|

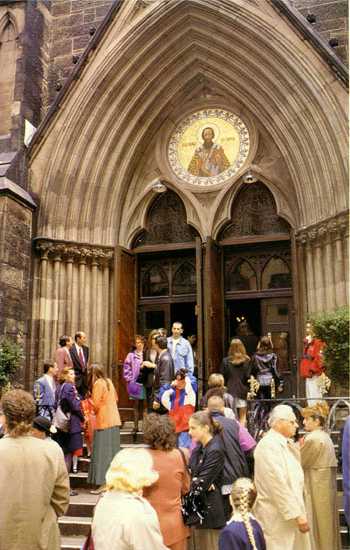

New York Architecture Images-Gramercy Park Serbian Orthodox Cathedral of St. Sava |

|

architect |

Richard M. Upjohn |

|

location |

15 West 25th St. |

|

date |

1852-55 |

|

style |

Gothic Revival |

|

construction |

stone |

|

type |

Church |

|

|

|

|

images |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

notes |

1852-55 by Richard Upjohn, built originally as a chapel of ease to Trinity

church, Wall Street. Called "Trinity Chapel", its future was already under

threat in 1915. However it was to be another 27 years before the church was

sold to the Orthodox church, November 1942. It was reconsecrated in 1944. A

bomb explosion in 1960s (which targetted the communist Party's HQ on W26th

St) destroyed the original stained glass in the apse which enabled the

congregation to insert windows to Orthodox saints. A carved oak iconostasis

was inserted in 1961, and icons painted up to 1968.

Special thanks to

www.churchcrawler.co.uk

(British and international church architecture site) for generous

permission to use images and info. The son of Stefan Nemanja, the great Serbian national leader, he was born in 1169. As a young man he yearned for the spiritual life, which led him to flee to the Holy Mountain, where he became a monk and with rare zeal followed all the ascetic practices. Nemanja followed his son's example and himself went to the Holy Mountain, where he lived and ended his days as the monk Simeon. Sava obtained the independence of the Serbian Church from the Emperor and the Patriarch, and became its first archbishop. He, together with his father, built the monastery of Hilandar and after that many other monasteries, churches and schools throughout the land of Serbia. He traveled to the Holy Land on two occasions, on pilgrimage to the holy places there. He made peace among his brothers, who were in conflict over their rights, and also between the Serbs and their neighbors. In creating the Serbian Church, he created the Serbian state and Serbian culture along with it. He brought peace to all the Balkan peoples, working for the good of all, for which he was venerated and loved by all on the Balkan peninsula. He gave a Christian soul to the people of Serbia, which survived the fall of the Serbian state. He died in Trnovo in the reign of King Asen, being taken ill after the Divine Liturgy on the Feast of the Theophany in 1236. King Vladislav took his body to Mileseva, whence Sinan Pasha removed it, burning it at Vracar in Belgrade on April 27th, 1594. Prologue from Ohrid, translated by Mother Maria History Of The Cathedral The Serbian Orthodox Cathedral of St. Sava In New York City What became St. Sava Cathedral in 1944 officially began in 1850 as Trinity Chapel. In the late 1840's, the Episcopalian Trinity Church located on Broadway and Wall Streets in lower Manhattan, former parish church to founding father Alexander Hamilton, realized that New York City's "midtown" residential area was rapidly developing. The character of the Wall Street neighborhood, once exclusively fashionable, was rapidly becoming a commercial district. Trinity was losing its congregation because of its location. People could no longer be counted upon to make the long trip down to Trinity from the newly residential areas of Washington Square or Union Square. On November 2, 1850, in order to stem the tide of defections by parishioners, the Committee of Church Extension decided to purchase land to erect a chapel in "upper New York." Trinity fixed on a parcel of 5 lots (which were to be followed by three more) just off Fifth Avenue which it promptly purchased from the proprietor, Mr. Drake. Highly satisfied with his now famous work on Trinity Church, the committee turned once again to Richard Upjohn, the foremost architect of his day, to build the new structure, thus ensuring a continuity of style. Progress apparently was rapid, since records of a March 1852 meeting show the rector was asked to arrange the cornerstone laying just two years after the original planning. However, as with all building construction, costs increased as modifications and alterations were made. The original plans for the chancel were changed, and the interior walls, originally to be of light brick were changed to Caen stone imported from Northwestern France. These, as well as other alterations, eventually raised the original cap from $40,000 to $79,000 to $230,000 upon the chapel's completion. In his record of church history, the Rev. Morgan Dix, rector of Trinity, dryly observed: "The persuasive power of architects and the docility of building committees must always be taken into account when estimates for new structures are taken under consideration. " The architectural style of the church, early English Gothic, was considered unique on the continent at that time. Among its more unusual and immediately apparent aspects were the lack of a tower and the lack of ornamentation. Its fine proportions, and edifice, rugged, but pleasing in character, reinforced with large buttresses, quickly won Upjohn acclaim as did the picturesque and charming Clergy House attached to the rear of the building. But it was the interior of the chapel which has often been assessed as Upjohn's masterpiece. Its loftiness and brilliance of proportion make it entirely different from anything else of its time. The most striking features, the long single aisled nave and open roof ceiling, resemble St. Louis' 13th Century Sainte Chapelle in Paris. When combined with the fully exposed truss ceiling of Norway pine, the beautifully polychromed panels with gold stars on a field of blue, and the painted apse walls (by German artist Habastrak), the chapel interior becomes as ecclesiastically proper as its Mother Church. On the second Tuesday after Easter, 1855, the new chapel was consecrated with a large congregation present. Very shortly, a fashionable and wealthy congregation filled the chapel. Trinity was the only one of the six chapels in the parish in which pews were rented (the numbers still exist on the outside of the pews ). The records list the names of 125 parishioners who held pews between 1855 and 1856. It was only a simple wedding, but 30 years later, Pulitzer Prize winning author Edith Jones was married to Edward R. Wharton in April of 1885. The wedding was arranged by the bride's mother who lived across the street. A few years later Edith Wharton would immortalize the society and the church where she was married in her The Age of Innocence, the classic novel of Victorian New York. By 1874, Trinity was a thriving center of evangelism. That year there were 648 communicants, 30 baptisms, 20 weddings, 47 confirmations, and 28 burials. The Sunday School had 39 teachers and 325 students; the Industrial School 35 teachers for 255 students and the daily Parish School which was free, had two teachers for 83 students. In addition, the chapel sponsored the Missionary Relief Society, the Sisterhood of the Holy Cross, the Mothers Aid Society, the Employment Society of Trinity Chapel, and the Trinity Chapel Home for Aged Women. At the turn of the century, the area around Trinity Chapel began to change, becoming more commercial, as it once did around Trinity Church. The Episcopal Diocese realizing that families were beginning to leave the area for more fashionable parts of the city sent the Rev. J. Wilson Sutton in 1915 to serve as priest-in-charge until the chapel could be closed and the property sold. The shocked parishioners rallied around the dynamic leadership of Rev. Sutton, who in order to raise spirits and derail the planned sale began to beautify the chapel by adding carved oak choir stalls in 1931 and by commissioning the artist Rachel Madeley Richardson to do a series of religious paintings in the 14-foot wall niches located along the nave. Begun in the 75th anniversary year of the chapel, the project occupied Miss Richardson for ten years and was dedicated in the spring of 1940. But the effort of holding off the sale of the property was not to be. Within two years after commissioning future viability studies, the Trinity Corporation decided to sell 3 chapels in the system: St. Agnes, St. Augustine and Trinity Chapel. When word leaked that Trinity would be sold, Russian, Greek and Serbian Orthodox congregations became interested. Ironically, Trinity Chapel's ties to the Eastern Orthodox Church extended back to March 1865, when the Divine Liturgy of the Eastern Orthodox rite was celebrated for the first time in an Episcopalian church in America. The next day the New York Times and other papers covered not only the American Civil War, but also the liturgy with headlines reading; "A Novel Religious Service", "A Remarkable Event in History" and "Inauguration of the Russo-Greek Churches in America". The organization of the Serbian Orthodox Congregation that eventually purchased Trinity began when a group of Hercegovinian friends met on May 6, 1937 (St. George's Day) in Corona, New York at the Stajcich-Boro home of Vido and Petrice Stajcich. Five others were present as well: Nikola Boro, Ilija Grbich, Djura Vujnovich, Krsto Gasich and Petar Soldo. After initial conversation, they began to regret the fact that there was no church in which the devoted could meet. One thought led to another, and after the initial conversation the group became confident and enthused enough to each pledge a donation. As word of a proposed church spread, other Serbs rallied to the cause. The community of Serbs, though small, was not afraid to assume the sacrifices and immense preparations of starting a church in New York City. Anxious to establish their church according to New York State laws, a petition and articles of incorporation were written and signed by Djura Davidovich, Nikola Boro, Mirko Baranin, Ruza Triklovich, Djura Vujnovich and Lazar Balich. On March 20, 1940, under the name of Srpska Istochna Pravoslavna Crkva Svetoga Save u New Yorku (Serbian Eastern Orthodox Church of St. Sava in New York) the first Serbian Church in New York City officially began. Since it was not financially possible to purchase a church immediately, services were held at different locations. The first of these locations was the original meeting house for the oldest Serbian organization in America, the Serb National Benevolent Society, (1869), located at the Hartley House, 413 W. 46th Street in Manhattan. The premises were found to be suitable, and Rev. Vojislav Gachinovich was found to officiate. However, Rev. Gachinovich's term ended shortly thereafter. As result of questionable political activities he was removed from the parish and defrocked by the Church Consistory of the Serbian Orthodox Diocese due to his communist inclinations. On January 1, 1942, Rev. Dushan Shoukletovich of Gary, Indiana, arrived in New York and took charge of the parish. Within a year a fire-damaged property at 25 E. 22nd Street was purchased with the intention of converting it into a church. While the Serbs still held this property, Bishop William Manning, Episcopal Bishop of New York, provided them with the use of an interim church building located on East 116th Street in Manhattan. A short time later, a remarkable development materialized. Church Board President Dushan B. Tripp and his officers were called to be apprised of the availability of the West 25th Street Trinity Chapel by the Trinity Corporation of New York. After many years of sacrifice and prayer it now seemed that a Serbian Orthodox Church in New York City was becoming a reality; but not until one last obstacle was overcome: for a short time it was not certain that the property would pass to the Serbs because of a lack of funds. By the time the Serbs became aware of the property, the Episcopalians had already turned down two earlier offers to buy the church from both Russian and Greek congregations. Aware of their limited financial capabilities Mr. Tripp was ashamed and hesitant to offer any amount. However, because of the insistence of the Trinity Vestry he made an offer of $ 25,000 (the same sum offered earlier for a much smaller church). The Board of Directors of the Trinity Corporation accepted the offer requesting that the sum be raised to $30,000 for which the Serbs would also receive all the furnishings in the house, two valuable pianos, a satisfactory reserve of coal and a variety of church objects. They happily agreed and began to search for a way to actualize the bargain. The decision in favor of the small but dynamic Serbian congregation was made by the vestry, and rector of Trinity Parish, Dr. Frederick S. Fleming, for a number of reasons. First, it would be the only Serbian Orthodox Church on the East Coast. Second, it would draw a congregation from New York City and surrounding areas. Third, the project was supported by His Majesty King Peter II along with Canon Edward N. West, Sacrist of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York, Bishop Nikolai Velimirovich and most significantly, Bishop Manning. Manning, who along with Canon West shared a particular fondness for Serbs and often spoke with great emotion of the suffering of the Serbian people during the war. He enthusiastically quoted St. Sava, and was familiar with the history and traditions of the Serbian Church and her people, whom he considered to be part of his spiritual flock. He was also very proud that one of the three Bishops at his consecration was Bishop Nikolai. As the paperwork and legal parameters were being established, the property on E. 22nd Street was sold in late 1942 with the proceeds going toward the new church; but it was hardly enough. The congregation turned to the SNF for assistance, but received only moral support. After a nationwide campaign, additional money was collected from immigrant pioneers of Serbian descent already in the United States, but again the amount was too little. Running out of time, Mr. Tripp, a Vice President at Chase National (Manhattan) Bank, turned for help to his personal friends, and received from them the amount necessary to consummate the agreement. In November 1942, notices were published indicating that the property had been sold to the Serbian Eastern Orthodox Diocese for the United States and Canada. The dream had finally materialized. After so many years of hard work and persistence, the New York City congregation, which until one year ago had held services wherever it could manage, now had the largest Serbian Church in all of America! The terms of the agreement were "cash over a purchase-money mortgage of $30,000", and included a clause giving Trinity Corporation the right to repurchase if the buyer discontinued using the property for religious purposes". It was as future Dean of the Cathedral Rev. Shoukletovich wrote to Dr. Fleming, ". . . a matter of Church to Church, to continue God's work among those that have been deprived of that privilege in the past". Title passed to the Serbians on the first of March 1943 with Dr. Fleming explaining in the New York Times that it "would become a real center . . . with religious, educational, and cultural contacts" for the Serbian Orthodox faith. On June 11, 1944, with over 1,400 Serbian-Americans present, the church was consecrated by the late Bishop Dionisije with Bishop Manning participating. Among the clergy present were: Rev. Dr. Frederick Fleming, Canon West, Bishop Polizoides, representing Archbishop Athenogoras of the Greek Archdiocese, Bishop Makarije of the Russian Orthodox Church, five Serbian Orthodox priests from America, and St. Sava's very own Rev. Dushan Shoukletovich. Lay attendees were Constantin Fotich, the Yugoslav Ambassador-in-Exile, Assemblyman John J . Lamula, who represented New York Governor Thomas Dewey, and George Philles of the Greek Orthodox Church in Buffalo, N.Y. The kum at the consecration was Mr. Bozidar Martinovich of Gary, Indiana. This impressive service, as the one 75 years earlier, symbolized the close friendship between the Episcopal and Holy Orthodox Churches. Prayers were offered in "full and complete fellowship in the faith of the Lord and Jesus Christ" (two years later the Cathedral Choir of St. Sava would sing at the 150th Anniversary of the 1796 founding of the Trinity Church Parish). A reception dinner followed at the Hotel McAlpin on Broadway and 34th Street, and the next morning Serbs all over New York woke to Monday's New York Times headline: "Serbians Dedicate Cathedral in City." Though the dream of having a Serbian church in New York City was now realized, the real work of creating a cohesive parish was to follow. Without the vision, charisma and organizational abilities of Rev. Shoukletovich the church may not have progressed into such a viable and important Christian community so quickly. If any one person can be singled out for seeing to the proper development of the Cathedral in its formative years it was he. A Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, and former attorney, Rev. Shoukletovich spoke fluent Serbian and English, an important factor in communicating with both immigrants and the American born. His persistence, wit and familiarity with the intellectual currents of his time, combined with his unwavering faith and optimism made Rev. Shoukletovich the perfect minister for New York City. For 14 years, Father Shoukey (as he was affectionately called by his congregation) enthusiastically worked to enhance parish spiritual life as Dean of the Cathedral. Skillfully and wisely, he led his congregation in times of war, and of peace, when prosperity was enjoyed and when economic uncertainty affected the lives and circumstances of his parish. Blessed with the ability to truly inspire others, he moved a tiny group of Serbs to accomplish more under his leadership than they ever considered possible in their private thoughts. On November 21, 1951, he was given the Grand Cross of St. Sava Third Degree by King Peter II, and appointed by his decree as Instructor of Religion and Serbian Language to Prince Alexander. Shortly before his retirement from the Cathedral, in April of 1955, Rev. Shoukletovich was given the Medal of St. Joanikije (the first Serbian Patriarch in the 14th Century) and was awarded the title Dean Emeritus for life by the Board of the Cathedral. He passed away in 1981 in San Diego, after further associations with St. Elijah Church in Merriville, Indiana, St. Petka Monastery in St. Marcos, California and other parishes throughout the west. As capable as Rev. Shoukletovich was at administering the Cathedral, it would not have flourished without the commitment of the Cathedral Executive Board, the Auditing Board and the Board of Trustees. Responsible for the temporal obligations of the Cathedral, the Executive Board - headed by Dushan B. Tripp (Tripcevich) saw to its proper direction. A dignified man, and a respected and successful banker, Mr. Tripp (as everyone called him) together with Rev. Shoukletovich, saw to the establishment of proper administrative procedures, a Circle of Serbian Sisters (St. Petka), the development of a Christian social life, a youth group (Omladina), and an active church choir led by several enthusiastic directors over the years such as Madam Slavianski, Michael (Misha) Boro Petrovich, Deacon George Lazich, Dushan Georgevich and future priest, Dragoljub Sokich. Mr. Tripp, a former secretary in Michael Pupin's Sloga served as Cathedral President for almost 10 years. His distinguishing presence, and accomplished demeanor added a sense of integrity and respectability to those early critical years. In its early years, the Cathedral served as a magnet to Serbs from all areas of the country and the world. Academy award winning actor Karl Malden found his way to St. Sava's on occasion during his early theater days, as did actor Brad Dexter, and the 1950 Rookie of the Year Walt Dropo of the Boston Red Sox. King Peter II then in exile. participated in church services with Queen Alexandra and their son Crown Prince Alexander. On the occasion of his first visit to the Cathedral in 1944 he was led in by a colorguard of the American-Serbian Society carrying a banner presented to them many years before by his grandfather King Peter of Serbia. During his sermon, Rev. Shoukletovich addressed the congregation saying: "As we celebrate Easter . . . thousands of Serbs who are starving and homeless in Europe look to this King as a symbol of unity . . . no bells will ring in the towers of the churches in Yugoslavia this Easter to call the faithful to prayer because God has been forbidden by the unbelievers ruling the country. Today in Yugoslavia, as during the first Easter, people meet behind closed doors and greet each other with whispered words of: 'Christ is Risen'. The time will come when the young King will go back to a free Yugoslavia and take his rightful throne. Long live the Kingdom of Karageorgevich!" The Cathedral was also a magnet for people of less renown as well. Throughout the ten year immigration, wave following World War II, the Cathedral provided the only meeting ground for Serbs in New York City. The new immigrants clung to their Serbian language, traditions and customs in the new world. They felt the need to preserve their native cultural patterns, and the Cathedral provided the forum. But the Cathedral was also instrumental in helping the newcomers assimilate into their new nation, helping them adjust, to learn its language, customs and democratic principles. It also provided them with Christian fellowship and understanding as well as financial help. For a great many years young men new to the city slept in the Cathedral's third floor offices for a night or two until they found jobs. Eventually many of these immigrants moved on to other destinations, some even to help found new churches in other areas of the country. The spirit of any church era is clearly marked by the lives, writings and influences of her apostles. Among these luminaries stands the late Bishop Nikolai Velimirovich, who during the post war years made St. Sava Cathedral his home. A prolific writer and eloquent orator; a prophet and visionary; a mystic and apologist; an effective archpastor and a diplomatic statesman; Bishop Nikolai's presence at the Cathedral created a sensation and a feeling of specialness. The echelon of intellectual society in New York City flocked to him spellbound. His beloved Srbiantsi trailed him night and day asking questions and advice about their concerns, all of which he found time to respond to during his busy schedule. Bishop Nikolai's presence at St. Sava Cathedral, which began in 1948, provided a great source of hope, courage, and grace to the parish. He seemed to be everything to all people, not only a Bishop, but also close friend. As "luminary-in-residence" and "elder statesman", parishioners would respond in kind with great love and attention by seeing to it that meals were provided for him, his living quarters maintained, his sermons typed, and that he would not forget to take his medicine, which he would mischievously do from time-to-time. Bishop Nikolai served St. Sava's Cathedral while teaching at St. Vladimir's Seminary in Crestwood, NY. Shortly before his death he left the Cathedral to teach at St. Tikhon's Seminary in South Canaan, PA, where he continued to commune with his spiritual children in New York City in letters and telephone conversations. On the morning of March 18, 1956 the news reached the office that Bishop Nikolai had passed away during the night. Funeral services at the Cathedral were arranged where Bishop Nikolai laid in state for three days before being buried at St. Sava Monastery in Libertyville, Illinois. Among Bishop Nikolai's many friends and admirers was Canon Edward N. West. Canon West was a remarkable man who became deeply involved with his Orthodox Christian friends in the New York area. The inception and early history of the Cathedral would be very different were it not for him. With a dramatic and flamboyant personality, Canon West was well respected by the St. Sava parish and enjoyed his part in the cultural life of the Cathedral by attending functions at the hall where he would indulge in his love of Serbian food, particularly sarma. Through Canon West's Anglican contacts in England following WWII, he arranged to bring to the United States five young Serbian men: Mihailo Jovanovich, Veselin Kesich, Milan Kovachevich, Bogdan Mishkovich and Dragoljub Sokich - all to study at Columbia University, and St. Vladimir's Seminary, providing for their scholarships and housing, while at the same time being their kind friend. To that group, Bishop Nikolai asked that two more students be added - Zoran Milkovich who was already in the United States, and Milan Savich from Europe. West agreed and further responded with his usual keen interest in assisting and encouraging other Serbian students to join St. Vladimir's Seminary. Throughout the years, Canon West, Knight Commander of the Royal Order of St. Sava remained a faithful friend to the Serbian Orthodox of New York City. He passed away on January 3, 1990 in his quarters at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. Following the retirement of Rev. Shoukletovich, and a brief stay by Rev. Dushan Klipa, Rev. Firmilian Ocokoljic was installed as new Dean of the Cathedral. A benign and comforting man, Rev. (and subsequently Bishop) Firmilian moved to consolidate the impressive gains made in the prior years. Led by his effective and intelligent guidance along with the important contributions of assistant priest, Rev. (and subsequently Bishop) Vasilije Veinovic, the Cathedral built up the largest Serbian community in the United States. Throughout his tenure St. Sava's continued as an active parish where many people came to participate in the wonderful cultural and spiritual life the Cathedral offered. They came to hear visiting dignitaries, speakers and lecturers such as former cabinet members and ambassadors of King Alexander I, artist Danilo Popovich a successful painter of his time with offices both in Rome and New York, and to help Prince Tomislav and Princess Marguerita celebrate the Karageorgevich Slava, St. Andrew's Day, in the Cathedral Hall. During this period the Cathedral under the committeship of Dushan Tripp and Tihomir Topalovic unveiled the bust of Dr. Michael Pupin in the Cathedral courtyard. A year later it would also place one of Bishop Nikolai through the efforts of his former students. Throughout the 1950's and 60's the Cathedral also endorsed the immigration of hundreds of individuals from the former Yugoslavia through the Church World Service under the Refugee Relief Act of 1953 by the Department of State. Unfortunately, in the early 1960's a tragic and unfortunate schism occurred in the Serbian Orthodox community across the United States and St. Sava's in particular. This sad period, lasting over 25 years, created an unpleasant split with two opposing "sides". It was never a religious or doctrinal division as each side was still committed to its Orthodox faith, dogmas, spirit and love of St. Sava, but nevertheless it tore the Serbian community apart. History records that the Orthodox Church has always struggled and survived over the centuries. For almost 500 years, the Serbian Church and its people survived the Ottoman invasion of the Balkans, and as it did in medieval Serbia, history and events would continue in New York. Throughout the 1960's, the buildings making up St. Sava Cathedral began to undergo renovation. Major repairs to the social hall were made in the mid and late 1960's under the leadership of Board of Trustees President George Perunichich. These repairs included adding steel beams to reinforce the 100 year old hall floors which sagged dangerously under the weight of kolo dancing. A devoted man to his church, Mr. Perunichich also worked to make the Cathedral self sufficient. For almost 20 years the Cathedral struggled to make ends meet each month, but by transforming the courtyard into a parking lot during the week for nearby shop owners and by continuing upgrades in the cathedral brownstone (which a decade before had undergone renovation that created a series of smaller apartments), Mr. Perunichich finally solved the nagging problem. Major repairs were made to the Church as well, due to a significant bomb explosion at 23 West 26th Street, the former headquarters of the Communist Party in New York. The explosion ripped through the neighborhood and destroyed the original stained glass windows of the Cathedral apse. A major fund raising drive was initiated to replace the windows and stabilize the building which was beginning to show its age. While regretting the loss of the original windows, the Cathedral moved in order to add the current Byzantine style windows, with their Orthodox saint associations. Another addition to the interior of the Cathedral was the crystal and gold chandelier above the nave (donated by the Perunichich Family), which continued a long process of adding Byzantine elements to the original Gothic interior, thus further distinguishing St. Sava's in the family of New York City churches. The first such Byzantine style addition in 1961, commissioned by Executive Board President Jovan Tomich and Secretary Bogdan Mishkovich was the hand carved oak iconostasis created in the tradition of 10th century religious art. Painstakingly researched by the two, and hand carved by craftsmen at the Monastery of St. Naum in Ochrid in South Serbia, the new altar piece was dedicated on June 24, 1962. The artistic detail and great beauty of the iconostasis represented an artistic milestone for it was the first altarpiece in the tradition of Byzantine art to arrive in the United States. Its 40 icons were painted by Prof. Ivan Meljnikov, a refugee of the Russian Revolution and a highly regarded exponent of Byzantine iconography. On April 18, 1968, a few months before the installation of the new stained glass windows, the New York City Landmark Preservation Commission officially proclaimed The Serbian Orthodox Cathedral of St. Sava a landmark of the City of New York stating that its "striking appearance commands special attention" and that its "special character, historical significance and aesthetic interest and value as part of the development, heritage and cultural characteristics of New York City" make it irreplaceable. As the Cathedral commanded special attention with authorities dedicated to preserving historical structures, it also continued to do so with its parish as well. Under effective guidance in the early 1970's by the Bishop Vasilije and the Executive Board of Tihomir Topalovic, and after a new wave of immigration, the Cathedral's membership rolls approached the startling figure of over 700 members. The Cathedral social hall, which usually is capable of housing large yearly assembly attendances, could not handle the large numbers. Arrangements were made during these years to hold assemblies at large banquet halls around the city such as the St. George Hotel in Manhattan. The astounding growth in only 25 short years had managed to place the Cathedral's membership at one of the highest numbers in New York City, rivaling such eminent churches as St. Thomas Church and St. Patrick's Cathedral! The social life of the Cathedral continued as well. King Peter II continued to attend services at the Cathedral and take part in its activities. His moving final visit shortly before his death, occurred in 1970. For over 30 years in exile, King Peter had found at St. Sava's a warm home with many friends. Most recently, another generation of Karageorgevich has become associated with St. Sava's. In 1990, following an absence of 41 years, King Peter's son, Prince Alexander Karageorgevich attended services at the Cathedral. The reception at the social hall attracted more than 500 people where Prince Alexander spoke briefly about the then impending crisis and civil war in the former Yugoslavia. Last in attendance as a child of 9 years, tears welled in his eyes as memories flooded back, and well wishers swarmed toward him in outward demonstrations of emotion once granted his father in 1945. In December of 1982, St. Sava Cathedral achieved one of the highest designations granted a building in America. The United States Department of the Interior officially placed the 128-year-old Cathedral on the National Register of Historic Places acknowledging its value as an important landmark in the historical development of the United States. St. Sava Cathedral could now officially claim its rightful place among the great family of churches and cathedrals along New York's avenues. Currently St. Sava's is working to obtain the same distinction to the social hall. The whimsical Parish House, is the last remaining building in New York City designed and built by noted architect Jacob Wrey Mould. Within the last few years, the gap between the Cathedral's two communities has slowly and hesitatingly started elevation to Patriarch, began the unification and healing process in very recent years. On Monday, October 5, 1992, his Holiness, as part of a larger trip to across the country, traveled to New York City, where a doxology service was held at the Cathedral attended by over 1,300 people. It was the first time a Serbian Patriarch had ever visited America. While in New York City for three days, His Holiness visited the National Council of Churches, attended a vesper service and banquet at the Greek Archdiocese with Archbishop Iakovos, and met with Secretary General of the United Nations Boutros Boutros-Ghali to discuss the terrible civil war in the former Yugoslavia. Part of the legacy of his visit will be, with God' s help, more trust, more cooperation, and eventually complete and true unity. Most recently the Serbian Orthodox population of New York City has begun to finally realize that only through true reunification can the Cathedral grow and address the challenges facing it at the dawning of a new century. Today with its aesthetic grandeur and structural integrity threatened, the Cathedral is in need of serious renovation. Over the many years, its roof and drainage system have slowly deteriorated, moisture has broken through the envelope of the building, and its resistance to the elements, severely compromised. Through grants and donations, the Cathedral has begun the expensive and important process of restoring and repairing the largest, the first, and the most historic Serbian Orthodox Cathedral in the United States of America. |

|

By Lana Bortolot Special to New York Resident In recent years, the stretch of Sixth Avenue running through the heart of Chelsea has been one of the city’s hottest construction corridors. Towering apartment buildings have shot up here — particularly in the blocks between 23rd and 27th Streets — creating a supercharged housing market and changing the scale of this genteel neighborhood. It’s typical of this city that while so many buildings rise, others fall. Such is the case of one landmark building in this neighborhood, the Serbian Orthodox Cathedral of Santa Sava. Tucked away on West 26th Street, nearly lost in the shadow of modern towers such as the Vanguard and the Capitol at Chelsea, the 150-year-old Early English Gothic cathedral literally struggles to keep the roof over its head, despite its impressive pedigree. Designed by Richard Upjohn, it was built as a northern outpost of Trinity Church in one of Manhattan’s then most stylish neighborhoods. Edith Wharton married here the year it was completed, 1855. When the Serbian parish bought the brownstone church 60 years ago, it was in a sorry state. Chronic lack of care over the decades, including abandonment for many years, resulted in significant water damage to the supporting structure, particularly to the slate roof. “The roof is amazingly high and takes an enormous amount of wind load,” said preservationist William Stivale, the church’s architect. “If everything is in great shape, the [roof’s] truss system works fine. But water had been pouring into the top of the walls for years, weakening the structure. “What’s very special about this cathedral is that it’s made of caen, a French stone. It’s a very respected material, but it’s not supposed to get wet. It’s almost the consistency of talc, and when it gets wet, it literally disintegrates,” he said. Parish president Mira Luna recalls the enormity of the restoration, which is being executed in stages with the technical guidance of the New York Landmarks Conservancy. “When we began, pieces of the roof were flying all over Sixth Avenue,” she said. But before the roof could be repaired, the entire building had to be stabilized and the walls repointed. Since 1999, approximately $2 million has been raised, but a total of $3.5 million is needed to complete the roof and for ongoing projects such as restoring the 16 stained-glass windows ($20-$30K each) and updating the electricity. Upjohn’s rose window was restored in 1998 through an anonymous donation. The New York Landmarks Conservancy has provided some relief with funds through the Booth Ferris Foundation and the Robert A. Wilson Sacred Sites program. And the church has relied on grass-roots fundraising — through flea markets, private donations, and an anniversary gala each fall. However, Santa Sava’s fourth request for a grant from the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation was recently rejected, and now the Rev. Father Djokan Majstorovic, cathedral dean, and Luna must appeal to parishioners for more donations. One challenge, says Father Majstorovic, is reaching out to a small community that doesn’t have a legacy of giving to its church. “[Our parishioners] come from a country where faith was forbidden,” he said. “So people aren’t used to practicing religion and financially supporting it.” Moreover, he is pressing a congregation already tapped out from sending funds home to a country still restoring itself after the war. The efforts to date have included direct mailings, which cost $900 to execute and result in few returns. So Santa Sava hired a professional fundraiser who has already initiated a community outreach program. Father Majstorovic and 16 volunteers will visit parishioners in the 5 boroughs, Long Island, and Westchester, personally appealing for restoration funds. “With a letter, they read it, think about it, and put it away,” said Father Majstorovic. “But people are more likely to do something with a visit. Being in front of them is the most efficient way. Our mission of the church is to maintain its meaning in [parishioners’] lives … If we have people in the church, then the money will be there.” Father Majstorovic and his team have a formidable task. Though there are 1,600 names on the church’s mailing list, fewer than 700 have contributed money. And with Sunday attendance at anywhere from 75 to 175 people, the regular donor pool is small. So finding the donors and convincing them to give is not as easy as preaching to the converted. “We’re like Ellis Island: People come through us, get stabilized, meeting their spouses, then they move on,” Luna said. “But I keep thinking someone’s going to hear our cry.” Saving Graces Historic Churches Desperately in Need of Funds Share Financial Woes as Well as Leaky Roofs 14 • NEW YORK RESIDENT The Week of July 5, 2004 • www. n ewyorkre s i d e n t . c o m • ( 2 1 2 ) 9 9 3 - 9 4 1 0 Set down at Broadway and 10th Street just 11 years earlier and 16 blocks south, Grace Church is anything but obscure. Part European cathedral, part fairy-tale confection, the elegant church has anchored its neighborhood as both a visual and cultural landmark. Like Santa Sava, Grace boasts an architectural pedigree. It was designed by James Renwick Jr., who later designed St. Patrick’s Cathedral and the Smithsonian Institution’s castle in Washington, DC. Built in 1844 in the Gothic Revival style, its 230-foot spire commands the sky, uninterrupted by surrounding buildings. Scaffolding, however, now obscures the church’s spindly beauty. A major restoration project was launched when architects discovered that a rusted anchor plate was causing the spire to lean six inches off its vertical. The plate holds the rod that runs through the connecting stones of the spire. Now a complex scaffolding holds the spire in place. And the spire is just the tip of the architectural iceberg: The decorative stonework around it is cracked, and the marble is deteriorating around the parapet, crockets, and other structural elements. Repairs to the spire, bell tower, and roof will cost an estimated $2.5 million — work that must be done to prevent further water damage to the church interior. “The history of architecture is 5,000 years of trying to keep the water out,” said Laurie Hammel, director of finance and development at Grace and herself a historic preservationist. Water leaks have disintegrated the plaster in the north- and southwest aisles, each segment requiring $25,000 of restoration. It’s costly to repair because water runs laterally, and the visible damage may be far from the source, says Hammel, who notes that past efforts at repair have largely involved “chasing the water down.” “You tend to repair what you can see,” she added. Even though the Municipal Art Society has designated the church as one of eight “structures to be protected at all cost,” Hammel says the church is not without its fundraising challenges. “It’s very difficult to separate the sacred from the secular,” Hammel said. “There is a view that public money ought not be spent on a sacred site. But this is an architecturally historic building that has been judged across the borders as a landmark and as a cultural resource.” But having the prestigious National Historic Landmark designation can also foster false impressions about the financial health of a site’s owners and their ability to maintain it. “Grace is in a unique position because of its landmark status, which now qualifies it for funding programs it previously was not eligible for,” said Ann Friedman, director of the New York Landmarks Conservancy’s Sacred Sites Program. “But because it’s an older, larger church with a large endowment, people assume the endowment will take care of restoration projects, and that’s not always true. “Though Santa Sava and Grace have different congregations and endowments, they both have good fundraising track records,” she continued. “And they both have great respect for the architectural history of their buildings. They are committed and are tackling their restorations by phases.” The convervancy has been assisting both churches since the 1990s. Fortunately, Grace Church is no stranger to innovative fundraising tactics. To help pay for the scaffolding and protective sidewalk covering — a $150,000 cost — the church gave businesses an opportunity to be real angels by leasing advertising space on the sidewalk shed. Leveraging its landmark status and fortuitous location, Grace could charge a premium for space on the novel billboard. Citigroup was the first to take the leap of faith with its “Live Richly” campaign. Even with assistance from the Robert A. Wilson endowment, Grace was still pressed for funds, so outgoing priest-in-charge, the Rev. David Rider, decided to put chunks of the church on the auction block. Ninety stones were removed from the top 25 feet of the spire during restoration, and those too damaged to be replaced were put up for auction. The carving from the very top of the spire fetched $6,500, and other small, grayish clumps sold in the $400s. The auction, organized by the church’s men’s group, netted $47,000 — less than what it costs to repair one bell tower wall. Grace’s new rector came on board July 1 and will be working with Hammel on new fundraising campaigns, which Hammel says will include reaching out to the local business community. One of the challenges, she said, is to emphasize the separation of church and state. “My sense is there’s a lot of unity in maintaining this as a New York City landmark,” she said. “It’s healthy to have people coming in and out of a church, even if they don’t go to church. And our approach is to not confuse mission with artifact.” More information about Santa Sava can be found at 212-242-9240 and stsavanyc.org. More on Grace Church can be found at 212-254-2000 and gracechurchnyc.org. E-mail responses to editor in chief Mark Rifkin at markr@resident.com. Grace Church: In better days back in the 1880s AP (212) 993-9410 • www. n ewyorkresident.com • NEW YORK RESIDENT The Week of July 5, 2004 • 15 ----------------------- May 4, 2003 Streetscapes/The Serbian Orthodox Cathedral of St. Sava on 25th Street; 1870's Ecclesiastical Village That Adjusted to Times By CHRISTOPHER GRAY A STRIKING hidden midblock complex on West 25th Street -- an 1855 Episcopal church, an 1866 clergy house and an 1870 school -- is partway into a restoration project likely to be long and expensive. Since the 1940's, it has been the Serbian Orthodox Cathedral of St. Sava, and even for native New Yorkers both the exterior and interior are likely to be a surprise. The present Trinity Church at Broadway and Wall Street was finished in 1846 -- just as the last of the parishioners within walking distance were moving farther uptown. To keep them in the fold, Trinity built a system of chapels in outlying areas. In 1851, Trinity adopted a plan by Richard Upjohn, who had designed the Wall Street church, for a through-block church on 25th Street just west of Broadway reaching up to 26th Street -- Trinity Chapel. A random sampling of 20 of the original pewholders indicates just why the main church felt it had to reach out; two lived in Westchester, three in old Trinity neighborhood, and the rest between 14th and 34th Streets, like the lawyer and diarist George Templeton Strong, who lived on 21st Street opposite Gramercy Park. The outside of Trinity Chapel, in neo-Gothic brownstone, was hardly unique. Indeed, the notoriously demanding critic Clarence Cook, writing in New York Quarterly in 1855, called it ''decidedly a failure,'' adding that ''its front is tame, its side elevation meager'' - but then he also panned Grace Church, at Eighth Street and Broadway. However, the addition of the tiny Clergy House at 16 West 26th Street (now the church office) in 1866 and the Trinity Chapel School at 13 West 25th (now a parish hall) in 1870 created a little ecclesiastical village that still surprises newcomers to the area, especially with the wide view running from 25th to 26th Streets. The church interior -- stretching almost 180 feet, much longer than the typical urban church -- was widely discussed. The New York Times praised the very slight outlining in red and other colors of the open truss work, saying ''the illuminated timbers of the roof form a perfect chef-d'oeuvre of architectural effect.'' The interior is faced with a creamy Caen stone, a limestone imported from France, making the interior as light as the exterior is dark. Small alcoves along the walls held open pews. The new Trinity Chapel became one of New York's most socially important churches -- Edith Jones had plenty of time to reflect on her imminent marriage as she walked down the long aisle to marry Edward R. Wharton in April 1885. She did not turn back, although she soon became disenchanted with her husband and developed her writing career around the turn of the century. An 1892 issue of a parish publication, the Trinity Record, reflected on the changes in architectural tastes over four decades. It noted that, prior to the early 1870's, Trinity Chapel had been quite plain, ''painfully guiltless of polychromatic effects,'' with the exception of the colored striping on the ceiling woodwork and the blue and gold cross-striping on columns supporting the trusses, which the congregation contemptuously called barber poles. But soon thereafter the chancel walls were given a very elaborate decorative treatment and other painted effects were added, apparently including the soft blue ceiling with gold stars -- the roof is perhaps 80 feet high, and in the soft haze of the interior the painted effects are so gentle they are hard to read. Fashion continued to move uptown and by the 1910's the side streets west of Madison Square were filling with loft buildings -- leaving the Trinity Chapel complex an oasis. Trinity Church decided to abandon its little outpost and The Times observed that ''no tears will be shed; it has never been considered a landmark,'' adding ''perhaps it is better to tear the building down than to build little additions to it and let the old church remain, battered and unsightly.'' Trinity Chapel remained open, and the Trinity parish thought enough of it to remove stained glass and other artwork in early 1942, during air raid concerns after Pearl Harbor. But later that year the parish put the chapel on the market, selling it in 1943 to members of the Serbian Orthodox Church, who established the old Trinity Chapel as the Cathedral of St. Sava, named after a 13th-century saint who became the first archbishop of Serbia. King Peter II, the exiled king of Yugoslavia, attended services here in the 1940's and never returned to his native land, which was still under Communist rule when he died in 1970. Later the Communist Party of the United States moved into 23 West 26th Street, and between 1964 and 1972 there were a half-dozen bombings at their building. In 1966 a powerful one blew out the stained-glass windows in the apse of St. Sava, and the cathedral replaced them with ones of a Byzantine design, more familiar to practitioners of the Eastern Orthodox religion. Two years later the exterior of the complex was designated a landmark. NOW the Cathedral of St. Sava is several years into a major restoration of its historic complex, especially the slate roofs on the cathedral and the church office. Under the direction of the building conservator William Stivale, the cathedral is partway done with the roof and pointing on the little office, facing 26th Street, and hoping to resume work on the cathedral soon. The parishioners have spent about $600,000 on initial stabilization, in part for reinforcement for the roof framing, which was starting to skew out of alignment due to water damage. The church now has about half of the $1.8 million necessary to finish just the roof of the entire church complex. And it needs it. The interior of the church is a spectacular antique -- a vast, high space, with all of the 19th-century decoration, hanging brass lamps, wall coverings, oak pews and polychromed tile floor almost untouched. But there are also wide stains of at least a dozen large leaks visible, some just large white blooms where water has seeped in, others where great patches of the Caen stone has been dissolved and fallen away. Whether by poverty or intent, the Serbs have been wonderful stewards of the building, making only the minimum changes necessary for their own worship, like the elaborate carved wooden iconostasis enclosing the former altar area. Serbian Orthodox services are usually conducted with the congregants standing, but at St. Sava they have left the Gothic-style pews, with their rich patina, in place. ''Here in America we've gotten a little bit relaxed,'' said the Rev. Djokan Majstorovic , dean of the cathedral, who was born in Bosnia, educated in Belgrade and was studying English in London, about to take up a post in Zagreb, when war broke out. He came to the United States seven years ago. ''Raising the money is quite difficult, but we have overcome so many disadvantages,'' Father Majstorovic said. The church has made its third application for a $400,000 grant from the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, and is hoping for success this time. Father Majstorovic added: ''Once people see the sincerity and honesty in our goals and efforts, they see the sincerity and honesty in it, they give; we are really advancing, we believe that God is helping us and overseeing us.'' Correction: May 11, 2003, Sunday The Streetscapes column last Sunday, about the Serbian Orthodox Cathedral of St. Sava -- built in the 19th century as Trinity Chapel -- misstated the location of another church criticized along with it by Clarence Cook, an architecture writer of the 1850's. That second church, Grace, is at Broadway and 10th Street, not Eighth Street. Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company |

|

|

links |

Special thanks to http://www.stsavanyc.org |