|

New York Architecture Images- Lower Manhattan ELLIS ISLAND NATIONAL MONUMENT Landmark |

||||

|

architect |

Boring and Tilton (restoration 1991 Beyer Blinder Belle and Notter Finegold and Alexander. | ||||

|

location |

ELLIS ISLAND | ||||

|

date |

1898 | ||||

|

style |

Beaux-Arts | ||||

|

construction |

brick, limestone | ||||

|

type |

Government | ||||

|

|||||

.jpg) |

|||||

.jpg) |

|||||

|

|

|

||||

|

images |

|

||||

|

|

|

||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

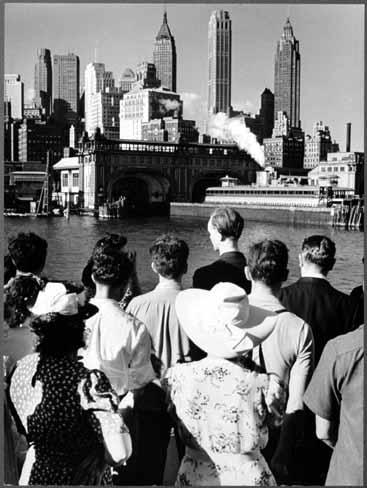

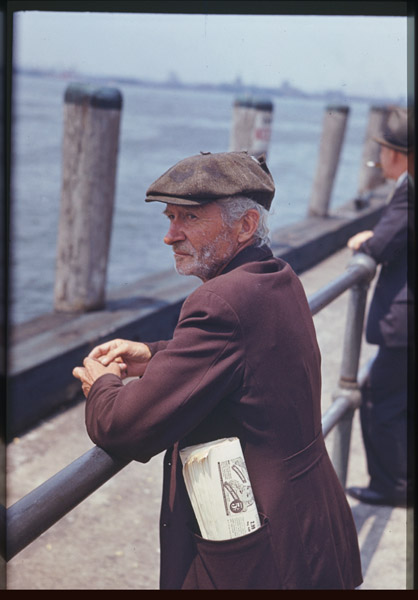

Seventeen million people entered the United States between 1892 and 1954 by passing through the immigration station on Ellis Island, the largest formal gateway to America. Today more than 40 percent of all living Americans can trace their roots to an ancestor who came this way. While the Statue of Liberty beckoned people to America's shores with her symbolic promises of freedom and a better life, Ellis Island embodied the reality of immigration during its second great wave from 1901 to 1914. The hopefuls who came Italy, Africa, and the French West Indies had their first taste of America at the island as they went through the somewhat tormenting and certainly bewildering process of acceptance. Officially closed by the government in

1954, and abandoned for years after, Ellis Island deteriorated under the

combined forces of nature and vandals. Considered surplus property

after its closing, the General Services Administration tried to sell it,

first to the state governments of New York and New Jersey and later to

private developers. These efforts failed because offers came in

lower than the appraised value. Furthermore, the prospect of

selling the historic landmass to a private developer for commercial

purposes was considered "cheap and tawdry" by many who were in favor of

setting it aside as a memorial to America's immigrants.

An architectural competition was held in September 1897, among the first under the Tarnsey Act, and a contract was awarded to the New York firm of Boring & Tilton in December 1897 for the design of the new Ellis Island Immigration Station. The government's design program called for a fireproof structure to accommodate the processing of 5,000 immigrants a day (up to 8,000 in an emergency). The main problem the architects had to address was circulation- -people needed to be processed with a minimum of confusion and delay as to avoid overnight stays. Designed to accommodate no more than 500,000 immigrants a year, the station was soon hopelessly overcrowded with yearly totals in the 700,000 range. The record high for Ellis Island was in 1907 when 1,004,756 immigrants passed through its doors. The numbers dropped off in 1914 with the beginning of World War I and remained low until the end of the war. With the "Red Scare" haunting the country, the U.S. Congress passed legislation in 1921 to check the rising tide of postwar immigration. The Main Building was designed in the French Renaissance style and composed of brick laid in Flemish bond and trimmed with limestone and granite "boasting quoins, rustification, and splendid belvederes." Triple-arch entrances that rose well into the second story marked the east and west sides in a grand style. Both Boring and Tilton attended the Ecole des Beaux Arts which may explain the influence of the French Renaissance style on the project. An analysis in Architectural Record (1902) pointed out the "bloated" character of the detailing and reasoned that the heavy handedness of the facade along with the chromatic scheme made the building easier to read from a distance, appropriate for one situated on an island in a busy harbor. The immense reception and inspection center was 388 feet long and 164 feet wide with heights of 57 feet to the balustrade and 126 feet to the dome finials. Upon entering the building, immigrants

mounted stairs leading to the second-floor Great Hall which served as

the waiting and processing room. A room impressive for its size- - 189

feet long and 102 feet wide with a 60-foot-high vaulted ceiling- -and

the abundance of large windows in the east and west walls. The

stairs leading to the Great Hall served as a medical treadmill. Doctors

waited at the top to check the breathing, posture, gait, and general

physical fitness of people as they made the climb. For many the

stairs took on a special meaning, for those feeble from sickness or old

age could be marked for rejection at that point.

The work of the Guastavino Brothers is well represented in buildings constructed during the first quarter of the 1900s in New York, Grand Central Station's Oyster Bar and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and across the country. The Guastavino's technique and materials are derived from Moors or older antecedents and perfected in the mid-nineteenth century. The basic idea is to build a thin dome or vault of more-or-less flat ceramic tiles in two or three overlapping layers laminated with a carefully proportioned quick-drying "cohesive" Portland cement. The amazing part is that nothing else in the way of additional support--no steel, no reinforcements, and usually not even a scaffold during construction. In the Great Hall, creamy white tiles are set in a herringbone pattern, distinctive to the Guastavinos, and aside from being beautiful, the vaulted tile ceiling is both fireproof and exceptionally strong. In the course of the current restoration, the ceiling only needed seventeen new tiles out of 28,282. General repairs, new construction, and landscaping were done on Ellis Island during the 1930s by the Works Progress Administration. The construction of a new fireproof ferryhouse in Art Deco style was one of the most interesting improvements, long with the creation of a large mural, Role of the Immigrant in Industrial America, (1935-36) by Edward Lanning, in he dining hall of the Main Building. The ferryhouse still stands but awaits attention as do many other buildings on Ellis Island. The mural was removed in he 1960s and reinstalled in a Brooklyn courthouse, but hopefully will be returned to Ellis Island to provide another record of the contributions made by immigrants. Ellis Island was designated part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument in 1965, administered by the National Park Service of the Department of Interior. Funds for the restoration of both Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty are being raised Privately by the Statue of Liberty Ellis Island Foundation, set up in 1982 by Lee Iacocca at the request of President Ronald Reagan. Funds are still being raised to meet the cost of the restoration, estimated at $150 million, and the centennial celebration in 1992. Today's visitors to Ellis Island, although unencumbered by bundled possessions and the harrowing memory of a transatlantic journey, retrace the steps of twelve million immigrants who approached America's "front doors to freedom" in the early twentieth century. Ellis Island receives today's arriving ferry passengers as it did hundreds of thousands of new arrivals between 1897 and 1938. In place of the business-like machinery of immigration inspection, the restored Main Hall now houses the Ellis Island Immigration Museum, dedicated to commemorating the immigrants' stories of trepidation and triumph, courage and rejection, and the lasting image of the American dream. During its peak years-1892 to 1924 Ellis Island received thousands of immigrants a day. Each was scrutinized for disease or disability as the long line of hopeful new arrivals made their way up the steep stairs to the great, echoing Registry Room. Over 100 million Americans can trace their ancestry in the United States to a man, woman, or child whose name passed from a steamship manifest sheet to an inspector's record book in the great Registry Room at Ellis Island. With restrictions on immigration in the 1920s Ellis Island's population dwindled, and the station finally closed its doors in 1954. Its grand brick and limestone buildings gradually deteriorated in the fierce weather of New York Harbor. Concern about this vital part of America's immigrant history led to the inclusion of Ellis Island as part of Statue of Liberty National Monument in 1965. Private citizens mounted a campaign to preserve the Island, and one of the most ambitious restoration projects in American history returned Ellis Island's Main Building to its former grandeur in September, 1990. Restoration of Ellis Island's Main Building

was the most extensive of any single building in the United States.

Often compared to the refurbishment of Versailles in France, the project

took eight years to complete at a cost of 156 million dollars. Opened

September 10, 1990, the Ellis Island Immigration Museum is New York

City's fourth largest and receives almost two million visitors

annually-twice as many as entered here in 1907, Ellis Island's peak

immigration year. The Immigration Museum's five permanent exhibits

contain 5,000 artifacts and hundreds of photographs which trace the

history of Ellis Island and the story of American immigration. The

museum also incorporates the American Immigrant Wall of Honor®, a

listing of over five hundred thousand immigrants' names. From anarchist

(Emma Goldman) to pianist Irving Berlin), from mobster ("Lucky" Luciano)

to mayor (New York's Abraham Beame), and from inventor (Igor Sikorsky)

to film star (Rudolph Valentino), immigrants added the threads of their

lives, whether good or bad, to the nation's fabric. Over 100 million

Americans, some forty percent of the country's population, can trace

their ancestry in the United States to a man, woman, or child who passed

from a steamship to a ferry to the inspection lines in the great

Registry Room at Ellis Island. Not surprisingly, the General Services

Administration described Ellis Island as "one of the most famous

landmarks in the world" when it tried to sell the island as surplus

Federal property in the 1950s. Along with a chunk of history, the buyer

would receive thirty-five buildings, two huge water tanks, the ferryboat

Ellis Island, thousands of feet of chain link fence left over from the

island days as an enemy and alien detention center. Advertised in

numerous newspapers, the island drew dozens of prospective bids.

Suggestions included an atomic research center, gambling casino, an

amusement park, a slaughterhouse, a womens prison, and "the perfect city

of tomorrow." No bid was high enough, however, and no sale was made. The

doors remained locked, the buildings empty. For ten years Ellis Island

stood vacant, subject to vandals and looters who made off with anything

they could carry, from doorknobs to filing cabinets. The building's

Beaux-Arts copper ornamentation deteriorated. Snow swirled through

broken windows, roofs leaked, and weeds sprang up in corridors, growing

in the footprints of anxious immigrants long gone. Ellis Island was

forgotten, swallowed by the fierce weather of New York Harbor. In

October of 1964 Stewart Udall, Secretary of the Interior for President

Lyndon Johnson, visited Ellis Island and recognized it as a vital part

of America's heritage. Udall urged President Johnson to rescue the

island and preserve a piece of America's past by placing the island in

the permanent care of the National Park Service. Ellis Island became

part of Statue of Liberty National Monument in 1965. Rebuilding the

seawall - to keep the island's landfill from slipping into the harbor -

became the first preservation task. Congress appropriated one million

dollars for its upkeep. The Registry Room's original plaster ceiling had been severely damaged in 1916 by the explosion of munition barges set afire by German saboteurs on New Jersey's Black Tom Wharf, a mile away. The ceiling was rebuilt in 1917 by Rafael Guastavino, a Spanish immigrant who had arrived with his little boy in the United States in 1881. Guastavino also brought with him ancient Catalonian building techniques, and together he and his son developed a self-supporting system of interlocking terra-cotta tiles that proved light, strong, fireproof, and economical. During the Registry Room's restoration, when the ceiling was inspected and cleaned, only seventeen of the 28,832 tiles originally set by the Guastavinos had to be replaced. As restoration progressed, workers discovered graffiti left by the immigrants, hidden beneath successive layers of paint on the building's walls. Scratched into the original plaster were names and initials, dating from 1900 to 1954, accompanied by poems, portraits, religious symbols, and cartoons of birds, flowers, and people. Some images were written in pencil, others in the blue chalk the medical inspectors used. Also inscribed were words of heartache. "Damned is the day I left my homeland," wrote one Italian hand, and in Greek sad and angry fingers scrawled, "Blast you America with your much money who took the Greeks away from their race." To save these telling accounts of the immigrants' frustration, joy, and perseverance, a fine arts conservator used methods developed to preserve the frescoes of Italy.

|

|||||

|

Ellis Island, at the mouth of the New York Harbor, was at one time the

main entry facility for immigrants entering the United States from

January 1, 1892 until November 12, 1954. It is wholly in the possession

of the Federal government as a part of Statue of Liberty National

Monument and is under the jurisdiction of the US National Park Service.

It is situated in New York City and Jersey City, New Jersey. Ellis Island was the subject of a border dispute between New York State and New Jersey (see below). According to the United States Census Bureau, the island, which was largely artificially created through the landfill process, has an official land area of 129,619 square meters, or 32 acres, more than 83 percent of which lies in the city of Jersey City. The natural portion of the island, lying in New York City, is 21,458 square meters (5.3 acres), and is completely surrounded by the artificially created portion. For New York State tax purposes it is assessed as Manhattan Block 1, Lot 201. Since 1998, it also has a tax number assigned by the state of New Jersey. History Ellis Island acquired its name from Samuel Ellis, a colonial New Yorker, possibly from Wales. TO BE SOLD By Samuel Ellis, no. 1, Greenwich Street, at the north river near the Jewish Market, That pleasant situated Island called Oyster Island, lying in New Bay, near Powle’s Hook, together with all its improvements which are considerable; also, two lots of ground, one at the lower end of Queen street, joining Luke’s wharf, the other in Greenwich street, between Petition and Dey streets, and a parcel of spars for masts, yards, brooms, bowsprits, & c. and a parcel of timber fit for pumps and buildings of docks; and a few barrels of excellent shad and herrings, and others of an inferior quality fit for shipping; and a few thousand of red herring of his own curing, that he will warrant to keep good in carrying to any part of the world, and a quantity of twine which he sell very low, which is the best sort of twine, for tyke nets. Also a large Pleasure Sleigh, almost new. —Samuel Ellis advertising in Loudon’s New York-Packet, 1778 The Ellis Island Immigrant Station was designed by architects Edward Lippincott Tilton and William Boring. They received a gold medal at the 1900 Paris Exposition for the building's design. The federal immigration station opened on January 1, 1892 and was closed on November 12, 1954, but not before 12 million immigrants were inspected there by the US Bureau of Immigration (Immigration and Naturalization Service). There are unsubstantiated estimates for immigrants processed there as high as 20 million. In the 35 years before Ellis Island opened, over 8 million immigrants had been processed locally by New York State officials at Castle Garden Immigration Depot in Manhattan. Entrance to the museum. Ellis Island was the first stop for most immigrants from Europe.Ellis Island was one of 30 processing stations opened by the federal government. It was the major processing station for third class/steerage immigrants entering the United States in 1892; it processed 70% of all immigrants at the time. Wealthy immigrants that traveled first class and second class would get automatic entry into the United States. Those who did not travel first or second class had to pass a six second physical examination. Those with visible health problems or diseases were sent home or held in the island's hospital facilities for long periods of time. Then they were asked 29 questions including name, occupation, and the amount of money they carried with them. Generally those immigrants who were approved spent from three to five hours at Ellis Island. However more than three thousand would-be immigrants died on Ellis Island while being held in the hospital facilities. Some unskilled workers and immigrants were rejected outright because they were considered "likely to become a public charge." About 2 percent were denied admission to the U.S. and sent back to their countries of origin for reasons such as chronic contagious disease, criminal background, or insanity.[1] Writer Louis Adamic came to America from Slovenia in southeastern Europe in 1913. Adamic described the night he spent on Ellis Island. He and many other immigrants slept on bunk beds in a huge hall. Lacking a warm blanket, the young man "shivered, sleepless, all night, listening to snores" and dreams "in perhaps a dozen different languages". After the 1924 "Quota Laws" placed restrictions on immigration, the United States government began processing immigrants in its embassies and consulates of the emigrant country. From 1924 until its closure Ellis Island was used only sporadically for immigration. It would be mostly used for detainees and refugees. Italians were detained, Japanese were interned, but the major group to be detained were German Americans during World War II falsely accused of being Nazis. As with all historic areas administered by the National Park Service, Ellis Island, along with Statue of Liberty, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966. Today Ellis Island houses a museum reachable by ferry from Liberty State Park in Jersey City, New Jersey and from the southern tip of Manhattan in New York City. The Statue of Liberty, sometimes thought to be on Ellis Island because of its symbolism as a welcome to immigrants, is actually on nearby Liberty Island, which is about 1/2 mile to the South. Ellis island was also known as "The Island of Tears" or "Heartbreak Island"[2] because of the 2% who were not admitted after the long transatlantic voyage. Other notable officials at Ellis Island included Edward F. McSweeney (assistant commissioner), Joseph Murray (assistant commissioner), Dr. George Stoner (chief surgeon), Augustus Frederick Sherman (chief clerk), Dr. Victor Heiser (surgeon), Thomas W. Salmon (surgeon), Howard Knox (surgeon), Peter Mikolainis (interpreter), Maud Mosher (matron), Fiorello H. LaGuardia (interpreter), and Philip Cowen (immigrant inspector). Prominent amongst the missionaries and immigrant aid workers were Rev. Michael J. Henry and Rev. Anthony J. Grogan (Irish Catholics), Rev. Gaspare Moretto (Italian Catholic), Alma E. Mathews (Methodist), Rev. Georg Doring (German Lutheran), Rev. Reuben Breed (Episcopalian), Michael Lodsin (Baptist), Brigadier Thomas Johnson (Salvation Army), Ludmila K. Foxlee (YWCA), Athena Marmaroff (Women's Christian Temperance Union), Alexander Harkavy (HIAS), Cecilia Greenstone and Cecilia Razovsky (National Council of Jewish Women). Noted entertainers that performed for detained aliens and US and allied servicemen at the island included Ernestine Schumann-Heink, Enrico Caruso, Rudy Vallee, Jimmy Durante, Bob Hope, and Lionel Hampton and his orchestra. Ellis Island is still open for touring. Immigration Immigrants arriving at Ellis Island, 1902Ellis Island would see a new immigrant entering the United States. More than 12 million immigrants passed through Ellis Island between 1892 and 1954. The first immigrant to pass through Ellis Island was Annie Moore, a 15-year-old girl from County Cork, Ireland, on January 1, 1892. She and her two brothers were coming to America to meet their parents, who had moved to New York two years prior. She received a greeting from officials and a $10.00 gold piece.[3] The last person to pass through Ellis Island was a Norwegian merchant seaman by the name of Arne Peterssen in 1954. After 1924 when the National Origins Act was passed, the only immigrants to pass through there were displaced persons or war refugees.[4] Today, over 100 million Americans can trace their ancestry to the immigrants who first arrived in America through the island before dispersing to points all over the country. An inaccurate myth persists that government officials on Ellis Island compelled immigrants to take new names against their wishes. In fact, no historical records bear this out. Federal immigration inspectors were under strict bureaucratic supervision and were more interested in preventing inadmissible aliens from entering the country (which they were held accountable for) rather than assisting them in trivial personal matters such as altering their names. In addition, the inspectors used the passenger lists given them by the steamship companies to process each foreigner. These were the sole immigration records for entering the country and were prepared not by the U.S. Bureau of Immigration but by steamship companies such as the Cunard Line, the White Star Line, the North German Lloyd Line, the Hamburg-Amerika Line, the Italian Steam Navigation Company, the Red Star Line, the Holland America Line, the Austro-American Line, and so forth.[5] Medical inspections Many immigrants were tested for mental problems, physical problems and other illnesses. Those who were wealthy did not have to take these exams. The symbols below were chalked on the clothing of potentially sick immigrants following the six-second medical examination. The doctors would look at them as they climbed the stairs from the baggage area up to the Great Hall. Immigrants' behaviour would be studied for difficulties in getting up the staircase in any way. Some only entered the country by surreptitiously wiping the chalk marks off or by turning their clothes inside out.[6] C - Conjunctivitis B - Back CT - Trachoma E - Eyes F - Face FT - Feet G - Goiter H - Heart K - Hernia M - Vaginal Infection N - Neck P - Physical and Lungs Pg - Pregnancy S - Senility Sc - Scalp (Favus) SI - Special Inquiry X - Suspected Mental Defect X (circled) - Definite signs of mental disease Notable immigrants Ellis Island immigrants attaining success in America include Lucky Luciano, Bob Hope, Irving Berlin, Knute Rockne, Ben Shahn, Arshile Gorky, Pola Negri, Anna Q. Nilsson, Claudette Colbert, Chef Boyardee (Ettore Boiardi), Erich von Stroheim, Felix Frankfurter, Father Flanagan, Joseph Stella, Arthur Tracy, Jule Styne, Pauline Newman, Irene Bordoni, Anthony Kiedis, Charles Atlas, Isaac Asimov, the Trapp Family Singers, Ezio Pinza, Ludwig Bemelmans, John Kluge, Hubert Fauntleroy Julian, Anzia Yezierska, Douglas Fraser, Sig Ruman, Michael Romanoff, Bela Lugosi, Charles Chaplin, Stan Laurel, Arthur Murray, and Max Factor. Museum The interior of the hall at Ellis Islands museum.The main building now houses a museum in addition to being a historic site. It is legally in New York state, while the southern part of the island, which holds the unrestored infirmary and hospital buildings, is legally part of New Jersey. There is a bridge between Ellis Island with Liberty State Park in Jersey City. It was built during the restoration of the island and heavy trucks went across it. In 1995 proposals were made to open it to pedestrians or to build a new bridge for pedestrians. They were defeated by two vested interests: the City of New York and the private operator of the only boat service to the island, the Circle Line. The supposedly inadequate bridge is still in use but closed to the public.[7] There is a "Wall of Honor" outside of the main building. There is a myth that it lists all of the immigrants processed there. It is actually a wall giving people the opportunity to make a donation to honor any immigrant into the United States. As of 2006, the wall lists 700,000 names spanning 400 years of immigration. Boston based architecture firm Finegold Alexander + Associates Inc, together with a New York architectural firm, designed the restoration and adaptive use of the Beaux Arts Main Building, one of the most symbolically important structures in American history. A construction budget of $150 million was required for this significant restoration. The building was opened to the public on September 10, 1990. In film Ellis Island attracted the imagination of filmmakers as long ago as the silent era. Early films featuring the station include Traffic in Souls (1913); The Yellow Passport (1916), starring Clara Kimbell Young; My Boy (1921), starring Jackie Coogan; Frank Capra's The Strong Man (1926), starring Harry Langdon; We Americans (1928), starring John Boles; Ellis Island (1936), starring Donald Cook; Gateway (1938), starring Don Ameche; and Exile Express (1939), which starred Anna Sten. More recently, the island was a scene used in Hitch, a motion picture starring Will Smith. He and Eva Mendes take a jet ski to the island and explore the building. Also, the movie, "Golden Door," culminates with scenes on the island. The IMAX 3D movie, Across the Sea of Time, about the New York immigrant experience, incorporates both modern footage and historical photographs of Ellis Island. Ellis Island as a port of entry to the United States of America is described in detail in Mottel the Cantor's Son by Sholom Aleichem. It is also the place where Don Corleone was held as an immigrant boy in The Godfather Part II, where he was marked with an encircled X. In the film X-Men, a UN summit held on the island is targeted by Magneto, who attempts to artificially change all the delegates present. The opening scene of Brother From Another Planet takes place on Ellis Island. A recent Italian movie called The Golden Door (directed by Emanuele Crialese) takes place largely at Ellis Island. Federal jurisdiction and state sovereignty dispute Overview before restorationOn October 15, 1965, Ellis Island was proclaimed a part of Statue of Liberty National Monument, which is managed by the National Park Service. The island is on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River. During the colonial period, however, New York had taken possession, and New Jersey had acquiesced in that action. In a compact between the two states, approved by U.S. Congress in 1834, New Jersey therefore agreed that New York would continue to have exclusive jurisdiction over the island. Thereafter, however, the federal government expanded the island by landfill, so that it could accommodate the immigration station that opened in 1890 (and closed in November 1954). Landfilling continued until 1934. Nine-tenths of the current area is artificial island that did not exist at the time of the interstate compact. New Jersey contended that the new extensions were part of New Jersey, since they were not part of the previous cession. New Jersey eventually filed suit to establish its jurisdiction, leading New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani dramatically to remark that his father, an Italian who immigrated through Ellis Island, never intended to go to New Jersey. The dispute eventually reached the Supreme Court of the United States, which ruled in 1998 that New Jersey had jurisdiction over all portions of the island created after the original compact was approved. This caused several immediate problems: some buildings, for instance, fell into the territory of both states. New Jersey and New York soon agreed to share claims to the island. It remains wholly a Federal property, however, and none of this legal maneuvering has resulted in either state taking any fiscal or physical responsibility for the maintenance, preservation, or improvement of any of the historic properties that make the island so significant in the first place. References ^ National Park Service: Ellis Island, retrieved January 12, 2006. ^ Davis, Kenneth (2003), Don't Know Much About American History, HarperTrophy, ISBN 0064408361 ("Isle of Tears" or "Heartbreak Island," p. 123) ^ Ellis Island Timeline. Retrieved April 21, 2007. ^ The Brown Quarterly, Volume 4, No. 1 (Fall 2000) -- Ellis Island/Immigration Issue ^ http://149.101.23.2/graphics/aboutus/history/articles/nameessay.html American Names / Declaring Independence, Marian L. Smith, INS Historian, US Citizenship and Immigration Services, last updated January 20, 2006, accessed May 22, 2007 ^ Ellis Island Chalk Marks. Retrieved April 21, 2007. ^ Setha Low, Dana Taplin, Suzanne Sheld (2005), Rethinking Urban Parks, University of Texas Press; chapter 4. ^ "My Grandmother Is the Greatest", http://www.knotmag.com/?article=1291, Knot Magazine, Matthew Sheahan, May 4, 2004 Ellis Island: Blocks 9019 thru 9023, Block Group 9, Census Tract 47, Hudson County, NJ; and Block 1000, Block Group 1, Census Tract 1, New York County, NY; United States Census Bureau Encyclopedia of Ellis Island by Barry Moreno (Greenwood Press, 2004) |

|||||