|

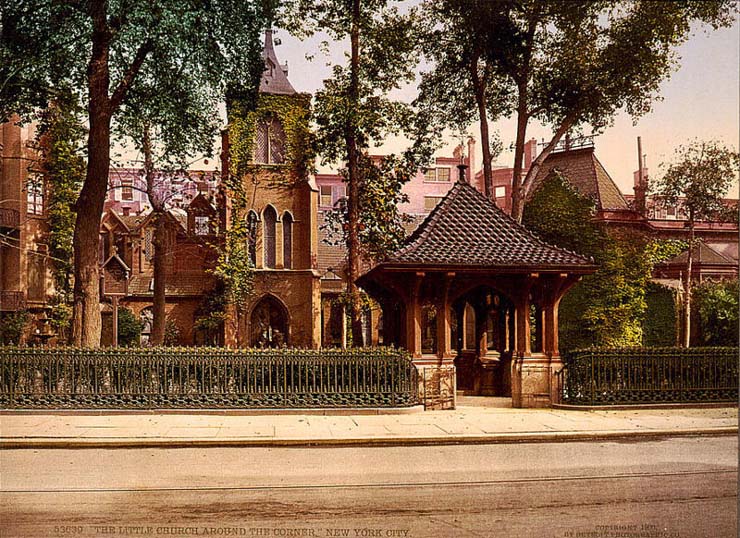

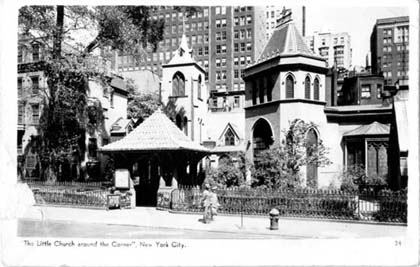

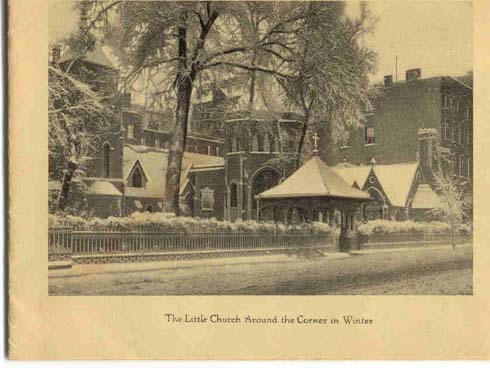

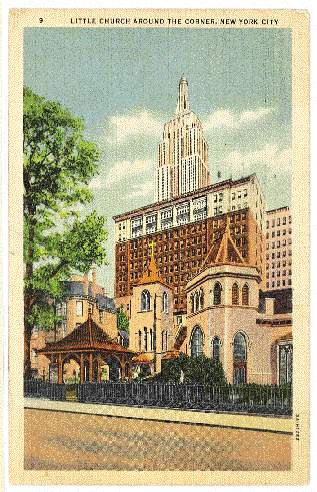

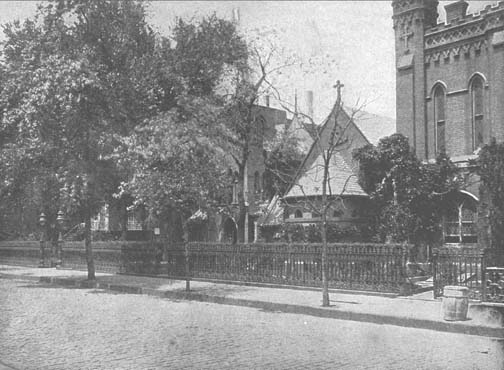

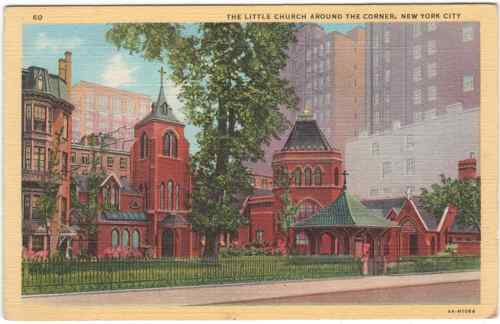

New York Architecture Images-Gramercy Park Transfiguration (Episcopal) - aka "THE LITTLE CHURCH AROUND THE CORNER" |

|

architect |

F.C.Withers et al. |

|

location |

One East 29th St. |

|

date |

1849-1926 |

|

style |

early English Neo-Gothic style |

|

construction |

brick, timber |

|

type |

Church |

|

|

|

|

|

|

images |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.jpg) |

|

|

The Church of the Transfiguration, more often known as The Little Church

Around the Corner, was founded in 1848 by the Rev. Dr. George Hendric

Houghton in New York City. The first services were held in a home at 48

East 29th street and in 1849 the new church was built and consecrated. Urban oasis Located at 1 East 29th Street,in the Murray Hill District, the church is set back from the street behind a garden creating a facsimile of the English countryside in midtown Manhattan and has long been an oasis for New Yorkers of all faiths who relax in the garden, pray in the chapel or enjoy free weekday concerts in the main church. It has also been known as the "wedding church" because of the popularity of the church for weddings. The “Little Church Around the Corner,” was founded in 1848 “to embrace all races and classes.” Designed in the early English Neo-Gothic style and with its quaint English Garden retains a picturesque quality of a true English parish church, despite being in sight of the Empire State Building. The church also features numerous and eclectically designed side chapels and a 14th Century stained glass window. Early years Transfiguration has been a leader of the Anglo-Catholic movement within the Episcopal Church from its founding. While this movement often is associated with elaborate worship, it also has stressed service to the poor and oppressed from its earliest days. Dr. Houghton built a congregation that cut across class and racial ines, sponsored bread lines to feed the hungry, worked vigorously for the abolition of slavery and harbored runaway slaves. In 1863, during the Civil War Draft Riots Houghton gave sanctuary to Negroes who were under attack. The rioters blamed slaves and freedmen for the war and the draft. Ties to the theater Actors were among the social outcasts whom Dr. Houghton befriended. In 1870 the rector of a nearby church refused to conduct funeral services for an actor named George Holland (the father of Joseph and Edmund Milton Holland {1}), but suggested that a "little church around the corner" probably would do "that sort of thing." Joseph Jefferson, a fellow actor who was trying to arrange Holland's burial, exclaimed "God bless the little church around the corner!" and the church began a long standing association with the theater. P.G. Wodehouse, when living in Greenwich Village as a young writer of novels and lyrics for musicals, married his wife Ethel at the Little Church in September 1914. Subsequently Wodehouse would set most of his fictionalised weddings at the church; and the hit musical Sally he wrote with Jerome Kern and Guy Bolton ended with the company singing, in tribute to the Bohemian congregation: "Oh dear little Church 'Round the Corner / Where so many lives have begun / Where folks without money / see nothing that's funny / In two living cheaper than one". Shakespearean Actor Sam Waterson, of the Law & Order TV Show fame was married here (for a second time). In 1923 the Episcopal Actors' Guild held its first meeting at Transfiguration. Such theatrical greats as Basil Rathbone, Tallulah Bankhead, Peggy Wood, Joan Fontaine, Rex Harrison and Charlton Heston have served as officers or council members of the guild. National Historic Landmark In 1973, The Little Church was designated a National Landmark and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in recognition of its position as a shrine of the American church and theater. Recent history The parish is currently under the rectorate of the Rt. Rev. Andrew St. John, formerly assistant bishop in the Anglican Diocese of Melbourne. St. John was named vicar on March 1, 2005 and called as rector on May 13, 2007. Music program The church has long been associated with a program of fine music. The Anglican tradition of a men and boys choir has been maintained with special music for concerts and summer services provided by a choir of mixed voices. In 1988 the Arnold Schwartz Memorial organ, a new tracker pipe organ was built and installed at the church by C. B. Fisk, Inc. Sunday |

|

|

A most confusing jumble of spaces and features, a long

low and internally rather dark building, with a Chinese-looking

lychgate, two |

|

Special thanks to

www.churchcrawler.co.uk

(British and international church architecture site) for generous

permission to use images and info. |

|

A Brief History of the Little Churchspecial thanks to http://www.littlechurch.org/--The Rev. Dr. George Hendric Houghton, Founder

|

|

The First Dr. Houghton On

the first Sunday in October 1848, George Hendric Houghton gathered a

band of twenty-four followers for a celebration of Holy Communion in the

parlor of the home of the Rev. Dr. Lawson Carter, an elderly priest, on

East Twenty-fourth Street. As Houghton's followers left this service by

the back door, they stepped into a road fortuitously called Love Lane.

None of those first worshipers could have imagined that they had just

attended the first service of the Church of the Transfiguration, later

to be celebrated as "The Little Church Around the Corner." It was even

more unlikely that they could have foreseen the rich church life, the

exciting ecclesiastical and secular history, and the enviable record of

loving service that they and their successors would extend to the people

of New York City - indeed to men and women from all over the globe. On

the first Sunday in October 1848, George Hendric Houghton gathered a

band of twenty-four followers for a celebration of Holy Communion in the

parlor of the home of the Rev. Dr. Lawson Carter, an elderly priest, on

East Twenty-fourth Street. As Houghton's followers left this service by

the back door, they stepped into a road fortuitously called Love Lane.

None of those first worshipers could have imagined that they had just

attended the first service of the Church of the Transfiguration, later

to be celebrated as "The Little Church Around the Corner." It was even

more unlikely that they could have foreseen the rich church life, the

exciting ecclesiastical and secular history, and the enviable record of

loving service that they and their successors would extend to the people

of New York City - indeed to men and women from all over the globe.

His long interest in the abolition of slavery led Dr. Houghton to found the first black Sunday school in New York City and to harbor runaway slaves as part of the Underground Railway, one stop on which was the basement of the church's rectory. During the Civil War, many recent European immigrants of the late 1850s and early 1860s were drafted against their will into the Union Army. They took out their rage and resentment on the blacks, whom the immigrants blamed for the war. Blacks were burned, hanged, and mutilated during the Draft Riots of July 1863. So well known as defender and friend was our courageous founder that a large number of black people who were beleaguered and threatened sought sanctuary in his church. Angry mobs trying to get at those who had found sanctuary within the church twice thronged the gates of the churchyard. Policemen on duty warned our founder that they could not insure protection from the mob. With firm resolution, George Houghton lifted the processional cross from its place in the church, walked out to face the rioters, held it before them, and said, "Stand back, you white devils; in the name of Christ, stand back!" With such courageous words, George Houghton held off the unruly mob, and those in the church remained safe for several more days, until the mob had been quelled and dispersed.

The regular cycle of liturgical prayer lay always at the heart of our founder's ministry. The Oxford Movement had restored the centrality of the Sunday celebration of the Holy Eucharist, and Dr. Houghton brought that focus to our church from its foundation. He had recited the daily offices since the beginning of his ministry. From 1880 onward a regular daily mass has been celebrated in our church. The sacrament of penance and absolution has always been made available and encouraged as an unfailing vehicle of God's reconciling grace.

During the 1880s and 1890s people from all social classes and races worshiped here as one family. Perhaps this comprehensive makeup of our congregation is the most valuable legacy we have received in addition to the tradition of regular eucharistic worship established during George Hendric Houghton's long rectorate. Late in 1896 our father founder became ill. He was seventy-seven years old and had been our rector for forty-nine years when, after a short period of confinement, he died on November 17, 1897.

|

|

The Second Dr. Houghton Before

his death, George Hendric Houghton made clear his wish that his

nephew George Clarke Houghton, a priest in Hoboken, New Jersey, should

succeed him. The younger Houghton's ministry was principally one of

enlargement and enrichment, based upon his uncle's solid foundation. The

Lady Chapel was a gift from George Clarke Houghton in memory of his

wife, Mary, who had died in 1902, after living only six years in this

parish. Before

his death, George Hendric Houghton made clear his wish that his

nephew George Clarke Houghton, a priest in Hoboken, New Jersey, should

succeed him. The younger Houghton's ministry was principally one of

enlargement and enrichment, based upon his uncle's solid foundation. The

Lady Chapel was a gift from George Clarke Houghton in memory of his

wife, Mary, who had died in 1902, after living only six years in this

parish.

The liturgical life of the parish grew apace, heavily influenced from the turn of the century until the early 1920s by the developing Anglo-Catholic movement in the American Episcopal Church. In 1920 our parish was host to the Second Anglo-Catholic Congress, a national conclave of like-minded members of the Episcopal Church that was inspired by the great Anglo-Catholic Congresses of the turn of the century in England.

The desire of young couples to be married in our church grew as the twentieth century matured. Our second rector set a standard of serious marriage instruction, grounded and nurtured in the Christian faith and life. Today, as throughout our history, our clergy prepare couples with care, in adherence to the marriage laws of the Episcopal Church, which enjoins the Christian values of lifelong marital fidelity and commitment to family life. One notable event during the rectorate of

the second Dr. Houghton was the funeral of O. Henry (William Sydney

Porter), when an incident occurred that embodied the sardonic twist of

many of the beloved short stories of this famous writer. O. Henry lived

at the Caledonia Hotel on Twenty-sixth Street and mentioned the church

in several stories, including "The Romance of the Busy Broker" and "The

Cop and the Anthem." When he died it was natural that his body should

lie in the church's St. Joseph of Arimathea mortuary chapel. His funeral

was scheduled for a June day in 1910 at eleven o'clock. After World War I many of the families resident in our geographical parish began to migrate uptown. New businesses moved into our neighborhood, and large urban office buildings were constructed in place of the old town houses that had lined the streets of the East Twenties and Thirties north of Madison Square.

|

|

What is the Church of the Transfiguration?R. William Franklin, Ph.D. The Church of the Transfiguration is one of the most famous parishes of the Episcopal Church in the United States, itself a part of the worldwide family of churches in communion with the Archbishop of Canterbury. Transfiguration is known throughout the country as "The Little Church Around the Corner," and for one hundred and fifty years it has been a very visible worshiping community in an urban setting that has welcomed all classes, all races, and particularly all those marginalized by society for whatever reason, as were actors and actresses, who had theretofore been on the fringes of both society and the Episcopal Church. The Church of the Transfiguration practiced this deliberate inclusivity for two reasons. First, it was among the earliest parochial outposts in the New World of the Catholic revival in the Anglican Communion. This revival began in England and was associated with the Oxford Movement, whose teachings first arrived on these shores in about 1839. In response to the Age of Revolution in England, which included the industrial revolution, democratic reform, and urbanization, the leaders of the Oxford Movement reasserted that the Churches of the Anglican Communion are part of the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church of Jesus Christ on earth. In this proclamation they looked in two directions: They looked backward to the primitive church of the persecuted and oppressed, gathered as a eucharistic community; this primitive model was to be a model for the modern church. And they looked up: The church to the Oxford Fathers is also a supernatural society, the body on earth of the risen Jesus, who through the Holy Spirit sanctifies men and women and makes saints. One of these Oxford Fathers, Edward Pusey, urged in particular that the Anglican Catholic revival should focus on modern cities, such as London and New York, rather than on areas of former population concentration and the picturesque countryside where the comfortable parishes were located. Second, this parish was the creation in 1848 of a man who not only successfully transferred Dr. Pusey's Oxford teaching to Manhattan, but had himself experienced life on the fringes of society. When George Houghton moved to New York City in 1834, he had to work fifteen hour days while still a student to help support his widowed mother. He was so poor after becoming rector of this parish that he lived in the sacristy of the church until a rectory was built, and even later Dr. Houghton supplemented his parochial income by teaching Hebrew at the General Theological Seminary for the meager sum of $500 a year. George Houghton concluded, on the basis of his own experience and Dr. Pusey's teaching, that some Episcopalians should build a spiritual home in this city of New York to which all would be welcomed. When no one came forward to build such a church, he realized that that builder and pioneer would have to be himself, and he announced his plan to establish a place "where the Church should be free to all, where charitable institutions for the afflicted of all sorts and conditions are made available for all." This ideal of Catholic inclusivity in the Episcopal Church, which this parish perhaps more than any other in America stood for in the nineteenth century, the welcoming of actors and actresses to sacraments and services for which it became well known, caused "The Little Church Around the Corner" to be immortalized throughout the nation. What is less well known is that in 1894, after fashion had begun to move up Fifth Avenue north of Twenty-ninth Street, the parish fell on hard times. The news spread in the theatrical world of New York City, and within a month elicited a tremendous financial response from Broadway in support of the Church of the Transfiguration, $3,000 more than was needed for the budget. In typical fashion, Dr. Houghton devoted the excess contributions to the needs of the sick and the poor, to the care of homeless children, and to establish a fund to bury from this church the penniless dead of the city whose families could not afford a proper funeral. Of the contributions of people of the theater to sustain the parish through the twentieth century, Dr. Houghton wrote:

As we end the twentieth century, we live at a moment when many despair in the face of the problems of the institutions, large and small, of the Church. Before such uncertainty the institutional history of the Church often seems "superficial and unworthy, absorbed in trivialities and rivalries," neglecting the deepest fears and longings of God's people. Yet the founding vision of this parish, wrought out of a time of Christian renewal a century and a half ago, which has sustained it from its early days, still speaks of faith in God's unquenchable desire for the wholeness and restoration of every man and woman in this city, and the record of nine generations who have come to "The Little Church Around the Corner" gives us hope that our church life is not doomed to ultimate frustration but may find its unimaginable fulfillment in the presence and in the joy of the One by whom we were made. The example of the founder and the forebears now beckons us forward to look at the future as the Apostle Paul looked at it, "confident that nothing can separate us from the love of God, constantly leaving the things that are behind, and stretching out toward the things which lie before us, toward the high calling of God in Christ Jesus."

|

|

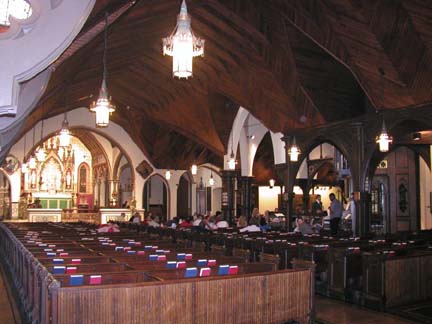

The Chancel Area As

one enters the church nave, the eye is at once drawn to the colorful

vision of the high altar and reredos. On either side of

the chancel arch are two Venetian mosaic rondels - the

Archangel Gabriel (on the left) announcing the birth of the Incarnate

Son of God to the Blessed Virgin Mary (on the right). Both figures point

the worshiper toward the sanctuary, where the high altar, with

its reredos depicting our Lord's Transfiguration, dominates the vista.

Together they represent a statement of the presence of Christ in and

with His church. In this initial view of the interior of our church, one

realizes the truth of the description of a Christian church as a roof

and walls that surround and protect a eucharistic altar. The two

stained-glass windows on either side of the high altar underscore this

point. They show angels censing the altar and the words: "Holy, holy,

holy, / Lord God of Sabaoth." As

one enters the church nave, the eye is at once drawn to the colorful

vision of the high altar and reredos. On either side of

the chancel arch are two Venetian mosaic rondels - the

Archangel Gabriel (on the left) announcing the birth of the Incarnate

Son of God to the Blessed Virgin Mary (on the right). Both figures point

the worshiper toward the sanctuary, where the high altar, with

its reredos depicting our Lord's Transfiguration, dominates the vista.

Together they represent a statement of the presence of Christ in and

with His church. In this initial view of the interior of our church, one

realizes the truth of the description of a Christian church as a roof

and walls that surround and protect a eucharistic altar. The two

stained-glass windows on either side of the high altar underscore this

point. They show angels censing the altar and the words: "Holy, holy,

holy, / Lord God of Sabaoth."

Frederick Clark Withers, an English Victorian Gothic Revival architect, designed the chancel, which he rebuilt, extended, and decorated in 1880 - 81. The handsomely carved sedilia and stalls in the presbytery of the church were designed by Henry Vaughn as choir stalls for the newly enlarged choir of the 1880s. These stalls were adapted to their present use as seats for the clergy and acolytes after the choir was returned to its earlier position in the church, between the south side of the nave and the south transept. The rich polychrome of the reredos and the sanctuary wall represents a relatively new effort to follow the principles of the Cambridge-Camden Society, founded in 1839, whose aims were to revive historically authentic Anglican worship and ceremonial, to restore medieval churches, and to see new churches built in the Gothic style and richly decorated so as to involve the senses as an aid to worship. To these ends, the society carried out extensive ecclesiological surveys of medieval churches in England and laid down its canon for a "model church" that would embody the society's tenets.

The elaborately wrought brass pulpit stands near the chancel on the northeast side of the nave and was designed by the most notable American architect of the early Gothic Revival, Richard Upjohn. The lectern on the south side responds elegantly to the pulpit. Edwin Booth, the distinguished actor, made the gift of a Bible for the lectern. From these two richly detailed church furnishings the Word of God is proclaimed and read. The Blessed George Hendric Houghton Chapel To

the south of the sanctuary lies the chapel dedicated in honor of our

founder, who was called in his own time " the first saint of the

American Church." The chapel contains a simple freestanding altar,

covered in festal seasons by a rich red-and-gold Jacobean frontal.

From the 1880s until 1987 this space was occupied by a large pipe organ.

The pipes of the lowest pedal stop of our present organ hang on the

south wall of this chapel. The large painting behind the altar is a

nineteenth-century copy of Domenichino's Communion of St. Jerome.

The seventeenth-century original hangs in the Vatican. To

the south of the sanctuary lies the chapel dedicated in honor of our

founder, who was called in his own time " the first saint of the

American Church." The chapel contains a simple freestanding altar,

covered in festal seasons by a rich red-and-gold Jacobean frontal.

From the 1880s until 1987 this space was occupied by a large pipe organ.

The pipes of the lowest pedal stop of our present organ hang on the

south wall of this chapel. The large painting behind the altar is a

nineteenth-century copy of Domenichino's Communion of St. Jerome.

The seventeenth-century original hangs in the Vatican.The TranseptThe south transept, which was built in 1854 and extended in the 1860s, houses a number of interesting objects and memorials, among them two sixteenth-century Flemish painted wood panels that ornament the front of the confessional box. They are side panels of a triptych, the central panel of which is not in the church's possession. The left-hand panel represents St-Denis, patron saint of Paris, after his martyrdom; the right-hand panel, the Virgin and Child. In the foreground of both panels is, presumably, a family portrait of the donors. Other paintings in the transept, as well as in the nave and chapels, are mostly nineteenth-century copies of older paintings.To the south of the confessional box stands the columbarium, which was installed in 1991 to contain the funerary ashes of parishioners and friends of the parish who wish to be buried in our church. Before the columbarium stands a large icon of the Resurrection of Christ, known in the Eastern Church as the Anastasis. This icon provides a bold statement of the Christian resurrection hope. It was executed by Vladislav Andrejev, dedicated on Easter Day 1995, and provides a shrine for prayer for the faithful departed. The icon was given by Father and Mrs. Catir in memory of their parents. A pair of unusual doors of painted glass and brass are situated farther along the transept east wall. Mrs. Janos Schultz, mother of former chorister Christopher Schultz, gave them in 1972, in memory of her first husband, Ernest Schelling (1876 - 1939), the distinguished pianist, conductor, and composer. Every Sunday the choir passes through these doors, which show angels playing musical instruments and which bear the words: "Music is well said to be the speech of angels." At the south end of the transept stands a richly carved and polychromed shrine with a figure of the Madonna and Child designed by the noted Gothic Revival architect Ralph Adams Cram. This shrine was installed here in the1920s, when the baptismal font was moved to its present location between the Chapel of the Holy Family and the Lady Chapel. The font had originally been located directly in front of the altar rail in the sanctuary. The two windows flanking the Madonna Shrine set forth baptismal themes, in keeping with the former use of the alcove as a baptistery. The one on the right is a testament to our founder's Christian stance on racial equality. It is called the "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" window because the top panel depicts the scene of the Ethiopian eunuch in his lavish chariot, talking with St. Philip. The central panel shows him subsequently being baptized by St. Philip. (See Acts 8:26 - 39 for the account.) The window memorializes a black couple, George and Elizabeth Wilson (he a former slave and she a freewoman), as "Sometime doorkeepers in this House of the Lord," a paraphrase of Psalm 84:10. The Wilsons worked with the first Dr. Houghton for thirty years after the Draft Riots of 1863. On the west wall of the transept there are two large, important windows. On the left, is the Edwin Booth window by John La Farge, which portrays the noted actor in the role of Hamlet, which was given as a memorial by members of the Players Club in 1898. Booth was a member of this parish and the founder of the Players Club, which was formed, partly in reparation for his brother John Wilkes Booth's assassination of Lincoln, to provide a place where actors and nonactors could meet. The club is located just a few blocks downtown, on Gramercy Park. On the right, in the style of La Farge, is the King David window - also known as the "Jeweled Window" because of the richly colored bits of glass simulating rubies and sapphires - which portrays the importance of music in God's creative plan. It is a memorial to Joseph W. Drexel (1831 - 1888). Together the two windows present a fitting tribute to two of the performing arts, members of which have been among the worshipers in our church for more than a century. Just around the corner from the King David window a blaze of painted glazing that vaguely resembles a collection of Victorian valentines intrigues the viewer. These windows in fact contain the psalms of the Office of Compline, the last monastic office of the day. The design of the Compline windows was adapted from paintings on parchment executed by Caroline Graves Anthon Houghton, the wife of our founder, and the windows were given as a memorial to her after her death in 1871. A crèche is placed in the area in front of them during Christmastide. Sarah Morgridge refurbished the crèche figures in the early 1990s, when her son, Dugan, was a chorister. The Arnold Schwartz Memorial Organ In

1980, Mrs. Arnold Schwartz made it possible for this church to

complete and make final its plans to commission one of the finest pipe

organs recently built for a New York church. Designed and constructed by

the C. B. Fisk organ company of Gloucester, Massachusetts, the organ

(Opus 92) was finished and dedicated on April 10, 1988. It is a tracker,

or mechanical-action, organ, designed largely in the eighteenth-century

North German tonal style but with an extensive nineteenth-century French

Cavaillé-Coll type swell division. This union of two historic

organ-building styles makes for great versatility in performing the

organ literature of all periods, as well as producing an instrument

eminently fit to present and accompany traditional Anglican liturgical

music. The organ case was designed by Charles Nazarian, a consultant to

C. B. Fisk, and executed largely in the Fisk workshop in Gloucester

along with the rest of the instrument. The late Daniel Maloney, a

distinguished artist and onetime vestryman of the church, designed and

carved the twelve quatrefoil bas-relief plaques set around three

sides of the lower portion of the case. The organ and choir stalls rest

on a platform of Brazilian cherry, a hardwood that increases musical

resonance. In

1980, Mrs. Arnold Schwartz made it possible for this church to

complete and make final its plans to commission one of the finest pipe

organs recently built for a New York church. Designed and constructed by

the C. B. Fisk organ company of Gloucester, Massachusetts, the organ

(Opus 92) was finished and dedicated on April 10, 1988. It is a tracker,

or mechanical-action, organ, designed largely in the eighteenth-century

North German tonal style but with an extensive nineteenth-century French

Cavaillé-Coll type swell division. This union of two historic

organ-building styles makes for great versatility in performing the

organ literature of all periods, as well as producing an instrument

eminently fit to present and accompany traditional Anglican liturgical

music. The organ case was designed by Charles Nazarian, a consultant to

C. B. Fisk, and executed largely in the Fisk workshop in Gloucester

along with the rest of the instrument. The late Daniel Maloney, a

distinguished artist and onetime vestryman of the church, designed and

carved the twelve quatrefoil bas-relief plaques set around three

sides of the lower portion of the case. The organ and choir stalls rest

on a platform of Brazilian cherry, a hardwood that increases musical

resonance.

St. Joseph of Arimathea Chapel and Surrounding AreaThis requiem chapel, which was designed by George Clarke Houghton in 1908 in memory of the founder, lies to the south of and behind the organ and choir area. Its entrance is graced by a marvelously carved and polychromed angel screen that is pierced by an arch in the center of which is a gate, the finest piece of wrought-iron craftsmanship in the church.Within the octagonal chapel is the St. Joseph altar, over which is the painted-glass Transfiguration window. This window was over the high altar until 1881, when the east end of the church was enlarged and enriched. The ceiling of the St. Joseph chapel presents a lively vision of the heavenly host, painted on canvas panels fitted between the ribs of the plaster vault. St. Joseph of Arimathea was the rich man who gave his tomb for the burial of Christ's body after He was crucified. Today the chapel is used as a place where the coffin of a deceased person may lie before the day of the funeral, and friends and loved ones may come and pray. To the right of the St. Joseph chapel is the statue of the Singing Boy, made in 1871 in Rome by an American artist. When the open songbook he is holding is lightly touched, it gives forth melodic notes. Next to the statue is the Houghton window, depicting George Clarke Houghton celebrating Solemn Mass at the high altar at the Second Anglo-Catholic Congress, which was held in the church in 1920. A gift of Dr. Houghton's daughter, it was dedicated in 1926.

The South Aisle of the Nave Turning

left into the south aisle of the nave, one can see several windows.

The most important is the Joseph Jefferson window, which is a

memorial to the renowned actor who pronounced his benediction on our

church, thus bestowing upon it its popular name, "The Little Church

Around the Corner." For more than forty years, Jefferson starred in the

role of Rip Van Winkle, and the right-hand panel of the window shows

Jefferson as Rip, bringing the shroud-wrapped body of his actor friend

to the church. The left-hand panel shows the image of the risen Lord,

with nail wounds in his hands and feet, standing by our lych-gate and

greeting Jefferson as he escorts George Holland's body to his burial

service. In panels above and beneath the two main window lights are

scenes from Washington Irving's story of Rip Van Winkle. This window was

given by the Episcopal Actors' Guild and unveiled by the actor's

great-granddaughter, Lauretta Jefferson Corlett, on February 20, 1925,

the ninety-sixth anniversary of Joseph Jefferson's birth. Turning

left into the south aisle of the nave, one can see several windows.

The most important is the Joseph Jefferson window, which is a

memorial to the renowned actor who pronounced his benediction on our

church, thus bestowing upon it its popular name, "The Little Church

Around the Corner." For more than forty years, Jefferson starred in the

role of Rip Van Winkle, and the right-hand panel of the window shows

Jefferson as Rip, bringing the shroud-wrapped body of his actor friend

to the church. The left-hand panel shows the image of the risen Lord,

with nail wounds in his hands and feet, standing by our lych-gate and

greeting Jefferson as he escorts George Holland's body to his burial

service. In panels above and beneath the two main window lights are

scenes from Washington Irving's story of Rip Van Winkle. This window was

given by the Episcopal Actors' Guild and unveiled by the actor's

great-granddaughter, Lauretta Jefferson Corlett, on February 20, 1925,

the ninety-sixth anniversary of Joseph Jefferson's birth.

Throughout the church are dormer windows, located above the main windows. One that is of particular interest to parishioners and visitors alike is The Golden Rule window over the rear of the south aisle, which was given in 1933 in honor of Dr. Ray's tenth anniversary as rector. The theme is the Golden Rule as it has been interpreted by the great world religions, culminating in the Christian concept of "Love Triumphant" shown in the central medallion. This medallion depicts a crowned heart with a figure denoting Light (on the left) and another denoting Prayer (on the right). Medallion symbols down the left side represent (according to 1930s sources) the Persian religion by the palm-leaf pattern, the Islamic by a water jug, the Buddhist by the ancient fylfot cross, and the Egyptian by the lotus. (The fylfot cross, or swastika, is one of the most common variations of the non-Christian cross, and it appears in many ancient cultures.) Down the right side the Hindu religion is symbolized by the Tree of Life, the Roman by the dolphin, the Hebrew by the seven-branched menorah, and the Chinese by the cloud representing heaven. The North Aisle of the NaveThe Stations of the Cross, which begin at the east end of the north aisle, continue down that aisle, and conclude on the south wall of the nave, were given by Mrs. Franklin Delano (the former Laura Astor), a devout member of the parish and the great-aunt of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The paintings are of antique provenance, probably late eighteenth century, and were acquired from a chapel in Rome.A series of stained-glass windows and bronze memorial tablets along the wall of the north aisle of the nave pay tribute to members of the theater in particular, but to people in other walks of life as well. Among those memorialized on the bronze tablets are: the Benét family, Will Rogers, P. G. Wodehouse, Walter Edmund Bentley, Cornelia Otis Skinner, and Vinton Freedley. Two actors memorialized in stained glass are: Montague, a matinee idol of the 1870s, and John Drew. The St. Alban window and the St. Augustine window show the first English Christian martyr and the first Archbishop of Canterbury, respectively.

The NarthexThe narthex and chapel screens, which separate the nave of the church from the Chapel of the Holy Family, were dedicated on New Year's Day 1928. The design was inspired by the rood screen at St. Giles', Lord Shaftesbury's chapel at Wimbourne, in the south of England. This memorial to Elijah P. Smith, a parishioner for over fifty years and longtime senior warden, was given by his sister, Mrs. Eleanor de Forest Boteler. Wilfred E. Anthony was the architect of the memorial. The figures in the Crucifixion group (above the archway) and the saints (on the opposite wall of the narthex) were made by the celebrated woodcarvers of Oberammergau, Germany.The Peace Shrine, a statue of our Lord designed after the famous Christus Consolator by Thorwaldsen, was dedicated on Armistice Day in 1942 by Dr. J. H. Randolph Ray. It was originally called the Victory Shrine and stood in the alcove of the Compline Windows but now serves here as a focus for the devotions of many who visit the church to offer prayers. Chapel of the Holy Family This

portion of the church is part of the original building and was first

used as a parish schoolroom for boys. In 1852, as the congregation

increased, a gable-windowed second story was added, and the school moved

upstairs. Later the second story became the guild hall and national

headquarters for the Episcopal Actors' Guild of America. This

portion of the church is part of the original building and was first

used as a parish schoolroom for boys. In 1852, as the congregation

increased, a gable-windowed second story was added, and the school moved

upstairs. Later the second story became the guild hall and national

headquarters for the Episcopal Actors' Guild of America.

In 1926 the Chapel of the Holy Family, also known as the "Brides' Chapel," was reconstructed and designated as a memorial to the first Dr. Houghton. Again, in 1940, the chapel was extensively redecorated, this time for Dr. Ray's seventeenth anniversary. New pews were installed, and the walls and ceiling of the chapel were redecorated and paneled in oak. The eight windows on the north wall are a memorial to the first Dr. Houghton and were given by his nephew and successor. The upper group of four lights depict scenes from the life of Christ: the Nativity, the boy Jesus in the Temple, at his baptism, and at prayer in Gethsemane. The lower group of eight lights illustrates the Beatitudes, in fitting tribute to the saintly life of the church's founder. The north wall also has a bronze memorial tablet to the memory of the second rector, George Clarke Houghton. The famous Brides' Altar was blessed on Foundation Day in 1926 and is so called because the funds for it were contributed by hundreds of couples joined in holy matrimony here. The tabernacle door of the altar is adorned with jewels contributed by brides, a custom of the day. Tens of thousands of marriages have taken place before this altar.

In the southwest corner of the chapel stands a charming white marble statue of the Madonna and Child by the noted English sculptor Richard Westmacott, R.A., who also did the portico sculptures at Buckingham Palace, celebrating the battles of Trafalgar and Waterloo. Around to the south side, in an arched recessed area that forms a baptistery, there is a small plaque in memory of the English actress Gertrude Lawrence. On the left side of the baptistery is the entrance to the Lady Chapel, or the Chapel of the Blessed Virgin Mary. This tiny chapel, lovingly built in 1906 by the Rev. Dr. George Clarke Houghton as a memorial to his wife, Mary Creemer Pirsson Houghton, is separated from the Chapel of the Holy Family by three double doors of stained glass, which may be folded open. These are balanced by three arched windows in the south wall that show, left to right, Raphael's Madonna del Granduca, the church's high altar and rood wall (painting on glass), and Botticelli's Virgin and Child. The entire Lady Chapel is in the English Middle Pointed Gothic style, with the high-pointed arch in oak over the window and door openings as well as the altar recess.

|

|

The Church in Modern Times After

the death of George Clarke Houghton in 1923, the Very Rev. J. H.

Randolph Ray, the Dean of St. Matthew's Cathedral in Dallas, was

called to be our third rector. Dr. Ray had been a student at the General

Theological Seminary as well as curate at Zion and St. Timothy, a West

Side parish, before he went to Dallas. His wife, Mary Elmendorf Watson,

was the granddaughter of the Very Rev. Dr. Eugene A. Hoffman, one of the

most notable deans of the General Theological Seminary. The new rector

had a personal interest in people of the theater. After

the death of George Clarke Houghton in 1923, the Very Rev. J. H.

Randolph Ray, the Dean of St. Matthew's Cathedral in Dallas, was

called to be our third rector. Dr. Ray had been a student at the General

Theological Seminary as well as curate at Zion and St. Timothy, a West

Side parish, before he went to Dallas. His wife, Mary Elmendorf Watson,

was the granddaughter of the Very Rev. Dr. Eugene A. Hoffman, one of the

most notable deans of the General Theological Seminary. The new rector

had a personal interest in people of the theater.

The historic shrine ministry of our church to members of the theatrical profession, as well as to couples seeking Christian marriage, had increased during the twenty-five year rectorate of George Clarke Houghton. Dr. Ray seemed admirably prepared to take advantage of the increasing urban nature of our parish by further developing our theater and marriage ministries, and that is what he did. At the same time our third rector popularized our nickname, "The Little Church Around the Corner." In 1943, during World War II, the number of weddings in our church reached a peak of 2,900 marriages performed in one year. Every Saturday - sometimes on weekdays as well during this period when servicemen in vast numbers were being posted overseas - couples would line up in the church garden to await their turn to be married. Shortly after his arrival in 1923, Dr. Ray joined with the Rev. Walter Bentley and Deaconess Jane Hall to found the Episcopal Actors' Guild of America, an association formed both to foster the work of the church among people of the theater and to express the needs of theater people to the church. Walter Bentley, a priest who had been a Shakespearian actor, had founded the Actors' Church Alliance in 1892. Deaconess Jane Hall had established the Rehearsal Club, a residence for young actresses newly arrived in New York City. It seemed natural for the Church of the Transfiguration to become the home of the organization formed to link church and theater. J. H. Randolph Ray was made the Actors' Guild's first warden by virtue of his office as rector of our church, and all succeeding rectors have been ex officio wardens of the guild ever since.

Even as Dr. Ray carried on his extensive work with people of the theater, he also reached out in response to wider social needs brought on by the Great Depression. In 1930, beneath the lych-gate of our church, he organized a breadline that distributed food to hungry people, even as his two predecessors had done before him in times of economic crisis. The breadline usually extended over to and up Madison Avenue and then back toward Fifth Avenue on Thirtieth Street. In consultation with Dr. Ray, Heywood Broun, along with Mrs. William Randolph Hearst and Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt, set up an employment bureau in a nearby brownstone. The bureau was designed to help the men in the breadline prepare to get a job by providing facilities for showering, before receiving a new ten-dollar suit, and by doing whatever else was necessary to make them employable.

In 1958, having reached the recently mandated retirement age of seventy-two, J. H. Randolph Ray retired. He died in 1963. The Rev. Orin A. Griesmyer was soon called to be our fourth rector. For twenty-one summers prior to his call, Father Griesmyer had acted as supply priest while Dr. Ray was on vacation. In consequence, the fourth rector was familiar with our life and work when he was called to lead this parish. Father Griesmyer saw the need for a more fully equipped parish house. As a result of his leadership, the parish replaced the century-old brownstone with a modern structure for parish activities. It was completed in 1963. Fifteen years later, we found we could have used an even bigger building.

As have all of our rectors, Father Griesmyer practiced and taught the full faith of the universal Catholic Church, maintaining the eucharistic ministry of Sunday and daily masses.

Father Griesmyer's thirteen years as rector of our church came to a close with his retirement in 1971. He is now rector emeritus and lives in St. Petersburg, Florida, with his wife Doris.

Many visitors, as well as regular parishioners, appreciate the beauty and dignity of worship at Transfiguration, which is enhanced by the singing of our fine choir of boys and men. To insure the continuance of this choir, the Anthony J. Mercede Choir Scholarship Fund was founded in memory of our devoted junior warden and treasurer after his death in 1985. Many organists have said that our new organ (the Arnold Schwartz Memorial Organ, dedicated in 1988) is the finest in New York City, and the story of how it came to be is worth telling. The need for a new organ had been increasingly evident in the 1960s and 1970s. The parish did not have the resources to purchase a new instrument, but that did not stop Father Catir from praying every day for a solution to the organ problem. He did this for seven years, starting in 1973, during his daily intercessions after Morning Prayer. His faith and perseverance were rewarded in due time.

After further prayer for guidance, she called Father Catir to inquire into the possibility of making a gift to enable the church to purchase a pipe organ of distinction and character. In the end, Marie Schwartz pledged a gift that would triple the then current size of the organ fund. With gratitude the vestry unanimously accepted Mrs. Schwartz's generous gift and agreed to name the new instrument in memory of her late husband, Arnold Schwartz, who had been a philanthropist himself. From the day Mrs. Schwartz first saw the organ appeal until the evening on which the vestry thankfully accepted her gift, one week had elapsed.

Father Catir has maintained and added to the church's theater connections during his years as rector. He nurtured and helped found the Joseph Jefferson Theater Company, which as an off-off-Broadway company performed regularly from 1971 to 1978 in the church transept. Further productions continue to be performed on occasion in the church, and the top floor of the rectory was for many years a hostel for acting students.

Finally, social outreach and inclusivity have continued to be part of our parish. Since 1971 the Murray Hill SRO Project for Older People has ministered to the needs of the elderly in the neighborhood. Most of our frail elderly people live in single room occupancy hotels and have little contact with other people except through our special program. They breakfast and lunch in our parish hall, and special holiday celebrations are made possible by members of our parish. Medical, financial, and social services are available to the men and women who attend the program. In order to expand its mission, the parish reinstituted a Sunday school in the 1970s. It sought to work with homeless families housed in nearby welfare hotels in the years 1985 - 90. In 1993 we welcomed the Korean-American Episcopal Congregation to worship here and so have extended our mission in yet another direction.

To celebrate our 150th anniversary in 1998, our clergy, staff, and loyal parishioners continue to work to build a community whose longevity and dedication to service will carry our parish into the twenty-first century and the third millennium of Christianity. The parish hopes to raise $3,000,000 - that is, $10,000 in thanksgiving for each of its past 150 years and $10,000 for each of its next 150 years - so that we may continue our work as both parish church and shrine in the heart of New York City.

|

|

Rambling Reflections on Religious Pluralismby T. Peter Park tpeterpark@erols.com There's a little church around the corner that will (or won't) do or teach this or that. That's one of the strengths--but some would rather say, weaknesses--of American (and modern Western) religious freedom and pluralism. A week ago, I worshipped in the original "Little Church Around the Corner" in New York, while visiting the city to help a friend celebrate her birthday. Arriving in the city early, I attended a 5:30 Mass at the Church of the Transfiguration, the "Little Church Around the Corner," on East 29th Street between Fifth and Madison Avenues. The Church of the Transfiguration is an Anglo-Catholic Episcopal church, founded by the Rev. Dr. George Hendric Houghton in 1848. As a church of the Anglo-Catholic movement within the Episcopal Church, Transfiguration is noted for its elaborate, dignified worship, but also for its long tradition of service to the poor and oppressed, and devotion to social justice. It is also famous for its long identification as a special church for actors--which accounts for its nickname as the "Little Church Around the Corner." Actors, along with Blacks, were among the social outcasts whom Transfiguration and Fr. Houghton befriended in the 19th century. In 1870, the famous actor Joseph Jefferson (1829-1905) requested a funeral at another midtown New York Episcopal Church for his actor friend George Holland (1791-1870). Hearing that Holland had been an actor, the rector refused, acting on the widespread 19th century view of actors as dissolute, disreputable, immoral folk. However, the rector told the stunned Jefferson that "There is a little church around the corner," meaning Transfiguration, that would probably do "that sort of thing." Jefferson responded, "God bless the little church around the corner." And indeed Fr. Houghton, who had made Transfiguration a center for feeding the hungry, anti- slavery agitation, harboring runaway slaves, and giving sanctuary to Blacks during the 1863 Civil War draft riots, performed the funeral without question. Across the country, newspapers reported the incident. For actors throughout America, the "Little Church" became a spiritual haven. Many leading actors and actresses, including Edwin Booth, began worshipping there. Booth's own funeral took place at the "Little Church" in 1893. George Holland's funeral and Fr. Houghton's generosity popularized the phrase "little church around the corner." New York's Church of the Transfiguration was the "little church around the corner" where "that sort of thing" would be done for an actor's funeral in 1870. These days, in most communities in the United States and most other industrial Western countries, there is usually a little church around the corner--somewhere in one's city or town, within a few minutes' walking or driving distance--where "that sort of thing" is done (or not done). "That sort of thing" probably would not refer to marrying or burying actors these days. Nowadays, it may rather mean accepting and welcoming (or rather not welcoming) divorcees, single parents, gays, or lesbians, ordaining (or not ordaining) women or "out" and non-celibate gays or lesbians to the priesthood or ministry, re-marrying (or refusing to re-marry) the divorced, allowing (or not allowing) members of other denominations to receive Holy Communion, encouraging (or forbidding) the use of Oriental meditation practices, playing plain-chant and the music of Byrd, Purcell, Tallis, Bach, Händel, and Ralph Vaughan Williams, or happy-slappy praise-songs projected on overhead transparencies, burning or not burning incense, denying (or affirming) the literal physical Resurrection of Christ, his Virgin Birth, or the eternity of Hell, etc. Without giving up one's Christian (or Jewish) identification, one can simply go to the little church (or big cathedral or little synagogue) around the corner (or 5 blocks away) if one cannot go along with what one's own priest, pastor, or rabbi says. Except in the smallest hamlets these days, there's usually a little church around the corner (or 10 blocks away, or in the next suburb) to accept or oppose evolution, support or reject the ordination of women, preach theological liberalism or fundamentalism, bless or denounce same-sex unions, re-marry or refuse to re-marry divorcees, endorse or denounce contraception, burn or not burn incense, play Purcell, Byrd, Tallis, Vaughan Williams, and Gregorian chants or slappy-happy overhead-projected praise-songs, endorse or disparage pentecostal or practices like tongue-speaking. The little church around the corner or a mile down the road may be a more liberal or conservative parish of one's own denomination, or it may be a church of another, more liberal or conservative, denomination. Even in the officially monolithic Roman Catholic Church, one can find priests who dutifully perform modern vernacular masses or defiantly celebrate pre-Vatican II Latin masses, who enthusiastically endorse or scornfully ignore miraculous Marian apparitions and shrines like Lourdes, Fátima, and Medjugorje, encourage or disparage Pentecostal-like "charismatic" practices, and passionately proclaim or discreetly downplay and sidestep official Catholic stands on abortion, contraception, divorce-and-remarriage, and homosexuality. By moving over to a little church around the corner or down the road these days, you can find a theology, moral code, and liturgy more to your own taste or convictions than those of your parents' church, without bearing the stigma among your pew-neighbors of being in their eyes a heathen or a fanatic, an agnostic or a holy-roller, an infidel or a reactionary, a puritan or a libertine. This is one of the strengths of modern American (and general modern Western) religious pluralism--or, as some religious conservatives might rather say, one of its weaknesses. It has helped make modern Christianity peaceful and tolerant, with no interest in starting crusades, jihâds, religious wars, or inquisitions. It may also be criticized for encouraging religious indifferentism, for promoting a "consumerist" or "cafeteria" attitude to religion and a "different strokes for different folks," "we all worship the same God in different ways" view of theological and moral differences. Believers passionately devoted to the truth of a particular theology and morality, and the error of others, may blame the abundance of "little churches around the corner" for encouraging the belief that different theologies and moralities are not true nor false, not in conformity nor contradiction to God's will, not reflections nor distortions of "how things really are out there" in the spiritual world, but rather simply express different temperamental and cultural preferences reflecting different personality types, different class, ethnic, educational, and cultural backgrounds, and different genders or sexualities. Churchgoers may agree in the abstract that there is truth and error in religion, that some theologies and moralities are more true than others--but they no longer care deeply and passionately about this. They no longer think about it in their daily lives or their relationships with friends, neighbors, classmates, and co-workers. They no longer seriously believe that some friend, classmate, or neighbor will burn forever in Hell for belonging to the wrong church, expressing the wrong religious views, or indulging in the wrong sexual behavior. They find it perfectly normal, natural, and reasonable for individuals to choose the church, theology, and morality most congenial, comfortable, and natural for a person of their class, sexuality, educational level, cultural tastes, and general "life-style." All this reflects the individualistic ethos of modern Westerm industrial societies, especially the United States. We are a society of social, cultural, and religious walkers, accustomed to "voting with our feet." Our "little church around the corner" approach to religion harmonizes well with the popular wisdom of 20th century secular books of self-help advice like Bertrand Russell's The Conquest of Happiness (1930) and Wayne Dyer's Your Erroneous Zones (1976, 1993). It may sound odd to bring up a militant agnostic like Russell in connection with religious diversity. However, his stress on sympathetic associates in The Conquest of Happiness is in fact quite relevant to the sociology and psychology of religious pluralism. For "almost everybody," he felt, "sympathetic surroundings are necessary to happiness (Bertrand Russell, The Conquest of Happiness [New York: Horace Liveright, Inc., 1930; New York: The Hearst Corporation, Avon Book Division, n.d.], p. 83). Because of "differences of outlook" from his family or community, "a person of given tastes and convictions" may "find himself practically an outcast while he lives in one set," although "in another set he would be accepted as an entirely ordinary human being" A young man or woman "catches ideas that are in the air," but then "finds that these ideas are anathema" in his or her "particular milieu." It "seems to the young as if the only milieu with which they are acquainted were representative of the whole world." They "can scarcely believe that in another place or another set the views which they dare not avow for being thought utterly perverse"are "the ordinary commonplaces of the age." Young people thus suffer much "unnecessary misery, sometimes only in youth, but not infrequently throughout life." This "isolation" is "not only a source of pain," but "also causes a great dissipation of energy in the unnecessary task of maintaining mental independence against hostile surroundings"( The Conquest of Happiness, pp. 82-83).When "such young people go to a university," they may find "congenial souls" and "enjoy a few years of great happiness." Also, an intelligent man or woman living in a city like London or New York can "generally find some congenial set in which it is not necessary to practice any constraint or hypocrisy" (The Conquest of Happiness, p. 84). Russell was mostly thinking of religion (plus politics and sexual ethics) in his discussion of people out of sympathy with their family or community who would be much happier if surrounded by a more congenial circle of people. Russell himself largely thought in terms of a simple dichotomy of ultra-conservative near-fundamentalist religionists versus outspoken agnostics or atheists like himself. However, his observations about sympathetic versus unsympathetic social circles are applicable as well to different shadings of religious belief among believers themselves, between religious fundamentalists versus liberals. Many young people grow up in fundamentalist or ultra-conservative Catholic, Protestant, Episcopalian, or Jewish families, but find themselves out of sympathy with the hard-shell beliefs of their families or their home-town church or synagogue. They may be skeptical of their parents', pastor's; or rabbi's theology, or they may chafe at the strait-laced life- style, or they may feel tremendous pain at discovering themselves to be gay or lesbian but condemned as sinners and perverts destined to burn in Hell unless they get "cured." In many cases, they abandon their religion altogether. In other cases, however, they decide to keep their basic Christian or Jewish identification, but choose a more liberal version. They may move to the more liberal wing of their own denomination, or they may join a more liberal denomination. In either case, they see themselves as leaving a "sadly up-tight and out-of-it" religious community where they are "outcasts" with "utterly perverse" views and life-styles for an "enlightened" one where they are "entirely ordinary human beings" holding the "ordinary commonplaces of the age." Bertrand Russell was one of the 20th century's leading philosophers, and a celebrated, passionate intellectual crusader for pacifism, nuclear disarmament, socialism, educational reform, freedom of thought and speech, and "free love."Wayne Dyer is a more "lowbrow" pop-psychologist, an author of popular self-help books with no interest in any political or social "causes" nor in flamboyantly eccentric Bohemian nonconformity. However, Dyer's a-political, un-ideological, un-Utopian recipe for personal happiness and peace of mind echoes Russell's in its advocacy of quietly walking away from unnecessary, unproductive conflict with people whose values, beliefs, interests, or agendas are opposed to your own. Dyer preached this "walking away" recipe most explicitly in his 1976 best- seller, Your Erroneous Zones [Wayne W. Dyer, Your Erroneous Zones (New York:Funk & Wagnalls, 1976; HarperCollins, "Harper Paperbacks," 1993] Personal happiness and social progress, for Dyer, depended on individuals who "reject convention and fashion their own worlds," who "resist enculturation and the many pressures to conform." To "function fully" as a free, happy, effective human being, "resistance to enculturation "was "almost a given," though one may be "viewed by some as insubordinate," "seen as different," "labeled selfish or rebellious," and "at times be ostracized." This has "nothing to do with anarchy." Dyer wanted not to "destroy society," but only to "give the individual more freedom...from meaningless musts and silly shoulds." Even "sensible laws and rules" do "not apply under every set of circumstances." We should be free from "constant adherence to the shoulds," cultivating "flexibility and repeated personal assessments of how well the rule works at a particular present moment" (Wayne Dyer, Your Erroneous Zones, pp. 185-186). To "resist enculturation," one had to "become a shrugger," Dyer's term for one who walks away from useless confrontations. Others would" still choose to obey," and one would "have to learn to allow them their choice," with "no anger" at them, "only your own convictions." Dyer told a story of a Navy friend stationed aboard an aircraft carrier anchored in San Francisco when President Eisenhower visited California on a political tour. His fellow-sailors were ordered to spell out the words "HI IKE" in human formation, so that the President could look down from his helicopter and see the message. Dyer's friend "decided the idea was insane, and decided not to do it, because it conflicted with everything he stood for." But "rather than stage a revolt," he "simply slipped away for the afternoon, and allowed everyone else to participate in this demeaning ritual." He "passed up his one chance to dot the ^Ñi' in ^ÑHi.' However, he did this with "no put-down of those who chose otherwise, no useless fighting, simply shrugging and letting others go their own way" (Dyer, Your Erroneous Zones, p. 186). "Resisting enculturation" thus meant "making decisions for yourself and carrying them out as efficiently and quietly as possible," with "no bandwagons or hostile demonstrations where they will do no good." The "foolish rules, traditions and policies" would "never go away," but "you don't have to be a part of them," only "just shrug as others go through their sheep motions." If they "want to behave that way, fine for them but that's not for you." To "make a big fuss" was "almost always the surest way to incur wrath and create more obstacles for yourself." One could find "scores of everyday occurrences where it is easier to circumvent the rules quietly than to start a protest movement." (Dyer, Your Erroneous Zones, pp. 186-187). Wayne Dyer's "shrugger" ethic of quietly following one's own beliefs and interests without "useless fighting," of "shrugging and letting others go their own way" without making a "big fuss," like Russell's recommendation of sympathetic surroundings, might be seen by some observers as a good-naturedly cynical depiction of modern "little church around the corner" religious pluralism. Rather than wasting time and energy in "useless fighting" or a "big fuss," in what Russell called "a great dissipation of energy in the unnecessary task of maintaining mental independence against hostile surroundings," many of us simply leave an uncongenial church for one "around the corner" more suited to our own temperament, cultural style, or mental outlook. All this, of course, may seem both to some cynical atheists and to some zealous religious traditionalists like basic religious indifferentism or even polite crypto-agnosticism masquerading as "civilized," "reasonable" religion. I recently, for instance, read one such indictment of modern "mainstream" religion by a conservative British Anglican journalist quoted on the Anglican list. On Tuesday morning, January 1, 2002, an Anglican St.Sams list-member posted excerpts from an opinion piece by a Matthew Parris from the UK Times quoted in the previous Saturday's AnglicansOnline that he found thought provoking. Parris was described as arguing that "the events of the year, in particular the fanaticisms represented in the Middle East and Bin Laden, are somehow a clash of values between reasoning, thinking sorts and the fundamentalist fanatics." Parris felt that "modern" mainstream religion may just be agnosticism masquerading as observance, and that "reasonableness in religion comes from a lack of total commitment-- whether you are Jewish, Muslim, or Christian." The Anglican St.Sams list-member quoted Parris' concluding paragraph:

Stronger commitments from some, then, and stronger antipathy from others. Could things be coming to a head? Could we be seeing a polarisation of public attitudes to faith? For more than a century now the dominant attitude in the Western world has been an apathy which I would describe as covert agnosticism masquerading as weak observance. Is Osama bin Laden flushing this agnosticism out? If so, we may see an increase both in the religious enthusiasm of the minority, and the avowed scepticism of the majority. When it comes to the relationship between modern man and religious faith, the century now beginning may prove make-up-your-mind time. I hope so. Matthew Parris' description of "reasonable" Western religionists as covert agnostics reminded me a lot, when I read it, of atheist H.L. Mencken's 1916 "stage direction" of a wedding in an upper-middle-class church, which I'd just recently re-read. It also reminded me of the agnostic Czech-English Cambridge University social philosopher Ernest Gellner's somewhat acidulous view of modern Western liberal religion, and of the English "Fortean" researcher Hilary Evans' placing of modern "New Age" cults and gurus in the context of declining religious orthodox belief. Back in 1916, Mencken published a gently satiric "stage direction" for a wedding in a church in a "well-to-do but not quite fashionable" upper-middle-class neighborhood of businessmen, professionals, and their wives in a moderately large American city. The church was "Protestant in faith and probably Episcopalian." The "estimable wives" of its congregation's "well-to-do but not fashionable" businessmen, lawyers, and doctors were "pious in habit but somewhat nebulous in faith." This meant that "they regard any person who specifically refuses to go to church as a heathen, but they themselves are by no means regular in attendance, and not one in ten could tell you whether transubstantiation is a Roman Catholic or a Dunkard doctrine"[H.L. Mencken,. "The Wedding: A Stage Direction," from H.L. Mencken, A Book of Burlesques (Alfred A. Knopf/J. Lane, 1916), reprinted in E.B. White and Katharine S. White, eds., A Subtreasury of American Humor(New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1941), pp. 365-373, on p. 366] I've been reminded of Mencken's observations on "somewhat nebulous" faith by remarks on doctrinally vague modern religion both by the Cambridge University philosopher and social anthropologist Ernest Gellner and by the English "Fortean" researcher Hilary Evans. Both Evans and Gellner saw much contemporary Western religious observance as an expression far more of social conformity, cultural loyalty, and sentimental attachment to tradition than of deep theological conviction or clear theologicaol understanding. Gellner described religious fundamentalism as a repudiation of what he saw as the "doctrinal vacuity" of modern liberal theology in Postmodernism, Reason, and Religion (1992). Evans placed modern "New Age" UFO cults and gurus in the context of declining orthodox Judaeo-Christian religious faith in a 2000/2001 ANOMALIST article on "Do-It-Yourself Deities and Mail-Order Messiahs." Since the 17th century, Evans noted, the "unquestioning view" in the universality of religion as a "basic fact of human existence" that "distinguishes man from the beasts" has been "progressively weakened." It was "socially discreditable" until "quite recent times" to "proclaim disbelief," which it "still indeed is in many communities." However, a "substantial proportion" of people nowadays "affirm a total rejection of any orthodox belief." Moreover, "of those who continue to label themselves ^ÑChristians' or whatever" (e.g., Jews, Muslims, Hindus, or Buddhists depending on one's cultural background), it is "clear" that "many are no more than nominal believers who for social or psychological, rather than spiritual, reasons are unwilling to make a final rejection" (Hilary Evans, "Do-It- Yourself Deities and Mail-Order Messiahs," The Anomalist, No. 9, Winter 2000/2001, pp. 14-39, on p.17). That is, such nominal believers are afraid of the social stigma of being labeled "heathens," "unbelievers," or "atheists," the annoyance of being pestered by well-meaning relatives, friends, clergy, or evangelists trying to "save" them or "bring them back in the fold," or the bleak psychological chill of completely, formally cutting themselves off from cherished customs, ceremonies, and traditions. Many Catholics, Protestants, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, or Buddhists who have abandoned the theology and the sexual, dietary, alcoholic, or Sabbatarian restrictions still cherish warm, nostalgic childhood and adolescent memories of religious holidays, religion-related family celebrations, candles, hymns, organ music, stained glass, incense, "smells and bells," Christmas trees or Chanukah menorahs and dreidls, and familiar well-loved Bible, Torah, Qur'ân, or Book of Common Prayer verses, passages, and stories. They feel very reluctant to abandon these along with the dogma or mythology and the prohibitions on birth control, abortion, divorce, pork, beef, liquor, tobacco, Saturday work, Sunday amusements, homosexuality, or sexual intercourse with a menstruating woman..For all these reasons--nostalgia, fear of social stigma as "unbelievers," and dislike of meddlesome do-gooders trying to "save" them--they find it socially and psychologically useful and comfortable to maintain a connection with their ancestral religious communities, and to continue attending or even officiating at ceremonies and rituals, while maintaining a discreet, polite ambiguity about their exact actual beliefs. They may privately re-interpret ancient theological, credal, or ritual formulae as metaphoric expressions in quaintly archaic poetic or mythic language of some form of Deism, Spinozism, Kantianism, Neo-Hegelian Absolute Idealism, Emersonian Transcendentalism, Ethical Culture, Heideggerian Existentialism, or New Ageism--maybe just a vague, optimistic belief in a Life-Force or Oversoul slowly but surely working for the eventual triumph of truth, beauty, goodness, and justice. Like Mencken's 1916 "estimable wives," they do not want to be "heathens" who specifically refuse to go to church, synagogue, or mosque, but also are quite happy and even eager to be "somewhat nebulous in faith" with little interest in pedantic hair-splitting doctrinal niceties. Of "those who abandon traditional religions," Hilary Evans continued, "some reject religion altogether, becoming agnostics or atheists." Others, however, "turn to alternative faiths"--whether to other major traditional religions, or to modern "New Age," Spiritualist, Theosophist, and occult beliefs. "Publicized cases occur of prominent converts from Protestant to Catholic Christianity, from Christianity to Judaism or Islam, and so forth," Evans noted, but he felt that "it is their rarity that makes them notable" (Evans, "Do-It- Yourself Deities and Mail-Order Messiahs," p. 17). Evans then devoted the rest of his article to people who turn from Christianity or Judaism not to Islâm or Buddhism but to "New Age" beliefs and especially to UFO cults proclaiming the world's salvation by benevolent saucer-borne "Space Brothers." Both Mencken and Evans remind me of some observations about modern religion by Ernest Gellner in Postmodernism, Reason and Religion (London and New York:Routledge, 1992). Like Mencken and Evans, Gellner took a somewhat bemused, slightly ironic view of the "doctrinal vacuity" of modern bourgeois nominal believers nebulous in faith and unwilling to make a final rejection for social or psychological rather than spiritual reasons. Gellner felt that religious fundamentalism--by which he largely meant Muslim fundamentalism in most of his book--was "best understood" as a rejection of the "widespread modern idea" that "religion, though endowed with some kind of specified validity of its own, really doesn't mean what it actually says, and least of all what ordinary people had in the past naturally taken it to mean." What religion "really means," according to the "modernism" rejected by fundamentalists, was something "radically different from what its unsophisticated adherents had previously taken it to mean," and "far removed from the natural interpretation of the claims of the faith in question." Fundamentalism repudiated the "tolerant modernist claim" that the "faith in question" meant "something much milder, far less exclusive, altogether less demanding and much more accommodating; above all something quite compatible with all other faiths, even, or especially, with the lack of faith." Such modernism, Gellner felt, "extracts all demand, challenge and defiance from the doctrine and its revelation"(Ernest Gellner, Postmodernism, Reason and Religion ,1992, pp. 2-3) Faith, Gellner argued, is often seen nowadays "as the celebration of community." Belief in the "supernatural" is "de-coded as expression of loyalty to a social order and its values." The "doctrine de-coded along these lines" was "no longer haunted by doubt," as "there isn't really any doctrine, only a membership, which for some reason employs doctrinal formulation as its token"(Postmodernism, Reason, and Religion, p. 3). Elsewhere, Gellner described this view of religion as simply the conceptual, literary, and ritual expression of a culture or society celebrating its values, continuity, and solidarity as an "auto-functionalist" form of religious "faith" (Nations and Nationalism, 1983, p. 56; Plough, Sword, and Book, 1988, 1990, pp. 207-208). The "cosmogony of a given faith," in such "softened modernist re-interpretation," was "in effect treated not as literal truth," but rather "merely as some kind of parable, conveying ^Ñsymbolic' truths, something not to be taken at face value, and hence no longer liable to be in any kind of conflict with scientific pronouncements about what would, on the surface, seem to be the same topic." For example, "modernist" believers are "untroubled by the incompatibility between the Book of Genesis and either Darwinism or modern astro- physics." They "assume that the pronouncements, though seemingly about the same events- -the creation of the world and the origins of man--are really on quite different levels," or even "in altogether different languages, within distinct or separate kinds of ^Ñdiscourse.'" Generally, Gellner found, the traditional doctrines and moral demands of the religion are "turned into something which, properly interpreted, is in astonishingly little conflict with the secular wisdom of the age, or indeed with anything." This way, Gellner felt, "lies peace--and doctrinal vacuity" (Postmodernism, Reason, and Religion, pp. 3-4). Pax vobiscum, T. Peter Garden City South, L.I., N.Y. Special thanks to http://newark.rutgers.edu BibliographyMac Adam, George. The Little Church Around the Corner. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1925.Ray, J. H. Randolph. My Little Church Around the Corner. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1957. Ross, Ishbel. Through the Lich-Gate: A Biography of The Little Church Around the Corner. New York: William Farquhar Payson, 1931. Stuart, Suzette G. Illustrated Guidebook with Historical Sketch of The Little Church Around the Corner. New York: The Church of the Transfiguration, 1963.

|

|

|

links |

http://www.littlechurch.org/ |