|

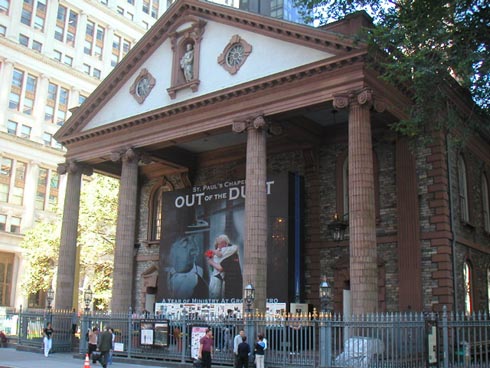

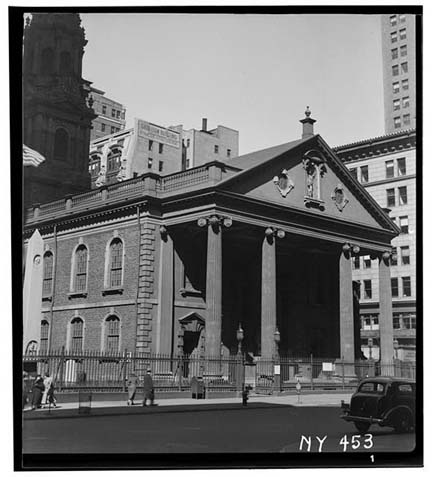

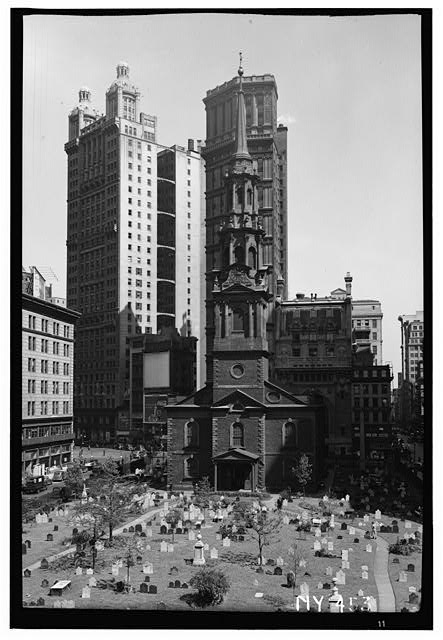

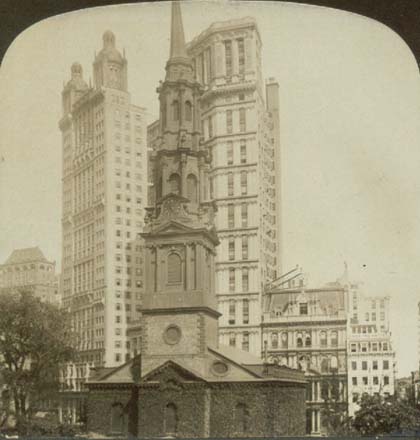

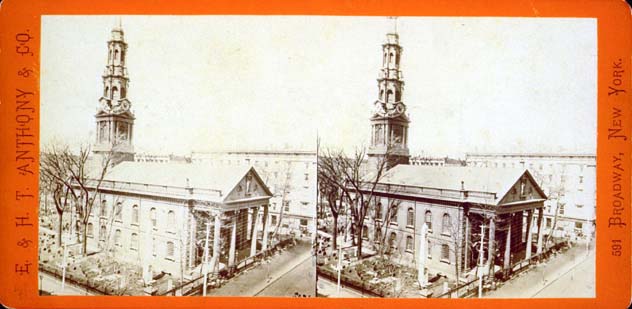

New York Architecture Images- Lower Manhattan St. Paul’s Chapel (Episc.) Landmark |

||

|

architect |

Andrew Gautier and James Crommelin Lawrence, and possibly Thomas McBean | ||

|

location |

Broadway (bet. Fulton and Vesey) | ||

|

date |

1766 | ||

|

style |

Georgian | ||

|

construction |

Built of Manhattan mica-schist with brownstone quoins, St. Paul's has the classical portico, boxy proportions and domestic details that are characteristic of Georgian churches such as James Gibbs' London church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, after which it was modelled. Its octagonal tower rises from a square base and is topped by a replica of the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates (c. 335 BC). | ||

|

type |

Church | ||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

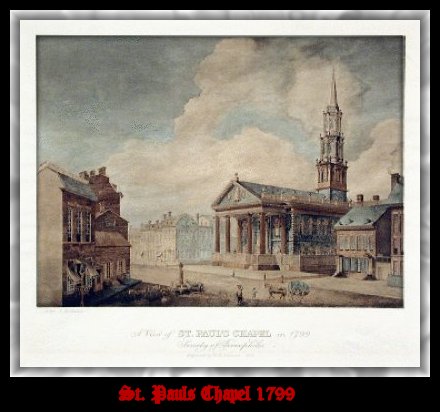

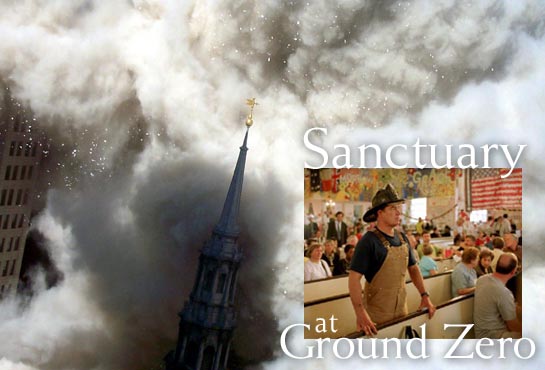

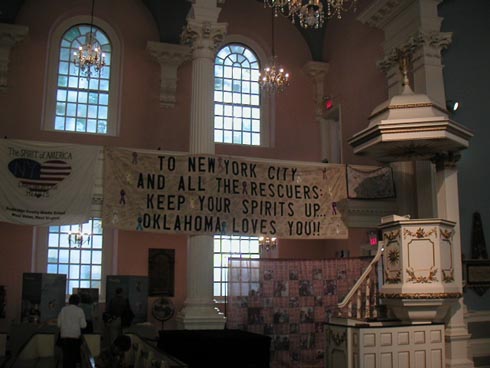

St. Paul's Chapel, at 209 Broadway, is an Episcopal chapel located on

Church Street between Fulton and Vesey Streets, opposite the east side

of the World Trade Center site in lower Manhattan in New York City. History and architecture A chapel of the Parish of Trinity Church, St. Paul's was built on land granted by Queen Anne of Great Britain, and Andrew Gautier served as the master craftsman. Upon completion in 1766, it stood in a field some distance from the growing port city to the south. It was built as a "chapel-of-ease" for parishioners who lived far from the Mother Church. Built of Manhattan mica-schist with brownstone quoins, St. Paul's has the classical portico, boxy proportions and domestic details that are characteristic of Georgian churches such as James Gibbs' London church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, after which it was modelled. Its octagonal tower rises from a square base and is topped by a replica of the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates (c. 335 BC). Inside, the chapel's simple elegant hall has the pale colors, flat ceiling and cut glass chandeliers reminiscent of contemporary domestic interiors. In contrast to the awe-inspiring interior of Trinity Church, this hall and its ample gallery were endowed with a cozy and comfortable character in order to encourage attendance. On the Broadway side of the chapel's exterior is an oak statue of the church's namesake, Saint Paul, carved in the American Primitive style. Below the east window is the monument to Brigadier General Richard Montgomery, who died at the Battle of Quebec (1775) during the American Revolutionary War. In the spire, the first bell is inscribed "Mears London, Fecit [Made] 1797." The second bell, made in 1866, was added in celebration of the chapel's 100th anniversary. The building was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1960. Early history George Washington, along with members of the United States Congress, worshiped at St. Paul's Chapel on his Inauguration Day, on April 30, 1789.[5] Washington also attended services at St. Paul's during the two years New York City was the country's capital. Above Washington's pew is an 18th-century oil painting of the Great Seal of the United States; adopted in 1782. The chapel contains several monuments and memorials that attest to its elevated status in early New York: a monument to Richard Montgomery (hero of the battle of Quebec) sculpted by Jean-Jacques Caffieri (1777), George Washington's original pew and a neo-Baroque sculpture called "Glory" designed by Pierre L'Enfant, the designer of Washington, D.C. The pulpit is surmounted by a coronet and six feathers, and fourteen original cut-glass chandeliers hang in the nave and the galleries. September 11, 2001 The Chapel was turned into a makeshift memorial shrine following the September 11 attacks, as seen in this photo taken January 12, 2002.After the attack on September 11, 2001, which led to the collapse of the twin towers of the World Trade Center, St. Paul's Chapel served as a place of rest and refuge for recovery workers at the WTC site. For eight months, hundreds of volunteers worked 12 hour shifts around the clock, serving meals, making beds, counseling and praying with fire fighters, construction workers, police and others. Massage therapists, chiropractors, podiatrists and musicians also tended to their needs. "Healing Hearts and Minds", an exhibit inside the chapel, consisting of a policeman's uniform covered with police and firefighter patches sent from all over the countryThe church survived without even a broken window. Church history declares it was spared by a miracle sycamore on the northwest corner of the property that was hit by debris. The tree's root has been preserved in a bronze memorial by sculptor Steve Tobin. The fence around the church grounds became the main spot for visitors to place impromptu memorials to the event. After it became filled with flowers, photos, teddy bears, and other paraphernalia, chapel officials decided to erect a number of panels on which visitors could add to the memorial. Estimating that only 15 would be needed in total, they eventually required 400. Rudolph Giuliani gave his mayoral farewell speech at the church on December 27, 2001. The Chapel is now a popular tourist destination since it still keeps many of the memorial banners around the sanctuary and has an extensive audio video history of the event. There are a number of exhibits in the Chapel. The first one when entering is "Healing Hearts and Minds", which consists of a policeman's uniform covered with police and firefighter patches sent from all over the country, including Iowa, West Virginia, California, etc. The most visible is the "Thread Project", which consists of several banners, each of a different color, and woven from different locations from around the globe, hung from the upper level over the pews. Services Interfaith service at St. Paul's Chapel on September 11, 2006.St. Paul's Chapel is a very active part of the Parish of Trinity Church, holding services, weekday concerts, occasional lectures, and providing a shelter for the homeless. On the evening of September 10, 2006, St. Paul's Chapel hosted a memorial service that was attended by President George W. Bush, Senator Hillary Clinton, Governor George Pataki, and Mayors Michael Bloomberg and Rudy Giuliani.[6], with the chapel holding additional services on the fifth anniversary of the September 11, 2001 attacks. Miscellanea St. Paul's Chapel, part of the Parish of Trinity Church, is the oldest public building in continuous use in New York City. The chapel survived the Great New York City Fire of 1776 when a quarter of New York City (then the area around Wall Street) burned following the British capture of the city in the Battle of Long Island in the American Revolutionary War Above the Governor's pew, which Governor George Clinton, the first Governor of the State of New York, used when he visited St. Paul's, are The Arms of the State of New York. Other historical worshipers have included: Prince William, later King William IV of England Lord Cornwallis, who is most famous in this country for surrendering at the Siege of Yorktown in 1781 Sir William Howe, Commander-in-Chief of British forces in America U.S. Presidents Grover Cleveland, Benjamin Harrison, and George H. W. Bush References ^ a b St. Paul's Chapel. National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service (2007-09-11). ^ National Register Information System. National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service (2006-03-15). ^ ["St. Paul's Chapel", October 11, 1975, by Patricia HeintzelmanPDF (312 KiB) National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination]. National Park Service (1975-10-11). ^ [St. Paul's Chapel--Accompanying photos, exterior, from 1975 and 1967.PDF (474 KiB) National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination]. National Park Service (1975-10-11). ^ Davidson, Roger H., Walter J. Oleszek (2006). Congress and Its Members. CQ Press, p. 13. ^ St. Paul's and the Three Georges. St. Paul's Chapel (September 10, 2006). |

|||

|

In 1766, New York City reached north to City Hall Park, then called The Commons. That year, Trinity Church provided St. Paul’s as a “Chapel of Ease” for its parishioners living on the northern border of the city near Fulton Street. The land beneath the church only a year earlier was a wheat field sloping to the Hudson River. St. Paul’s Chapel is today Manhattan’s only pre-Revolutionary church building and the building longest in public use. An architectural oddity is the church’s orientation: Built to face the Hudson River, its back is to Broadway, so that its original rear entrance is today its main entrance. The chapel was designed after St. Martin’s-in-the-Fields in London. Several architects had a part in its overall rendering, including Andrew Gautier and James Crommelin Lawrence, and possibly Thomas McBean, a protégé of James Gibbs, who designed the London church. Although threatened several times by fires in the early city, the church building’s original design is remarkably preserved. It was built of the native stone quarried from the churchyard known as Manhattan schist, and used with brownstone. The west end of the building on Church Street, now the rear entry, contains the church spire; while the east end, a very early replacement of the original rear entry, was designed as a carriage portico. Still, to the modern eye, this temple-front portico with giant Ionic columns is graceful and impressive. A niche above the portico holds an American Primitive hand-carved statue of Saint Paul. The spire was added in 1794 to the 1766 square masonry tower. The wooden steeple was painted white. The decorative trim of the brownstone walls of the building was also highlighted in white paint. In 1840, the steeple and trim were painted to match the brownstone and eventually the spire was coated in copper sheeting. The finial of the tower carries a gilt weathervane atop a replica of the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens. A handsome wrought iron fence erected in 1827 encircles the entire chapel and churchyard. The fence replaced a high brick wall that had enclosed the yard since 1805. In 1812, the brick wall had built into its north and southwest corners two houses for volunteer fire companies, reflecting the city’s constant anxiety over the danger of fire. In 1776, and again in 1832, over a thousand buildings burned in a single conflagration. The small firehouses in St. Paul’s wall contained Engine Companies 39 and 14, formed in 1812. Trinity Church, which had been built in 1696, burned in minutes in the great fire of 1776, its ruins were razed in 1789, and a new church built in 1790. The present Trinity Church was built in 1841. Its churchyard holds many graves of the Revolutionary Era, including Alexander Hamilton’s, Albert Gallatin’s, and William Bradford’s. St. Paul’s escaped a similar fate only barely, when the fire burned itself out in the empty lots bordering the churchyard north and west. British authorities commandeered churches of all denominations as refugee centers and to quarter troops, except for St. Paul’s and St. George’s, another Trinity chapel. Because of Trinity’s burning, St. Paul’s Chapel on Broadway took on primary importance to Anglicans of the city. However, the most scandalous association to St. Paul’s in the British occupation was the use of church-owned land to the west as a prostitution sector called, appropriately, the Holy Ground. Apparently, some of these neighbors attended services at the Chapel. A visitor to St. Paul’s in the day remarked, “This is a very neat church and some of the handsomest and best-dressed ladies I have seen in America. I believe most of them are whores.” During the British occupation in the Revolutionary War years, Generals Cornwallis and Howe attended services at St. Paul’s Chapel. On November 25, 1783, American General George Washington is supposed to have led a parade past St. Paul’s during his triumphal retaking of the city. Throughout the 19th century, New Yorkers gathered at the corner of Broadway and Ann Street to commemorate this storied event; although there isn’t conclusive proof it actually happened. A special Thanksgiving service was certainly held on April 30, 1789 in honor of Washington’s inauguration. Following the ceremony at Federal Hall, in which nobody remembered to bring a Bible, the new President and both houses of Congress walked to St. Paul’s. President George Washington, in the two years in which New York was the national capital, regularly attended St. Paul’s and his pew in the north aisle is preserved as a tourist attraction. The first image, an oil painting, of the Great Seal of the United States hangs over Washington’s pew. In 1799, a memorial service was held at St. Paul’s to mark George Washington’s death and James Monroe’s funeral was held there in 1831. The first Revolutionary War monument constructed in this country was in honor of Brigadier General Richard Montgomery who was killed at Quebec in 1775 and buried beneath the east porch of St. Paul’s. Benjamin Franklin commissioned the monument on behalf of the Second Continental Congress and the sculpture was erected in 1789 on the Broadway side of the church.

Today St. Paul's is again a Chapel of Ease as an entirely new residential district grows up around it. The churchyard is a shady oasis in the hustle and bustle of the Financial District and office workers and executives alike can be seen at lunch hour studying moss-covered tombstones. Daily services are conducted for business people and visitors. Regular concerts for the public are also held in the church on weekdays. St. Paul’s Chapel and Churchyard together were designated a New York City Landmark in 1966. Written by Doris Lane History When St. Paul’s Chapel was completed in 1766, it stood in a field some distance from the growing port city to the south. It was built as a “chapel-of-ease” for parishioners who lived far from the primary, or “Mother,” church. Today, St. Paul’s Chapel is Manhattan’s oldest public building in continuous use, and its remaining colonial church. Washington’s Pew George Washington worshiped here on Inauguration Day, April 30, 1789, and attended services at St. Paul’s during the two years New York City was the country’s capital. Above his pew is an 18th-century oil painting of the Great Seal of the United States, which was adopted in 1782. Directly across the chapel is the Governor’s pew, which George Clinton, the first Governor of the State of New York, used when he visited St. Paul’s. The Arms of the State of New York are on the wall above the pew. Among other notable historical figures who worshiped at St. Paul’s were Prince William, later King William IV of England; Lord Cornwallis, who is most famous in this country for surrendering at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781; Lord Howe, who commanded the British forces in New York, and Presidents Grover Cleveland, Benjamin Harrison, and George H. W. Bush. Architecture Andrew Gautier served as master craftsman, erecting a building typical of the Georgian Classic-Revival style, and resembling London’s St. Martin-in-the-Fields. St. Paul’s is constructed of Manhattan mica-schist with brownstone quoins; its woodwork, carving, and door hinges are handmade. The ornamental design of the “Glory” over the altar is the work of Pierre L'Enfant, who designed Washington, D.C. The “Glory” depicts Mt. Sinai in clouds and lightning, the Hebrew word for "God" in a triangle, and the two tablets of the Law with the Ten Commandments. The pulpit is surmounted by a coronet and six feathers. Fourteen original cut-glass chandeliers hang in the nave and the galleries. The organ case was built in 1804. On the Broadway side of the chapel’s exterior is an oak statue of St. Paul carved in the American Primitive style. Below the east window is the monument to General Richard Montgomery, who died at the Battle of Quebec during the American Revolutionary War. In the spire, the first bell is inscribed “Mears London, Fecit [Made] 1797.” The second bell, made in 1866, was added in celebration of the chapel’s 100th anniversary. The Extraordinary Ministry of St. Paul’s Chapel September 2001-May 2002 After the attack on September 11, 2001, which led to the collapse of the twin towers of the World Trade Center, St. Paul’s Chapel served as a place of rest and refuge for recovery workers at the WTC site. For eight months, hundreds of volunteers worked 12 hour shifts around the clock, serving meals, making beds, counseling and praying with fire fighters, construction workers, police and others. Massage therapists, chiropractors, podiatrists and musicians also tended to their needs. Today, St. Paul’s continues as an active part of the Parish of Trinity Church, holding services, weekday concerts, occasional lectures, and providing a shelter for the homeless. An associate for ministry at Saint Paul’s shares his thoughts on 9/11. On September 12, after having escaped the maelstrom of 9/11, I returned to Lower Manhattan to survey the damage to St. Paul’s Chapel—just yards away from where building 5 of the World Trade Center stood—and to find ways to be helpful in the rescue effort. At that point we assumed there would be many survivors. As I walked down Broadway from my apartment in Greenwich Village, my heart was pounding, not knowing what I might find. I assumed the chapel had been demolished. When I saw the spire still standing, I was overwhelmed. It took my breath away. Opening the door to enter St. Paul’s was an extraordinary experience; except for a layer of ash and soot, the building survived unscathed. Many proclaimed that “St. Paul’s had been spared.” It seemed clear to me that if this was true, it was not because we were holier than anyone who died across the street; it was because we now had a big job to do. Taking this challenge to heart, we set up a cold drink concession and hot food service four days later for the rescue workers, and men from our shelter, and many others, proudly flipped burgers at what came to be called the “Barbecue on Broadway.” The relief ministry at St. Paul’s was supported by the labor of three local institutions—the Seamen’s Church Institute, the General Theological Seminary, and St. Paul’s, in the parish of Trinity Church—and volunteers from all over the country. More than 5,000 people used their special gifts to transform St. Paul’s into a place of rest and refuge. Musicians, clergy, podiatrists, lawyers, soccer moms, and folks of every imaginable type poured coffee, swept floors, took out the trash, and served more than half a million meals. Emerging at St. Paul’s was a dynamic I think of as a reciprocity of gratitude.a circle of thanksgiving—in which volunteers and rescue and recovery workers tried to outdo each other with acts of kindness and love, leaving both giver and receiver changed. This circle of gratitude was infectious, and I hope it continues to spread. In fact, I hope it turns into an epidemic. There are so many stories that illustrate such selfless giving. One of the earliest, which continues to inspire me, is the story of the elderly African-American woman, probably in her 80s, who heard that a man working at ground zero had hurt his leg. So she got on the subway in the South Bronx and came all the way down to Lower Manhattan. She talked her way through the police lines, which at that time was no small feat, and came to St. Paul’s. Once inside she presented us with her own cane and then hobbled off. In that moment the universe became a little more generous. A poet once said “midwinter spring is its own season.” The period from the terrorists attacks to the end of the recovery efforts at ground zero was its own season, lasting 260 days. Although the calendar tells us that it lasted for three seasons—fall, winter, and spring—many of us have little recollection of any climate changes. We just got up, day after day, dressed accordingly, and went about the monumental task of trying to make sense out of absurdity, bring order out of chaos, and reclaim humanity from the violence that sought to make human life less human. This was also a season of remembrance as we mourned the loss of loved ones. It was a season of improvisation as we tried, often at our wit’s end, to respond to the needs emerging from these never before experienced acts of terrorism. It was a season of renewal as we sought to look toward a day when our commonalities will overcome our divisions, when compassion will overcome violence, and kindness will swallow up hatred. Ultimately, what began in hatred evolved into, in the words from that great song from the musical Rent, a “season of love.” It was a season in which people of love and goodwill, compassion and generosity, sought to practice the art of radical hospitality. The relief ministry at St. Paul’s has now come to an end. The chapel that once housed massage therapists, tired workers, and thousands of love notes colored carefully by schoolchildren and others has been closed for cleaning and restoration. I’m not quite certain what awaits this marvelous church when it reopens, but I do know that it was a rare privilge to take part in the work of these past months, and I have been forever changed by it. Now when I make my morning commute on the N or R subway to my office on Rector Street, I pass through Cortland Street Station, the station underneath the WTC site. Traveling through it, I see American flags, red tape, and signs that read, “Do not stop here.” My mind floods with memories, and all I can do is fold my newspaper and say a silent prayer for those who died there and for those who still suffer from the devastation. It’s a moment that is rather surreal as the past intersects with the harsh realities of the present and the hopes for a brighter, more humane future. — The Reverend Lyndon Harris St. Paul’s Chapel in Wake of WTC Disaster: “An Organic New Ministry Finds Us” By Kathryn Soman Two weeks after the attack on the World Trade Center and one week after the planned rebooting of his alternative worship services, the Rev. Lyndon Harris, pastor of St. Paul’s Chapel, charged with developing ministries there, found himself unable to seek out a new congregation – they’d been too busy finding him. For suddenly and unexpectedly, following

the September 11 disaster, as thousands of rescuers, recovery workers,

volunteers, journalists, and local residents converged near the junction

of Liberty and Church streets, St. Paul’s Chapel, directly in front of

the World Trade Center, became the focal point of respite from the

heart-and-backbreaking efforts now taking place at the site.

That Tuesday morning, Lyndon Harris reports, he’d been at the offices of Trinity Church Wall Street at 74 Trinity Place, when the first plane hit. “I heard a boom, and then smoke. We realized things were pretty bad,” he says, in his soft South Carolina cadence, “pretty soon.” Trinity’s preschool, housed next door, needed evacuating and Lyndon and other Trinity staff and clergy spent the first part of their ordeal leading all the children to safety before fleeing the building themselves. “When I left Trinity that morning,” he remembers, “I thought for certain that the chapel had been destroyed.” The next day, trudging to work through dust

and debris, Fr. Harris found the beautiful old building, one of the most

stunning examples of contemporary baroque architecture in the United

States, the place where George Washington had worshipped while

president, completely intact, without so much as a single window harmed.

“I can tell you,” he says solemnly, “that that was an emotional moment.

And then when I looked out at our graveyard which faces the Trade Center

and saw it covered in six inches of ash – well, I can promise you that

this graveyard is truly sacred ground now.”

With no phone service or electricity, on Friday, September 15, Fr. Harris was evaluating what services the chapel might offer a community in need when the first Seamen’s Church Institute volunteers arrived at St. Paul’s, carting food, clothing, and other much-needed supplies. Seamen’s Church, located at 241 Water Street in the South Street Seaport – an outreach ministry of the Episcopal Church to seafarers – organized the first relief efforts at St. Paul’s. Coordinating the activity of scores of volunteers recruited by Manhattan’s General Theological Seminary, the ministry enabled St. Paul’s Chapel to provide hundreds of hungry, tired, dirty, and often stressed-out rescue workers with everything from coffee and meals to eye drops, clean underwear, and a place to catch a little sleep. “We were grilling up hamburgers and hot dogs on four separate grills, 24/7, right there on Broadway,” Lyndon recalls with humor, “that is, until the Department of Health finally shut us down!” Strategically placed near what was now known as “Ground Zero,” St. Paul’s began functioning as a haven for the emergency crews and anyone else in need during those first terrible days. “People were eating, sleeping, and washing here,” says Fr. Harris, “and all this by candlelight and flashlight at first, until Verizon and Con Ed set up crude lamps for us so that people wouldn’t get hurt walking through the place.” On Saturday, September 22, Labor of Love, the national Episcopal relief effort based in Asheville, North Carolina, spearheaded by Bethany Anne Putnam, arrived, bringing with it its own group of volunteers, all of them experienced in offering support and guidance during a crisis and all of them skilled in disaster relief. That evening, electricity was finally restored to the chapel. “We actually had lights for the 6pm Sunday service,” Lyndon reports. With the help of Trinity Grants Program administrator Courtney Cowart, whose cousin, Martin Cowart, is a New York City restaurateur, St. Paul’s began receiving donations of food and even fully prepared hot meals from restaurants and vendors, including Dean & DeLuca and the Tribeca Grill. “That first week after the disaster,” Fr. Harris remarks, “we had a really fluid staff of volunteers working at the chapel, making calls for all sorts of donations. We had all kinds of people walking in, offering us their services on behalf of the rescue workers, everything from massage therapists to grief counselors to podiatrists.” And, as the first week passed and then the second, St. Paul’s continued to be a community resource, at once a practical comfort station and a place to regroup and recover spiritually. As rescue worker Luis Ramirez, a member of the NYPD’s 44th Precinct in the Bronx, says, reaching for a coffee and Krispy Kreme jelly donut while taking a break from his sixteen-hour shift: “I’m very surprised by all the services they’ve got for us here. It’s amazing,” he adds, looking around at the busy volunteers bustling about on St. Paul’s elegant portico. Long tables are piled high with fresh fruit – bananas, apples, oranges – and stacked with cans and cans of yellow cling peaches. Boxes overflow with candy, cookies, chips, power bars, gum, and, oddly, filterless Camel cigarettes. A young woman walks by, dressed in a pale gray t-shirt graphically proclaiming “Labor of Love” and “Inspiring Episcopalians to Assist Communities in Need.” Somehow, she’s juggling three one-gallon jars of Skinny Delight orange drink. Enormous cardboard boxes of donated foodstuffs keep arriving, marked “assorted pastries” or “sandwiches.” Two NYPD officers pass by, on their way back to duty, helmets filled with Juicy Fruit gum and assorted snacks. A tall gray-haired man, a volunteer in a white Red Cross polo shirt, marked Santa Monica, CA, asks, “Does anyone know where the mayonnaise is? It was here last night…” On Broadway, Con Edison is repairing the gas lines, while Verizon trucks pass in between police vehicles and fire trucks. Personnel from a slew of federal and city agencies are in evidence --FEMA, the NYPD, the Fire Transit and Parks departments, even the National Guard in camouflage. Sirens are going constantly. Luis takes another sip and says: “This place is great. I got a massage here a few days back… And the building itself, wow! The noise here on the street is completely overwhelming but in the chapel it’s so quiet. The doors don’t even have to be closed. You just walk in and it’s total calm, total peace.” For Father Harris, the past two weeks have been, as they have been for so many others, life-changing, with little time for reflection. “I was preparing to re-launch our new alternative worship services that we premiered this summer,” he recalls, “on Monday the 17th.” The services, combining jazz, gospel, the scriptural chanting known as Taizé, hip hop music and “sound painting,” designed to create a new congregation, to bring together a diverse mix of people of different ages, races, and ethnicities to worship with a thoroughly contemporary approach, are now -- temporarily -- on hold. Yet, as Lyndon points out, nonetheless, St. Paul’s Chapel now has “a brand new congregation, a wonderful, organic new ministry that we didn’t find; with the events of September 11th, they found us! The community we’re serving just came and got us. “At St. Paul’s, we’d been thinking we needed to reach out but, instead, people reached out to us. This experience has really taught me that one of the most important ministries of St. Paul’s during this crisis has been to accept the gifts of others, to accept their ministries, as well. Everyone wants to pull together, to work through our grief and nurture our hopes together. “I believe,” he adds, “that St. Paul’s wasn’t spared because it was holier than anyone who died there across the street, but because we are here to minister to and accept the ministry of our community. “You know, the other night, the Waldorf delivered dinner here for all the workers and volunteers. Sitting there, on the porch, a nice breeze blowing, eating fried chicken with some new-found friends – I felt like I was back down South. Here at St. Paul’s we’re just trying to keep on top of everything, finding community in our shared tragedy and offering that community a ministry of hospitality and support.” Posted October 2, 2001 |

|||