|

New York

Architecture Images- Midtown New York Public Library Top 25 NY Buildings |

|

architect |

Carrere & Hastings |

|

location |

Fifth Ave., bet. W40 and W42. |

|

date |

1911 |

|

style |

Beaux-Arts |

|

construction |

stone |

|

type |

Library |

|

|

|

|

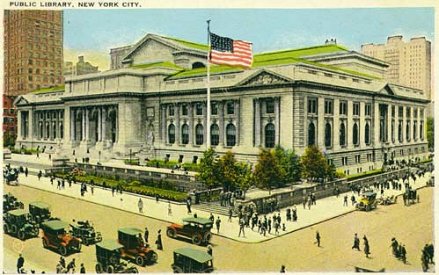

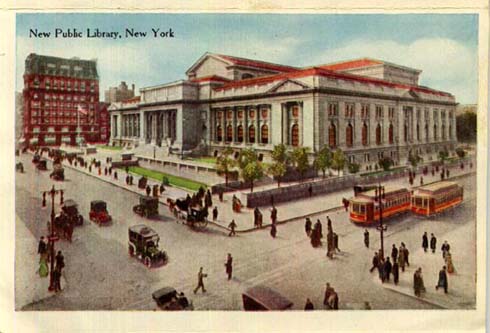

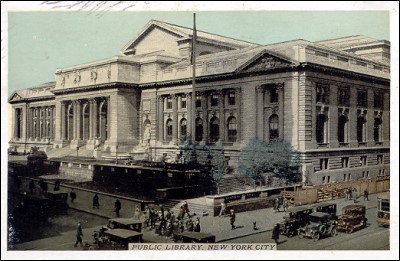

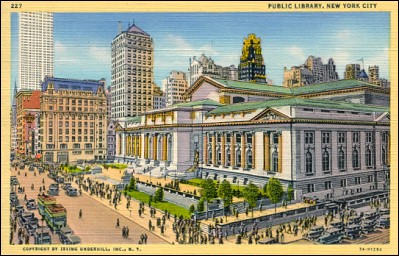

| Postcard, ca. 1920 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

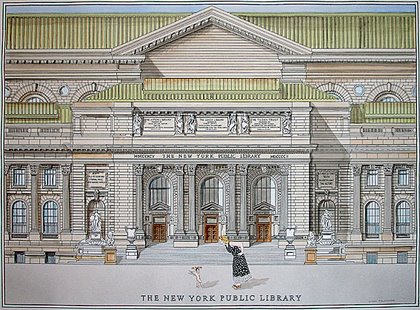

| Rendering copyright Simon Fieldhouse. Click here for a Simon Fieldhouse gallery. | |

|

|

| "Patience" and "Fortitude" : the "Library Lion" statues; New York Public Library with mantle of snow (record snowfall of Dec. 1948) | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

exterior images |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

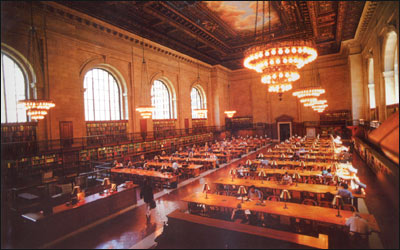

interior images |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

_small.jpg) _small.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

|

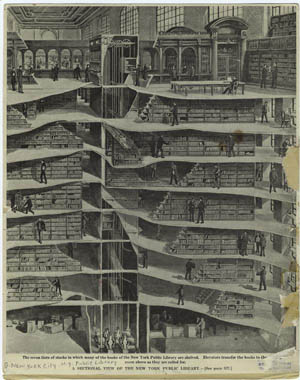

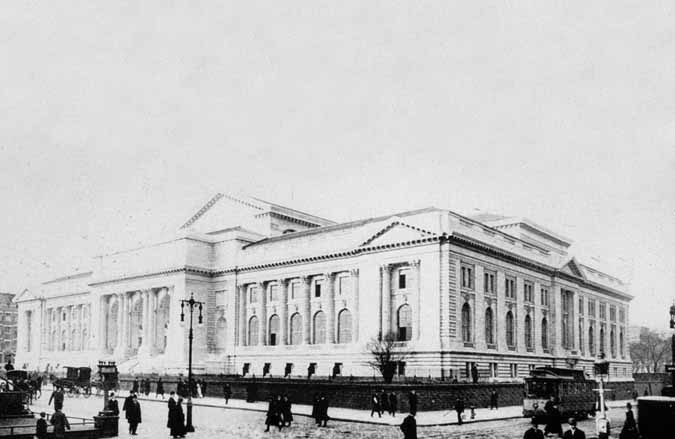

In his excellent and definitive book, "The New York Public Library Its Architecture and Decoration, published in 1986 by W. W. Norton & Company, Henry Hope Reed describes this correctly as "an edifice of stunning quality - a people's palace of triumphant glory." "Astor Hall, at the entrance," Reed continues, "with its unique stone vault above an awesome white marble interior, sets the tone for the architectural delights that lie in store for the visitor. Sumptuous light brackets, elaborately decorated ceilings, the great gallery extending along the north-south axis of the building on the first floor, the window bays, the doorways, the great stairways, all combine to lift the human spirit and dignify man's achievements. The elaborately decorated Main Reading Room, almost two city blocks in length, located at the top of the building for light and quiet, is a fitting climax to all that the architects wished to achieve." With McKim, Mead & White's demolished Pennsylvania Station and Warren & Wetmore's and Reed & Stem's Grand Central Terminal, the library is one of the most important Beaux-Arts structures ever erected in midtown. It has neither the incredible spaciousness drama of the former or the great location straddling Park Avenue of the latter, but it surpassed both in its consistently lavish decorative detail. The former Custom House at the foot of Broadway and the former Hall of Records building on Chambers Street, both downtown, are far greater Beaux Arts buildings, but much smaller, though still imposing. Compared with the sumptuous and extravagant interior decoration of the Library of Congress in Washington, of course, the New York Public Library actually is quite disappointing and relatively barren. But by New York standards, and more importantly, by New York pre-multimedia intellectual standards, it is hallowed grounds. Incredibly, this vital resource for research had been allowed to deteriorate and its very purpose denigrated for many years until the late 1980's when it began to be restored architecturally and serious attention given to its collections by means of a major expansion underneath Bryant Park behind it. But despite the publicity mavens who sit on its board and attend its black-tie fund-raising functions, its failure to keep its main reading room open 24 hours a day seven days a week every week of the year is outrageously contemptible and none of its officials and patrons have any right to respect until such a despicable situation is righted! There is, of course, much that is noble and fine about this institution and it is making an attempt to preserve its endangered collections and to utilize computer technology to assist its users, and certainly the task is formidable and the ultimate blame for it being less than perfect lies with the political leadership, namely, the mayors of the city who often seem more interested in pouring millions into ventures to enrich the owners of the New York Yankees than to educate the masses or the elite. As much as some critics want to believe that Manhattan's high-rise environment is what makes the city great, it is its cultural treasures and those include first and foremost the main library (not its branches) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Soapbox oratory aside, the symmetrical main Fifth Avenue facade of the library, a detail of which is shown at the right, is splendid, set back on a broad, landscaped terrace with exquisite flagpoles and fronted by its two famous lion statues, popularly known as Patience and Fortitude, that wear wreaths during the winter holidays. Edward Clark Potter was the sculptor of the benign lions. The facade has several important sculptures including Frederick MacMonnies' "Beauty," shown at the right, and George Grey Barnard's "Arts" and "History," on the south and north pediments, respectively. Atop the handsome portico are inscriptions about the library's three great benefactors: James Lenox (1800-1880) who built the Lenox Library on the present site of the Frick Collection on Fifth Avenue at 70th Street; Samuel Jones Tilden (1814-1886) a former New York Governor and Democratic candidate for President whose home on Gramercy Park is now the National Arts Club and who left $5 million to found a free public Liberia; and John Jacob Astor (1763-1848), who commissioned Washington Irving to write the story of Astoria, his trading post in Oregon and who became the richest man in the country and founded his own library on Lafayette Place in 1852 that is now the New York Public Theater. In 1897, the state approved city plans to replace the famous reservoir that occupied the site of the present library and much of what is now Bryant Park with a library and that year Carrère & Hastings won a design competition for the new library and McKim, Mead & White came in third and Howard & Cauldwell came in second. The exterior white marble came from Vermont and two-thirds of it was rejected as not high enough quality. The marble walls are one foot thick and the basement of the structure has additional brick walls four feet thick. According to Reed, architect Thomas Hastings had urged that the library and the city buy the Fifth Avenue frontage across from the library to a depth of 91 feet, the distance the main building is set back from the avenue, in order to give it a more important, ceremonial setting. Seen from 41st Street and Madison or Park Avenue, the library is visually crunched by subsequent development and Hastings unfulfilled wish was too modest, sadly. The library opened May 23, 1911. The dimensions of the library are impressive. Astor Hall, the main lobby behind the portico, is about 76 by 47 feet with a vaulted ceiling more than 37 feet high. The sinuous vaulted and the arched windows soften the space, as shown on the previous page, and the abundance of white marble is reassuring. Of interest is the robust and unusual balustrades of the twin staircases at the north and south ends of the hall, especially their rounded terminals. Although it is impressive, the hall's lack of major decoration and color makes it rather lifeless. One wishes for some exuberant flamboyance of which the American Renaissance was capable, but the overriding theme at the library is sober and very Classical. Directly across from the main entrance is Gottesman Hall, shown at the left, a large exhibition space that has an attractive ceiling but some rather large obstacles in the shape of groups of huge marble columns. If one ascends to the third floor one finally encounters some old-fashioned grandeur in the large hall that is the vestibule for the Main Reading Room's catalogue room. This "Landing Hall," shown above, is quite ornate, with stucco, according to Reed, painted to look like rich woods, and murals on printing themes by Edward Lanning in large arched panels. The murals were painted as part of the Works Progress Administration Project between 1932 and 1942 and are colorful, but uninspired and Lanning is not a major artist. Across from the entrance to the catalogue room on this level, however, is another exhibition room full of portraits and the library's only truly important American painting, "Kindred Spirits," a large landscape by Asher B. Durand depicting William Cullen Bryant, the writer after whom the adjacent park is named, and Thomas Cole, the founder of the Hudson River School of American landscape painting talking in an idyllic Catskill clove. If painting is not well represented at the library, most of the other artistic crafts are and visitors should look carefully at ceilings, doorknobs, fountains and furniture and the like. The Main Reading Room is, of course, the crowning glory of the library, or should have been. It is divided into a north and south wing with a center divider for the staff to distribute books that come up in dumbwaiters from the miles of stacks below and the center divider fortunately does not extend to the ceiling. The north wing of the Main Reading Room has been cluttered with less than brilliantly designed modern technology, but, fortunately, the south wing, shown below, remains very close to the original: very, very large tables with shaded lamps for the public's reading pleasure. Ceiling murals had suffered badly over the decades and by the 1990's had become barely discernible. Fortunately, Fred Rose, one of the city's leading real estate developers and philanthropists, came to the rescue and his family donated the funds to restore this great and hallowed space. The room, which can accommodate 636 readers, became known officially in November, 1998, as the Deborah, Jonathan F. P. Samuel Priest and Adam Raphael Rose Main Reading Room in honor of the children of Sandra Priest Rose and Frederick Phineas Rose. In an excellent story that appeared in The New York Times, Nov. 5, 1998, Julie V. Iovine quoted Paul LeClerc, the library's president, as stating that the main reading room, which is about the size of a football field and has 18 chandeliers, "is the key symbolic space within a library that rivals the great European libraries...and its essence is the most pluralistic, democratic access imaginable. The only criterion one needs to get in is curiosity." The ceiling murals could not be restored but the $15 million restoration painted new clouds. The room's large, arched windows were clearned and the last traces of black-out paint from World War II removed. The library has many specialized departments with their own large rooms and varying degrees of access and it also has a relatively ornate Trustees Room that is not open to public. The quality of sculpture at the library is excellent as can be seen the photograph above of two female figures on the Fifth Avenue facade. The main building has two large courtyards and the northern one is occupied by the recently restored glass domed auditorium, a very gracious space. The rear facade of the library facing Bryant Park, which has been very nicely restored and improved, is a big disappointment as it is large and graceless. A new restaurant pavilion, shown above, opened in 1995 on the terrace overlooking the park's great lawn and it has enlivened this area and because it is freestanding has not detracted from the library building. Despite the vastness of the library building, it only has one men's room, on the third floor, but two ladies' rooms, one on the third floor and one on the ground floor at the attractive 42nd Street entrance. In the early 1990's, the library succumbed to commercialism and opened a small and attractive gift store between Astor Hall and the north end of the first floor. |

|

New York Public LibraryTechnically, this is just one of four research libraries--the Humanities & Social Science Library, to be specific--but this is the heart and soul of the NYPL. One of the world's greatest libraries, the NYPL was formed in 1895 by combing the Astor, Lenox and Tilden libraries. From 1902 to 1911, this Beaux Arts architectural masterpiece designed by Carrere & Hastings was constructed to house the collection. Authors who have used the library include Isaac Bashevis Singer, E.L. Doctorow, Somerset Maugham, Norman Mailer, John Updike, Tom Wolfe and Frank McCourt. The Xerox copier, the Polaroid camera and the atomic bomb were all researched here. Almost all the information in Ripley's Believe It or Not! came from here--as did much of Reader's Digest. This was previously the site of the Croton Distributing Reservoir, a massive tank holding water from the Croton River, completed in 1842. Walking along its monumental Egyptian walls was a popular recreation, recommended by Edgar Allan Poe; the base of the reservoir serves today as the library's foundation.

The pink marble lions outside the library are Patience and Fortitude--nicknamed thus Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia. |

|

|

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is one of the leading public libraries

of the world and is one of America's most significant research

libraries. It is unusual in that it is composed of a very large

circulating public library system combined with a very large non-lending

research library system. It is simultaneously one of the largest public

library systems in the United States and one of the largest research

library systems in the world. It is a privately managed, nonprofit

corporation with a public mission, operating with both private and

public financing. Its flagship building, on Fifth Ave. running from 40th

to 42nd Street in Manhattan, is a National Historic Landmark. The historian David McCullough has described the New York Public Library as one of the five most important libraries in America, the others being the Library of Congress, the Boston Public Library, and the university libraries of Harvard and Yale. Although it is called the "New York Public Library" the system does not cover all five boroughs of America's largest city, only Manhattan, The Bronx and Staten Island. New York City does not have a single public library system but three of them. The other two are the Brooklyn Public Library and the Queens Borough Public Library, serving the boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens, respectively. This came about because these three library systems predate the consolidation of New York City in 1898. Currently, the New York Public Library consists of 87 libraries: four non-lending research libraries, four main lending libraries, a library for the blind and physically handicapped, and 77 neighborhood branch libraries in the three boroughs served. All libraries in the NYPL system may be used free of charge by all visitors. As of 2005, the research collections contain 15,634,320 books. The Branch Libraries contain 4,404,750 volumes.[1] Together the book collections total more than 20 million, a number surpassed by only the Library of Congress and the British Library. If the three public library systems of New York City were considered as a single entity this unified library would have 208 branches and a collection of more than 30 million volumes, making it the largest public library in the world.[2] History Founding An early benefactor of the New York Public Library was New York governor and presidential candidate Samuel J. Tilden, who left the bulk of his fortune -- about $2.4 million -- to "establish and maintain a free library and reading room in the city of New York." At the time of Tilden's death in 1886, New York already had two important libraries: the Astor Library, and the Lenox Library.[3] The Astor Library was created by John Jacob Astor, an immigrant who became the wealthiest man in America. When he died in 1848, he left $400,000 in his will for the establishment of a library in New York City. The Astor Library opened the following year, 1849. Although it was not a circulating library, it was a major reference library for research.[3] New York's other main library was established by James Lenox and consisted mainly of his extensive collection of rare books (which included the first Gutenberg Bible to come to the New World), manuscripts, and Americana. The Lenox Library was intended primarily for bibliophiles and scholars. While it was free of charge, tickets of admission (such as those that are still required to gain access to the British Library) were still needed by potential users.[3] So although there were already two fine libraries in New York City in 1886 and both were open to the public, neither could be termed a truly public institution in the sense that Tilden seems to have envisioned. But Tilden's vision was soon to come into fruition not only because of the generous bequest he left in his will but because of a man who was a trustee of his estate.[3] By 1892, both the Astor and Lenox libraries were experiencing financial difficulties. Almost as if fate would have it, John Bigelow, a New York attorney, and Tilden trustee, formulated a plan to combine the resources of the financially-strapped Astor and Lenox libraries with the Tilden bequest to form "The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations". Bigelow's plan, signed and agreed upon on May 23, 1895, was hailed as an example of private philanthropy for the public good.[3] The newly established library consolidated with The New York Free Circulating Library in February, 1901, and the philanthropist Andrew Carnegie donated $5.2 million to construct branch libraries, with the requirement that they be maintained by the City of New York. Later in 1901 the New York Public Library signed a contract with the City of New York to operate 39 branch libraries in the Bronx, Manhattan, and Staten Island.[3] Unlike most other great libraries, such as the Library of Congress, the New York Public Library was not created by government statute. From the earliest days of the New York Public Library, a tradition of partnership of city government with private philanthropy began. A tradition which continues to this day.[3] Main branch building The organizers of the New York Public Library, wanting an imposing main branch, found a prominent, central site available at the two-block section of Fifth avenue between 40th and 42nd streets, then occupied by the no-longer-needed Croton Reservoir. Dr. John Shaw Billings the first director of the library, created an initial design which became the basis of the new building (now known as the Humanities and Social Science Library) on Fifth Avenue. Billings's plan called for a huge reading room on top of seven floors of bookstacks combined with system designed to get books into the hands of library users as fast as possible. Following a competition among the city's most prominent architects, the relatively unknown firm of Carrère and Hastings was selected to design and construct the building. The result, a Beaux-Arts design, was the largest marble structure up to that time in the United States.[3] The cornerstone was laid in May 1902, but work progressed slowly on the project, which eventually cost $9 million. In 1910, 75 miles of shelves were installed, and it took a year to move and install the books that were in the Astor and Lenox libraries.[3] On May 23, 1911, the main branch of the New York Public Library was officially opened in a ceremony presided over by President William Howard Taft. The following day, the public was invited. Tens of thousands thronged to the Library's "jewel in the crown." The opening day collection consisted of more than 1,000,000 volumes. The New York Public Library instantly became one of the nation's largest libraries and a vital part of the intellectual life of America. Library records for that day show that one of the very first items called for was N. I. Grot's Nravstvennye idealy nashego vremeni ("Ethical Ideas of Our Time") a study of Friedrich Nietzsche and Leo Tolstoy. The reader filed his slip at 9:08 a.m. and received his book just six minutes later.[3] Two famous stone lions guarding the entrance were sculpted by Edward Clark Potter. They were originally named Leo Astor and Leo Lenox, in honor of the library's founders. These names were transformed into Lord Astor and Lady Lenox (although both lions are male). In the 1930s they were nicknamed "Patience" and "Fortitude" by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia. He chose these names because he felt that the citizens of New York would need to possess these qualities to see themselves through the Great Depression. Patience is on the south side (the left as one faces the main entrance) and Fortitude on the north.[3] The main reading room of the Research Library (Room 315) — a majestic 78 feet (23.8 m) wide by 297 feet (90.5 m) long, with 52 feet (15.8 m) high ceilings — lined with thousands of reference books on open shelves along the floor level and along the balcony; lit by massive windows and grand chandeliers; furnished with sturdy wood tables, comfortable chairs, and brass lamps. Today it is also equipped with computers with access to library collections and the Internet and docking facilities for laptops. Readers study books brought to them from the library's closed stacks. There are special rooms for notable authors and scholars, many of whom have done important research and writing at the Library. But the Library has always been about more than scholars, during the Great Depression, many ordinary people, out of work, used the Library to improve their lot in life (as they still do).[3] The building was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1965.[4] Over the decades, the library system added branch libraries, and the research collection expanded until, by the 1970s, it was clear the collection eventually would outgrow the existing structure. In the 1980s the central research library added more than 125,000 square feet (12,000 m²) of space and literally miles of bookshelf space to its already vast storage capacity to make room for future acquisitions. This expansion required a major construction project in which Bryant Park, directly west of the library, was closed to the public and excavated. The new library facilities were built below ground level and the park was restored above it. On July 17, 2007, the building was briefly evacuated and the surounding area was cordoned off by New York police because of a suspicious package found across the street. It turned out to be a bag of old clothes.[5] In the three decades before 2007, the building's interior was gradually renovated.[6] On December 20, 2007, the library announced it will undertake a three-year, $50 million renovation of the building exterior, which has suffered damage from weathering and pollution. All of the work was scheduled to be completed by the centennial in 2011.[7] Other research branches Even though the central research library on 42nd Street had greatly expanded its capacity, in the 1990s the decision was made to remove that portion of the research collection devoted to science, technology, and business to a new location. The new location was the abandoned B. Altman department store on 34th Street. In 1995, the 100th anniversary of the founding of the library, the $100 million Science, Industry and Business Library(SIBL), designed by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates of Manhattan, finally opened to the public. Upon the creation of the SIBL, the central research library on 42nd Street was renamed the Humanities and Social Sciences Library. Today there are four research libraries that comprise the NYPL's outstanding research library system which hold approximately 43,000,000 items. Total item holdings, including the collections of the Branch Libraries, are 50.6 million. The Humanities and Social Sciences Library on 42nd Street is still the heart of the NYPL's research library system but the Science, Industry and Business Library, with approximately 2 million volumes and 60,000 periodicals, is quickly gaining greater prominence in the NYPL's research library system because of its up-to-date electronic resources available to the general public. The SIBL, the nation's largest public library devoted solely to science and business, provides users with broad access to science, technology, and business information via 150 networked computer work stations. The NYPL's two other research libraries are the Schomburg Center for Black Research and Culture, located at 135th Street and Lenox Avenue in Harlem and the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, located at Lincoln Center. In addition to their reference collections, the Library for the Performing Arts and the SIBL also have circulating components that are administered by the NYPL's Branch Libraries system. Branch Libraries The New York Public Library system maintains its commitment to being a public lending library through its branch libraries in The Bronx, Manhattan and Staten Island, including the Mid-Manhattan Library, The Donnell Library Center, The Andrew Heiskell Braille and Talking Book Library, the circulating collections of the Science, Industry and Business Library, and the circulating collections of the Library for the Performing Arts. These circulating libraries offer a wide range of collections, programs, and services, including the renowned Picture Collection at Mid-Manhattan Library and the Media Center at Donnell. Of its 82 branch libraries, 35 are in Manhattan, 34 are in the Bronx, and 11 are in Staten Island. Telephone Reference Service The New York Public library has a telephone-reference system that was organized as a separate library unit in 1968 and remains one of the largest. Located in the Mid-Manhattan Library branch at 455 Fifth Avenue, the unit has 10 researchers with degrees ranging from elementary education, chemistry, mechanical engineering and criminal justice, to a Ph.D. in English literature. They can consult with as many as 50 other researchers in the library system. Under their rules, each inquiry must be answered in under five minutes, meaning the caller gets an answer or somewhere to go for an answer — like a specialty library, trade group or Web site. Researchers cannot call questioners back. Although the majority of calls are in English, the staff can get by in Chinese, Spanish, German and some Yiddish. Specialty libraries, like the Slavic and Baltic division, can lend a hand with, for example, Albanian. Internet inquiries make up only a third of the questions, but they can take up to 35 minutes each and 85% of total staff time. Internet inquiries come by e-mail (13,398 in 2005) and a one-on-one chat that resembles instant messaging (7,220 in 2005). While telephone calls have declined recently to fewer than 150 a day from more than 1,000, they still made up two-thirds, or 41,715, of all inquiries in 2005; the rest were by computer. Every day, except Sundays and holidays, between 9 a.m. and 6 p.m. Eastern Standard Time, anyone, of any age, from anywhere in the world can telephone 212-340-0849 and ask a question. The library staff will not answer crossword or contest questions, do children's homework, or answer philosophical speculations.[8]. The business reference desk number is 212-592-7000, ext 3. Website The New York Public Library website provides access to the library's catalogs, online collections and subscription databases, and has information about the library's free events, exhibitions, computer classes and English as a Second Language classes. The two online catalogs, LEO (which searches the circulating collections) and CATNYP (which searches the research collections) allow users to search the library's holdings of books, journals and other materials. The NYPL gives cardholders free access from home to thousands of current and historical magazines, newspapers, journals and reference books in subscription databases, including EBSCOhost, which contains full text of major magazines; full text of the New York Times (1995-present), Gale's Ready Reference Shelf which includes the Encyclopedia of Associations and periodical indexes, Books in Print; and Ulrich's Periodicals Directory. The NYPL Digital Gallery is a database of half a million images digitized from the library's collections. The Digital Gallery was named one of Time Magazine's 50 Coolest Websites of 2005 and Best Research Site of 2006 by an international panel of museum professionals. Other databases available only from within the library include Nature, IEEE and Wiley science journals, Wall Street Journal archives, and Factiva. The NYPL in popular culture Film The NYPL has frequently appeared in feature films. It serves as the backdrop for a central plot development in the 2002 film Spider-Man and a major location in the 2004 apocalyptic science fiction film The Day After Tomorrow. It is also featured prominently in the 1984 film Ghostbusters—a librarian in the basement reports seeing a ghost, which becomes violent when approached. In the 1978 film, The Wiz, Dorothy and Toto stumble across the Library and one of the Library Lions comes alive and joins them on their journey out of Oz. Other films in which the library appears include 42nd Street (1933), Portrait of Jennie (1948), Breakfast at Tiffany's (1961), You're a Big Boy Now (1966), Chapter Two (1979), Escape from New York (1981), Regarding Henry (1991), The Thomas Crown Affair (1999), and The Time Machine (2002). Television The NYPL was featured in the pilot episode of ABC's hit series Traveler, as the Drexler Museum Of Art, most often as backdrop or a brief meeting place for characters. In the episode "The Day the Earth Stood Stupid" in the animated television series Futurama, the giant brain is confronted by Fry in the library. In an episode of Seinfeld, Cosmo Kramer (Michael Richards) dates an NYPL librarian, Jerry Seinfeld is accosted by a library cop (Philip Baker Hall) for late fees, and George Costanza (Jason Alexander) encounters his high school gym teacher living homeless on the building's stairs who in fact has the book that Jerry never returned so he could get revenge on him and Geroge for his being fired in high school for giving George a wedgie. The NYPL is the setting for much of '"The Persistence of Memory," the eleventh part of Carl Sagan's Cosmos TV series. Novels Lynne Sharon Schwartz's The Writing on the Wall (2005), features a language researcher at NYPL who grapples with her past following the September 11, 2001 attacks. Cynthia Ozick's 2004 novel Heir to the Glimmering World, set just prior to World War II, involves a refugee-scholar from Hitler's Germany researching the Karaite Jews at NYPL. In the 1996 novel Contest by Matthew Reilly the NYPL is the setting for an intergalactic gladiatorial fight that results in the building's total destruction. In 1985, novelist Jerome Badanes based his novel The Final Opus of Leon Solomon on the real-life tragedy of an impoverished scholar who stole books from the Jewish Division, only to be caught and commit suicide. In the 1984 murder mystery by Jane Smiley, Duplicate Keys, an NYPL librarian stumbles on two dead bodies, circa 1930. Allen Kurzweil's The Grand Complication is the story of an NYPL librarian whose research skills are put to work finding a missing museum object. Donna Hill, who was herself an NYPL librarian in the 1950s, set her 1965 novel Catch a Brass Canary at an NYPL branch library. Lawrence Blochman's 1942 mystery Death Walks in Marble Halls features a murder committed using a brass spindle from a catalog drawer. A charming, lightly fictionalized portrait of the Jewish Division's first chief, Abraham Solomon Freidus, is found in a chapter of Abraham Cahan's The Rise of David Levinsky (1917). Smaller mentions of the library can be found in: Henry Sydnor Harrison's V.V.'s Eyes (1913) P. G. Wodehouse's A Damsel in Distress (1919) Christopher Morley's short story "Owd Bob" in his humor book, Mince Pie (1919) James Baldwin’s Go Tell It On the Mountain (1953) Bernard Malamud’s short story "The German Refugee," (in his Complete Stories [1997]; originally published in the Saturday Evening Post in 1963) Stephen King's Firestarter (1980) B.J. Chute's The Good Woman (1986) Sarah Schulman's Girls, Visions and Everything (1986) Isaac Bashevis Singer's posthumous Shadows on the Hudson (1998) Poetry Both branches and the central building have been immortalized in numerous poems, including: Richard Eberhart’s “Reading Room, The New York Public Library” (in his Collected Poems, 1930-1986 [1988]) Arthur Guiterman’s “The Book Line; Rivington Street Branch, New York Public Library” (in his Ballads of Old New York [1920]) Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s “Library Scene, Manhattan” (in his How to Paint Sunlight [2001]) James Haug’s “Heat: a Composite” (in his The Stolen Car [1989]) Muriel Rukeyser’s “Nuns in the Wind” (in The Collected Poems of Muriel Rukeyser [2005]) Paul Blackburn’s “Graffiti” (in The Collected Poems of Paul Blackburn [1985]) E.B. White's "A Library Lion Speaks" and "Reading Room" (Poems and Sketches of E.B. White [1981]) James Turcotte’s poem series “The New York Public Library,” his moving meditation on his advancing AIDS, which appeared in the Minnesota Review (1993) Ted Mathys’ "Inventory Entering the New York Public Library" (Gulf Coast [2005]) Jennifer Nostrand’s "The New York Public Library" (Manhattan Poetry Review [1989]) Susan Thomas’ "New York Public Library" (the anthology American Diaspora [2001]) Aaron Zeitlin's poem about going to the library, included in his 2-volume Ale lider un poemes [Complete Lyrics and Poems] (1967 and 1970) Other Excerpts from several of the many memoirs and essays mentioning The New York Public Library are included in the anthology Reading Rooms (1991), including reminiscences by Alfred Kazin, Henry Miller, and Kate Simon. Other New York City library systems The New York Public Library, serving Manhattan, the Bronx, and Staten Island, is one of three separate and independent public library systems in New York City. The other two library systems are the Brooklyn Public Library and the Queens Borough Public Library. The three library systems combined operate a total of 208 library branches. According to the latest Mayor’s Management Report, New York City’s three public library systems had a total library circulation of 35 million broken down as follows: the NYPL and BPL (with 143 branches combined) had a circulation of 15 million, and the QBPL system had a circulation of 20 million through its 62 branch libraries. Altogether the three library systems also hosted 37 million visitors in 2006. Private libraries in New York City, some of which can be used by the public, are listed in Directory of Special Libraries and Information Centers (Gale) References ^ New York Public Library Fact Sheet, 2006. ^ Queen Library Facts, Brooklyn Public Library Welcome Page. ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l [1]Web page titled "History" at the New York Public Library Web site, accessed December 20, 2007 ^ Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; no text was provided for refs named nhlsum ^ New York Public Library being evacuated. Twitter (17 July, 2007). Retrieved on 2007-07-17. ^ Pogrebin, Robin, "A Centennial Face-Lift For a Beaux-Arts Gem: Restoration of Library Facade Begins With Visions of a Nightly Sectacle", article, The New York Times, page B1, December 20, 2007 ^ [2]Web page (news release?) titled "The New York Public Library Will Restore its Fifth Avenue Building's Historic Facade / Project to be Completed in Time for Building's 2011 Centennial / (New York City, December 20, 2007)" at the New York Public Library Web site, accessed December 20, 2007 ^ "Library Phone Answerers Survive the Internet." The New York Times 19 June 2006.[3] The NYPL website contains much of the information used in this article. |

|