|

New York Architecture Images-Gramercy Park 81 IRVING PLACE |

|

architect |

George Pelham |

|

location |

81 IRVING PLACE |

|

date |

1929-30 |

|

style |

Setback Style |

|

construction |

terracotta and brick |

|

type |

Apartment Building |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

images |

|

|

|

|

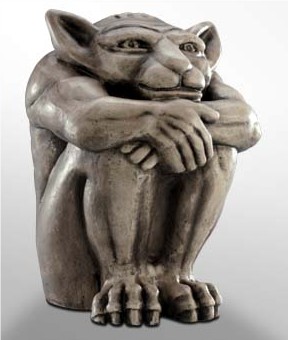

| For this 14-story apartment house, architect George Pelham, one of New York's most active apartment-house designers, exploited the requirements of the zoning law to create an exuberant design with dramatic setbacks and a striking rooftop pavilion surrounding the water tower. The building, planned with 107 small apartments, is faced with brick, often laid in intricate patterns to add excitement to the facades. The building is ornamented wth beige terra-cotta detail of a very high quality. Terra-cotta features include columns, balconies, and gargoyles embellished with animal heads, monsters, and other fanciful detail. | |

|

Winner at Work: The Facilitator By Alan Saly Myra Cohen, the president of a 101-unit co-op in the neighborhood of Manhattan’s Gramercy Park, is a facilitator. She makes things happen with a common sense approach to solving problems. “Maintaining a building is always a challenge,” she notes. “Electric rates are higher now, the union just got an increase, and fuel oil is three times what it was. You don’t want to keep passing on these increases. You want to make sure the building is operating as economically as it can. We rent out storage bins and bike racks. We have a laundry room which generates some income. We’re careful when we bid out contracts.” Careful – and busy. Although she is board leader and chief strategist, Cohen also wears two other hats – independent businesswoman and mother of two – yet she probably thinks that “burnout” is the name of an old Alec Baldwin movie. Burnout “probably happens,” she admits, “but we try to rotate responsibilities, and right now, the bulk of the work is getting done, and it’s getting done smoothly.” Indeed. In the past three years, she has guided the 71-year-old building through a mortgage refinancing, major capital improvements, renovations, and landscaping. And she doesn’t seem to be breaking a sweat. She has also gone into business with two partners, becoming vice president of a printing and graphics company that sells commercial printing to end-users and also owns three Mailboxes Etc. franchises. Nonetheless, she never planned any of this. Cohen and her late husband, David, were just looking for a nice place to live when they bought their first apartment at 81 Irving Place in 1984, two years after the co-op became effective. With income from their computer supply company, they purchased an additional unit next door in 1988 and then combined the apartments. The experience of running a business in a highly competitive environment made the idea of running a building seem a natural. David Cohen ran and was elected to the seven-member board as vice president. When he died in 1994, Myra was asked to fill in for the remainder of his term. Three years later, she must have been doing something right because she became president in her own right. The first major task testing her leadership came in 1997. Under the newly passed Local Law 11, the facade needed significant repairs. With the kind of diligence that won her a 2000 Habitat Management Achievement Award, she obtained refinancing of the co-op’s existing loan at an interest rate of 6.9 percent, two points lower than the old loan, which allowed for reduced payments while raising extra cash. Some of the money also went to major elevator upgrades: one car was converted from manual to automatic, and the other was completely overhauled mechanically. Cohen was just hitting her stride. Next came replacement of all the concrete outside the building, and installation of planters around the property. The improvements, which are culminating now in a full-scale renovation of the lobby, have remained within project costs, and the board has had to increase maintenance just once in the past five years. As for the future, she reports that 81 Irving Place is still being modernized. Once the lobby is complete, the board will have the upstairs hallways repainted and recarpeted. Both of her children are professionals, one a vice president at Chase, the other a partner in a law firm. Neither claim to be working harder than their mother – who has taken on her service as part of what it takes to live well. “It’s just like running a business,” notes Cohen. “When you run a co-op with that concept – as opposed to running it from a personal perspective – you can be successful in managing your maintenance and expenses.” Cohen finds she must also mediate between the shareholders of the building and a group of about 16 tenants who live in rent-stablized apartments still held by an investor, who took over the sponsor’s position. She knows that not everyone shares the same perspectives. “We play by the rules. If the board acts responsibly, then everything is fine, and most cooperators are reasonable – even if they are sometimes initially hot-headed. You sit down and talk and everyone can resolve their problems.” In addition to running the board, she supervises unionized staff of a super, handyman, and doormen. She says the key to it all is organization. “When we were in the throes of the Local 11 [capital improvement] work, that took a lot of time,” she recalls. “Other than that, it’s not as much time as you may think, if you manage your time properly. We have a very good managing agent who is extremely responsive, a good super, and board members who take an active part. I meet with the managing agent twice a month for an hour or so. Everyone does their job.” Resolving problems by working together isn’t easy, however, unless you have a facilitator who actually likes solving problems. Myra Cohen could be a model for that role. “I can make decisions by the seat of my pants,” she notes. “I don’t need to ask 55 people. We look at an issue together, we discuss it, and we make the decisions. Everyone has their input, and if you don’t agree with me on one decision, that’s fine; it’s behind us. A variety of opinions is part of the process. It’s not a bed of roses, it’s not a popularity contest. It’s who can do the job the best. People have to respect you. If they like you, that’s a plus.” |

|

|

Streetscapes/Irving Place; A 19th-Century

Street Honoring Washington Irving By CHRISTOPHER GRAY Published: May 18, 2003, Sunday IRVING PLACE, just south of Gramercy Park, is about to get back a bit of its past. Gramercy Neighborhood Associates, a local preservation organization, is arranging to put up, at its own expense, 16 historically accurate 1890's-style bishop's crook lampposts to replace the severely modern 1950's cobra-head fixtures that now line the roadway. Irving Place, which runs from 14th Street to Gramercy Park South between Third Avenue and Park Avenue South, was named in the 1830's by Samuel Ruggles as he was developing Gramercy Park. Ruggles apparently chose the name to honor Washington Irving, the author of ''The Legend of Sleepy Hollow'' and ''Rip Van Winkle.'' Development arrived at Irving Place in the 1840's, with houses of slightly less cachet than those along Gramercy Park. The first homes included the little brick house at the southwest corner of 17th and Irving, built in 1844. A few modest apartment houses crept in, among them the small 1840's building at the northeast corner of 18th and Irving, where Pete's Tavern now occupies the ground floor. The theaters that were strung along East 14th Street nibbled at the respectability of Irving Place's lower end. Oscar Wilde took rooms during his American tour in 1882 at No. 47, at 17th Street. But house owners were still willing to invest in their buildings. In 1879 John S. Foster, a flour merchant, had the architect Peter Tostevin design an oriel window bay for his house at 54 Irving Place. The railroad investor Stuyvesant Fish elegantly altered the large town house at the southeast corner of Gramercy Park South and Irving Place in the 1880's, and in 1893 Nicholas Fish, Stuyvesant's brother, had McKim, Mead & White alter his own house at 53 Irving Place. Gramercy Park and Irving Place were fashionable to the turn of the 20th century. But the bustle of the city was relentless. In 1893 the street was blocked by thousands of New Yorkers attracted to a publicity stunt. A lion -- ''Wallace, the Monster of the Jungle,'' according to The New York Times -- was said by the circus that owned him to have escaped his cage and be roaming around behind a wooden fence in a backyard just behind the apartment house at 18th and Irving. The Times was skeptical, and reported that the ferocious roars sounded manufactured. By the 1890's Irving Place was beginning to evolve from its more bourgeois origins. In 1897 the actress Elsie de Wolfe and the literary agent Elisabeth Marbury moved into the house at the southwest corner of 17th Street; it was apparently de Wolfe and Marbury who invented the still-durable tale, for which there is no foundation, that Washington Irving had lived there. Around this time the last of the old guard left Irving Place, one way or another. The Stuyvesant Fishes moved up to a new house at 78th and Madison; Nicholas Fish was found outside a saloon on West 34th Street in 1902 with his skull fractured; he died soon after in a hospital. It was an unexpected demise for someone listed in the Social Register whose lineage stretched back to the origins of the Republic and whose relatives included Hamilton Fish, who was governor of New York from 1849 to 1851 and secretary of state under Ulysses S. Grant. News accounts suggested that Nicholas Fish had begun drinking after his only son, also named Hamilton Fish, was killed in 1898 in Cuba in the Spanish-American War. Early 20th-century census returns show that many of the old dwellings had been converted to lodging houses. William Sydney Porter, who wrote under the pen name O. Henry, lived in a ground-floor room at 55 Irving Place from 1903 to 1907. He wrote his classic story ''The Gift of the Magi'' while living there. Porter's friend William Wash Williams, in his 1936 book ''The Quiet Lodger of Irving Place,'' recalled that Porter usually wrote his stories for The New York World overnight, turning them in at the last minute but always on deadline, and with clean copy. WILLIAMS remarked that Porter was ''as orderly and precise as the proverbial old maid -- in his rooms everything was kept just so, and his copy reflected the same qualities.'' In 1909 The Times reported that Irving Place was ''beginning to lose its quiet, secluded look'' and that the rear yard of the house at the southwest corner of 19th Street had just been destroyed, with seven stores created out of the building's 100-foot-wide ground floor facing Irving Place. Loft construction appeared at the lower end of Irving Place, but somehow the upper end held out against commerce. A design by the architect Herbert Lucas in the 1910's to tunnel under Gramercy Park to make Irving Place a southern extension of Lexington Avenue might have changed that, but the design was abandoned. According to the historian Richard McDermott, what many people now consider the most venerable name on Irving Place, Pete's Tavern, dates to 1926, when Peter Belles took over an existing bar. The Socialist Party leader Norman Thomas was living in an apartment in the old Stuyvesant Fish house when he ran for president of the United States in 1944. Many of the surviving old houses were extensively remodeled in the mid-20th century -- 70 and 82 Irving Place, which are now attractive late Moderne buildings, were created out of older buildings in the early 1940's and the early 50's respectively. More recent work has tended toward the banal, like the row houses at Nos. 51, 53 (the Nicholas Fish house) and 55 (where O. Henry lived), which were combined and given a fake brick facade in 1972, a project designed by Max Wechsler. The Gramercy Park Historic District, created in 1966, runs down the east side of Irving Place to include Pete's Tavern. Since then the little preservation activity on the street has included the conversion in 1993 of the old Foster House at No. 54 into the Inn at Irving Place. The replacement of the cobra-head lampposts -- which were designed in 1958 -- with 16 of the bishop's crook ones is moving ahead. The bishop's crook lampposts, which have gone up elsewhere in the city, cost about $4,000 each, said Nordal McWethy, the president of Gramercy Neighborhood Associates. Mrs. McWethy said that the replacements would be delivered to the Department of Transportation this month, with installation scheduled later this year in the same locations as the cobra heads. Bishop's-crook installations are quite common these days, but Mrs. McWethy said that the group had been required to shepherd its proposal through Community Boards 5 and 6 (each has jurisdiction over part of Irving Place), the Landmarks Preservation Commission and the Art Commission. If the project had been to replace the cobra heads with identical ones, she said, no change would have occurred and the group would not have been required to submit the project for review. From the grand mansions that once marched along Fifth Avenue to the jammed tenements of the Lower East Side, New York's buildings both trumpet and conceal the intensely human stories of those who built, designed and inhabited them. For 15 years Christopher Gray has been teasing out the stories behind hundreds of New York City buildings from dusty records and private memories, and telling them in these pages. ''New York Streetscapes: Tales of Manhattan's Significant Buildings and Landmarks,'' a 448-page paperback (Harry N. Abrams, $35) brings together 190 of these columns, and archival photographs of the buildings. Included are the story of the Chrysler Building's secret spire, the trump card in a grudge match between two architects; the location of New York's oldest surviving bar; and how an apartment building that became synonymous with luxury, the Dakota, got its unlikely name. Noted architects and captains of industry appear, as do servants and tenement dwellers, the aviator and writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (sailing paper helicopters out of the window of his Central Park South apartment) and Ernest Vernon, the butler in one of the last mansions on Fifth Avenue, weeping alone at his employer's funeral. Published: 05 - 18 - 2003 , Late Edition - Final , Section 11 , Column 1 , Page 7 Copyright New York Times. |

|

| links |

www.preserve2.org www.aardvarkelectric.com |

|

links |

|