|

notes

|

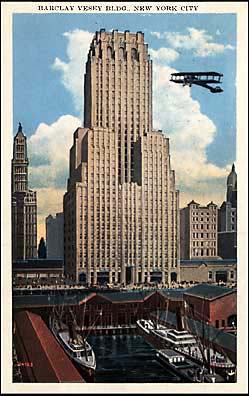

The first office building to be really influenced by Saarinen's design was

begun in 1923, the year after the competition, and it is called the

Barclay-Vesey Building because it is on Barclay and Vesey Streets. It was

the headquarters for the New York Telephone Company. It is an entire square

block in a section of the city that was not part of the grid of streets. So

it is not a rectangular block, it is on an oddly shaped trapezoidal block.

It was designed by the architectural firm of McKenzie, Voorhees & Gmelin.

This firm had been designing telephone company buildings since the

nineteenth century and although the firm had different names, it was

actually the same firm. So when this commission came to the firm, it was no

big deal. They gave it to an associate named Ralph Walker, a very talented

young associate, to design this building. Walker was very influenced by

Saarinen's design and was interested in how to turn the zoning law to his

advantage, and how to design buildings with dramatic setback massings that

would make the buildings an important and dynamic part of the skyline of New

York.

And so Ralph Walker designs one of the great buildings of the 1920s. It

has a solid horizontal base and then it has the soaring verticals with

window bays between vertical piers just as on Saarinen's design. It has very

dramatic setbacks marked by buttresses and sculpture until you reach the top

with its limestone detailing and its sculptural work. This building was

widely published and it captured the imagination of New Yorkers. It was also

very influential in getting other designers to use these kinds of forms on

the city's architecture. It was so successful that Ralph Walker became a

partner in the firm, which became known as Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker. And

Walker designed several other very important skyscrapers in the 1920s.

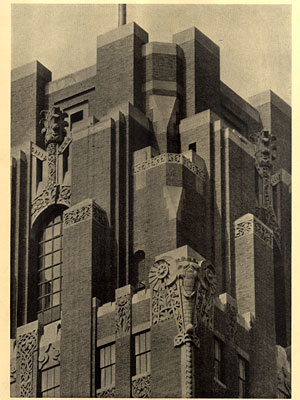

The top of the building, as you can see, is very dramatic. You were

supposed to be able to enjoy this building and experience its drama from

both close up and from far away. This building, which, when it was completed

in 1926, was right on the waterfront, now cannot be seen from the water

because of Battery Park City. It was in an area of relatively low-rise

commercial buildings, so this building towered over all the nearby buildings

in order to be visible both from the water and from the land. Its top would

capture your attention, and on the lower floors the ornament was very

complex so you could also enjoy this building from close up. Walker, like

Sullivan before him, wanted to use an ornamental vocabulary that was not

historically based, and he actually invented his own style of ornament,

which has this very complex foliate design in which are interspersed little

babies and animal heads. And even in the center, above the door, there is a

bell, the symbol of the telephone company.

From the AIA Guide:

"Distinguished, and widely heralded, for

the Guastavino-vaulted pedestrian arcades at its base, trade-offs for

widening narrow Vesey Street. The Mayan-inspired Art Deco design by

Ralph Walker proved a successful experiment in massing what was, in

those years, a large urban form within the relatively new zoning

'envelope' that emerged from the old Equitable Building's greed. Critic

Louis Mumford couldn't contain himself. A half century later, Roosevelt

Island's Main Street used continuous arcades as the very armature of

pedestrian procession. Why not elsewhere in New York to protect against

inclement weather and to enrich the architectural form of the street?

Why indeed, not next door, at 7 World Trade Center?"

Breathing new life into a

Manhattan landmark

By Michael Reis

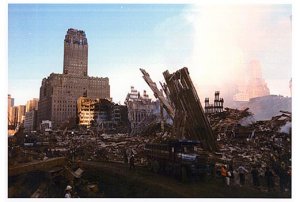

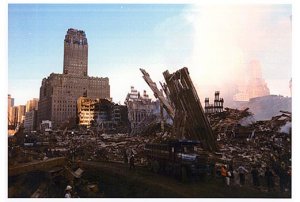

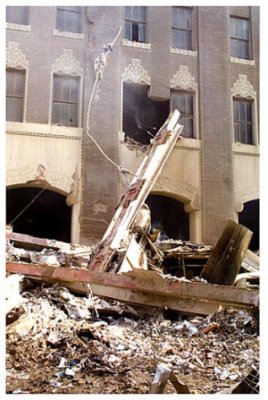

After two of its

facades were destroyed in the September 11 attacks, expert stonecarvers

have been called in to replicate the intricate stonework at the historic

Barclay-Vesey Building in New York City.

| In the aftermath of the

September 11 terrorist attacks, the damage to lower Manhattan was

not limited to the World Trade Center buildings. Many architectural

landmarks surrounding the complex were also damaged, some of them

severely. One of these structures was the historic Barclay-Vesey

Building, which is currently undergoing a restoration effort that

includes the re-creation of its intricately carved limestone

elements.

Originally built from 1923 to 1927 as the

headquarters for New York Telephone, the Barclay-Vesey Building

was significantly damaged when the fourth structure in the World

Trade Center complex -- Building Seven -- collapsed. When Seven

World Trade Center fell, steel girders from the building hit the

ground with such incredible force that they penetrated several

feet into the pavement. And as a result of the tremendous impact

of the collapse and resulting debris, two of the facades at the

Barclay-Vesey Building were brutally affected. The face of the

brick-and-limestone building had substantial holes that peered

out onto the destruction of the World Trade Center complex, and

much of the carved limestone was shattered well beyond repair.

The 32-story building had been designed by

McKenzie Voorhees & Gmelin Architects as the first Art Deco

skyscraper, with a height of nearly 500 feet. At the time of its

opening, its designers were awarded the Architectural League of

New York's gold medal of honor in 1927 for "fine expression of

the new industrial age." It was named the Barclay-Vesey Building

after the streets to its north and south.

Although much of the exterior is brick, the

feature elements of the facade are limestone, including large

cubic pieces as well as ornately carved panels. The carvings

depict a broad range of designs, with images of a bell -- New

York Telephone's icon -- as a recurring theme throughout.

|

|

Replicating

classic stonework

To reproduce the original limestone

carvings that were destroyed, Tishman Construction, the general

contractor, selected Petrillo Stone Corp. of Mt. Vernon, NY.

Owners Ralph and Frank Petrillo of Petrillo Stone Corp.

explained that their company has had a history of working with

Tishman and that its proximity to lower Manhattan made them a

nice fit for the job. "We spent days and days on the

scaffolding," explained Frank Petrillo, who added that

measurements are still being taken on a continual basis.

To handle such a challenging task,

Petrillo's carving team includes some of the New York area's top

artisans in the field, including Bob Carpenter, who trained as a

carver in Europe and heads the team; Michael Orekunrin, a master

stone carver who was educated in Nigeria and formerly worked at

the Cathedral of St. John the Divine for Cathedral Stoneworks;

and shop foreman Doug Breitbart. The team also includes carvers

and stonecutters Pooran Sanicharra, Ramesh Jodubar, Celine Canon

and Johnny Parbhu; sandblasters Alvin Green and "Scap" Sahadeo;

plannerman Fred Clayton and sawyer Joe Mangan. Alex Vays was the

project manager for Petrillo Stone Corp.

To rebuild what was lost at the

Barclay-Vesey Building on September 11, the carving team relied

on what had survived the attack. Although two of the structure's

facades were severely damaged, the stonework on the other two

facades remained largely intact. And fortunately, many of the

limestone designs that were destroyed on the building could also

be found on the extant facades.

The first step in replicating the stonework

was to take photographs and create molds of the existing

stonework at the building. "We wanted to simplify things as much

as possible," said Carpenter. "Every time I look at [the

facade], I see something else. I took 30 to 40 molds of

different areas, and we took pictures of everything. Then we

took those to Astoria Graphics, and they blew them up to full

size."

The images of the stonework are used to make

latex matting that outlines the surface designs of the

stonework. This matting is then placed over the slabs so they

can be sandblasted in the same way that stone monuments are

processed. A sand-blasting unit --purchased by Petrillo

specifically for the Barclay-Vesey Building restoration -- is

then used on the panels to achieve the necessary depth of the

designs. Then, the artisans use routers set at a low speed to

make sharper corners on the surface designs. By taking these

steps, the carvers are able to complete the detailing of what is

already dimensioned, and they do not have to spend an excessive

amount of time removing surface material.

"We wanted to keep everything as close to

the original as possible," Carpenter said. "The [original

carvers] were brilliant. From the street level, you really learn

the feel of the building. Even at two stories up, the detailing

of the panels is incredible." To further convey the character of

the original facade, the full-sized photos of the stonework are

set up in the shop for the carvers to reference while they work.

The limestone is quarried by Victor Oolitic

Stone Co. of Bloomington, IN, and it is cut into slabs by

Michael & Sons of Bloomfield, IN. While the thinner slabs are 5

or 6 inches in thickness, some of the pieces were much larger.

At the entrance, for example, pieces are as thick as 16 inches.

Before being delivered to the job site in

Manhattan, all of the finished pieces are classified by number

at Petrillo's shop so the installers can easily determine

exactly where each piece should be installed. In total, the

project will require 5,000 cubic feet of Indiana limestone, with

2,000 square feet of finished surface area.

In addition to the limestone, the project

also requires approximately 500 cubic feet of Stony Creek

granite for the base of the building. This stone was quarried in

Connecticut by Granicor, a Canadian firm, and it is supplied

through Furlong & Lee of New York.

The reconstruction of the Barclay-Vesey

Building is expected to be completed by September of this year.

Petrillo Stone Corp. is also responsible for the installation of

the new limestone and granite, and it is starting work on the

project this month with a crew of six to nine workers.

|

Michael Reis is the editor

of Stone World. /

Ties to Tradition

The skyscraper inspired both fear and awe.

( Rendering from the 1920's by Hugh Ferris)

The glories

of the machine age were not accepted unconditionally. Some beheld the

changes with misgivings and even fear. For many, the world was moving

too fast, and they struggled to come to terms with the changes and

recapture a sense of continuity with the past. To make sense of the

skyscraper and the machine age, writers of the time tried to historicize

and humanize the tall structures by placing them within an ancient

tradition and emphasizing the contributions and skill of the individual

laborer.

Some writers

of the 1930's did not treat the skyscraper as a break from the past, but

as another step in a continuing architectural tradition. These

comparisons not only calmed those that were afraid of the speed and size

that the modern age brought, but also justified the corporate gluttony

of the skyscraper in a time of economic depression.

"Were not even the

cathedrals extravagant, fantastic, and a little insane? Were they

not built less for use than in order that the proud citizen might

show what his community could do, and may not we be permitted to

fling our towers into the sky with the same wanton exuberance?"

("Skyscrapers")

"Just as the rulers and

great nobles of Europe, the princes of India, and the long line of

Chinese dynasts, used architecture to exalt themselves in their

publics' eyes, and as the surest monument to their achievements, so

do our industrial rulers act today" (Dewing, "Towers" 593).

"If the race itself is

a competition in advertising, so, in a manner of speaking , have

been all the competitions in tall buildings from the time when

Pharaoh vied with Pharaoh matching tomb against tomb, to the pious

rivalry of the cathedral builders, each seeking to raise a pointed

arch or a spire nearer to God" (Brock).

Alongside

these attempts to root the skyscraper in the past and justify its

extravagance was an even greater effort to humanize the skyscraper, to

make it a product and symbol of the people. In his essay "The Relation

of the Skyscraper to our Life"

Barclay-Vesey Building architect Ralph Walker believes that the

difference between the great structures of the past and the tall

buildings of the twentieth century was the human factor. "Where we have

a tall structure that has no relation to death like the pyramids, or to

religion like the Parthenon, which was placed on a high elevation to

emphasize the position of a goddess we have something of a human need."

The emphasis

on the worker is found consistently in the writings about the Chrysler

Building. In the promotional brochure the story of Walter P. Chrysler is

told as the idealization of the American dream, the rise of the common

laborer through hard work and ingenuity to the top of America's fastest

growing industry. More important than story of Chrysler is the

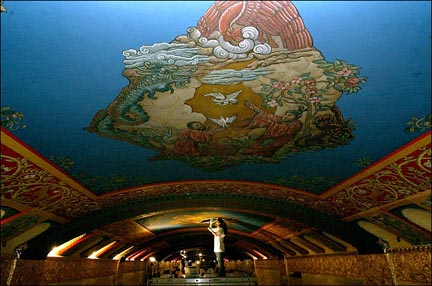

importance of the workers captured in the mural on the ceiling of the

lobby painted by Edward Trumball.

"Here was the base and

also the central theme: brawny man power, symbolic of the vitality

and the force typical of our age. Here, too, at the root of the

mural was the symbol that Mr. Chrysler wished to dominate the whole:

The power of the individual worker who labors with his hands, the

muscled giant whose brain directs his boundless energy to the

attainment of the triumphs of this mechanical era in that

never-ending struggle to bend the elements to his will" (15).

In

Fortune's four part special report called "Skyscraper" an entire

section was devoted to the workers and their tools. The articles assure

the reader that the worker has not been lost, just changed and that

"these are the new artisans."

"The

trouble with all the talk about the decay of artisan ship is that it is

true. It has always been true. It was true when the last wattle-weaver

died and they took to building houses of brick. And it will be true when

the tools and machinery of the contemporary arts are replaced by atomic

explosions...The master-workmen of our time drive steel to steel with

hammer strokes of air. But they still depend upon the judgment of hand

and eye. And their necks are still breakable" (27). "The

trouble with all the talk about the decay of artisan ship is that it is

true. It has always been true. It was true when the last wattle-weaver

died and they took to building houses of brick. And it will be true when

the tools and machinery of the contemporary arts are replaced by atomic

explosions...The master-workmen of our time drive steel to steel with

hammer strokes of air. But they still depend upon the judgment of hand

and eye. And their necks are still breakable" (27).

According to

Fortune, the lives of the steel workers were exciting, and

dangerous. Most of the writings created a portrait of the fine life of

the American steel worker. The following pictures were run with a full

article on riveting, quoted below.

|

"The

gang photographed on page 90 is Eagle's Gang, a veteran of the

Forty Wall Street [Manhattan Bank Building] job, reputed in the

trade to be one of the best gangs in the city. The gang takes

its name from its heater and organizer, E. Eagle, a native of

Baltimore. It is the belief of timekeepers, foreman, and the

leaders of other gangs that Mr. Eagle is a man of property in

his home town and indulges in the sport of riveting for

mysterious reasons. There are also myths about the gun-man and

the bucker-up, brothers named Bowers from some South Carolina

town. They are said never to speak. Even in a profession where

no man is able to speak, their silence stands out. The catcher

is George Smith, a New Yorker. There are no stories about

George" (28).

|

Writings

about the skyscraper also attempted to include not only those who worked

on the skyscraper but those who worked in and around it.

"The skyscraper, ever

concentrating more people above the same areas of ground, gives the

tenancy incalculable momentum and on the public's content with this

new way of living the success of the skyscraper depends" (Dewing,

"Towers" 590).

In a series

of articles in the North American Review of 1931, Arthur Dewing

discussed the public's architectural rights in relation to the

skyscraper. For the most part Dewing is against the skyscraper as "an

elevation of industry above mankind." However he also argues that every

citizen owns part of the tall buildings on the logic that if the

corporations mortgage the building from a bank and the bank depends on

thousands of common people with savings accounts then we all own some

little piece, however small, of the skyscrapers and should have a say in

their construction. It is a rather ridiculous argument by today's

standards, but it is representative of the conscious effort to empower

the people in the face of the rapidly expanding urban jungle.

Perhaps

nowhere is the effort to qualify and humanized the skyscraper more

clearly illustrated than in the display on the observation deck of the

Chrysler Building. Here the Chrysler Building is part of the past,

rising up out of a goat farm with the help of the hand made tools of

Walter himself. It is a fairy tale, told to those that needed to cling

to the traditions and ways of the past to usher in the marvels of the

machine.

"One of the

features of the observation floor will be an exhibition at the entrance

which will include a picture of the Chrysler Building site as it was

slightly more than fifty years ago--a goat farm, and another of the old

four-story buildings which were torn down to make way for the present

structure. Between these two pictures will be displayed the mechanics'

tools which Mr. Chrysler made with his own hands, and above this, as if

rising out of the tool box, will be a drawing of the new building"

("Finishing Touches").

The fairy

tale of individualism wrought by the machine carries over into the

marketing of Chrysler's automobiles. The ads emphasize the mythic

American individual, asking the prospective buyer to ignore the reality

of thousands of identical Chryslers rolling off the assembly line day

after day. (Click on the ads to see them enlarged.)

|

Was partly

damaged due to the Sept. 2001 terrorist attacks. The nearby

World Trade Center towers collapsed. |

|

- |

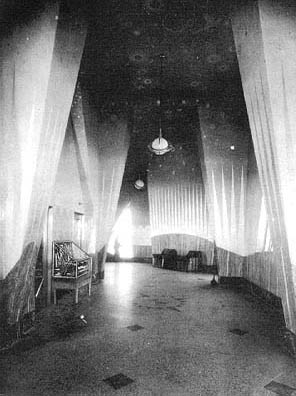

The lobby

goes through the middle of the building from Washington to West

Streets, with each entrance having its own address (Washington

Street is nowadays closed to motor traffic and paved). |

|

- |

The

152-meter building is considered to be the first Art Deco skyscraper

and its designers were also awarded the Architectural League of New

York's gold medal of honor for 1927 for fine expression of the new

industrial age. |

|

- |

The form

of the building was decided upon after studies of relation between

land cost and construction cost, a 32-storey design was chosen as

the most economical. |

|

- |

The

massive form with floors of 4,830 m² without any light courts was

possible because the telephone installations didn't require natural

light. |

|

- |

Drawing

from Saarinen's Chicago Tribune competition entry, the brick-clad

building is topped with a short, sturdy tower, with the vertical

piers ending on "battlements" on top and with sculptural ornaments

on the setbacks. |

|

- |

The

entrances are decorated with bronze engravings with a main theme of

bells, the symbol of the Bell Telephone Company. |

|

- |

A neo-Romanesque vaulted

arcade runs the whole length of the Vesey Street side. |

| - |

The lobby floor is covered

with bronze plates depicting the construction of New York's

telephone network, and the ceiling has frescoes with the theme of

the history of communication. |

| - |

The building occupies an

entire rhomboid-shaped block, and was built to accommodate office

space for more than 5,000 workers. |

| - |

The viewer is constantly

presented with two conflicting images of the tower: an

obliquely-angled mass and a steel-supported facade with angles sharp

as paper creases. |

|