|

New York

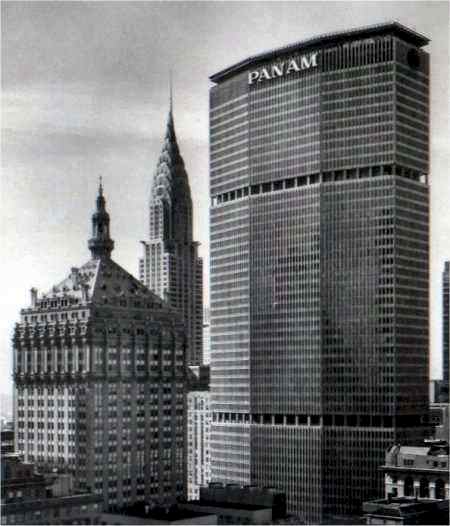

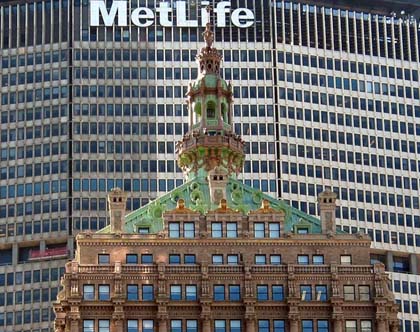

Architecture Images- Midtown Met Life Building (formerly the Pan Am Building) |

|

architect |

Emery Roth & Sons with Walter Gropius and Pietro Belluschi as design consultants |

|

location |

200 Park Ave. |

|

date |

1963 |

|

style |

Brutalism |

|

construction |

Developer: Erwin S. Wolfson Height 808

ft (246 m), 59 floors eight-storey, granite-clad base The concrete walls of the tower are interrupted by two colonnaded openings on the facade, at 21st and 46th floors, behind which the technical equipment is located. |

|

type |

Office Building |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

images |

|

|

|

|

|

notes |

In 1954, according to James Trager in his 1990 book, "Park Avenue, Street of Dreams (published by Atheneum), William Zeckendorf, then head of Webb & Knapp Inc., proposed an 80-story, 4.8-million sq. ft. tower, 500 feet taller than the Empire State Building, to replace Grand Central Terminal. The sensational, pinched-cylinder design by I. M. Pei, perhaps his finest, was, however, quickly abandoned, but the next year Erwin S. Wolfson, head of the Diesel Construction Company, proposed a smaller tower on the present site of the Pan Am Building, north of the terminal's main concourse. His proposal was made to the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad, which had an interest in the terminal and his plan was designed by Fellheimer & Wagner, successors to Reed & Stem, part of the terminal's original design team. The terminal's principal owner at the time, the New York Central, was experiencing serious financial difficulties and had created a major controversy when it planned to install a three-level bowling alley in the 55-foot-high waiting room of the terminal. This plan, too, was eventually abandoned, but in 1958, Emery Roth & Sons came forward with another design for Wolfson, a 50-story, 3-million sq. ft. tower with a helipad and parking for 2,000 cars. In "New York 1960, Architecture and Urbanism Between the Second World War and the Bicentennial," Robert A. M. Stern, Thomas Mellins and David Fishman, (The Monacelli Press, 1995), noted that Roth's plans also called for two 1,800-seat theaters and a 1,200-seat movie theater and an open-air restaurant on the seventh floor. These features were eventually deleted from the plan. The building, they continued, which was then called the Grand Central City Building, was to be clad in aluminum and glass and the "north-south tower rising from the base would not be significantly wider than that of the New York Central Building" and "would thus cause a minimal disruption of the vista up and down Park Avenue." "But Wolfson felt uncomfortable with the modesty of the Roth design. Convinced that such a prominent site demanded something more, Wolfson asked Richard Roth to suggest a few possible design collaborators. Roth suggested Walter Gropius, who in turn suggested Pietro Belluschi," the authors noted. In an interview in October, 2001, Richard Roth provided the following commentary: "Wolfson decided that he might need a 'name architect' in order to secure financing, which was all but non-existant. Since I had just graduated from architectural school I was asked to draw up a list of famous architects. Wolfson, besides being my father's closest friend, was my godfather. I drew up a list based on whom I wanted to meet. The first choice was Mies, who was my idol, second Corbu. They were followed by Wright, Gropius, Belluschi, Breuer, Goff et al. Erwin and my father decided that Mies, Corbu or Wright would be too difficult to work with. Grope and Pietro were both heads of architectural schools and Erwin and my father thought they would just be happy to get some money and disappear. Ha! Gropius took over and Pietro took a real back seat. I later worked with Pietro on five other projects and he told me of his uncomfortable relationship with Grope and because of Grope's position in the world of architecture, took a all but non-role." Mr. Roth also noted that Gropius lamented the quality of granite used in the public spaces but when asked about the use of pre-cast concrete, "his answer was that he liked it!" In 1959, the three architects came up with a revised plan of a larger building with an "elongated" octagonal plan and a very bold pre-cast concrete facade. Stern, Mellins and Fishman observed that the new design was based on "a well-known prototype, Le Corbusier's unrealized skyscraper for Algiers (1938-42)" and was "also related to Gio Ponti and Pier Luigi Nervi's technologically innovative, far more sveltely proportioned Pirelli Building, then under construction in Milan." While such comparisons have a slight validity as far as form elements, a strongly indented facade in the former and squeezed ends in the latter, they are quite a stretch. The Roth, Gropius, Belluschi design, which is what was built here, is a highly original plan that could hardly be described as derivative. Wolfson, Trager noted, got $25 million for the project from Jack "King" Cotton, an English investor, and Pan Am became the major tenant. When it was completed, the 2.4-million sq. ft. building became the world's largest office building in bulk, a title it would lose a few years later to 55 Water Street downtown. The building was not popular: Ada Louise Huxtable of The New York Times, for example, described it as a "colossal collection of minimums" and "gigantically second-rate." A few years after its erection, the Penn Central, owner of the air rights over the terminal incurred even more public wrath than the developer of the Pan Am Building, when it proposed another major office tower over the terminal's famous concourse. In a major preservationist controversy that went all the way to the U. S. Supreme Court, the Penn Central argued that the original developer and architects of the terminal had not only planned a major tower to rise over the concourse but had also put its foundations in the corner piers of the terminal. The original 30-story tower was similar in design to the New York Central tower to the north of the Pan Am Building, but had a broader and less ornate roof. Interestingly, the new proposed tower was designed by Marcel Breuer, the architect of the revered Whitney Museum of American Art on Madison Avenue and 75th Street and the leading practitioner of Brutalist architecture in the country. The city and the civic groups that brought suit against Penn Central and its plan were successful in getting the U.S. Supreme Court to uphold the city's right to review proposed changes to the exterior of the terminal, which had been designated an official city landmark and the court argued that the financially troubled Penn Central had not exhausted all of its economic opportunities in selling off the undeveloped air-rights over the terminal's properties.

The ruling actually did not rule out the possibility of a new tower, contrary to the jubilant proclamations of the city's leading preservationists and the air-rights controversy continued for many years and affected other nearby sites. The rules of the development game in New York were changing rapidly. The demolition of the former Penn Station in 1964 led to the creation the next year of the city's landmarks law and civic groups began to take lessons in media management from the civil rights movement and to assert much more influence on politicians who were initially tentative about pursuing landmark regulations because of serious concerns about legal challenges from the city's real estate owners and developers. As a skyscraper, the MetLife Building is actually a great achievement if one could ignore its vista blocking. By slightly bending backwards the outer thirds of its north and south facades, it lessens the tower's great bulk from many viewpoints and by indenting, with widely spaced colonnades, the two major "mechanical floors" that house much of the building's huge heating and air-conditioning equipment the architects effectively broke the monotony of such large facades in an inventive manner. The latter treatment was also enhanced by creating a dark band on the north and south facades beneath the flat roof that provided a better background for placing logos and was a Modernistic attempt to figuratively make a "cornice" statement. Part of the roof, of course, is given over to major HVAC equipment and the rest was given over in 1965 to a heliport for large helicopters to whisk travelers to and from the city's airports. New York Airways offered a seven minute flight to Kennedy Airport for $7 in helicopters that carried eight passengers. It was closed in 1968 because it was not profitable, but reopened February, 1977, only to close again three months later when the landing gear of a large, 30-passenger helicopter collapsed as passengers were about to board and one of its rotor blades broke off, killing four people on the heliport and a pedestrian on the steet and crashed over the roof, ending the controversial, but incredibly exciting service. (New Yorkers have never caught on the fact that all major skyscrapers in downtown Los Angeles are required by the city to have flat roofs, each marked with their own number, to facilitate helicopter landings for emergencies such as high-rise fires.) If the building's innovative form and helipad were unappreciated, its lack of fine detailing has not gone unnoticed. The merits of the tower's form were terribly compromised by the developer's cheapness in not installing high-grade walls in the lobby. Almost all of the large, polished granite panels in the public spaces were severely blotched and unattractive. To make matters worse, a major redesign and renovation of the lobby spaces in 1987, shown at the right, did not improve matters much. The Egyptian motif splashed around the lobby and building perimeter by designer Warner Platner were not only inappropriate and incongruous, but, more importantly, were almost universally perceived as ghastly and garish. Platner gained great fame for his superb crystalline treatment of WaterTower Place, a very important and major mixed-use project in Chicago. His enormous, gilded lunettes, presumably representing palm trees would actually greatly enliven the Temple of Dendur hall at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and hopefully they will end up there someday.

In early 2002, the lunettes and most of Platner's design was removed and the north entrance is now blandly modern. It would be wrong to assume, however, that the owners of this building were without any aesthetic sensibility. Richard Lippold's gilded wire sculpture in the Vanderbilt Avenue lobby, shown below, is wonderful (although authors Stern, Mellins and Fishman found it "disappointing," describing it as "decidedly earthbound and stagy") and a large red, black and white banded painting by Josef Albers over the escalator bank between the building and the terminal is rhythmically rich. (Escalators lead from the main lobby to the second floor where the office tower's elevator banks are located.) Gyorgy Kepes designed two large aluminum screens with concentric squares near the information desk.

A major private dining facility, the Sky Club, is on the 56th floor, which for a few years also had a public restaurant with impressive views. |

| Special thanks to Carter B. Horsley of the www.thecityreview.com | |