|

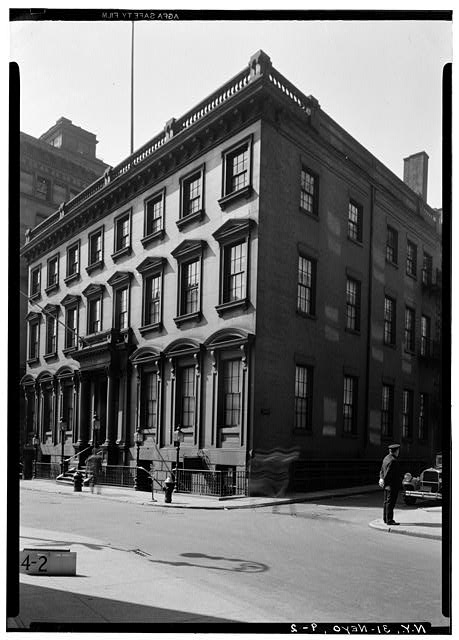

New York Architecture Images- Lower Manhattan INDIA HOUSE Landmark |

||||

|

architect |

Richard Carman | ||||

|

location |

One Hanover Square, between Pearl and Stone Streets | ||||

|

date |

1851-54 | ||||

|

style |

Renaissance Revival | ||||

|

construction |

|||||

|

type |

Office Building | ||||

|

|

|

||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

images |

|

||||

|

|

|

||||

Special thanks to the Museum of New York, www.mcny.org |

|||||

|

notes |

Originally built for the Hanover Bank, this brownstone structure

subsequently housed the New York Cotton Exchange and W. R. Grace & Co., and

today it functions as a club and restaurant. It exemplifies the second phase

of commercial construction in the city -- the expansion of counting houses

in the mid 19th century and the emergence of new commercial building types

such as banks. Carman's naive interpretation of a Renaissance palazzo (the

residential palaces of Italian banking families) is derived from English

interpretations of Italian palazzos. While American builders like Carman

turned to Europe for models of prestige architecture, they had little direct

exposure to or understanding of European stylistic traditions.

Only a few steps away, but in another world, is the mid-nineteenth century building at One Hanover Square. This brownstone building began life in the 1850s as the first home of The Hanover Bank. The structure today is one of the few pre-Civil War commercial buildings left in New York City. (The Hanover Bank merged with Manufacturers Trust Co. in 1961, and Chemical Bank merged with Manufacturers Hanover in 1991.) In 1914, the old Hanover Bank building was converted into a businessman's luncheon club named “India House”; one of the club's founders was JPMorgan employee Willard Straight.

|

||||

|

Hanover Square in the British Colonial Period by F.J. Sypher Hanover Square was a creation of British New York. During the Dutch period, New Amsterdam had its center at the southern end of Manhattan, near the main docks. The East River washed the shore at present-day Pearl Street (formerly Great Dock Street). Typical of the early structures in what is now Hanover Square was the house built in the mid-17th century by Burger Jorissen, on the west side of the square, at the corner of present-day William Street. Around the house were trees, gardens, and outbuildings, including, on the William Street side, a stillhouse, and a smithy. In front the windows looked out over a broad quay, dotted with trees, with the East River beyond. It must have seemed like a house on one of the canals of old Amsterdam. In 1664 the city came under British rule, and was named New York in honor of its proprietor, the Duke of York, later King James II. A few years later, in 1668, Burger Jorissen’s house was purchased as a residence by Thomas Lewis, a shipping merchant and alderman of the city. As New York grew toward the north and east, the city council surveyed the area (1691). By means of landfill, streets were extended, and even the waterfront moved one block east, to appropriately-named Water Street, opened 18 January 1694. The east side of the square then became available for building. In 1695, just after the death of Queen Mary II, the name “Great Dock Street” was changed to Queen Street. In the same year Abraham De Peyster, a merchant and prominent city official, built a large house in Queen Street. In bewigged finery he is vividly memorialized in the statue (1896, by George E. Bissell) that stands (or rather sits) now in Hanover Square. A resident on the west side of the square at about the same time was William Kidd, who assisted with the construction of the first Trinity Church; he is more widely remembered as “Captain Kidd.” The broad quay was now a city “square” (actually a triangle), with houses on three sides, and also in the lower part of the area in the middle (where the De Peyster statue is today). In 1714, in honor of the accession of George I, King of Great Britain and Ireland, and Elector of Hanover, the square was named Hanover Square. The city docks and their related commercial activity were by this time spreading northward as New York grew. As of 1712 the population of New York County was 5,840; by 1746 it had about doubled. In 1761, Gov. Cadwallader Colden estimated that there were about 2,000 houses in the city. As buildings downtown were converted to commercial use, people moved their residences further north. The house that had formerly been Thomas Lewis’ residence was later taken over by the printer William Bradford as a combined residence and printing-shop. There in 1725 he began publication of New York’s first newspaper, the New-York Gazette. In 1757, Hugh Gaine, bookseller and publisher, moved his headquarters to Hanover Square, which had become known as New York’s “printing house square,” an equivalent of the London square named after the King’s Printing House (1667). From Hanover Square, Queen Street led north toward an attractive residential neighborhood. At No. 156 Queen Street in 1752, William Walton, a prosperous merchant, built his spacious Georgian-style house, regarded at the time as the handsomest residence in the city. The location (site of the present-day 326-328 Pearl Street), was conveniently near his business office at Hanover Square. At about this time also, near the northern end of Queen Street, and not far from Walton’s house, the Parish of Trinity Church built its first chapel of ease, St. George’s Chapel, to accommodate a growing Anglican congregation, including families who lived at a distance from the mother church on Broadway at Wall Street. Robert Crommelin, an architect and member of the Trinity vestry, designed the new chapel in Georgian style. It stood at Beekman Street and Cliff Street. St. George’s Chapel was opened on the 1st day of July 1752. (In 1811 it became an independent parish, St. George’s Church; now at Stuyvesant Square.) Hanover Square was by then a center not only for publishing, but also for retail trade of all kinds. A contemporary newspaper advertisement mentions hats, clocks, looking-glasses, and East India goods. The location was near the docks (for supply of merchandise), and the north lay a fashionable residential neighborhood (for supply of customers). Another famous publisher in the area was James Rivington, at Queen Street. During the Revolution he published a loyalist newspaper, Rivington’s Royal Gazette. A distinguished resident of Hanover Square during the revolutionary period was Prince William Henry, later King William IV, known as “the sailor king.” He had begun his naval career aboard H.M.S. Prince George, under Admiral Robert Digby, who was sent to America in August of 1781. For a brief time in 1782 they lived at the Beekman house in Hanover Square. After the establishment of the United States, the New York City government changed a number of downtown street names, so as to reflect the new spirit of the nation. Queen Street became Pearl Street. Duke Street went back to being Stone Street. Crown Street became Liberty Street; King Street became Pine Street. The name “Hanover Square” was struck off the map, and the area officially became merely a part of Pearl Street. However, because of its long familiarity and prestige, “Hanover Square” continued in popular use, and it was officially restored in 1830. In 1787 the Bank of New York moved to 11 Hanover Square (it later moved to Wall Street). In 1828 Hanover Square was much improved when the buildings on the lower end of the triangular block in the center were removed. But then the great fire of 1835 destroyed the entire area. In subsequent years, as the square was built up again, it took on an aspect that can still be appreciated in surviving buildings, especially present-day India House, built in Italianate style in 1851-1854. It originally housed the Hanover Bank, founded in 1851 and named for its location on the square; in the same building were W.R. Grace & Co., and the New York Cotton Exchange. The positive associations of Hanover Square were also reflected in the name of the Hanover Fire-Insurance Company of New York. Late in the 19th century, the area literally fell under a shadow, when the Third Avenue Elevated Railroad went up (in the 1870s and 1880s). Hanover Square was one of the busiest stops on the line. Along Pearl Street, the columns and railroad tracks discouraged further development in the immediate area until after the el came down, in the mid-1950s. Consequently many older buildings on Pearl Street were spared when tall office buildings began to rise, starting in the 1890s. Today one can still, here and there, see something of what the neighborhood of Hanover Square looked like in the mid-19th century. But certainly the most flourishing period for Hanover Square was during the British colonial era, when it was one of New York’s prominent centers of commerce and culture. |

|||||

|

Streetscapes/India House, at 1 Hanover Square;

A Club Created With the Theme of World Commerce By CHRISTOPHER GRAY Published: June 30, 2002, Sunday JUST as it begins to repair its old brown walls at 1 Hanover Square, India House is readying an exhibit, ''Forged by Fire,'' that is to open in September with art and artifacts documenting both this unusual lunch club and also Hanover Square, which the club calls the first World Trade Center. At the same time a restoration campaign may present the downtown club with questions about which appearance it considers original. What is now Hanover Square, the narrow triangle bounded by William, Stone and Pearl Streets, was waterfront in the 16th century -- Pearl Street was originally Dock Street. As landfill pushed the shoreline farther away, the area filled up with shops and houses, and by the late 18th century it was developing into the principal business center of New York, with shops of prominent New York merchant families like Goelet, Hamersley, Broome, Bayard, Leroy and Clarkson. The Great Fire of 1835 swept a 20-block area around the square, but it was rebuilt quickly. According to research by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, the building that now contains India House was built in 1854 by the Hanover Bank, which had been organized in 1851. (It is not clear when the square got its name.) An early print shows the brownstone, Anglo-Italianate-style building with two stoops, as if it were a pair of unusually broad row houses, but it is clear from directories and other sources that it was occupied commercially. Various merchants, like Meadows T. Nicholson & Son, ''brokers in foreign exchange,'' are listed there in the 1869 directory. In 1871 the New York Cotton Exchange took over the building; its architect, Ebenezer L. Roberts, reconstructed parts of the interior, added a single columned doorway and placed a large clock face at the roof with the legend ''Cotton Exchange'' in raised letters of graduated size. At this point the structure took on the appearance of a single, large building, rather than a pair of small ones. On the interior, the Victorian-style stair baluster and the third-floor gallery, open to the second floor below, appear to date from the Roberts work. The Cotton Exchange moved in 1886, and it appears that the handsome, muscular fire escapes on the side-street elevations were added shortly after that, by the architect Julius Kastner. The shipping merchant William R. Grace took over the building, and by the 1890's someone had made a curiously retrospective change to the sign: a photograph at the New-York Historical Society shows that the sign had been amended to read ''Old Cotton Exchange.'' The building went through various uses -- at the turn of the 20th century it was the Haitian Consulate. Then, in 1914, India House came into being. The diplomat and writer Willard Straight and the president of United States Steel at the time, James A. Farrell, were convinced of the need for a social center for shipping executives and merchants concerned about America's place in world commerce. They chose the name India House to evoke the time when the Indies represented the focus of Western mercantile interests, and they hired the architects William Adams Delano and Chester Holmes Aldrich to make further changes to the building. Elite architects like Delano & Aldrich considered Victorian design, like the building's clunky parapet decoration, aesthetically unsalvageable, but they probably saw the underlying Anglo-Italianate design as something handsome, even if it was brownstone -- by that time the chocolate-colored stone was in complete disrepute. There are no early photographs of the new India House, but a contemporary rendering by Delano & Aldrich shows a facade stripped of its Victorian rooftop accretion, with window boxes and ornamental lanterns -- and, to judge from the rendering, a coat of whitewash. In 1924, the Delano & Aldrich firm was called back to expand the building southward into some older brick buildings on Pearl and Stone Streets. The architects added a large third-floor room, high and light, with a delicate oval skylight and the firm's signature, as well as unusual lighting fixtures, in this case a collation of shells and glass spheres. The column capitals and frieze in the room contain depictions of shells, fish and seahorses, another typically understated but playful touch. In 1926, writing in the magazine Architectural Forum, the architect Alexander B. Trowbridge called India House one of the most attractive clubs in New York, and in 1938 the magazine Antiques called it ''a kind of collector's paradise'' because of the ship models, paintings, prints and other artifacts that the club had assembled. It also described the exterior of the club as ''cream'' in color. The president of the club, George H. Gregor, says that India House has about 600 members, a number that has risen since it arranged for the restaurant Bayard's to take over the food service. Bayard's serves meals to club members in the daytime but then gets to use the building as a restaurant at night. Evening diners are offered a tour of the building, including its collections, which include a figurehead from an 1869 clipper ship, Glory of the Seas, which had sunk to barge use before it was burned for scrap metal in the 1920's. Margaret Stocker, the curator, says that India House has about 100 ship portraits in oil and 500 works on paper, from views of foreign harbors to portraits (including ones of Grace and Straight). On the ground floor, a large 17th-century Chinese silk portrait of a warrior has an astonishing frame, a gilt, deeply carved representation of a forest with gods, serpents and human figures. Over the atrium at the third-floor gallery a suspended wooden model of a merchant vessel, the Gladiator, swings slightly in the draft, as if rocking at anchor. The most unusual model, all white, is of the Royal Sovereign, one of Lord Nelson's fleet at his victory over the French and Spanish at the battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Superficially, it looks like ivory, but Ms. Stocker says it was made of soup bones, by a French prisoner of war at the time. THE clubhouse is filled with other maritime artifacts: a gilt eagle from the top of a New York pilot boat, and a stopped clock salvaged from a Spanish ship sunk by Admiral Dewey in Manila Bay in 1898; a large mahogany case of drawers with a plaque reading ''The Basic Commodities of Commerce,'' with glass-topped exhibit drawers of spices, furs, gums, resins, coals, petroleums, sugars and silks. This September India House will open ''Forged by Fire,'' an exhibit documenting Hanover Square's position as a nexus of world trade, from the time the Dutch West India Company used the area for its first docks. It will include an iron anchor found during excavations for the World Trade Center. Ms. Stocker is reevaluating the existing research on the club building; some conflicts between documents, and some peculiarities of the building, lead her to suspect that it may, in part, date from the fire of 1835, instead of 1854. By September the club's consultant, Walter Sedovic Architects, should be well along with initial tests on the facade, which is scheduled for a complete restoration. It has long been covered by a dull, brown stucco finish, a poor imitation of stone. Mr. Sedovic says that, unlike what occurs in most such projects, he and the club are committed to uncovering and restoring the original brownstone, patching with real stone where necessary. Most such projects accept brown-tinted stucco, even in cases where such a material would never be considered on a limestone, granite or marble building. But Mr. Sedovic, who has seen the original Delano & Aldrich drawing, which appears to show a white wash, is alert to the possibility that testing may present him with two restoration possibilities: a lighter-colored, painted facade of the 1910's, or a true brownstone facade of the 1850's. Published: 06 - 30 - 2002 , Late Edition - Final , Section 11 , Column 1 , Page 7 Copyright New York Times. |

|||||