NEW YORK -- The red awning still

hovers over the sidewalk at 19 West Street, claiming this

73-year-old Art Deco building as the official "Home of the Heisman."

But the canopy is dirty and faded. It's dwarfed by blue scaffolding.

And the doors to enter the building are boarded up.

Around the back, under another

discolored "Home of the Heisman" covering, a set of glass doors is

accessible. But they're filthy, slathered in 20 months of dirt and

fingerprints. Tentacles of cracks cascade down the soiled panes.

|

|

|

|

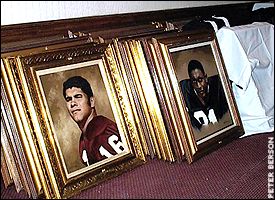

Heisman portraits will be placed in storage, but for now

lean against a second-floor wall. |

There was a time when this address was

the center of the nation's sports focus. One winter weekend each

year, a handful of the best college football players in the country

would hop out of limousines, walk into the building and hope to walk

out with the most prestigious individual award in sports.

But that will never happen again.

At least not here.

Plagued by financial troubles since

the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks leveled the nearby World Trade

Center, the Downtown Athletic Club turned over its mortgage last

week to this New York landmark, alleviating itself of escalating

debt but leaving the Heisman all but homeless.

There are now 60 days to clean up,

pack 68 years of history into cardboard boxes and move out. It isn't

easy. At the deeding of the property last week, DAC president Jim

Corcoran said he nearly backed out of the mortgage deal.

"My attorney said, 'What are you

doing?' " said Corcoran, who also serves as a senior vice president

at Morgan Stanley. "This is what everybody agreed on. This is what

we voted on. But it was hard to do. It felt like something was being

torn out of my heart."

The award, of course, will still go

on. Funded largely by the annual Heisman dinner and income generated

by the award's presenting sponsors, its future is as strong as ever.

The same Downtown Athletic Club personnel will be in charge. But the

club itself, which opened its doors in 1930 and five years later

created the award, will be all but gone.

Truth be told, things haven't been

the same since Sept. 11. Though the Heisman still had a home, the

DAC never reopened. Damage from the destruction of the World Trade

Center towers forced the club to move the 2001 Heisman ceremony to

the Marriott Marquis in Times Square. The Yale Club hosted the event

last year and will do so again this December.

"It's kinda like going to high school

somewhere and then going back 30 years later and there's a mall

there," 1973 Heisman winner John Cappalletti said. "That's what it

will be like. There's a lot of emotional ties to that place. Without

that building, it won't be the same."

|

|

|

|

The 73-year-old DAC building needs over $20 million in

renovations. |

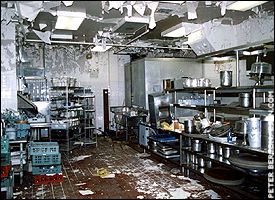

Yet if anybody could see the 38-story

building now, they'd understand. Paint peels away from nearly every

wall in every room. Some ceilings are pockmarked by giant holes and

brown watermarks, evidence of exploded water pipes. Other rooms,

which have barely been touched in two years, smell musty and stale.

The elevators only work sporadically, sometimes stranding passengers

between floors.

The Heisman room itself shows little

sign of change, except for the absence of the famed Heisman

portraits. They lean against a second-floor wall in an old banquet

room, waiting to be wrapped into black and white cloths and placed

into storage.

"Every time I open another box or

walk into another room, it's another flood of memories," said Rudy

Riska, the director of the Heisman foundation and a 43-year employee

of the Downtown Athletic Club. "That's probably what's the hardest."

When the club opened in 1930, it was

designed as both a fitness club and a social club for the elite.

Facilities included a 137-room hotel, seven banquet rooms, one

dining room, a state-of-the-art fitness center, a gymnasium, an

Olympic-sized swimming pool and squash, handball and racquetball

courts. At the time, the 12th-floor pool was the highest elevated

aquatics facility in the world.

The club peaked at 4,500 members in

the 1960s, but has seen a 78 percent decline since. In 1999, the DAC

narrowly avoided bankruptcy by selling the building to a Stamford,

Conn., investment firm a day before it was to be put on the auction

block.

The firm then turned around and sold

floors 1-13 -- essentially the Heisman room, the athletic facilities

and a couple of banquet rooms -- back to the DAC, allowing for a

rebuilding plan to be put in place. But just when the club was about

to finalize a deal with a club management company to run the

facility, plans changed when terrorists crashed two airliners into

the World Trade Center, which used to stand just two blocks away.

|

|

|

|

Once a gathering place for the elite, financial trouble has

forced the Downtown Athletic Club to close its doors. |

At the time, the upper floors of the

building were being gutted and all of the windows -- from the 14th

floor to the 38th -- were open for added ventilation. When the two

towers collapsed, dust and debris flooded the open rooms,

overwhelming the building's air ducts.

The building escaped structural

damage, yet still needed about $20 million to $30 million in

renovations. It never reopened. And each month that has passed,

Corcoran said, the club has lost about $100,000, falling further and

further into debt.

The club solicited help from its

members, but only 200 of the 900 letters it sent out were answered.

Later, the club invited 500 members to a financial meeting to

discuss the club's future. Sixty showed up.

"It's understandable -- people's

priorities changed that day," said Rob Whalen, coordinating director

of the Heisman Trophy and a former DAC athletics director.

"Companies were leaving downtown. Businesses were closing. People

were more concerned about losing loved ones and getting their lives

back together than they were about membership in a club."

And despite the deep pockets of

several former Heisman winners, the DAC had little interest in

reaching its hand out and asking for donations.

"I think a lot of them associate

themselves more with the trophy than the club," Whalen said. "And

for us to ask any of them to just hand a private club a couple

million just wasn't right."

So last month, in the same lobby that

Davey O'Brien, Doak Walker, Hopalong Cassady and Herschel Walker

once celebrated, 60 members of the club decided to turn over the

lease to the mortgage holders, erasing all outstanding debts.

"For a lot of us, that place was like

a second home," said 1969 Heisman winner Steve Owens. "Getting stuck

in the elevators, hearing the radiators popping, sitting in that old

bar -- that's what made it so special. But that place needed so much

work; it was just too expensive to keep up. So it's time to look to

the future."

For now, the four remaining employees

of the DAC, who also work with the Heisman, have 30 to 60 days to

vacate the building. Auctioneers and restaurateurs already are

combing the facility, inquiring about everything from ice machines

and dishwashers to dining room chairs and salt-and-pepper shakers.

The club has donated thousands of dollars in exercise equipment to

the Boys Club of New York and the New York Fire Department. Anything

Heisman related is being packaged and put into storage.

|

|

|

|

The DAC hopes its gym will host one final game to honor 11

members who died on 9-11. |

Riska already has opened a Heisman

office in a building next door. But before the club departs 19 West

Street for the last time, there are hopes for one final game. Though

the stairwells are dark, the paint is peeling and the club looks

more like a haven for the homeless than a clubhouse for Wall Street

execs, a handful of former club members want to organize a charity

basketball game to honor the 11 club members who died in the World

Trade Center attacks.

"If it's safe up there and we can get

it done, that's what we're going to do," Corcoran said. "It just

seems right."

There are even rumblings about

someday opening a new club in Battery Park City. A place with

state-of-the-art equipment and a Heisman museum. Perhaps the club

will be part of the new construction right at the Trade Center site.

Whatever the case, Corcoran is committed to keeping any new

facilities in downtown Manhattan, where it can be a vital part of

the city's post-Sept. 11 revitalization plan.

"You have to go to the bottom to come

back again," Corcoran said. "So that's what we're going to do --

let's just say the Heisman is on a road trip for a couple years

until we get it a new home."

Wayne Drehs is a staff writer for

ESPN.com. He can be reached at wayne.drehs@espn3.com.