|

|

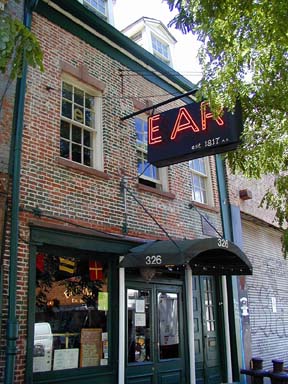

Ear Inn has colorful

history and uncertain future

By Albert Amateau

Keeping a 186-year-old wooden beach house standing and functioning as

living quarters, office and pub is no easy task. Especially one condemned as

unfit for use back in 1906.

But Rip Hayman, owner of the James Brown House at 326 Spring St. gets

along, with a little help from friends.

The house, built before 1817, is a designated landmark and the Ear Inn, a

pub on the ground floor, is a favorite neighborhood destination.

Recently, the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation joined

with Hayman and Andy Coe — author of “Ear Inn Virons,” a book (as its

punning title indicates) about the history of the property and

neighborhood — in a guided tour of the building.

The three-story house, originally the home of an African-American

Revolutionary War veteran who ran a tobacco shop on the ground floor,

has uneven floors, stairs that slant at an odd angle and a unique

ambiance.

“This is sand from the foundation of the building,” said Hayman, holding a

beer stein full of grayish sand. The house, now a block and a half from

the Hudson River, was right on the riverbank in the early decades of the

19th century. “There was a sand spit in the river at Canal St. at that

time,” said Hayman. “We have to pump out the tide from the basement

twice a day.”

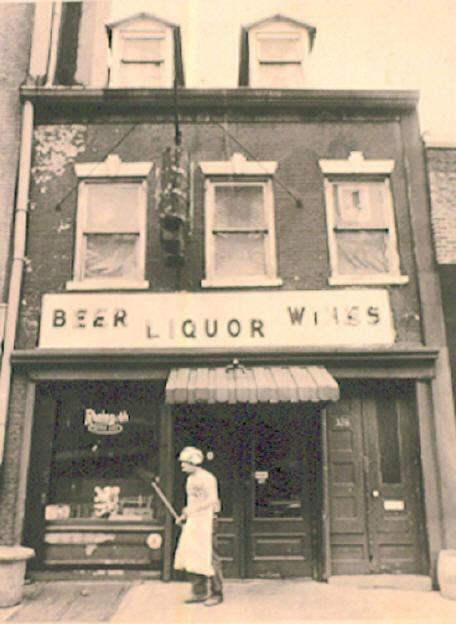

Hayman first rented a room in the house in 1973 when he was a Columbia

University student. He paid $100 a month rent to Harry Jacobs who ran

the unnamed pub known to neighbors as “The Green Door.” In 1977, Hayman

and friends bought the house and the pub.

“We were publishing ‘The Ear,’ a new music journal, at the time and we

decided to name the pub after it,” said Hayman. The city landmarks

commission didn’t allow new signage, so a coat of black paint covering

the curved neon tubes of the “B” in the pub’s BAR sign was sufficient

for EAR.

Although James Brown sold tobacco on the first floor, the shop has been a

pub for at least 150 years, said Hayman, who has a collection of whiskey

jugs found in the basement of the place. The records show there was a

bar in the building in 1835 and it was likely there for some years

before.

Hayman keeps a revolver, which he found several years ago tucked in the

flue of the second floor fireplace. “It’s a five-shot revolver made

around 1900,” he said. “I can imagine the circumstances when it was

hidden.”

Hayman, who is a principal in Odyssey Publications, a publishing firm with

offices in the James Brown House, is no longer active in the Ear Inn,

where he used to tend bar. Nevertheless, Martin Sheridan, who runs the

Ear, helps maintain the old house. It takes a lot of maintenance.

“We have crack gauges all over the walls,” Hayman said. “Whenever we have

engineers inspect the place they go, ‘Oh boy,’ and shake their heads.”

Hayman says he is worried most about the proposed redevelopment by Nino

Vendome of the adjacent property which shares a party wall with the old

house. Vendome first planned to build a 36-story tower designed by

Philip Johnson that would have cantilevered eight feet over the James

Brown House. The developer had a tentative agreement to replace plumbing

in the old house and provide space for a new exit and a kitchen

expansion for the Ear Inn as part of the redevelopment.

But Vendome failed to get a zoning variance for the building and now plans

an 11-story environmentally efficient building.

“When he builds it we’ll have to close and bring the whole building up to

code,” said Hayman. But help from the developer is not certain. “We may

not survive the construction unless we get help,” he said.

Andrew Berman, director of the G.V.S.H.P., agreed that the Vendome project

might threaten the James Brown house at 326 Spring St.

In a letter last week addressed jointly to Robert Tierney, Landmarks

Preservation Commission chairperson, and Patricia Lancaster, Department

of Buildings commissioner, Berman said, “The impending construction next

door at 328 Spring St. could easily pose a threat. Construction of this

planned 11-story building if not done with extreme care and regard for

the fragile state of the neighboring Ear Inn might easily damage or

undermine the landmark’s structural integrity.”

Berman called on the two agencies to work with Vendome and Hayman to

ensure that construction does not jeopardize survival of the house.

“After the building’s improbable and inspiring story of survival at this

location for almost 200 years, it would be tragic to see this historic

structure unnecessarily threatened now,” Berman said.

|

|

notes

|

(Adapted from “A Short History of Hudson Square” by the Friends of

Hudson Square.)

If you head south of Greenwich Village, west of

SoHo, and north of TriBeCa, you will find Hudson Square, the newest

district in New York City. This eclectic area is bordered by the

Hudson River to the west, Morton Street to the north, Canal Street

to the south, and Avenue of the Americas to the east. Although the

district is considered new, the community has a very rich history.

In 1705, Queen

Anne of England made a land grant of 215 acres to Trinity Church.

The Church Farm, to the north of the city proper, stretched from

Fulton Street to Christopher Street along the Hudson River, and was

mostly farmland and swamp. Although most of the farm was eventually

sold, Trinity is still the largest individual landowner in the

Hudson Square area.

By 1800, the community centering on Spring and Greenwich Streets was

a thriving market area known as Lower Greenwich. It was a working

class, racially mixed neighborhood south of the more affluent

Greenwich Village. Most of the buildings were Federal style

single-family homes with storefronts on the ground floor. Several

buildings still survive from this era, including the James Brown

House at 326 Spring Street (now home to the Ear Inn) as well as 486

and 488 Greenwich Street.

In the late 18th century, the area’s streets were named for now

historic figures such as the Dutch Governor Rip VanDam, then-mayor

of New York Colonel Varick, and William Houston, a delegate to the

Continental Congress. Richmond Hill, an elegant mansion that stood

at Charlton and Varick Streets, served as the headquarters for

General George Washington when he planned his battles in Long Island

during the Revolutionary War. It was later the home of John Adams,

Aaron Burr, and eventually John Jacob Astor, who subdivided the

estate and sold it for residential development in 1817.

Around this time, Trinity Church financed what is considered to be

New York’s first planned residential development surrounding a park

called Hudson Square, later known as St. John’s Park. The park stood

at what is now the entrance to the Holland Tunnel. The development

was similar in design to the Gramercy Park area. From the 1820s to

the 1830s, Hudson Square was the most desirable residential area in

the city.

With New York’s rapid expansion in the 19th century, the area was

completely connected to the city by the 1850s. Multiple dwellings

began to appear among the modest row houses in the working-class

neighborhood. Some of these tenements remain along Charlton, Broome,

and Spring Streets. Commerce grew in the area as well, with an

active market area blossoming and ships docking at the piers on

Canal and Clarkson Streets. Towards the end of the century, there

was an extensive trolley system along West Street, and New York’s

first elevated train ran up Greenwich Street.

|

|

By 1900, however the area was rapidly becoming a slum. Tenements had

replaced many single-family homes. Trinity Church sold some of the

land it owned in the area, and began turning much of it’s remaining

holdings to commercial and manufacturing space.

In the 1920s, printers moved into Hudson Square because of the lower

rents. At their peak, the printers in the area produced about a

quarter of all the printing in the country. Around this time, the

neighborhood was dug up for the installation of the Holland Tunnel.

The tunnel brought a significant amount of automobile and commercial

traffic to the area, which is now home to United Parcel Service,

Federal Express, and Wall Street Mail.

Today, the Hudson Square neighborhood has a mixture of high-rise

commercial offices, loft industrial buildings mostly converted to

office use, and low-rise residential buildings. Building sizes range

from a few quaint two-story structures to twenty-plus story

monoliths. An eclectic mix of ad agencies, architects, filmmakers,

publishers, printers, software developers, and web designers

populate the business district, along with interesting shops,

restaurants, nightclubs, and art galleries.

Within the last twenty years, the area has renewed its residential

flavor. Numerous buildings have been converted from industrial to

residential use. In addition, the Charlton King Vandam Historic

District between Sixth Avenue and Varick Street contain the

Federal-style row houses that were once common throughout the area.

They are the remnants of the subdivision of the Richmond Hill

estate, a memento of Hudson Square’s storied past.

|

THE WOMEN OF LISPENARD'S

MEADOWS

One of the most intriguing

and evanescent legends about the Lower Greenwich neighborhood is the

tale of the Jackson Whites. When the British occupied New York during

the American Revolution, they had to keep satisfied the thousands of

British and Hessian troops billeted here. The story goes that military

authorities turned to a man named Jackson, who sailed for England where

he either enticed or kidnaped 3,500 British prostitutes. He then packed

them in 20 leaky old boats and sailed for the American Colonies. One

vessel sank in mid-ocean, so Jackson sent another boat to the West

Indies where it picked up a load of replacements, all of African origin.

When the prostitutes landed in New York, they were marched to

Lispenard's Meadows, where they found a large stockade encircling a

group of crude huts that would be their home. When soldiers were ready

for fun, they repaired to Lispenard's Meadows and knocked on the

stockade door for a few hours with the "Jackson Whites" or the "Jackson

Blacks". In 1783, when the British hurriedly evacuated New York,

somebody ran to Lispenard's Meadows and unlatched the stockade door,

releasing the unfortunate women. About 500 of the prostitutes trekked

north up the Hudson, while the remainder somehow crossed the river and,

three-thousandstrong, marched west into New Jersey, finally settling in

the nearby Ramapo Mountains. They were supposedly the ancestors of a

group still living in those hills known as the Jackson Whites or the

Ramapo Mountain People.

|