|

New York Architecture Images-Gramercy Park 69th Regiment Armory |

|

|

architect |

|

|

location |

68 Lexington Ave. at 26th Street. |

|

date |

1904 |

|

style |

|

|

construction |

|

|

type |

Defense - arms storage |

|

|

|

|

images |

|

|

|

|

|

This formidable brick mass represents a type

of building that served in the dual capacity of military facility and

social clubhouse for units of the National Guard, particularly the

"Fighting 69th," the renowned local unit of the New York National Guard.

With roots going back to the American Revolution, this regiment served

with distinction during the Civil War, WWI and WWII. It is also

nationally significant as the site of the 1913 International Exhibition

of Modern Art, the first major exhibition of contemporary art in

America, that revolutionized the nation's artistic tastes and

perceptions. Some 1,300 works of art were displayed, and here for the

first time many Americans saw the works of Cezanne, Van Gogh, Matisse

and Picasso. A portion of this military facility is used as a homeless shelter. Loss of historic fabric, damage and vandalism have occurred. |

|

|

"In 1851, a group of immigrants formed a

militia Regiment to protect their new homes and their families. And they did...First on their own soil -- Then in France -- Then in the Pacific. And now -- at their nation's darkest hour -- they defend their homes and families again. On their own soil -- in their own city -- in New York. The home, for 150 years, of the fighting 69th. Gentle When Stroked, Fierce When Provoked." The Oak Falls After more than fifty years of service

under two flags, Sgt. John F. Mullins of the 165th (old 69th) Infantry

N.Y.N.G. has passed from the ken of men. "The elements were

so mixed in him June 1928

The 69th Mourns Its Lost Sergeant Here is a general view of the 69th Regiment

escorting body of Daily Mirror May 16, 1928 Sergeant John F. Mullins Buried With Military Pomp Procession of 3,000 Honors 165th Regiment Veteran Sergeant John F. Mullins, a soldier for fifty-four of his sixty-five years, was buried with full military honors yesterday in Calvary Cemetery by the 165th Regiment. Funeral services were held at St. Stephen's Church, on Twenty-eighth Street, between Lexington and Third Avenues, with Father Francis P. Duffy, regimental chaplain, presiding. Mass was sung by the Police Glee Club. Sergeant Mullins, who died last Friday at the 165th Regiment Armory, was with that organization for the last forty years, enlisting when the Regiment was known as the "Fighting 69th." Prior to that enlistment he had served fourteen years with the British Army in India and Arabia. Sergeant Mullins, who was Drum Major of the 165th, was an outstanding rifleman and one of the best buglers in the army. The procession was composed of the entire 165th Regiment and the regimental band, veterans of the Rainbow Division, veterans of the 69th Regiment, Spanish War veterans, representatives from every armory in the state of New York, a caisson and escort from the 104th Field Artillery, representatives of Governor Smith's staff and representatives of the Armory Board. There were about 3,000 in the procession. Three sons, Captain Fergus P. Mullins, 165th Regiment; John J. Mullins, a sergeant in the same regiment; Lawrence Mullins, a policeman; and five daughters, Mrs. Helen Collins, Mrs. Thomas Weppler, Mrs. John Clifford, Mrs. John Winters and Miss Margaret Mullins, survive. 69th Regiment Mourns Death of Its Fourth Soldier

in Iraq A yellow ribbon has been tied to the iron gates of the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue at 26th Street for the last nine months, ever since the Fighting 69th of the New York National Guard shipped out to Iraq from the huge brick structure. In December, the regimental and American flags that hang outside were dropped to half-staff to commemorate three soldiers from the unit who died this autumn in Iraq. Then, yesterday, the black and blue memorial bunting came out again. A veteran of the unit, walking somewhat shakily, solemnly draped two pieces across the gates to mark the death of the fourth soldier from the unit to have died so far in the fighting in Iraq. "I'm a civilian now, but I wanted to help," said Victor Olney, 62, a lean, clear-eyed former sergeant who served with the Fighting 69th from 1965 to 1971. "I wanted people from the neighborhood to know that local soldiers were serving overseas." The most recent member of the 69th Infantry to die was identified by his mother, Debbie VonRonn, as Pfc. Kenneth VonRonn, 20, of Pine Bush, N.Y. "He was a good kid, and he died doing what he wanted to do," she said. "He wanted to serve his country, and he went with honors." The Fighting 69th, whose men and women have literally traveled from ground zero to the Sunni heartland of Iraq in the last four years, has had a difficult few months. On Dec. 3, Staff Sgt. Henry Irizarry, 38, of the Bronx, died in Taji, Iraq, when a bomb exploded near his Humvee. In November, Christian Engeldrum, 39, a sergeant and a New York City firefighter, was killed when his Humvee struck a roadside bomb near Baghdad. Another member of the unit, Pfc. Wilfredo F. Urbina, 29, a volunteer firefighter from Long Island, also died in the attack. Private VonRonn was killed on Thursday when his Bradley armored personnel carrier was struck by a bomb about 20 miles northwest of Baghdad. Six other soldiers from a different outfit died in the same attack. Details of the attack were sketchy. The 69th is serving in Iraq with a unit from the Louisiana National Guard, the 256th Mechanized Infantry Brigade, said Lt. Col. Paul Fanning, a spokesman for the New York National Guard. He said more than 600 soldiers from the 69th Infantry were sent to Fort Hood in Texas in May to train with the Louisianans before being shipped off to Iraq this fall. All told, 11 members of the New York National Guard have died in the fighting in Iraq, Colonel Fanning said. A company from the Guard's Second Battalion, 108th Infantry came home from the war on Sunday. The 69th, formed in 1851 by Irish immigrants, is one of the most storied combat units in American military history. It fought in the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I and World War II. Its regimental cocktail is one part Irish whiskey to three parts Champagne, and over the years it has had at least two writers in its ranks - Joyce Kilmer, who wrote the poem "Trees," and Rupert Hughes, a playwright, novelist and screenwriter who was the uncle of Howard Hughes. Kilmer's poem "When the Sixty-Ninth Comes Back" was set to music after World War I and was played by the regimental band when the unit marched triumphantly up Fifth Avenue on its return from Europe. "With the Potsdam Palace on a truck/and the Kaiser in a sack," he wrote, "New York will be seen one Irish green/When the Sixty-Ninth comes back." With more than 600 soldiers in the unit still at war, veterans like Mr. Olney can only hope that their comrades will return soon. "All the members of the 69th are a family," he said after hanging up the final piece of bunting. "Everybody does their little bit to help."

|

|

|

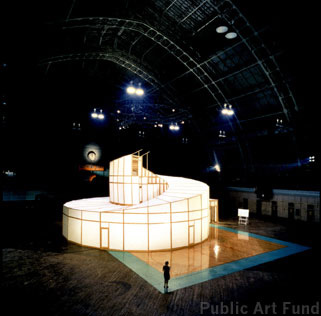

Welcome to the 1913 Armory Show

|

|

|

Armories, Military Installations Close

Doors to Antiques-Related Events by David Hewett The events of September 11 wreaked havoc on New York City and brought changes to the daily lives of Americans everywhere. They also affected the antiques show circuit. Armories across the country reverted to their original military missions, which some had forgotten, or never knew, existed. New York City writer Fran Lebowitz recounted her experience with that subject on a National Public Radio newscast three days after that Tuesday's events. She left her apartment in the morning and observed army tanks rolling down the deserted canyons between skyscrapers. A man stopped her in amazement. "Where did the tanks come from?" he asked. "The Seventh Regiment Armory," she answered. "They have tanks there?" he said. "I thought they only held antiques shows there." Wendy's New York Armory Antiques Show, scheduled to be held September 19-23 at the 7th Regiment Armory (Park Avenue at 67th Street) in New York City, was immediately canceled. Forbes and Turner's Fall Hartford Antiques Show of September 29 and 30 was moved from the Connecticut State Armory to the Expo Center in Hartford. Anna and Brian Haughton canceled their International Art & Design Fair and benefit for the Museum of Modern Art, which had been scheduled for September 28-October 2 at the 7th Regiment Armory. They had made tentative plans for their International Fine Art and Antique Dealers Show, scheduled for October 19-25 at the armory, to move to the tenth floor of Sotheby's, but they met immediate resistance from exhibitors. The New York Times reported in a September 27 story by Carol Vogel that most of the 72 exhibitors "were so outraged that they pulled out of the show, saying that doing a fair at the York Avenue auction house would be `sleeping with the enemy.'" Vogel said the exhibitors were also worried that the move from a ground floor space to the tenth floor "would significantly reduce traffic at the show." Matthew Weigman of Sotheby's explained how they got involved. "We were called by the Haughtons' staff, who essentially said `Help!' Bill Ruprecht said yes, and we began planning to move all the exhibitions off that floor to somewhere else." "It isn't like October is a slow month. My God, it's high season, one of our busiest times, and we had planned to use that space for several previews, but we wanted to help the antiques business out. We weren't even charging them anything. We were willing to give them the use of that floor for free." Debra Davis at the New York City office of the Haughtons said that the New York Times story was not entirely accurate. "A few of the dealers did resist the move to Sotheby's for the reasons given in the story, but it wasn't the numbers mentioned [in the Times story]. The greater problem for most dealers had to do with logistics. The armory has thirty thousand square feet. Sotheby's space has considerably less than that, which meant drastic changes in exhibition areas." Debra Davis confirmed on October 3 that the International Fine Art and Antique Dealers Show had been canceled. At least one New York City auction firm was physically unreachable after the attacks. R.M. Smythe and Company, located at 26 Broadway, was within the no-go zone around the World Trade Center. Smythe suffered no physical damage to material on hand and lost no members of the firm, according to a company spokesman. Smythe, which sells antique stocks and bonds, banknotes, coins, autographs, and photographs, had material in its vaults that was scheduled to be sold later in September. Smythe posted the following advisory on its Web site: "Circumstances beyond our control made it necessary to postpone the September 14th-15th Strasburg Currency and Stock and Bond Auction #213. It will now take place on Friday and Saturday, November 16th and 17th, at the Crowne Plaza St. Louis Airport Hotel...St. Louis, Missouri." Philadelphia's Fall Antiques Show, scheduled for October 19-21 at the Naval Business Center in Philadelphia, was canceled. Frank Gaglio said that Barn Star Productions received word from the Delaware River Port Authority on September 24 that navy activities would preclude the use of the site for an antiques show. "It's a major financial hit for us, but we will refund all the exhibitors' deposits in full," Gaglio said. Stella Show Mgmt. Co. quickly adapted to the news that the 69th Regiment Armory on 26th and Lexington in New York City was off limits for its October 5-7 Gramercy Park Modern Show. Stella moved the show to Madison Square Garden. "Talk about doing things in a New York minute," Irene Stella said. "We are feverishly working to make this the best modern show yet." The Antiques and Textiles Show Stella had planned for the 69th Regiment Armory for October 19-21 has been postponed. A makeup date had not been set at press time. Stella has moved the Triple Pier Antiques Show, originally scheduled for two consecutive weekends on November 10-11 and 17-18 at Piers 88, 90, and 92, to the Jacob Javits Center at 11th Avenue and 36th Street. It will be held on one weekend only, on November 17 and 18, according to Nancy Mancini at Stella's office. Other promoters were still clinging to the hope that their late October shows at the 69th Regiment Armory would go forth as planned, even after the New York National Guard announced in late September that all nonmilitary use of armories across New York state had been banned for an indeterminate period. At press time, Sanford L. Smith & Associates still has the Trinity Eastside Antiquarian Book Fair planned for October 26-28 at the 69th Regiment Armory, or barring that, at another location within the city. On October 3, Susan Dixon of Sanford L. Smith & Associates said, "We still don't have any definitive word about whether that show can go on as planned. We're hoping that it will, of course, but there's a possibility it won't." There are also further problems down the road for Smith. "The book fair is just one of a number of shows scheduled in New York throughout the rest of the season," Dixon said. Sanford L. Smith & Associates has three shows scheduled for November. "We've considered the Sotheby's space, but there are problems," Susan Dixon said. "Some of our exhibitors agree with the comments made by the Haughtons' exhibitors about `sleeping with the enemy.'" She also noted that the space restrictions would also be a major factor in using Sotheby's. At this time, the possibility exists that any show scheduled in a government facility may be canceled. Even in rural New England, some armories are off limits, and parking near federal buildings is restricted. The 32nd annual Concord (Massachusetts) Antiques Show and Sale, sponsored by the Trinitarian Congregational Church, scheduled for October 26-27 at the armory in Concord, has been canceled. In Maine, it's a different story. The 54th Augusta Armory Antiques Show, scheduled for November 10-11 at the armory on Western Avenue in Augusta, is, as of press time, still expected to run as normal. Promoter James Montell, however, must now pay for two members of the National Guard to be present at all times during the show. The financial losses from physical damage alone will be huge. AXA Nordstern Art Insurance, the world's largest art insurer, estimated art losses from the World Trade Center attacks at more than $100 million. The amount of art destroyed in surrounding buildings is unknown. The potential economic losses caused by continued cancellations of New York City shows are equally large. At a press conference held on October 5, 40 show management companies, equipment suppliers, union representatives, and other groups met at Madison Square Garden and aired the problems and implications of the shutdown. Among that group were representatives from Sanford L. Smith & Associates, the Haughtons, Stella Show Mgmt. Co., the Armory Art Show, and the Art Dealers Association of America. In a written statement, Irene Stella said, "Most fall events here have been lost. The next big season is January. Five or six antiques events are held in one week alone that month, all surrounding the venerable Winter Antiques Show." Stella continued, "Trade and consumer shows are booked years in advance. Can we count on assistance in restoring exhibit space in New York or must we move to other cities?" Sanford Smith's written statement put a price on the closings. "There are sixty-eight Art, Antique, Design, Book and Craft Shows in New York City between September and June. During this ten month period, the number of exhibitors in these sixty-eight shows exceeds 5,000 from the United States and twelve foreign countries." According to Smith, "Sales Tax revenue to New York City and New York State is estimated at $5-7 million a year. Overall, the shows produce in excess of $100 million a year for the City and State economy. Every dollar that is spent on the shows multiplies to the equivalent of three or four dollars within New York City's economy." Lost works of art and revenues from show closings become minor losses when balanced against the enormous loss of life suffered on September 11. As far as we can tell, the antiques industry lost only one active member, dealer Georgine Corrigan, 56, of Hawaii. Corrigan had just completed a buying trip on the East Coast and was on United Airlines flight 93 when it crashed into a field in Pennsylvania around 10 a.m. on that Tuesday. Stella Show Mgmt. noted that part-time worker Shawn Powell, a New York City fireman on Engine 207, was missing and presumed dead. Stella donated 100% of the profits from the Waterloo Antiques Fair in Stanhope, New Jersey, on September 22-23 to the Twin Towers Fund, which aids the families of lost police and fire workers. © 2001 by Maine Antique Digest |

|

|

The Armory Show Thesis by Linda Larson In the early 1900s, America was a nation in transition, ripe for evolutions in politics, social systems, literature, and certainly art. It was an era of world war, prohibition, prosperity, the Great Depression, and a time of decadence giving birth to a daring and lively generation that challenged the lifestyle and ideals of the past. The aspiration and rebellion of American artists was not so much concerned with radical politics or the class struggle, but expressed an intense desire to declare the awakened new sense of life in themselves and their society. They wished to substitute a more tolerant spirit for the moral indignation, dismissal, and restraints imposed by their "old society," The Academy (Joachimides and Rosenthal 49). The shifting artistic values occurring in America pushed aside the ordered tradition of the Academy and assailed it with a new means of expression--realism. American Realism introduced new themes that challenged the gentility of the past with images considered unacceptable and vulgar. It shifted and revolutionized society with a style and subject matter that reflected the nation's newfound interest in ordinary people, especially those of the working class. However, the changes in artistic expression were just beginning. Within a few years, the artistic traditions of several centuries were shaken to the very foundation and the new "modern" art of the twentieth century burst forth, forging the way for a new standard and a new definition of art. In the course of the nineteenth century, Classicism, Romanticism, Realism, and Impressionism followed each other rapidly and weakened the idea of an ideal model or style. The Academy did recognize that art creates many different forms, so tastes were not necessarily disputed up to this time providing that artists observed certain minimal rules. Yet, what the Academy considered a universal language of colors and forms was unintelligible when conventions changed. An artistic line emerged between the Academy and the modern artists with stark colors of black and white and the style right or wrong. The new art, considered a negation of the basic values of academic art, challenged the whole education method. For centuries, the artist’s training had been in the study of the nude figure, in drawing and painting from careful observation of the model, and in the copying of works of the old masters. In the minds of the Academy, what good was long practice in representation when the aim of the painter or sculptor was to create works in which the human figure scarcely existed or was deformed at liberty (Schapiro 164)? Understandably, these opponents of modern art felt that they defended a threatened heritage, and in the name of all past and sacred values, they opposed a new possibility of freedom in art. In the face of such opposition, American artists, confident of the necessity that art relate to contemporary life, appealed to freedom and modernity. By 1911, in response to the conventional restrictions authorized by the National Academy of Design, a frustrated group of inspired modern artists formed the American Association of Painters and Sculptors (AAPS). They abandoned any obligation to realistic depiction, and as their realist predecessors had done, they cast aside allegiance to an academic ideal in favor of a newfound freedom. In their “modern” world, vision was not restricted to ideal forms, noble subject-matter, harmony, decorum, and nature, but instead relied on an insightful, unfettered, soulful perception. These spirited outsiders did not belong to any particular school of art, and several had shown at the National Academy itself, yet whether out of defiance or necessity, they believed that the time had come to acquaint the general public with the vital new movements of modern art. Their first exhibition was to be a great show of modern American painting and sculpture at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York but expanded into the international show known as the “Armory Show.” Opening on February 17, 1913, the Armory Show marked the end of an era, and the critics of the time described the exhibition as a crisis in American art. However, the Armory Show was not a crisis for the American modernists, but a triumphal entryway beckoning future artistic liberty. If the exhibition had been merely of bizarre, insincere work, or incompetent painting (as the critics described), the impact would have been slight and one quickly forgotten. Thankfully, these bold “lunatics” did not fail their vision since the process and fate of American art was in their hands alone. The first group of American artists to advocate a new kind of art and to explore the everyday life of ordinary people in large cities came to be known as “The Eight,” or in reference to their concept, “The Ashcan School.” Led by Robert Henri (1865-1929), they shared a passionate conviction that painting must reflect the artist’s involvement with life as it is lived. Although their paintings represented an abrupt departure from contemporary academicism, eventually the new direction of The Eight would emerge more in content and viewpoint then in style. Robert Henri believed that American life and daily experience was a deserving subject matter for art. Henri’s avocation, once said John Sloan, a protégée of Henri’s, was “making pictures of life” (qtd. in Hunter and Jacobus, American 50). “Life” became the operative word in Henri’s vocabulary, the litany of his teaching. “It referred not so much to the artist’s recording of an object in the external world as to the inward sensation of ‘being alive,’ enhanced by the act and exercise of Painting” (Brown et al. 352). Henri pleaded for the viability of human emotions. “Because we are saturated with life, because we are human,” he remarked in the 1923 edition of The Art Spirit, “our strongest motive is Life, humanity; and the stronger the motive back of the line, the stronger, and more beautiful, the line will be…. It isn’t the subject that counts but what you feel about it” (qtd. in Hunter and Jacobus, American 50). In 1891, Henri had met a group of young artist-illustrators who had been working for Edward Davis, the art director of the Philadelphia Press. They were William Glackens, George Luks, Everett Shinn, and John Sloan. Henri imparted to these young men a new cosmopolitan spirit, urging them to travel abroad and to devote themselves to oil painting rather than to illustration. In 1904, he set up a school of his own in New York City’s Lincoln Arcade, in the Latin Quarter district on upper Broadway. Gathered there were all the rebels against the genteel tradition: the Philadelphia artists who had followed Henri to New York, and others, such as George Bellows and Glenn O. Coleman, who were to associate themselves with the New Realism (Arnason 420). Henri “redirected the [Philadelphia group’s] attention to subjects taken from contemporary city life--rooftops and backyards, Bohemian restaurants, ferryboats, and crowded streets” (Brown et al. 353). Following his example, the group members were innovative primarily in subject matter rather than in formal structure or style, changing in their attitude not toward painting but toward life. Compared to contemporary European artistic developments, their work was not revolutionary; however, the “vulgarity” of their subject matter was enough to provoke sharp criticism for a time, at least, until their offences paled beside the public outrage aroused by the introduction of avant-garde modernism at the Armory Show of 1913. Overnight, the Armory Show made realism seem conservative and dated. Still, The Eight were the first Americans in the century to revive an insurgent mood, to depict urban ugliness, and to venture into the modern mainstream by breaking the hold of the academic past. The Realist group’s new departures in mood, subject matter, and social attitude, if not in style and technique, soon aroused the open hostility of the official art world. The challenge of Henri, Luks, Sloan, Glackens, and Shinn to contemporary authority met with increasing rejections of their work by the National Academy and the Society of American Artists. Suppression by these institutions, as well as by the small number of private art galleries then showing works in America denied the artists public exposure. When, in 1907, the jury for the National Academy voted to exclude entries by several members of his group; Henri withdrew from the exhibition in protest. With Glackens and Sloan, Henri formulated plans for a counter exhibition that would be the first large independent's show of the new century. The Show took place at the Macbeth Gallery in New York in 1908. Henri, Sloan, Luks, Glackens, and Shinn, the original Philadelphia rebels were joined by Maurice Prendergast, Ernest Lawson, and Arthur B. Davies. The group immediately became known in the newspapers as the "Eight Independent Painters," or simply "The Eight." Their Realism won them such derisive titles in the press as "the Revolutionary Black Gang," "The Apostles of Ugliness," and the best known, "Ashcan School" (Brown et al. 362). The term "Ashcan School" was not actually coined until 1934, by which time the progeny of the first generation of painters had broadened the scope of New York City realist painting. Like their predecessors, many of the younger artists had socialist, if not Marxist, sympathies that were reflected in their art. The group included George Bellows, Edward Hopper, and Reginald Marsh, to name three of the most important. There were, in fact, dozens of painters who were making urban realism the foundation of their art (Craven 432). In their first and, as it turned out, only exhibition as an organized group, The Eight experienced financial success despite the bad press. For the most part, they were derided by journalists for the usual reasons that commonly brought Realism under attack: its treatment of common everyday themes, or in the words of one reviewer, its "unhealthy nay even coarse and vulgar point of view" (qtd. in Brown et al. 362). The Realists were also chastised for their "poor drawing" and "weak technique" (Brown 362). Another objection was that the art exhibited was "revolutionary." In spite of, or possibl because of, the sniping journalists, the public came in droves. The new mutinous spirit could no longer be either contained or denied. However, this 1908 grouping was never repeated, and organized dissent died with the decay of the Society of American Artists. Nevertheless, "The Eight" maintained their enthusiasm and began plans for bringing new currents of art to the American Public. "Eventually the 'men of rebellion' expect to have a gallery of their own," The New York Herald reported in 1907, "where they...can show two or three hundred works of art. It is likely, too, that they may ask several English artists to send over their paintings from London to be exhibited with the American group. The whole collection may be shown in turn in several large cities in the United States" (qtd. in Hunter and Jacobus, American 64). This statement anticipated the huge "Exhibition of Independent Artists" organized in 1910 by the original members of the Eight and such followers as Rockwell Kent, George Bellows, and Glenn Coleman. Henri reviewed this exhibition for The Craftsman in 1910, presenting a lengthily, personal statement of his philosophy of art, and included a spirited defense of the artists' freedom to think and to represent those thoughts through their works (Arnason 420). With its courageous precedent of eliminating the academic position of privilege and overcoming restrictive qualifications for entry, the independents' exhibition of 1910 foreshadowed New York's great adventure and discovery of international modern art of a radically different sort at the 69th Regiment Armory in 1913. Overnight, the Armory Show made realism seem conservative and dated. Still, The Eight were the first Americans in the century to revive an insurgent mood, to depict urban ugliness, and to venture into the modern mainstream by breaking hold of the academic past. The year 1908 saw the Realism of The Eight established, but it also inaugurated Alfred Stieglitz’s (1864-1946) exhibitions of the radical European moderns. Stieglitz represented a new type of Jewish-German descent whose parents had immigrated at the time of the Civil War. By 1900, the massive waves of immigration to America began to affect the art scene, giving it a more international character and making the port of New York a more cosmopolitan cultural center. Stieglitz “saw himself and his artists as workers in the cause of creative freedom, and his “291” gallery took on a symbolic character” (Brown et al. 378). By introducing innovative art and changing the nature of its patronage, Alfred Stieglitz did more than anyone in America to transform this state of affairs (Arnason 421). Almost single-handedly, he turned the gallery of contemporary art into a gallery of modern art. A photographer and gallery director, Stieglitz launched his first vanguard project, the magazine Camera Work, in 1903. Naturalism served Stieglitz, as it had the Ashcan artists, as a way of breaking clear of the beaux-arts style (Altschiler 72). Within a few years, after making contact with Leo and Gertrude Stein in Paris and taking advice from the photographer Edward Steichen, Stieglitz was fired with a passion that gave a new direction to the little gallery he had opened in 1905 on 291 Fifth Avenue. Stieglitz introduced European moderns by exhibiting their work in his gallery and by doing so opened a fresh world of art to many Americans. Eventually, Stieglitz turned away from the European vanguard to promote the unrecognized American avant-garde. He began to add “American” to everything he did. “He billed his wife’s 1923 show as ‘Georgia O’Keefe American’ and called the large exhibition that he curated two years later at the Anderson Galleries ‘Seven Americans’” (Altschuler 69.“ His Intimate Gallery, a successor to “291,“ was inaugurated in 1925 as an “American Room” and featured the work of O’Keefe, Dove, Hartley, Stieglitz himself, and other Americans (Joachimides and Rosenthal 157). Henri taught and inspired young artists to experiment and reach beyond learned convention to paint “life” as they saw it. Stieglitz promoted and encouraged these same artists by making their work available to the public. Following 1908, a number of exhibitions opened in New York helping to prepare the public for the newest art. In this continuous process, the Armory Show marks a point of acceleration, lifting people out of the narrowness of complacent provincial tastes and compelling them to judge American art by a world standard. Another influential figure in the New York City art world of the era was Arthur B. Davies (1862-1928). Although he exhibited in The Eight show of 1908, his work differed significantly from that of the realist members of the group. Critics frequently described Davies’s paintings as “innocent,” “childlike,” and “naïve” (qtd. in Craven 432). His work actually compared to the fantasy imagery of the Symbolist movement, especially in its dreamlike aspects. The Symbolists’ work emphasized subjective and emotional qualities. Paul Gauguin was one, and his friend Vincent van Gogh another. The American Symbolists developed independently of the Europeans and were represented by Albert Pinkham Ryder and Ralph Blakelock, among others. Davies work during the opening years of the new century is characterized by unicorns and maidens in a woodsy, dreamlike setting. His work typically dealt with similar themes of poetic visions far removed from the realities of urban life. When Robert Henri began to mobilize his forces in rebellion against the National academy, Davies joined the Association of American Painters and Sculptors and was instrumental in getting Macbeth’s gallery for the 1908 exhibition of The Eight. In the proceeding years, Davies also assisted Henri and Rockwell Kent when they organized the Independent Artists Exhibitions of 1910 and 1911 (Altschuler 62). Of the original members of the AAPS, Davies had the most knowledge of contemporary developments in European art. Davies regularly visited exhibitions at “291” and had purchased from Stieglitz works by Cezanne, Picasso, and Max Weber. Although his own paintings were romantic and symbolist in style, he had a solid reputation and was considered broad-minded by his colleagues. Davies was elected president of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors because of his strong will, definite opinions, great energy and organizational ability, but the mild-mannered Davies would soon be described as a “dragon evolved from a very gentle cocoon” (qtd. in Altschuler 62). Inspired by the immense International Exhibition of the Sonderbund in Cologne, Davies sent an exhibition catalogue and short note to his collaborator, Walt Kuhn, in Nova Scotia, saying, “I wish we could have a show like this” (qtd. in Altschuler 60). Kuhn made arrangements to see the exhibition and arrived just before the close. What he saw became the model for the most famous art exhibition of the century (Altschuler 60). The “we” Davies referred to was the Association of American Painters and Sculptors. Originally, the AAPS planned only to exhibit some foreign art along with its own work, but Davies’s goal was to show American artists and their public what Europeans were accomplishing. His aggressive inclusion of European modernism in the Armory Show changed the course of American art. Prior to his visit to Cologne, Walt Kuhn had seen virtually no advanced European art. What he saw there was amazing. The centerpiece of the Sonderbund was a retrospective of one hundred twenty-five paintings by van Gogh, flanked by more modest retrospectives of twenty-five Gauguins, mostly Tahitian pictures, and twenty-six Cézannes. Neoimpressionism was represented by seventeen works by Henri Cross and eighteen Signacs. The sixteen Picassos extended across the rose and blue periods into important Cubist works, and then were seven Braques. Other French entries included Bonnard, Vuillard, Matisse, Derain, Vlaminck, Marquet, Maillol, and Marie Laurencin. There was a retrospective of thirty-two works of Edvard Munch, and other Norwegian, Swiss, and Dutch painters, including Mondrian and van Dongen. The Germans were well represented, including the artists of Die Brucke, the Blaue Reiter, and the NKVM [New Artists’ Association of Munich]. (Altschuler 60) The aesthetic education that Kuhn received that day in Cologne soon was to be provided to Americans in New York, Chicago, and Boston. However, its nature and impact was very different. The original aim of the Association was to present a show that reflected the inspiration and new confidence of American artists in the importance of their work and of art in general. Nevertheless, overlaid by another, their first exhibition became an international show in which European paintings and sculptures far surpassed in interest and overshadowed the American work. The change in the intention of the show, the idea of the president, Arthur B. Davies, was inspired while traveling a road. Davies and Kuhn were impressed by the new European art that they had known only slightly and by the great national and international shows held in 1912 in London, Cologne, and Munich. Caught up in the tide of advancing art, they were carried beyond their original aims. The Armory Show elicited an extraordinary range of feelings from the public as well as the art world. Some people responded with great enthusiasm while others could hardly contain their bewilderment, disgust, and rage with the new curiosity. For months, the newspapers and magazines were filled with caricatures, lampoons, photographs, articles, and interviews about the radical European art. Art students burned a copy of a painting by Matisse in effigy, violent episodes occurred in numerous other schools, and in Chicago, the show was investigated by the Vice Commission after a complaint from outraged moralists. So disturbing was the exhibition to the society of artists that painters like Sloan and Luks, who the day before had been considered the rebels of American art, repudiated the vanguard and resigned. Because of strong feelings aroused within the Association, it broke up soon after, in 1914, and the Armory Show was its only Exhibition. For years afterward, the show was remembered as an historical event, a momentous example of artistic insurgence (Schapiro 136). The Armory Show kindled the first public discourse on modernism in the United States. Abraham A. Davidson’s summary of the Armory Show titled “The Armory Show and Early Modernism In America,” describes the show’s impact on the American public, private collectors, and future museum collections: The International Exhibition of Modern Art of 1913, popularly known as the Armory Show because it was held from 17 February to 15 March at the 69th Infantry Regiment Armory in New York, was far reaching in its impact. Between 62,102 and 75,620 people paid to see some 1,300 European and American works, beginning chronologically with a miniature by Goya and extending to the present. Thus, the show was an extravaganza. Although there were large gaps -- the futurists as a group themselves--the Show represented many of the major artists and most adventurous positions from the end of the nineteenth century up to 1913.Improvisation by Wassily Kandinsky; and four Marcel Duchamps, including Nude made by private collectors, which would later pass into the public domain and form the beginnings of prominent museum collections of modernists art. These collectors included Dr. Albert C. Barnes; Lillie P. Bliss, who bought works by Cézanne, Gauguin, Redon, Renoir, and Vuillard; John Quinn and Arthur J. Eddy, who acquired, respectively, thirty-one and twenty-three pieces; and Walter C. Arensberg. (39) Although the reaction of the public, critics, and collectors was overwhelming, it did not start out that way. At first the crowds did not come. Three weeks into the exhibition, attendance began to mount, and it grew in the last week to a peak of approximately 10,000 on the final day. On the last day, lines circled the block, traffic jammed the streets around the Armory, and the doors had to be closed from 4 p.m. on because of overcrowding. For by then, the opposition's press had marshaled its forces, providing many comic interpretations of Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase and describing Brancusi’s Mlle. Pogany as “a hard-boiled egg balanced on a cube of sugar.” Even the sympathetic New York American entitled its February 24 piece on the show, “Is She a Lady or an Egg?” (Altschuler 67) For The Artists who visited the show, the experience inevitable was traumatic in one way or another. According to Walt Kuhn, “Old friends argued and separated, never to speak again. Indignation meetings were going on in all the clubs. Academic painters came every day and left regularly, spitting fire and brimstone--but they came--everybody came” (qtd. in Altschuler 69). Newspaper cartoonists and journalists mocked the Show with a series of cartoons published in the Evening Sun titled, “Seeing New York with a Cubist.” Additionally, political cartoonists took up the Cubist theme as well...showing Woodrow Wilson proudly painting a falling faucet entitled Tariff Descending Downward. A slew of humorous verses were painted...[such as] The Cubies ABC, with each letter of the alphabet lampooning some part of the show; and there were such mocking events as an exhibition by the “Academy of Misapplied Arts” for the benefit of the Lighthouse for the Blind.” (Altschuler 73) Since the newspapers had contributed so much (even though indirectly) to the success of the Armory Show, the AAPS invited “our Friends and Enemies of the Press” to a “beefsteak dinner” on March 8. During the dinner, waitresses sang and danced, speeches were made, and comic telegrams were read. Many had been both excited and disturbed by the exhibition as “It was a good show, but don’t do it again” (qtd. in Altschuler 73). The irony of such a statement was that it did not have to be done again, for the Armory Show triggered the sort of interest in the new art that ordinarily would have taken years to develop. The show made enthusiasts of many who would influence art in years to come, such as the thirteen-year-old Betty Parsons, future dealer of Jackson Pollock and the Abstract Expressionists, and Walter Arensberg, who saw the exhibition on the last day and would move soon from Boston to New York to be at the center of the modernist development in America. The exhibition diminished in size as it traveled, with the American section in Chicago including only works by the members of the AAPS, and the Boston show contained foreign art alone. But in Chicago, during its three and a half weeks at the Art Institute, over 100,000 more people visited the exhibition than had done so in New York. In anticipation of the opening, the Chicago Record-Herald on March 20 tried to prepare its readers for what they would see: Cubist Art--The portrayal in one perfectly stationary picture of about 5,000 feet of motion pictures: a “woosy” attempt to express the fourth dimension. Futurist Art--Same as the former, only more so, with primeval instincts thrown in; Cubism carried to the extreme or fifth dimension. Post-Impressionism--The other two thrown together. How to Appreciate It--Eat three welsh rarebits, smoke two pipefuls of “hop” and sniff cocaine until every street car looks like a goldfish and the Masonic Temple resembles a tiny white mouse (qtd. in Altshuler 76) The remaining days of the AAPS were not happy ones despite the Armory Show’s great success. The attention that the European art drew had turned the tables on the artists of the Henri group. Before 1913, these American Realists had been considered avant-garde in their art, at least to a public unaware of “291,” but now found themselves viewed as passé. By bringing modern art to the attention of a greater public, inspiring collectors and patrons, creating a market in which galleries would survive, the Armory Show was of single importance for the new American art and laid the foundation for the development of American modernist abstraction replacing American realism The Armory Show contained about sixteen hundred pieces of sculpture, paintings, drawings, and prints; it included a large American selection that comprised three-quarters of the exhibition. Remarkably, the entire exhibition is said to have been hung in only two days, beginning on February 13. The process was facilitated by Davies preparing a watercolor sketch of every room. By the time of the press preview on Sunday February 16, the Armory had been decorated with pine tress, yellow cloth streamers forming a canopy from the ceiling, and garlands of greenery hanging from the partitions and along the walls. The poster for the Armory Show depicts the pine-tree flag of the American Revolution proclaiming liberation from the art of the past (Schapiro 135). Nude Descending a Staircase Bruce Altschuler describes the layout of the Armory Show in his book The Avant-Garde in Exhibition: The physical arrangement of the eighteen octagonal rooms of the exhibition centered on the Europeans, with a row of six rooms on each of the north and south walls mostly showing American works. Entry was through the room of American sculpture, commanded by George Grey Barnard’s marble Prodigal Son, from which one could walk straight ahead to the large room of French painting and sculpture. Off to the left was the show’s main attraction, the Cubist room--known as the Chamber of Horrors--with the lines waiting to see Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase (65) The catalogue of the Armory Show, which lists about 1,100 works by over 300 exhibitors, of whom more than 100 were Europeans, is incomplete. Many works added in the course of the exhibition were not catalogued, and groups of drawings and prints by the same artist were listed as single works. Some estimate that the show comprised altogether about 1,600 objects. Nonetheless, despite the actual number of exhibits, the Armory Show had direct impact on American art, and a few artists having been exposed directly or indirectly radically altered their styles, choosing to work more abstractly. For example, European modernism inspired many American artists to reconsider form experiment with pattern, and incorporate rhythm into their own creative process. The “slashing brush strokes” that once proved “daring” now proved not enough (Rose 62). Although many remained true to artistic realism, their realism transformed into more conceptual art. The revolution of modern art was fought first by certain artists in the trenches. Later, the war was won by converted and enlightened patrons of art. As an opening battle, the Armory Show forged a courageous new path. The established values in the art world were shaken; purchases of Impressionist, Post Impressionist, and twentieth-century European art increased astoundingly after 1913; and the market for the modern art expanded rapidly (Hunter and Jacobus, Modern 106). It is hard to understand today how difficult exhibition conditions were for modern artists in the early 1900s. One cannot help but wonder if Robert Henri was referring to the Armory Show when he said: Critical judgment of a picture is often given without a moment’s hesitation. I have seen a whole gallery of pictures condemned with a sweep of the eye. I remember hearing a prominent artist on entering a gallery declare “my eight year-old child could do better than this.” The subject of the charge was a collection of modern pictures with which the artist was not familiar. There were pictures by Matisse, ézanne and others. Works of highly intelligent men; great students along a different line. The works, whatever anyone might think of them, were the results of years of study. The “critical judgment” of them was accomplished in a sweep of the eye. (Henri 192) One measure of the significance of the Armory Show is reflected in the following comment: “The wider recognition accorded modernism, and its relative success after the Armory Show, are due in great part to the efforts of a few early patrons, collectors, critics, and dealers in whose activities Americans may take a justifiable pride” (Hunter and Jacobus Modern 104) The Armory Show did sell and promote new art, but more importantly it challenged and changed both the Academic and intellectual definition and attitude toward art and brought cultured America face to face with the question of what makes art Art. The Armory show was a moment allowing America to see beyond the usual. In the words of Robert Henri, Art is simply a result of expression during right feeling. It’s a result of a grip on the fundamentals of nature, the spirit of life, the constructive force, the secret of growth, a real understanding of the relative importance of things, order balance….There are moments in our lives, there are moments in a day, when we seem to see beyond the usual. If one could but recall his vision by some sort of sign. It was in this hope that the arts were invented.. Sign-posts on the way to what may be. Sign-posts toward greater knowledge. (Henri 226) Lexington Avenue from 25th Street to 26th Street, 68 Lexington Avenue, Manhattan Built in 1904 Home court of the Knicks professional basketball team from 1946 thru the 1950 Capacity: 5,000 Shows conducted during the 1920s & 1930s Still in existence |

|

|

links |

http://www.fighting69th.com/news.htm |