|

When Spain Reigned on Central Park South

NY TIMES By CHRISTOPHER GRAY

STREETSCAPES | THE NAVARRO FLATS

THERE was only one developer who could give Edward Clark, the builder of

the Dakota apartment house, a run for his money. That was José Francisco

de Navarro, the Spanish-born entrepreneur of wide accomplishments and

appetites, including real estate.

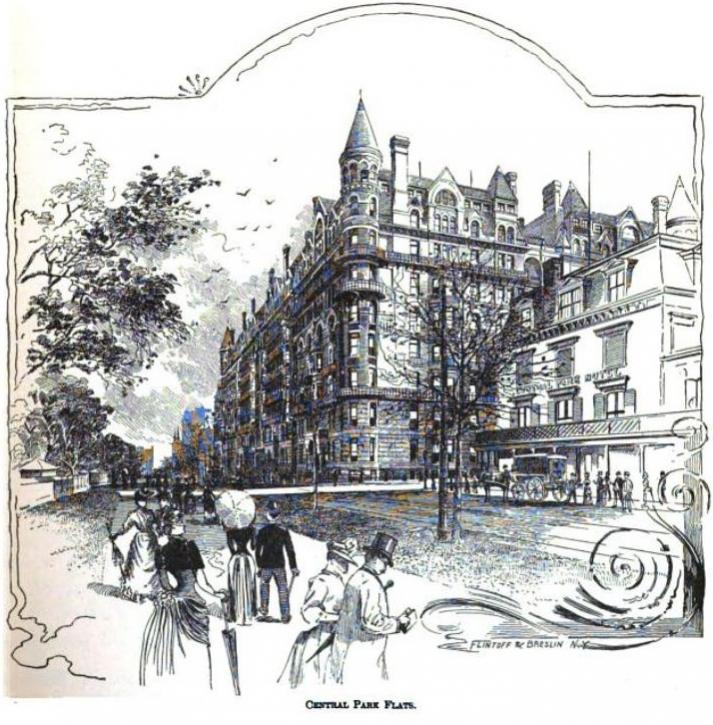

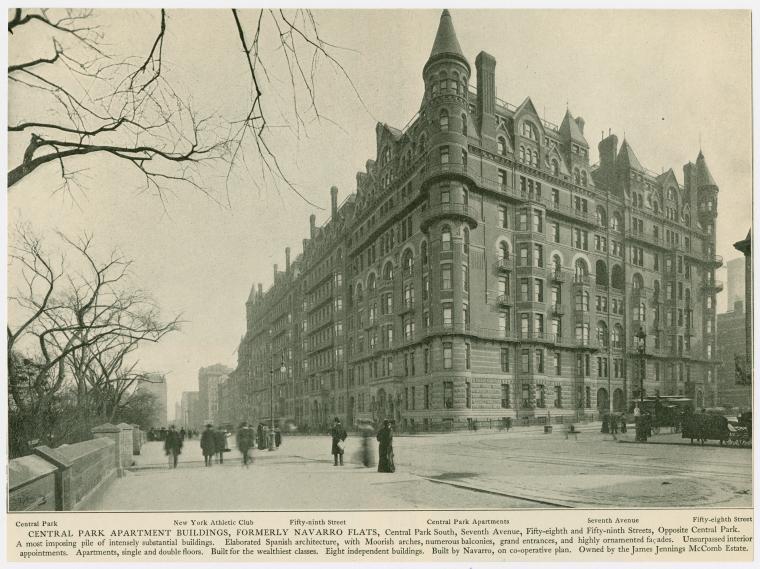

His gigantic eight-building Navarro Flats complex, built on Central Park

South in the 1880s, is long gone, but it was just as famous in its time

as the Dakota — if for all the wrong reasons.

Born in Spain in 1823, Mr. de Navarro graduated from the Spanish Royal

Naval Academy and came to the United States to teach at a Jesuit college

in Maryland. After a few years, teaching gave way to railroad

investments, then insurance, and by the 1870s he had a number of

successful enterprises, like providing $283,000 worth of water meters to

the Tweed ring, as well as collaborating on a public market with Boss

Tweed himself.

In the early 1880s, the advent of co-op apartments attracted a new kind

of builder. Previously, developers had either built and held for

investment, or built for sale to a new owner, being paid after the fact.

With the new co-ops, the developer began collecting money upfront from

future tenant-shareholders, who provided a new source of investment

funds.

In 1882, Mr. de Navarro began a project twice the size of the Dakota,

which was then in mid-construction. His was not one apartment house but

eight in a mammoth complex facing Central Park. They took up the

westerly end of the block bounded by 58th and 59th Streets, and Sixth

and Seventh Avenues, a site that was 425 feet long and 201 feet deep.

Although first called the Central Park Apartments, they soon became

known as the Navarro Flats or, sometimes, the Spanish Flats.

The buildings, each 13 stories tall, were named the Madrid, the Cordova,

the Granada, the Valencia, the Lisbon, the Barcelona, the Saragossa and

the Tolosa.

The sales brochure for the apartments, most of them seven-bedroom

duplexes, listed them at $20,000 for corner units and $15,000 for those

with only one exposure. Maintenance was $100 to $200 a month.

The architect, Hubert & Pirsson, staggered the floors so that the

principal rooms, facing the street, had extra-high ceilings. It’s a

comment on the times that the apartments had only two bathrooms each.

There were some particularly large apartments, about 7,000 square feet,

with a library measuring 19 feet by 22 feet, a drawing room 17 by 39, a

billiard room 18 by 24, and a dining room 16 by 31. “Not 10 houses in

New York” have such a scale of entertaining rooms, said The Real Estate

Record & Guide.

Unlike the cool beige brick and stone of the Dakota, the Navarro Flats

buildings were hot-red brick set off against a wild cliff of

stone-trimmed arches, turrets, gables and other features — an

arrangement that Scientific American called “most unsatisfactory” in

1884. There were some Moorish details, but the buildings were also

described as both Gothic and Queen Anne in style.

The construction chronology is hazy, but it appears that the westernmost

two buildings were completed in early 1884, the next two in 1885 and the

last four several years after that.

Mr. de Navarro was regularly reported to be involved in lawsuits and

troubled business affairs, but in 1884 he filed plans for apartment

complexes at 86th Street and Madison Avenue, and at 81st Street and

Central Park West. That year, The Record & Guide said that the Navarro

Flats “must have proved very profitable.”

By 1885, however, the publication reported that there had been few sales

and that there was “little doubt that the venture will prove to be the

reverse of profitable.”

The project required a second mortgage — and a third, which Mr. de

Navarro could not get. The scent of failure was death to further sales

or credit, and the mortgage holders were suing by 1886.

In November 1888, The New York Daily Tribune reported the cost of each

building as $2 million, and the complex was sold at auction, with at

least two of the buildings still incomplete. The original shareholders

lost their equity — or, as The Tribune put it, they had bought only

“castles in the air.”

The spectacular failure of the Navarro Flats put a damper on the nascent

co-op movement, which suffered from its failure for years.

Not that any stigma attached itself to living at the Navarro Flats. In

1890 the writer and reformer Carl Schurz lived in the Lisbon; Mary Mapes

Dodge, the author of “Hans Brinker, or The Silver Skates,” lived in the

Cordova; and Percy Chubb, the insurance executive, lived in the

Valencia.

Court battles relating to the project followed Mr. de Navarro at least

to 1902, when disappointed stockholders won a suit against him for

$950,000. That suggests he still had enough money to pay, and indeed in

the mid-1880s he had organized a successful cement company, which seems

to have occupied much of his time until his death in 1909.

Beginning in 1926, Mr. de Navarro’s towering vision was sold off

piecemeal, and the apartment buildings were replaced by the New York

Athletic Club, the Essex House and the Hampshire House, leaving not a

trace of those castles in the air.

Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company

***

|