|

New York

Architecture Images- Midtown Andy Warhol’s “Factory” |

|||

|

location |

19 E32 and 22 E33, Between Park and Madison | |||

|

images |

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

||||

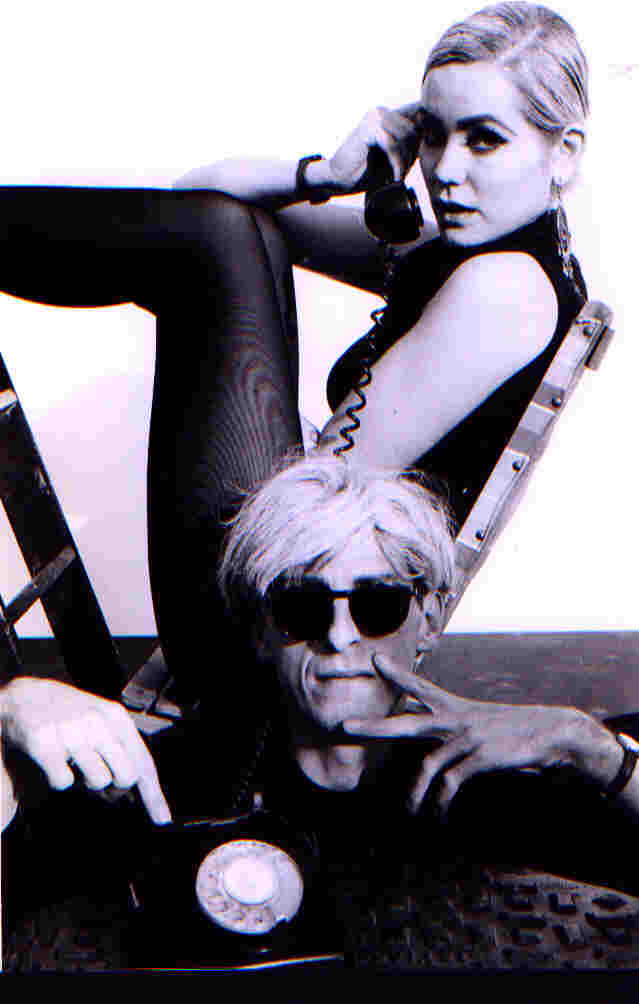

Andy Warhol's FactoryI had remarked that the film I Shot Andy Warhol and Bill Morgan's section for Greenwich Village and Chelsea in the guidebook further raise the question of whether or not living quarters classify as a "Great Good Place". According to Oldenburg's definition they do not since the establishment must be seperated from one's home and job. Sally Banes however offers us another perspective. In the second chapter of Greenwich Village 1963 (page 36) Banes discusses Andy Warhol's factory and states that while people actually lived there others came just to "hang out" (some to drugs, others to listen to music, while still others talked or just came to meet people. "By the late Sixties it was famous as a fashionable scene. The Factory was both site and symbol of the alternative culture's disdain for the bourgeois ethic, from work to sex to control of consciousness-----a sanctified space where leisure and pleasure reigned". From this Banes challenges Oldenburg's definition, while the Factory met some of Oldenburg's criteria it also opposed others. If we accept Banes implication that living quarters can be a "Great Good Place" we must also remember what various apartments, condos, townhouses, rooms for rent meant to the Beats particularly in light of Morgan's earlier readings in the section of Columbia Univeristy. Lynette Erbe |

||||

Warhol's Last Factory

Warhol used the space as a studio as well as for the headquarters of the once cutting-edge Interview magazine. After Warhol died, the contents of the Factory were sold off at an auction for a reported $25 million, most of which went to charity. The building isn't the only Warhol real estate on the market: Eothen, the Montauk, Long Island, property Warhol bought with partner Paul Morrissey, is for sale for $50 million and earned a spot on Forbes.com's list of the most expensive homes in America. |

||||

|

notes |

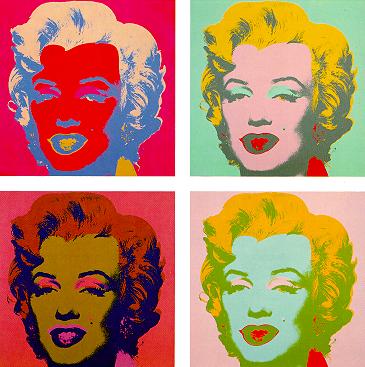

What for years

modernists

had deliberately ignored or contemptuously spurned, Warhol embraced. As

appropriated mass-culture images—such as his Turquoise Marilyn

(1962)—his "art" was indistinguishable from advertising—meaning it was

crass and pedestrian—and thus lampooned the modern emphasis on noble

sentiment and good

taste. No doubt Warhol's comments about art, that it should be

effortless, that it's a business having nothing to do with

transcendence, truth, or sentiment, also infuriated detractors. -- Alan

R. Pratt

http://faculty.erau.edu/pratta/warhol/critics.htm

|

|||

|

||||

|

"I'd prefer to remain a mystery. I never like to give my background and,

anyway, I make it all up different every time I'm asked."

He was one of the most enigmatic figures in American art. His work became the definitive expression of a culture obsessed with images. He was surrounded by a coterie of beautiful bohemians with names like Viva, Candy Darling, and Ultra Violet. He held endless drug- and sex-filled parties, through which he never stopped working. He single-handedly confounded the distinctions between high and low art. His films are pivotal in the formation of contemporary experimental art and pornography. He spent the final years of his life walking around the posh neighborhoods of New York with a plastic bag full of hundred dollar bills, buying jewelry and knick knacks. His name was Andy Warhol, and he changed the nature of art forever. Andy Warhol's exact birth date is unknown, though one can assume it is between 1927 and 1930. What is known is that he was born to Czechoslovakian immigrant parents in Forest City, Pennsylvania. He was a shy quiet boy, leaving high school to attend the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh. He received his bachelors of fine arts degree from there in 1949, and headed immediately to New York. In New York, Warhol found design jobs in advertising. Before long he had begun specializing in illustrations of shoes. His work appeared in GLAMOUR, VOGUE, and HARPER'S BAZAAR. In the mid-'50s he became the chief illustrator for I. Miller Shoes, and in 1957 a shoe advertisement won him the Art Director's Club Medal. During this time, Warhol had also been working on a series of pictures separate from the advertisements and illustrations. It was this work that he considered his serious artistic endeavor. Though the paintings retained much of the style of popular advertising, their motivation was just the opposite. The most famous of the paintings of this time are the thirty-two paintings of Campbell soup cans. With these paintings, and other work that reproduced Coca-Cola bottles, Superman comics, and other immediately recognizable popular images, Warhol was mirroring society's obsessions. Where the main concern of advertising was to slip into the unconscious and unrecognizably evoke a feeling of desire, Warhol's work was meant to make the viewer actually stop and look at the images that had become invisible in their familiarity. These ideas were similarly being dealt with by artists such as Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, and Robert Rauschenberg -- and came to be known as Pop Art. Throughout the late 1950s and 1960s, Warhol produced work at an amazing rate. He embraced a mode of production similar to that taken on by the industries he was mimicking, and referred to his studio as "The Factory." The Factory was not only a production center for Warhol's paintings, silk-screens, and sculptures, but also a central point for the fast-paced high life of New York in the '60s. Warhol's obsession with fame, youth, and personality drew the most wild and interesting people to The Factory throughout the years. Among the regulars were Mick Jagger, Martha Graham, Lou Reed, and Truman Capote. For many, Warhol was a work of art in himself, reflecting back the basic desires of an consumerist American culture. He saw fame as the pinnacle of modern consumerism and reveled in it the way artists a hundred years before reveled in the western landscape. His oft-repeated statement that "every person will be world-famous for fifteen minutes" was an incredible insight into the growing commodification of everyday life. By the mid-'60s Warhol had become one of the most famous artists in the world. He continued, however, to baffle the critics with his aggressively groundbreaking work. Putting aside much of the "pop" imagery, he concentrated on making films. His films, as his paintings had been, were primarily concerned with getting the viewer to look at something for longer than they otherwise would. Using film, Warhol could control the viewer's attention. One of his most famous films, SLEEP (1963), was eight hours of the poet John Giorno asleep in his bed. Warhol's movement into film directing and production brought him into contact with dozens of artists and actors interested in working in The Factory. One of these was actress and writer Valerie Solanas, who had for some time been trying to get Warhol to produce one of her scripts. In 1968, in anger at Warhol's disinterest, Solanas (the founder and only member of S.C.U.M., the Society for Cutting Up Men), shot and nearly killed Warhol. During Warhol's extended convalescence he began to work on a new mode of art. Considered his "Post-Pop" period, the images were primarily portraits of living superstars. Throughout the '70s and '80s, Warhol produced hundreds of portraits, mostly in silk screen. His images of Liza Minnelli, Jimmy Carter, Albert Einstein, Elizabeth Taylor, and Philip Johnson express a more subtle and expressionistic side of his work. During the final years of his life, Warhol became the hero of another generation of artists, including Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Francesco Clemente. Their work represents a continuation of an artistic revolution begun by Andy Warhol. On February 22, 1987, Warhol died of heart failure at his home in New York. Many suggested it was a poorly performed minor surgery he had had earlier that day, while others believed it was due to the general weakening of his body after the shooting. What remains certain is that during the sixty years of whirlwind and mystery that was Andy Warhol's life, the art world (and the world at large) became a more fun and interesting place. |

||||

|