|

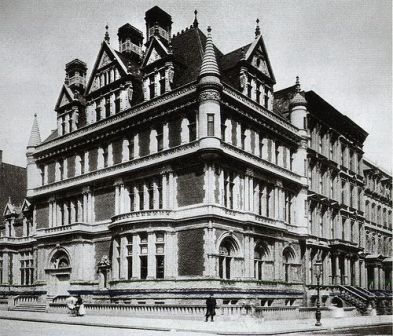

William Vanderbilt’s Petit Chateau by Richard Morris

Hunt was demolished in 1962 to make way for the store.

Photograph from the Bergdorf Goodman Archives, 1920s.

-------------------

Not to be Outdone -- Cornelius Vanderbilt's 1893 Chateau

When the founder of the Vanderbilt dynasty, Cornelius “Commodore”

Vanderbilt, died in 1877 he left his favorite grandson and namesake,

Cornelius Vanderbilt II, a $5 million inheritance. The following year

Vanderbilt purchased and demolished three brownstone houses on the south

west corner of 57th Street and 5th Avenue in preparation for his new

mansion.

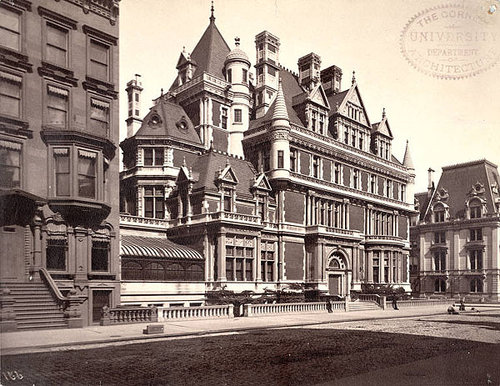

Vanderbilt commissioned George Brown Post to design his grand home. In a

vast departure from the brownstone tradition of 5th Avenue, Post created

a red brick and limestone chateau brimming over with turrets and

dormers, deeply arched windows and highly ornate chimneys.

The original 57th Street Mansion -- NYPL Collection

The interiors were decorated by a team of artisans, among them the most

esteemed names of the time: John LaFarge, Augustus Saint-Gaudens and his

brother Julius, Frederick Kaldenberg, Philip Martiny, Rene de Quelin and

Frederick W. MacMonnies. Alice Vanderbilt was acutely aware that the old

New York society families with names like Schuyler and Van Rensselaer

considered her family nouveau riche and therefore wanted a Vanderbilt

coat of arms to be emblazoned in the entry hall for all to see. After

months of research and finding no hereditary coat of arms, she simply

made one up -- and a crest to go with it.

Both were included in Saint-Gaudens magnificent 11 by 15 foot entry hall

mantelpiece which included two ruddy-colored marble caryatids

representing Pax and Amor supporting the mantel. The mosaic overmantle

depicts a classical maiden with the inscription in Latin composed by

Vanderbilt himself: The house at its threshold gives evidence of the

master’s good will. Welcome to the guest who arrives. Farewell and

helpfulness to him who departs.”

For the 45-foot dining room Saint-Gaudens also sculpted wooden relief

portraits including, according to the artist “…the young Cornelius and

George Vanderbilt, Gertrude Vanderbilt, now Mrs. Harry Payne Whitney,

William H. Vanderbilt, and Cornelius Vanderbilt, the first of the

family.” Here the lower walls were paneled in oak, the upper portions

covered in embossed, brown leather. A coffered ceiling hung overhead

which Saint-Gaudens termed “superb.” It consisted of twenty panels, six

of which were opalescent and “jewel” glass skylights by John LaFarge.

The beams were inlaid with mother of pearl in a Greek key pattern. Green

marble reliefs of Hospitalitas and Amicitia flanked the doorway, their

faces, clothing and other details executed in ivory, iridescent metals

and mother of pearl.

Eight years later, upon the death of his father William Henry,

Vanderbilt inherited another $67 million, adding to the fortune he was

already amassing as chairman of the family railroad empire. By the

beginning of the 1890s, other millionaires were building larger and more

lavish palaces along Fifth Avenue, a trend that Vanderbilt took as a

personal threat to his family’s social station. He decided to extend his

mansion, building something so large and so extravagant that no one

could surpass it.

Vanderbilt purchased and destroyed five “costly” brownstone houses

abutting his property to the north, facing 58th Street. Once again he

called on George Post, along with mansion designer Richard Morris Hunt

as consultant. Ground was broken on March 1, 1892 and all of New York

watched in anticipation as the work proceeded. Because Vanderbilt wanted

his home finished as quickly as possible – giving the builder, David H.

King, Jr., 18 months to complete it – 600 workmen were employed,

sometimes working around the clock “under powerful electric lights.”

Thousands of people watched the construction for a year and a half with

what The New York Times called “pardonable curiosity and instinctive

local pride.”

On November 26, 1893 The Times excitedly reported on the near-completion

of the mansion. Calling it “the finest private residence in America,”

the newspaper reported “It is a structure that would command admiration

in any land of palaces and castles grand, for in its design, its noble

proportions, and its artistic finish it is, in reality, a palace.”

And a palace it was.

With 130 rooms, four stories and an imposing corner tower, it was

modeled loosely after the Chateau de Blois in France. The joining of the

new addition to the original mansion was flawless and imperceptible.

While the main family entrance remained at 1 West 57th Street, the grand

port cochere entrance on 58th Street was used for social functions.

Through the great iron carriage gates and around the circular drive

would pass the carriages of New York’s most elite. According to

Valentine’s Manual of Old New York "Visitors lucky enough to be on this

spot during a social function will never forget the procession of smart

equipages, drawn by blooded horses, and manned by liveried footmen and

grooms, discharging passengers, each of them a society member of high

standing."

The interiors were meant to impress. The paneling and decorations of

LaFarge’s original dining room were incorporated into the billiards room

upstairs in the new section. The main 40 by 50 foot entrance hall on the

57th Street side was faced in Caen stone “after the French style

followed in the interior of the Chateau de Blois” (Saint-Gaudens’

magnificent mantelpiece had been moved upstairs to the new family

sitting room). The library faced 5th Avenue along with two salons, one

decorated in Louis XV the other in Louis XVI. On the 58th Street side

was a Moorish smoking room designed by Lockwood de Forest – the walls

encrusted with tiles and mosaics, the floors piled with Persian rugs.

Mr. Vanderbilt’s office and a breakfast room were also on the ground

floor.

The sumptuous 65 by 50 foot ballroom also faced 58th Street. It took

artist Edouard Toudouze nearly a year to complete the ceiling painting

in his Paris studio. According to a French critic “Cupids frisk about,

darting their love shots about rather carelessly” and “it is just the

right thing for a ballroom.”

Rather than build a “picture gallery” as was the trend in millionaire’s

homes, Vanderbilt lined the walls of his new dining room with his

paintings. Here hung two Turners, Constable’s “A Castle on the River Wye,”

two portraits by Sir Peter Lely, and works by Corot, Millais, Rousseau,

Greuze and Ruysdael.

The price tag in 1893 to enlarge his house was around $3 million

dollars. Vanderbilt could rest easy now –no one would consider an

attempt to outdo Cornelius Vanderbilt’s new home.

The Times article noted that Mr. Vanderbilt “has no fads or hobbies. He

is a man of strong domestic tastes and finds his chief enjoyment in the

family circle.” Alice Vanderbilt, according to the journalist, “is an

ideal wife and mother, refined and dignified, inclined to domesticity…”

And here this domestic couple lived happily until the morning of

September 12, 1899 when Vanderbilt unexpectedly died. That morning,

according to The New York Times, “A few minutes before 6 o’clock…he

awoke and, arousing his wife, said to her: ‘I think that I am dying.’”

Within five minutes Cornelius Vanderbilt II was dead of a brain

hemorrhage.

Alice Vanderbilt, according to The Times, “was prostrated” with grief

and required a doctor’s care. She never entertained again in her grand

ballroom. The windows were shuttered and the grand iron carriage gates

were seldom opened, then only for funerals or close family events.

Over time commercial buildings began crushing in on Alice’s mansion and

in 1926 she sold it to Braisted Realty Corporation for around $7

million. A week before the wrecking ball was scheduled to demolish the

40-year old home, Mrs. Vanderbilt arranged to have it opened to the

public for fifty cents admission which would be donated to charity.

Guests signed the Vanderbilt guest book and ogled at the stained glass

dome over the grand staircase and the French salons. A week later it was

no more.

Little survives of Cornelius Vanderbilt’s full-block chateau. The

Saint-Gaudens mantle is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the grand

carriage gates are installed at one entrance to Central Park, and some

of LaFarge’s stained glass and other pieces were salvaged. But the great

bulk of the Vanderbilt mansion was demolished along with an

irreplaceable page of New York City history.

Source-

http://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2010/07/not-to-be-outdone-cornelius-vanderbilts.html

|