|

New York

Architecture Images- Gone Charles M. Schwab mansion |

|

architect |

Maurice Hebert |

|

location |

the entire block between West End Avenue and the Riverside Drive, Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth streets |

|

date |

1901 |

|

style |

Chateauesque |

|

construction |

limestone |

|

type |

House |

|

images |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

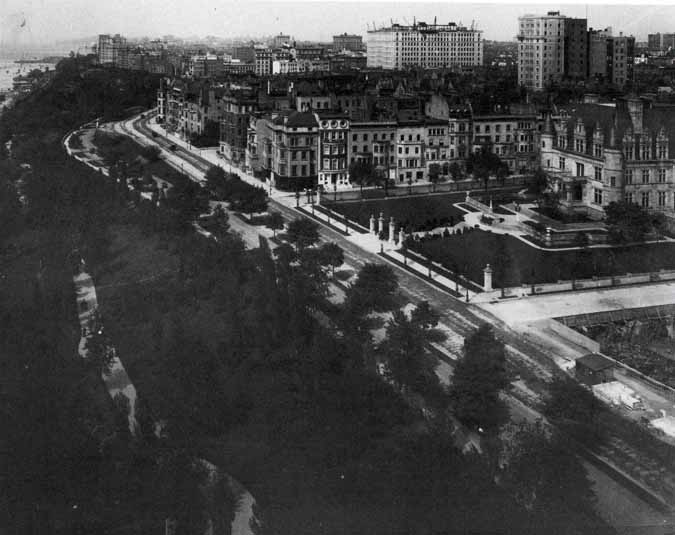

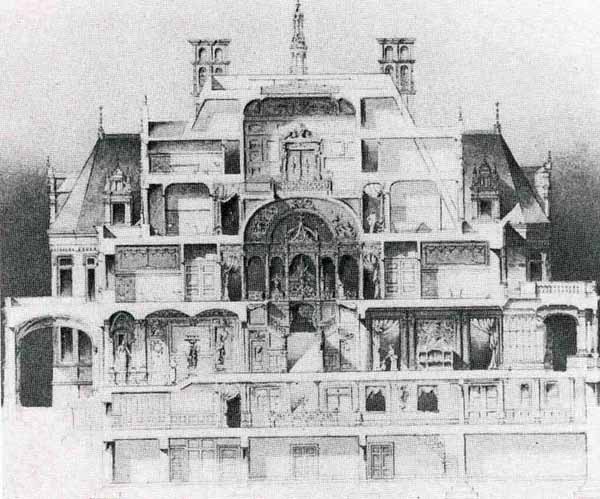

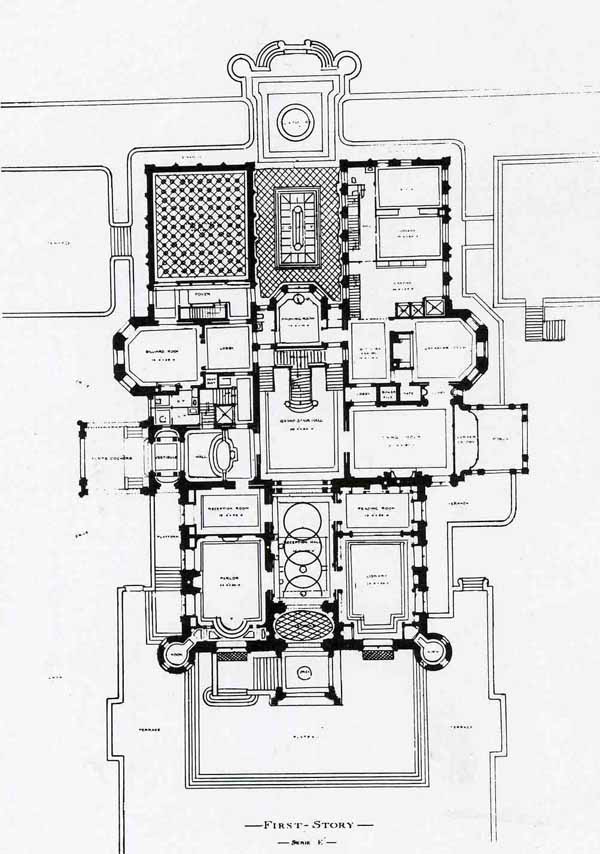

The Charles M. Schwab mansion was the most

lavish of the turn-of-the-century villas on Riverside Drive. He was so

intent on rivaling Andrew Carnegie, his partner in the United States

Steel Corporation, Schwab purchased the site of the Orphan Asylum

Society encompassing the entire block between West End Avenue and the

Drive, Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth streets, for $865,000, an

unprecedented sum for a building lot in 1901. Construction began in 1901

and lasted six years. The French architect Maurice Hebert designed a French Renaissance chateau set in its own landscaped park. The Riverside Drive facade was based on that of Chenon ceaux. The rear was a more relaxed composition based on fragments of the chateaux at Blois and Azay-le-Rideau; the rather coldly archaeological feeling of the river facade was somewhat alleviated by the use of brick with stone trim and variegated massing. Inside, a broad two-and-a-half-story hall surrounded by balconies led to a monumental staircase lit from above, creating an effect less like that of a house than of a public building. Provisions for servicing the owner's needs were unprecedented in their complexity and included garages for four cars, a separate receiving lodge for goods, and a service tunnel buried beneath the garden terraces. A belfry with chimes, indoor swimming pool, chapel and roof garden served less practical functions. Hebert's design of the Schwab house was criticized by the Architectural Record as literal, heavy-handed and distinctly less effective than Haight's more "intelligent and effective adaptation" of similar motifs at the Cancer Hospital a decade before."' Nonetheless the house was admired as a type, and Schwab regarded as a "pioneer in detecting the true uses of the West Side.... Riverside Drive, from the moment of its completion, seemed plainly destined to be a boulevard of palaces, a rus in urbe combining the great prospect, down, up, across the Hudson, with easy accessibility from the commercial quarters and from stage-land and clubland. Suburban [the houses] should have been, in the sense of being detached and lighted all around. The removal of the orphanage from the Schwab site sparked a renaissance of building in the side streets off the Drive just above Seventy-second Street, creating a Classical enclave at the southern end of the Drive which balanced the development around 106th Street, near its northern end. Babb, Cook & Willard's townhouses for Mrs. J.0. Hoyt and E.J. Stimson (1897) at 310-312 West Seventy-fifth Street were unusual in that, though similar in design, they were executed in different materials. The Stimson house had a narrow entrance court at its western flank allowing the principal rooms greater privacy and ventilation. The facades were suave, delicate essays in French Baroque. Herts & Tallant's 1904 remodelling of an 1887 townhouse facade by E.L. Angell at 232 West End Avenue, between Seventieth and Seventy-first streets, was a gran diloquent example of the Modern French style. A broad segmental arch sheltered an outdoor vestibule, creating a theatrical entrance and disguising the off-center position of the doorway in Angell's English basement plan. The floors above were united in a two-story glazed bay set within a rusticated frame, further exaggerating the scale of the house. While the work of Janes & Leo dominated the upper West End, C.P.H. Gilbert's early career flowered at its southern end. His house (ca. 1899) at Seventy-second Street and Riverside Drive revealed the deft synthesis of Classical massing and plan with late French Gothic and early Renaissance detailing which was his trademark.3ss This was also evident in his 1894-95 design for 330 West Seventy-sixth Street, between West End Avenue and Riverside Drive.3ss Here the combination of delicate stone carving and buffcolored Roman brick lent the house a warmer texture than characterized Gilbert's later stone work on the East Side. The houses of Mrs. Miller and Mrs. McGucken at 307-309 West Seventy-sixth Street were exceptions to the Fran;ois I mode that dominated Gilbert's career.3s' Perhaps in order to relate to the adjacent Lamb & Rich houses, their red and brown brick facades were delicate, low-relief abstractions of Classical motifs, with iron brackets supporting a deeply projecting wooden cornice. The fashionable set's most public monument since it opened in 1890, but it was doomed by Prohibition as well as the northward migration of the entertainment district; the last major function held there was the infamously stalemated 1924 Democratic National Convention. Stanford White's New York Herald Building, built in 1894, when its location at Thirty-fifth Street and Broadway was considered well uptown, had become engulfed by the city's most populous shopping district, and in 1921 it too met the wrecker's ball. 2$ But the most symbolic of the losses were the two Vanderbilt houses. The first to go was the house Richard Morris Hunt had designed in 1880 for William K. Vanderbilt at Fifty-second Street and Fifth Avenue.29 Its passing in 1924 marked not only the end of the era of great mansions but also the transformation of the blocks of Fifth Avenue below Central Park into a densely built-up stretch of offices and shops. A little more than a year later, George Post's house for Cornelius Vanderbilt II suffered the same fate, although its replacement, the block of shops designed by Buchman & Kahn and principally occupied by Bergdorf Goodman, at least approached the social, if not the compositional, elegance of its predecessor. But despite the latter house's elegant replacement, the demolition of the two mansions, as well as the contemporaneous destruction of mansions belonging to William Astor and C. P. Huntington, reflected radical changes not only in the city's architectural and urbanistic texture, but also in its social composition. As the editors of Vanity Fair snobbishly reported in 1925, the grand piles had "at last been resold to speculators and traders who only ten years ago boasted of no fortunes at all. . . . To old New Yorkers, the real melancholy comes, not from the fact that the houses are soon to crumble into dust, but that the old and well ordered social fabric ... has itself crumbled and vanished utterly from view. In place of a society restricted to a few hundred people of good breeding, we now have a social fabric mounting into the thousands, most of whom have inherited no very traditional creed of conduct or behavior. " As the era wore on, nearly all of the city's wealthiest residents abandoned their palatial Manhattan townhouses in favor of country houses supplemented by less grandiose city apartments, motivated, as the New York Times reported, by "steep land valuations and taxes, the passion for country life, the avoidance of noise [and] the care of administration." The destruction of Stanford White's 1885 house for Charles Tiffany in 1936 constituted the passing of one of the city's most important monuments. Its loss was, according to Henry Saylor, accompanied by not so much as "a murmur of regret on the part of the public or the press. We do seem to be able to muster some respect for monuments of real antiquity in this country, but give the younger relics short shrift. Charles Schwab's decision in 1939 to close his French Renaissance style chateau on Riverside Drive between Seventy-third and Seventy-fourth streets was one of the last nails in the coffin of a lavish domestic metropolitanism. Though only thirty-two years old, the Schwab house seemed preposterously anachronistic. As the New York Times understatedly editorialized, it had come "to have a sort of antiquity. Before the mansion was destroyed, its transformation into the official mayoral residence was considered but rejected after Mayor La Guardia, reflecting the new era's tastes and values in his characteristically feisty manner, reputedly stated, "What! Me in that!" The previous generation's palatial apartment buildings also fell victim to changing times. In 1936 the last tenant moved out of the splendid Alwyn Court apartment houses at Seventh Avenue and Fifty-eighth Street, and after twentyeight years of service as a monument to luxury, the building was boarded up. 35 Two years later, the Dry Dock Savings Institution, which held the mortgage, undertook, with its architect Louis S. Weeks, to demolish the interior of the building completely, replacing the original twenty-two apartments, which ranged from fourteen to thirty-four rooms in size, with seventy-five three-, four-, and five-room suites; apartments also replaced janitors' rooftop storage sheds, and the building's elegant corner entrance was relocated to Seventh Avenue in order to give better access to its new elevators. Only the remarkable exterior ornamentation was left to remind tenants and passersby of a more extravagant and gracious era. The destruction of such landmarks reflected not only changes in public taste and the fluctuations of the real-estate market, but profound changes in prevailing architectural attitudes as well. The comfortable stylistic consensus of the Composite Era had dissolved, to be replaced by a bewildering array of new directions. In the Composite Era architects had escaped into historicism as a refuge from the materialism of modern society. In a city populated with recent immigrants, without its own traditions, closely knit social fabric, or identifiable culture, architects had drawn on the full panoply of Western architectural history to create the heroic fiction of a well-ordered, stable society. Literal historicism offered the most accessible vocabulary of ready-made symbols; thus, when the Vanderbilts built themselves a Fifth Avenue chateau, anyone, educated or not, could understand what role the family envisioned playing in society. The historicism of the Composite Era had taken two major avenues of expression: Scientific Eclecticism and the socalled Modern French style. The first, epitomized by the work of McKim, Mead & White, involved a fairly literal replication of details or even entire compositions from the past. It was not limited to any particular style; instead the Scientific Eclectics valued scholarship and treasured the literary associations attached to each era-whether the imperial grandeur of High Roman Classicism, the humanism and enlightened commercialism of the Florentine Renaissance, or the sobriety of English Georgian. While this form of expression was aimed at providing the city-dweller with the sense of a noble past, the Modern French school, on the other hand, offered the more forward-looking reassurance that the present was a continuation of, or even an improvement upon-but definitely not a revival of-the past. In effect, the Modern French style was part of a wider trend best described as Modern Classicism. Represented by architects such as Carrere & Hastings and Ernest Flagg, whose often overblown and baroque version of the style was distinctly French, or by Robert Kohn, whose Classicism was really inspired by Austrian and German models, the style ranged from the deeply cut rustication, bulbous mansard roofs, overscaled consoles, and overripe garlands of the "cartouche architecture" of fin-de-siecle Paris to the considerable delicacy and elegance of a synthetic Modern Renaissance. More important, its inherent modernity encouraged architects to employ new technologies and to explore new building types, in, most notably, such examples as Warren & Wetmore's Grand Central Terminal and Flagg's office buildings. |

|

|

|

|

Charles Michael Schwab (February 18, 1862 in Williamsburg, Pennsylvania -

October 18, 1939 in London, England) was an American industrialist who

became a multimillionaire in the steel industry but died bankrupt. Schwab was born into a German Catholic family in Williamsburg, Pennsylvania and grew up in Loretto, Pennsylvania, which he would always consider his "home town". He attended Saint Francis College, now Saint Francis University, but left after two years to find work in Pittsburgh. He started as a stake driver in Andrew Carnegie's steelworks and in 1897 rose to become president of the Carnegie Steel Company at the age of 35. In 1901, he negotiated the secret buyout of Carnegie Steel to a group of New York-based financiers led by J.P. Morgan. After the buyout, Schwab became the first president of the U.S. Steel Corporation, the company formed out of Carnegie's former holdings. However Schwab found U.S. Steel to be unwieldy and inefficient. After several clashes with Morgan and company executive Elbert Gary, he resigned in 1903. He left the company to run the Bethlehem Steel Company, which under his direction became the largest independent steel producer in the field. Part of Bethlehem Steel's success was the development of the H-beam, a precursor of today's ubiquitous I-beam. Charlie Schwab was interested in producing such a wideflange steel beam, a risky venture that required capitalization and new plant construction to make an unproven product. "I've thought the whole thing over," Schwab told his secretary, "and if we are going bust, we will go bust big." It is his most famous remark. In 1908, Bethlehem Steel began producing the beam, which revolutionized building construction and made possible the age of the skyscraper. Its success helped make Bethlehem Steel the second-largest steel company in the world. Bethlehem, Pennsylvania was incorporated, virtually as a company town, by uniting four previous villages. In 1910, Schwab broke the Bethlehem Steel strike by calling out the newly-formed Pennsylvania State Police. Schwab kept labor unions out of Bethlehem Steel, which was not organized until 1941, two years after his death. Schwab eventually moved to New York City, specifically the Upper West Side, which at the time was considered the "wrong" side of Central Park, and where he built "Riverside", the most ambitious private house ever built in New York. The US$7 million 75 room house combined details from three French chateaux on a full city block. After Schwab's death, New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia turned down a proposal to make the mansion the official mayoral residence, considering it to be too grandiose. It was eventually torn down and replaced by a drab apartment block. He also owned a 44 room summer estate on 1,000 acres (4 km²) in Loretto called "Immergrün" (German for "evergreen"). The house featured opulent gardens and a nine hole golf course. Rather than tear down the existing house, Schwab had the mansion raised on rollers and moved 200 feet to a new location to make room for the new mansion. Schwab's estate sold Immergrün after his death and it is now Mount Assisi Friary on the grounds of Saint Francis University. Schwab was considered to be a risk taker and was highly controversial. He circumvented American neutrality laws during the early years of World War I by funneling goods through Canada. After America's entry into the war, he was accused of profiteering but was later acquitted. His lucrative contract providing steel to the Trans-Siberian Railroad came after he provided a US$200,000 "gift" to the mistress of the Grand Duke Alexis Aleksandrovich. Thomas Edison once famously called him the "master hustler". Schwab was notorious for his "fast lane" lifestyle including opulent parties, high stakes gambling, and a string of extramarital affairs producing at least one illegitimate child. He became an international celebrity when he "broke the bank" at Monte Carlo and traveled in a US$100,000 private rail car named "Loretto".[1] Even before the Great Depression, he had already spent most of his fortune estimated at between $25 million and US$40 million. Adjusted for inflation, that equates to between $275 million and US$440 million in modern terms. The affairs and the illegitimate child soured his relationship with his wife. The stock market crash of 1929 finished off what years of wanton spending had started. He spent his last years in a small apartment. He could no longer afford the taxes on "Riverside" and it was seized by creditors. He had offered to sell the mansion at a huge loss but there were no takers. At his death ten years later, his holdings in Bethlehem Steel were virtually worthless due to the company's bankruptcy. He was over US$ 300,000 in debt. Had he lived a few more years, he probably would have seen his fortunes restored when Bethlehem Steel was flooded with orders for war material. He was buried in Loretto. A fine bust-length portrait of Schwab painted in 1903 by the Swiss-born American artist Adolfo Müller-Ury (1862-1947) was formerly in the Jessica Dragonette Collection at the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming at Laramie, but has recently been donated to the American National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC. Müller-Ury also painted his nephew as a boy in a sailor-suit around the same date. He was not related to Charles R. Schwab, founder of the Charles Schwab Corporation. However, according to John Rothchild's The Bear Book - Survive and Profit in Ferocious Markets, this Charles Schwab is the grandfather of Charles R. Schwab the discount broker. References Hessen, Robert, Steel titan: the life of Charles M. Schwab, Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press (1990). James H. Bridge, The Inside History of the Carnegie Steel Company (1903) Ida M. Tarbell, The Life of Elbert H. Gary (1925) Arundel Cotter, The Story of Bethlehem Steel (1916) and United States Steel: A Corporation with a Soul (1921) Burton J. Hendrick, The Life of Andrew Carnegie (2 vols., 1932; new introduction, 1969) Stewart H. Holbrook, Age of the Moguls (1953) Joseph Frazier Wall, Andrew Carnegie (1970) and Louis M. Hacker, The World of Andrew Carnegie (1968). Burton W. Folsom, Jr., The Myth of the Robber Barons, Young America. Hill, Napoleon, Think and Grow Rich (1937) ^ North Carolina Transportation Museum: Rail Equipment1 John Rothchild, The Bear Book - Survive and Profit in Ferocious Markets (1998). P.250 |

|