|

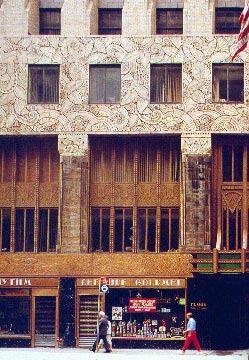

Built in 1927-1929 for Irwin S. Chanin, one

of the most notable developers in the city.

The 56-storey, 207.5 m tall Art Deco building is typically set back from

the limestone base. The top of the buff-brick tower sports elegant

buttressing decor that is enhanced by illumination at night. The corners

of the unornamented tower have protruding fins. At the lower end of the

building, bas-reliefs of terra-cotta depicting animals and leaf themes

run the whole length of lower facade.

The lobby was designed by Jacques Delamarre to celebrate the "self-made"

success of Irwin Chanin. The floor and screens are made of gilded

bronze, with modernist decor motifs of workers and transports by the

sculptor René Chambellan. Also the elevator doors and mailboxes are

elaborately decorated.

There was a private cinema theater on the 50th floor, as well as a viewing

roof, neither of which is accessible anymore. Also a bus depot with a

rotating turntable on the ground floor has been converted to other uses.

The Chanin Building is located at 122 east

42nd street and was completed in 1928, reaching a whopping height of 680

feet. This 56 story towers blunt buttressed crown became a symbol for

New York's crushing modernist drive. The buff-brick, limestone, and

terra-cotta tower is a fascinating synthesis of skyscraper styles. The

giant limestone buttresses at the base and crown are a conscience

reference to the skyscrapers stylistic origins in the gothic world. Its

giant 680 foot shaft rises uninterrupted for 22 stories above a series

od shallow setbacks. The thinness of this slab viewed from uptown or

downtown, creates a classic Art Deco setback silhouette. This is a two

in one solution which was copied also by the McGraw Hill Building, and

Rockefeller Center. The crowns reverse is lit at night so that the

buttresses are thrown into shadow, and the recesses are illuminated.

This building, built as leaseable office space, the building presents

itself as a high point of creation. A bronze frieze located at street

level depicts it as the sea and the tower as land. Another frieze on the

4th floor of the facade proclaims itself as a building of the 2oth

century.

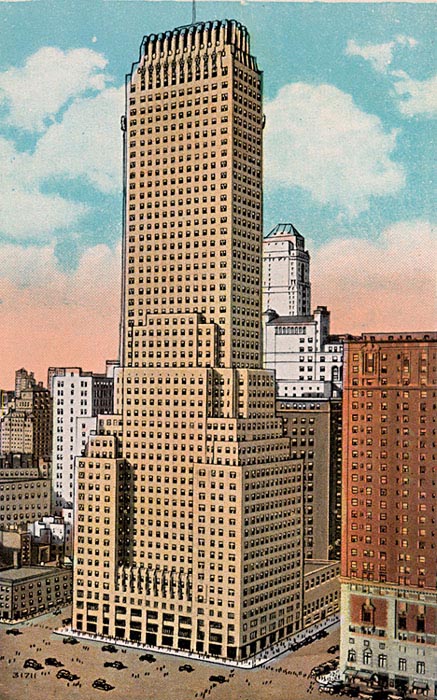

One of the first great examples of a

building that uses the French-inspired art-deco motifs is the Chanin

Building, located on the southwest corner of Lexington Avenue and

Forty-second Street. The architect, Irwin Chanin, had built Garment

Center loft buildings and a number of other buildings in New York. He

planned this one for his own offices and as a speculative venture—that

is, his private offices were on the top floor while the rest of the

building was open office space. Construction began in 1927.

Chanin trained at Cooper Union as an architect, but in 1927 he was not yet

registered. He eventually became a registered architect, but that year

he worked with the architectural firm of Sloan and Robertson. The firm

had worked on the Fred French Building and was involved in many

different office buildings in New York. Chanin worked with Sloan and

Robertson to come up with a spectacular design (which is very closely

modeled on Eliel Saarinen's plan for the Chicago Tribune Building) that

features a massive, horizontal base, soaring setbacks, strong verticals,

and buttresses. The building soars above the corner of Forty-second

Street and Lexington Avenue, right down the block from Grand Central

Terminal. And the light bounces off its façade. So this building was

highly visible.

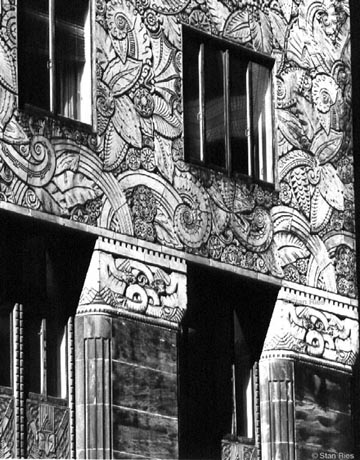

Besides being a spectacular ornament on the New York skyline, the building

is filled with French-inspired ornamental detail. Chanin had visited

Paris in 1925 and toured the Exposition Internationale des Arts

Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes. He was so inspired by it that when

he came back, he almost immediately started using these French-inspired

forms. A building like the Chanin was designed not only to attract your

attention from a distance but also to be both enjoyable and even

educational on the ground floor. And it was designed so that on the

lower stories it would attract not only pedestrians but also potential

tenants. The detail on this building is some of the most exquisite

art-deco ornament ever created in New York. There is a band of stylized

terra-cotta with curving and angular leaflike forms not unlike those on

Ferrobrandt's Cheney Silk Company doors. There is a frieze over the

storefronts that was meant both to entertain and to educate. It depicts

the theory of evolution. The frieze starts with amoebae and then, as you

move along, the amoebae become jellyfish, the jellyfish become fish, the

fish become geese, and yet there it stops. At that point, the theory

became too controversial.

There are also dynamic storefronts covered with zigzag patterns. This

design has come to be probably the most popular ornamental detail that

people are familiar with from art-deco buildings. But one of the

interesting things about the use of this pattern on such buildings is

that the zigzag almost never appears by itself. The angular, geometric,

mechanical zigzag is almost always overlaid with ornate, curving flower

petals. This combination of the mechanical and the natural overlaying

each other creates a very complex iconography on these buildings.

LOBBIES

The lobbies of this building are among the most interesting in the city.

They tell a story about New York as the city of opportunity. And the

city of opportunity was Irwin Chanin's life. Chanin was a poor immigrant

who was able to find success in New York because it offered him abundant

opportunity. He became one of its great developers and believed there

was opportunity for all in both intellectual and physical pursuits. With

its two main lobbies, one dedicated to each type of pursuit, the Chanin

articulates these beliefs. Both lobbies also house a stylized figure

that represents some aspect of either the intellectual or the physical

life. And below each figure is a bronze grille that represents this same

force in an abstracted way. So you see a figure striding forward atop

its abstraction below. This is probably the first use of abstract

ornament in an American building. Chanin designed it with the assistance

of the artist René Chambellan, who specialized in architectural

sculpture and was very popular in 1920s New York. The plaster figures

have this kind of stylized, almost hyper masculine form and they are

somewhat cubist in detail. It was a style that was very popular in the

1920s and the early 1930s. You can see the impact of European modernism

on these sculptures. And so in each one of these lobbies, there are four

of these groupings—four physical pursuits and four intellectual

pursuits.

Then you walk into the main lobby and find beautiful elevator doors that

use the same geese motif used outside. You could take one of the

elevators all the way up to the top floor, to Chanin's office. But

before you entered the office, you had to pass through a pair of bronze

gates that were every bit as much a part of the building's story. The

gates represented the greatness of the city, with its art and commerce

and its tremendous dynamism. You notice their gears, which signify the

industrial prominence of a great city like New York. And, at the top, in

the center, you see a violin that splits in half, indicating the

cultural life of the city. Then you spot these very dynamic bolts that

shoot through, indicating the city's dynamism. Or perhaps you might

interpret them as representing New York, the communication empire. Note,

though, that none of this would have been possible without a great deal

of money and so these gates rest on piles of gold coins. So he designed

these gates to sum up for you what the city was all about, before you

entered his private offices, which were also elaborately designed with

art-deco details.

Andrew Dolkart |