|

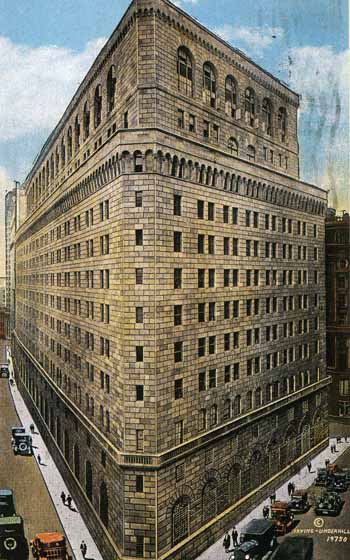

New York Architecture Images- Lower Manhattan FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF NEW YORK |

|

architect |

York and Sawyer (Samuel Yellin, wrought iron) |

|

location |

33 Liberty street at Nassau Street. |

|

date |

1920 |

|

style |

Romanesque Revival/ |

|

construction |

|

|

type |

Bank |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

notes |

Liberty Street entrance to the Bank flanked by fixtures crafted by metalworker Samuel Yellin. Yellin was awarded a $300,000 commission by the Bank to complete the wrought iron decorative work in 1920. Today the ironwork is priceless. (2001) The Fed's three-story high cash storage vault is the size of a football field. If filled with $100 bills, it can hold a total of $350 billion. The large cash vault is unmanned. Robots are used to transport cash. (1992) GUARDIAN OF THE GOLD The gold stored at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York is secured in a most unusual vault. It rests on the bedrock of Manhattan Island one of the few foundations considered adequate to support the weight of the vault, its door, and the gold inside 80 feet below street level and 50 feet below sea level. In the middle of 1997, the Fed's vault contained roughly 269 million troy ounces of gold (1 troy oz. is 1.1 times as heavy as the avoirdupois ounce, with which we are more familiar), representing 25 to 30 percent of the world's official monetary gold reserves. At the time, the vault gold's value was $11 billion at the official U. S. Government price of $42.2222 per troy ounce, or about $86 billion at the market price of $319 an ounce. At the current official U. S. Government price, one of the vault's gold bars (approximately 27.4 pounds) is valued at about $17,000. At a $319 market price, the same bar is worth about $127,000. Foreign governments and official international organizations store their gold at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York because of their confidence in its safety, the convenient services the Bank offers, and its location in one of the world's leading financial capitals. Confidence results from the Bank's being part of the Federal Reserve System -- the nation's central bank and an independent governmental entity. The political stability and economic strength of the United States, as well as the physical security provided by the Bank's vault, also are important factors. Convenience comes from the fact that the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, in addition to handling foreign financial transactions for the U. S. Department of the Treasury and the Federal Reserve System, executes many other financial transactions in the United States for foreign central banks. The attractiveness of the Bank's geographic location is that gold deposited in the trade and financial capital of the world's largest economy enables countries to engage in transactions of all sizes easily, quickly, and inexpensively. THE BANK STORES GOLD... The Bank stores gold in the form of bars that resemble construction bricks and stacks them on wooden pallets like those used in warehouses. To reach the vault, the bullion- laden pallets must be loaded into one of the Bank's elevators and sent down five floors below street level to the vault floor. The elevator's movements are controlled by an operator who is in a distant room and communicates by intercom with the armed guards accompanying the shipment. Once inside the vault, the gold bars become the responsibility of a control group consisting of representatives of three Bank divisions: Auditing, Vault Services, and Protection. A member of each division must be present whenever gold is moved or whenever anyone enters the vault. All bars brought into the vault are inspected and weighed. These steps are critical, because the weight and purity of a bar determine its value and acceptability in International transactions. A modern electronic balance scale weighs each bar to the nearest 1/1000 of a troy ounce. The vault control group verifies the weight, serial number, and purity measure stamped on each bar against an accompanying manifest AN INDISPENSABLE SECURITY SYSTEM Storing almost $86 billion of gold makes extensive security measures mandatory at the New York Fed. An important measure is the background investigation required of all Bank employees. Continuous supervision by the vault control group also prevents problems from arising by ensuring that proper security procedures are followed. The Bank and its vaults are guarded by the Bank's own uniformed protection force. Periodically, each guard must qualify with a revolver on the Bank's firing range. Although the minimum requirement is a marksman's score, most qualify as experts. In addition, the Bank's guards must be proficient with other weapons. Security also is provided by closed-circuit television monitors and by an electronic surveillance system that alerts the central guardroom when a vault door is opened or closed. The alarm system can signal guards to seal all security areas and Bank exits, which can be closed within seconds. The gold also is secured by the vault's design, which is a masterpiece of protective engineering. The vault is actually the bottom floor of a three-story bunker of vaults arranged like strongboxes stacked on top of one another. The massive walls surrounding the vault are made of a steel-reinforced structural concrete. There are no doors into the gold vault. Entry is through a narrow ten-foot passageway cut in a delicately balanced, nine-feet-tall, 90-ton steel cylinder that revolves vertically in a 140-ton, steel-and-concrete frame. The vault is opened and closed by rotating the cylinder 90 degrees. An airtight and watertight seal is achieved by lowering the slightly tapered cylinder three-eighths of an inch into the frame, which is similar to pushing a cork down into a bottle. The cylinder is secured in place when two levers insert large bolts, four recessed in each side of the frame, into the cylinder. By unlocking a series of time and combination locks, Bank personnel can open the vault the next business day. The locks are under "multiple control" no one individual has all the combinations necessary to open the vault. The weight of the gold - just over 27 pounds per bar - makes it difficult to lift or carry and obviates the need to search vault employees and visitors before they leave the vault. Nor do they have to be checked for specks of gold. Gold is relatively soft, but not so soft that particles will stick to clothing or shoes, or can be scraped from the bars. The Bank's security arrangements are so trusted by depositors that few have ever asked to examine their gold. ABOUT THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF NEW YORK The Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 11 other Reserve Banks, and the Board of Governors in Washington, D.C., make up the Federal Reserve System, the central bank of the United States. The Board of Governors, which serves as the System's governing body, consists of seven governors nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. One of the Governors is appointed by the President to be chairman, the highest post in the Federal Reserve. The chairman of the Board of Governors also is chairman of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the group of Federal Reserve officials who determine monetary policy. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York serves the Second Federal Reserve District (each of the 12 Reserve Banks serves a geographic District in the United States). The Second District encompasses New York State, the 12 northern counties of New Jersey, and Fairfield County, Connecticut, as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. The New York Fed and the other Reserve Banks supervise and regulate state-chartered banks that are members of the Federal Reserve System, and all bank holding companies and foreign bank branches and agencies based in their Districts. Each Reserve Bank provides services to depository institutions in its District and functions as a fiscal agent of the U. S. Government. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York has several unique responsibilities within the Federal Reserve System. Besides conducting open market operations (the buying and selling of U. S. Government securities in order to influence bank reserves and the availability of credit in the economy) to implement monetary policy at the direction of the FOMC, the Bank performs important international central banking functions. For example, the New York Fed engages in foreign exchange intervention on behalf of the U. S. Treasury and the Federal Reserve System. It also maintains relations with, and provides financial services for, foreign central banks. It is in conjunction with this role that the Fed serves as custodian for the gold reserves of foreign official and international accounts. Additionally, it invests the dollar reserves of those foreign customers in marketable U. S. Treasury securities. As of mid-1997, it held in custody over $630 billion of such securities.

|

|

January 10, 2005 On View for Public Coveting By GLENN COLLINS

|

|