on pilings and platforms in the area between the edge of land at the bulkhead line and the ends of the piers at the pierhead line. Moses, who built the original West Side Highway, was instrumental in developing plans for its replacement. DETERIORATING BEYOND REPAIR: In its 1966 report Transportation 1985: A Regional Plan, the Tri-State Transportation Commission made the following recommendation for the West Side Highway: Throughout New York City, as well as in certain other portions of the region, there is an urgent need to replace and reconstruct outmoded and worn-out facilities. The city is unique in its need for highway renewal as well as urban renewal, for it has many early facilities that have undergone long and heavy usage. The prime candidate for replacement is the West Side Highway, whose tortuous curves and constricting width are far below modern design standards required for better speeds and higher volumes. The changed face of the City's waterfront also provides the opportunity to coordinate this highway reconstruction with potentially new and more appropriate uses of adjacent land. In such a case, highway renewal coupled with new land uses provides an unparalleled opportunity for civic improvements. The inadequacies of the West Side Highway had become more acute by the early 1970's. The narrow ramps, left-hand entrance-exit ramps, sharp curves, and a crumbling structure posed serious hazards. Because of these hazards, cars could not travel at the speeds common on other area highways. Furthermore, trucks were prohibited from using the highway due to the inadequate size, shape and strength of the ramps and elevated structure. As New York City entered fiscally dire straits, it became more difficult for the City simply to maintain the existing highway in its deteriorated condition. Ralph Herman, frequent contributor to nycroads.com and misc.transport.road, added the following on the original West Side Highway: The roadway was cobblestone... It was originally designed as a four-lane highway, and in later years was marked as a six-lane road. I remember around 1970, the roadway was reduced back to four lanes in the area of the hairpin curves, where the speed was reduced from 40 MPH to 25 MPH. It was a challenge to hold on to the steering wheel at 40 MPH with those cobblestones, and was extremely slick when wet. During heavy rainstorms, the tiny sewer gratings would clog up with road debris and silt, causing water to collect on the roadway at "low points" on the elevated structure. Because the curbing was so high, the water could get deep -- about a foot or so -- slowing traffic to a crawl. This was probably one of the few elevated roads that could be blocked due to flooding during a rainstorm! END OF THE HIGHWAY: On December 16, 1973, in the most ironic of circumstances, a cement truck that was traveling to make repairs on the West Side Highway caused a 60-foot section of the northbound roadway to collapse at Gansevoort Street. Immediately, the entire highway from the Battery north to West 46th Street was closed. Subsequent to the collapse and closure of this section, engineering inspections were made to determine if repairs could be made and this section could be reopened. Analysis indicated that very extensive repairs would be required, which the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) declined to make because of its $88 million cost, and the fact that this repair would make no material improvements to the highway's capacity and safety characteristics. Not long thereafter, the NYCDOT closed the West Side Highway from West 46th Street north to West 57th Street. Soon after the collapse of the elevated highway, a temporary roadway was hastily constructed along West Street and 12th Avenue. For a quarter-century after the collapse, this temporary highway served as the primary north-south highway on the West Side of Manhattan. Demolition of the elevated roadway, which began in 1977, would not be completed until 1989. In the intervening years, the abandoned roadway found multiple uses as a very popular running and bicycling path, as well as a staging area for concerts. From nycroads.com contributor Jeff Saltzman: The rotting hulk of the old highway was eventually torn down in stages, but the section stretching from the 40's to 57th Street lingered on for years. My friends and I took in many a pier concert from that highway. It was a great place to hang out and gave great views of the concerts below. Special thanks to http://www.nycroads.com |

|

|

THE BATTLE OVER WESTWAY:

In 1978, newly elected Mayor Ed Koch also changed his mind, joining Governor Carey in his support of the Westway superhighway and Westway State Park. In August 1981, just as the Army Corps of Engineers were granted a dredging and landfill permit, President Ronald Reagan joined in his support of Westway, ceremonially cutting an $85 million check to state and city officials. However, transportation officials and fiscal conservatives at the Federal level joined in a loose alliance with bureaucrats and environmentalists to undermine Westway. The bipartisan agreement was reported in The New York Times as follows: The agreement by the two Democratic leaders after ten years of wrangling between the city and state established the highway project as "the official policy" for the replacement of the West Side Highway between the Battery and West 42nd Street in Manhattan. The Westway is planned as a 4.2-mile roadway, sunken in some places and elevated in others, running along the Hudson River. It would be surrounded by 93 acres of parkland and 110 acres of landfill for future residential and commercial development. The cost would be more than $2.3 billion (in 1981 dollars). In 1982, Judge Thomas Griesa of U.S. District Court blocked the 1981 landfill permit, citing that the Corps of Engineers failed to assess the impact of the landfill on striped bass in the Hudson River. After three more years of delays and additional study, the Corps determined that at most, one-third of the striped bass in the Hudson would not survive the dredging and construction process. Still, Judge Griesa would not issue construction permits, citing that the evaluation procedures were inadequate. Governor Mario Cuomo, the third Governor to support Westway, vowed a swift repeal of the decision. However, after a 14-year battle, opposition forces finally gained victory. On September 30, 1985, New York City leaders decided to abandon Westway, allocating 60 percent of the approximately $1.7 billion in Federal Interstate funds to mass transit. The other 40 percent (about $690 million) of Federal funds, plus an additional state and city share of $121 million, was to be allocated to the "West Side Highway Replacement Project." This $811 million cap was to include the entire replacement facility from Battery Place north to West 59th Street. When the project was killed, The New York Times, historically a pro-highway voice during the Robert Moses era, had this to say about the demise of Westway: Why did a project offering so much to so many finally fall as flat as the old elevated West Side Highway it was to replace? The answer is horror of the automobile. |

|

|

notes |

London Terrace Tatler - January 1933 Pg 5 Mayor O'Brien Opens New Highway Inaugurates Extension of West Side Viaduct New York City formally opened the second section F, the new elevated highway running for Twenty-second to Thirty-eight Streets, with a dreary ceremony which represented also the first gesture of a public works nature for Mayor John P. O'Brien. This second section, erected at a cost of approximately $2,450,000, is a saga of steel girders in five minutes and thirty cents by the average taxi meter. A drive up its smooth concrete roads affords both an expansive view of the Hudson River and a technical education in steamship lines and wharves. For London Terrace residents the new extension, two minutes from the house, represents a savings of at least fifteen minutes, twenty-five cents by taxi, and a hazardous drive along Tenth Avenue. There was little fanfare at the opening ceremony. The exercises were opened with an introductory address by Commissioner Warren Hubbard, followed by an encomiastic talk by Borough President Samuel Levy and finally by a speech on economies by Mayor O'Brien. The three public officials then congratulated each other on the highway as a piece of construction, as a thing of beauty and as an economic joy. It was announced at that time that $10,000,000 was cut off the original $25,000,000 estimate for the cost of the entire highway. After the speeches, Mayor O'Brien cut the white tae with his little gold scissors and the highway was formally opened, wile the band of the Department of Public Works, dressed in festive blue and white, blew clarions and the steamboats on the river hooted their solemn approval. "I am glad to be here," Mayor O'Brien shouted into the microphone, some of his remarks drowned by noises from the river, "because somehow with the theme of economy turning in the minds of public officials and with the watchword of economy and efficiency before us, we have the opportunity to see symbolized those very principles that mean so much to the city; especially the economy part of it -- notable in the $10,000,000 savings on this project, together with economy in time of erection and economy of inconvenience." He linked his arm with Borough President Levy. "As Mayor of the City of New York," he punned. "I now officially open the second section of this express highway and express the hope that the whole projected highway will soon be consummated." The ceremony was closed with a parade of official cars up the new extension to Thirty-eight Street. Mayor O'Brien leading the procession in his limousine. |