The Hippodrome Theatre stood in New York City from 1905 to 1939, on the

site of a what is now a large modern office building known as "The

Hippodrome Center", at 1120 Avenue of the Americas, in the Theater

District of Midtown Manhattan. It was called the world's largest theatre

by its builders.

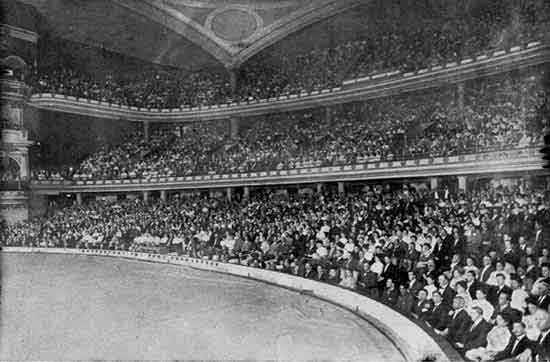

The Hippodrome was built by Frederick Thompson and Elmer Dundy, creators

of the Luna Park amusement park at Coney Island. The theatre was located

on Sixth Avenue, now named Avenue of the Americas, between Forty-third

and Forty-fourth streets. Its auditorium seated 5,300 people and it was

equipped with what was then the state of the art in theatrical

technology. The theatre was acquired by The Shubert Organization in

1909.

Construction

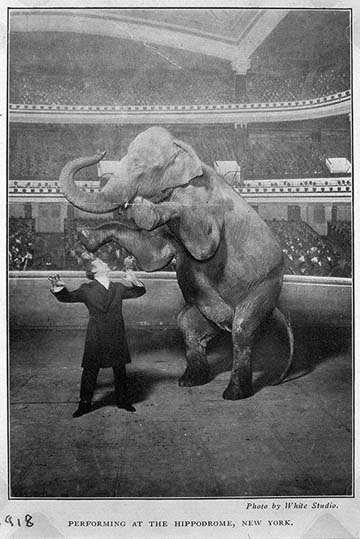

With J. H. Morgan as architect, the Hippodrome first opened in 1905 with

a seating capacity of 5,200, and is still considered as one of the true

wonders of theatre architecture. Its stage was 12 times larger than any

Broadway "legit" house and capable of holding as many as 1,000

performers at a time, or a full-sized circus with elephants and horses.

It also had an 8,000-gallon clear glass water tank that could be raised

from below the stage by hydraulic pistons for swimming-and-diving shows.

The glory years

For a time the Hippodrome was the largest and most successful theater in

New York. The Hippodrome featured lavish spectacles complete with circus

animals, diving horses, opulent sets, and 500-member choruses. Until the

end of World War I, the Hippodrome housed all sorts of spectacles then

switched to musical extravaganzas produced by Charles Dillingham,

including "Better Times," which ran for more than 400 performances.

When Dillingham left in 1923 to pursue other interests, the Hippodrome

was leased to Keith-Albee, which hired Thomas Lamb to turn it into a

vaudeville theatre by building a much smaller stage and discarding all

of its unique features. The most popular vaudeville artists of the day,

including illusionist Harry Houdini, performed at the Hippodrome during

its heyday. Others might vanish rabbits, but in 1918, on the

brightly-lit stage of the Hippodrome, Houdini made a 10,000-pound

elephant disappear. He created a sensation. When Houdini fired a pistol,

Jennie vanished from view.

The Hippodrome's huge running costs made it a perennial financial

failure, and a series of producers tried and failed to make money from

the theatre. It became a location for vaudeville productions in 1923

before being leased for budget opera performances, finally becoming a

sports arena.

Decline and fall

In 1922, the elephants that graced the stage of the Hippodrome since its

opening moved uptown to the Bronx's Royal Theater. On arrival, stage

worker Miller Renard recalled, the elephants were greeted with

extraordinary fanfare:

The next day the Borough President gives them a dinner on the lawn of

the Chamber of Commerce up on Tremont Avenue, with special dinner menus

for the elephants. It was some show to see all those elephants march up

those steps to the table where each elephant had a bail of hay. The[n],

the Borough President welcomes the elephants to the Bronx, and the place

is just mobbed with people. And that was the worst week's business we

ever done in that theatre.

In 1925, movies were added to the vaudeville, but within a few years,

competition from the newer and more sumptuous movie palaces in the

Broadway-Times Square area forced Keith-Albee-Orpheum, which was merged

into RKO by May 1928, to sell the theatre. Several attempts to use the

Hippodrome for plays and operas failed, and it remained dark until 1935,

when producer Billy Rose leased it for his spectacular Rodgers & Hart

circus musical, Jumbo, which received favorable reviews but lasted only

five months due to the Great Depression.

After that, the Hippodrome sputtered through bookings of late-run

movies, boxing, wrestling, and Jai Lai games before being demolished in

1939 as the value of real estate on Sixth Avenue began to escalate. The

New York Hippodrome closed on August 16, 1939. Unfortunately, the start

of World War II delayed re-development, and the Hippodrome site remained

vacant until 1952, when it was taken over for a combination office

building and parking garage.

Chronological Program List

March 26, 1907, Double billing of "Neptune's Daughter" (opera) and

"Pioneer Days" (drama). In between the two performances, a variety of

circus acts entertained.[1]

Legacy

The building was torn down in 1939, though an office building and

parking garage that today stands on the same site claims the name "The

Hippodrome Center." [2] Through the 1960s the modern building was the

corporate headquarters of the old Charter Communications Inc. media

publishing company.

In the 1970s the famous old theater also gave its name to the nearby

"Little Hippodrome", a drag and comedy club which was located at 227

East 56th Street, between Second and Third Avenues. The club is famous

for hosting the final live New York performances of the legendary Glam

rock group, The New York Dolls in March 1975, a month before the group

disbanded. [3] The show recorded at that venue appeared later as the

group's Red Patent Leather album. [4] Soon after in 1975 that location

of the defunct Little Hippodrome club re-opened as The East Side Club, a

gay men's social club. [5]

The largest theater in New York City is now Radio City Music Hall.

References

^ Theatre record and scrap book, 1904-1908. Clarke Historical Library

(located inside Park Library, CMU campus) manuscript. Mt. Pleasant, MI

^ The Hippodrome Center, Star Office Space

^ From the Hip, "It's All the streets you crossed not so long ago" blog,

October 18, 2005, from Nina Antonia, "Too Much, Too Soon" London:

Omnibus, 1998, and Village Voice ad, March 30, 1975

^ Live in NYC - 1975, mp3.com

^ East Side Club home

Kenneth Jackson (1995). Encyclopedia of New York City. Yale University

Press. ISBN 0-300-05536-6.

|

|

With J. H. Morgan as architect, the

Hippodrome first opened in 1905 and is still considered as one of the

true wonders of theatre architecture. Its stage was 12 times larger than

any Broadway "legit" house and capable of holding as many as 1,000

performers at a time, or a full-sized circus with elephants and horses.

It also had an 8,000-gallon clear glass water tank that could be raised

from below the stage by hydraulic pistons for swimming-and-diving shows.

Until the end of WWI, the Hippodrome housed all sorts of spectacles,

then switched to musical extravaganzas produced by Charles Dillingham,

including "Better Times," which ran for more than 400 performances. When

Dillingham left in 1923 to pursue other interests, the Hippodrome was

leased to Keith-Albee, which hired Thomas Lamb to turn it into a

vaudeville theatre by building a much smaller stage and discarding all

of its unique features. In 1925, movies were added to the vaudeville,

but within a few years, competition from the newer and more sumptuous

movie palaces in the Broadway-Times Square area forced Keith-Albee, by

then merged into RKO, to sell the theatre. Several attempts to use the

Hippodrome for plays and operas failed, and it remained dark until 1935,

when producer Billy Rose leased it for his spectacular Rodgers & Hart

circus musical, "Jumbo," which received favorable reviews but lasted

only five months due to Depression conditions. After that, the

Hippodrome sputtered through bookings of late-run movies, boxing,

wrestling, and jai lai games before being demolished in 1939 as the

value of real estate on Sixth Avenue began to escalate. Unfortunately,

the start of WWII delayed re-development, and the Hippodrome site

remained vacant until 1952, when it was taken over for a combination

office building and parking garage.

The New York Hippodrome

One year following the opening of Luna Park, Thompson & Dundy made a

small step and a giant leap towards Manhattan. In 1905 the Hippodrome on

Sixth Avenue between 43rd and 44th street is built, only one block away

from the newly named Times Square. With it, the entrepreneurs radically

changed the world of Times Square in two ways. First, its low admission

prices were aimed at the middle class, who had thus far been unable to

visit the costly legitimate Broadway theatres. Second, it brought the

high-tech pleasures of the amusement parks to the inner city. The

combination of these two factors made the Hippodrome what Thompson

called a "gigantic toy" for the masses. "The toymaker of New York", as

he had proclaimed himself, however, had designed it not for children,

but for the adult consumer.6 In Thompson's opinion, the

turn-of-the-century American adult suffered from too much work and too

little play. He had first created the enlarged playground that allowed

them to return to their childhoods. As was the purpose of Luna Park, the

fantastic shows at the Hippodrome would temporarily offer an escape for

its visitors away from their grim world.

The idea of building a hippodrome in New York City was not entirely new.

Circus-director P.T. Barnum had built the Roman hippodrome between 26th

and 27th streets in Manhattan. Its many imported spectacles were closely

related to the circus, such as chariot races and Wild West violence. But

even Barnum's 8000-seat circus paled in comparison with the proposal

made by Steele Macay for the Spectatorium. The 10,000-seat Spectatorium

was to be built as a permanent theatre for the Columbian exposition in

Chicago in 1893. Macay's ideals closely resembled those of Frederic

Thompson; he dreamt of "subsidizing the genius of the whole world, for

the education and inspiration of the masses, while affording them, at

moderate prices, and entertainment as irresistibly fascinating as it was

ennobling."7 The Spectatorium, however, was never completed, after

investors had been frightened away by a stock market collapse known as

the Panic of 1893. It is very likely that Thompson, while working at the

Columbian exposition, became aware of Macay's plans and subsequently

inspired by his ideas.

In 1901 Thompson moved to New York following the Pan-American exposition.

Disappointed by the entertainment the city had to offer to the abundant

middle-class audience, Thompson & Dundy tried to put a hippodrome at

39th street and 7th Avenue, but were thwarted by opposing neighborhood

residents. For the time being, they concentrated on Coney Island.8

Following the success of Luna Park, the two had little trouble finding

investors for the Hippodrome. The profits made from Luna Park had been

substantial, but not nearly enough to finance the price of the

Hippodrome, the property, and its stage entertainment, which Thompson &

Dundy advertised as $3,500,000. Together, they were able to convince a

number of powerful businessmen and financiers, not impresarios or

showmen, of the viability of their unique formula of amusement as a

money-making investment.

Construction of the Hippodrome was completed in 10 months, another

record-breaking achievement, made possible by the fact that the

construction company was owned by one of the financial backers. When

construction had begun, residents of the area expressed their

disapproval of the project, which had come to them as a great surprise.

The Theatre Syndicate, who held a near monopoly on theatrical

productions in the US, allegedly tried to delay the Hippodrome's

construction through the city Building Department.

Nonetheless, the 5200-seat Hippodrome opened April 12, 1905 performing two

double-feature shows six days a week. 9

Department store theatre (democratizing theatre)

The concept of the Hippodrome was also inspired by the fairly new

department store, which had begun to increasingly dominate the face of

urban retailing at the turn of the century. These enormous stores,

offering a lavish amount of different goods attracted millions of

consumers, and promoted shopping as an important and entertaining

activity. Their innovative advertising and merchandising schemes were

particularly aimed at middle-class women. The stores offered various

free services available to all customers regardless of their ability to

buy. Thus, shopping had been democratized; the city's wealthiest and

humblest walked the same aisles even if they could not buy the same

products. "We are coming to the age of the department store in

theatricals," Thompson stated in 1904. "The masses are ready to welcome

it."10

The Hippodrome had, according to Thompson, democratized theatre-going in

the same way that department stores had democratized shopping. Like in

the department stores, the wealthy and the humble were able to

experience together the same abundance of pleasures.11 The masses

themselves, however, were an important part of the experience. A smaller

theatre-house with a more expensive admission price may well have been

able to collect the same amount of money, but would lack the grandeur of

a hippodrome. Consequently, the Hippodrome demanded packed houses to

afford to present its high-tech theatrical extravaganza.

Oscar Hammerstein, a producer of numerous shows and builder of "the

grandest amusement temple in the world," the Olympia, back in 1895,

predicted that "The theatres will suffer immensely...for at least the

first six weeks." and "The enormous crowds that will naturally be

attracted to the novelty of this establishment must come from somewhere,

and they will be drawn from the regular theatres." Others predicted an

overall decline in theatre ticket prices, and the Theatre Syndicate

subsequently brought their prices down to one dollar.12

The Hippodrome's amusement, however, did not only challenge the elite

entertainment, but also the popular Barnum & Bailey circus. Thompson &

Dundy had raided several circuses for arena acts, including the Barnum &

Bailey and the Ringling Brothers Circuses. Barnum & Bailey arranged a

non-competition agreement with Ringling Bros., in exchange for which

Ringling broke its agreement to provide further acts for the Hippodrome.

Thompson & Dundy boasted that they had obtained all the billboard space

available in New York. The Barnum & Bailey Circus struck back in 1905 by

announcing it would begin the longest circus season in New York's

history.13

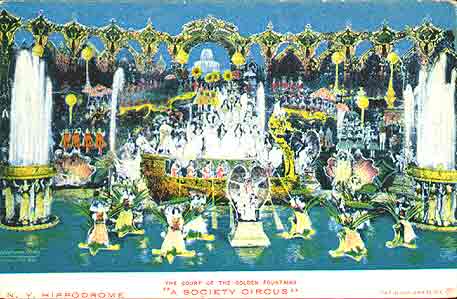

Thompson & Dundy had collected the greatest talents in choreography,

costume and stage design, writers and composers from around the world

for their gargantuan opening shows. The shows A Yankee Circus on Mars

and A Society Circus were eclectic spectacles combining vaudeville,

pantomime, circus and popular songs with technological novelties.

Electricity was used in every conceivable way in the Hippodrome, from the

obvious to the inventive. The entire block-long facade was itself an

electrical billboard, that "threw a fire and glare of electric

illumination for miles." When approaching the theatre, "a tumult of

sudden light hit you on the eyeballs ... you couldn't possibly pass it

by unnoticed."14 The Hippodrome threw the spark that would forever light

Times Square. The inside of the theatre was as much an unequalled

lighting spectacle. The amount of current used by the Hippodrome's stage

was more than the average electrical station could supply. Electricity

also warmed the grease paint and curling irons for hundreds of chorus

girls; wardrobes used electric irons to press costumes; carpenters

heated their glue with electricity; chefs used electric ovens and

dishwashers; the building itself was supplied with an electrified

heating and cooling system, water pumps, telephones, hydraulic elevators

and mechanical hoists, and numerous other electrical conveniences.15

In 1906, Thompson & Dundy lost their creation to their financial backers.

Shocked by an unexpected decline in attendance during the Hippodrome's

second season, the investors battled with the producers to raise ticket

prices. Furthermore, the investors were concerned by Thompson's plans

for an amusement park in Manhattan, which they viewed as a competitor of

the Hippodrome. Thompson & Dundy joined the Theatre Syndicate that same

year, and continued to produce theatre shows together, until Dundy's

untimely death in 1907. In the latter half of the century, an office

tower was placed on the site of the Hippodrome; only the name remains in

silver-colored lettering on the modernist facade.

NOTES

6. "Gigantic toy" quotation comes "Opening of Hippodrome," New York

Tribune (April 13, 1905); "New York's Gigantic Toy," p.243-244 7. Percy

MacKaye, Epoch; The Life of Steele MacKaye, Genius of the theatre, New

York 1927; "New York's Gigantic Toy," p.245 8. "New York's Gigantic

Toy," p.245-248 describe Thompson's pre-Luna life. More about Thompson's

Peter Pan-like character is described on p.266-270. 9. "New York's

Gigantic Toy," p.250-253 10. " ‘Big Store' Idea to Give Masses

Entertainment," New York Morning Telegraph (September 26, 1904); "New

York's Gigantic Toy," p.248 11. "New York's Gigantic Toy," p.248-249 12.

Vincent Sheean, Oscar Hammerstein I: The Life and Exploits of an

Impresario, New York 1956; "New York's Gigantic Toy," p.250-251. 13.

"New York's Gigantic Toy," p.251 14. untitled article by Alan Dale (ca.

April 13, 1905); "New York's Gigantic Toy," p.257 15. A close

description with photographs of the Hippodrome lighting apparatus and

other uses of electricity appear in "Electricity at the New York

Hippodrome," Electrical World 47 (May 5, 1906) p.911-916, and "The

Illumination of the New York Hippodrome," Illuminating Engineer 1 (April

1906), p.72-77; "New York's Gigantic Toy," p.257-258 ; IMAGES: The New

York Hippodrome, postcard c. 1905; Cover detail of "Souvenir Book of the

New York Hippodrome," The Theatre Collection, Museum of the City of New

York; Inventing Times Square

Thanks to http://home.luna.nl

New York City's Hippodrome Closed Its

Doors for the Last Time

August 16, 1939

Would you like to watch Harry Houdini, legendary magician and escape

artist, make an elephant disappear right in front of your eyes? Or watch

diving horses while a 500-member chorus sings in triumph? Or see some of

your favorite comedians and singers perform live on a huge sparkling

stage? Back in the 1920s, you could have seen all this at New York

City's famous Hippodrome Theater. But on August 16, 1939, the Hippodrome

closed its doors for the last time.

Built in 1905 with a seating capacity of 5,200 people, the Hippodrome was

at one time the largest and most successful theater in New York. It

featured lavish spectacles complete with circus animals, diving horses,

opulent sets, and 500-member choruses. The most popular vaudeville

(variety stage) artists of the day, including Harry Houdini, performed

at the Hippodrome during its heyday. But by the late 1920s, the growing

popularity of motion pictures replaced the vaudeville acts and circus

spectacles presented at the Hippodrome.

In 1928, RKO, the motion picture company, purchased the theater. Movie

screens took over the stages for audiences who were hungry for this new

kind of entertainment. After it closed its doors in 1939, the Hippodrome

Theater presented its final spectacle: the building's demolition. The

era that made the Hippodrome famous lives on in the American memory. Do

you know the names of any other stars from that vaudeville era? Ask a

grandparent!

|