|

New York

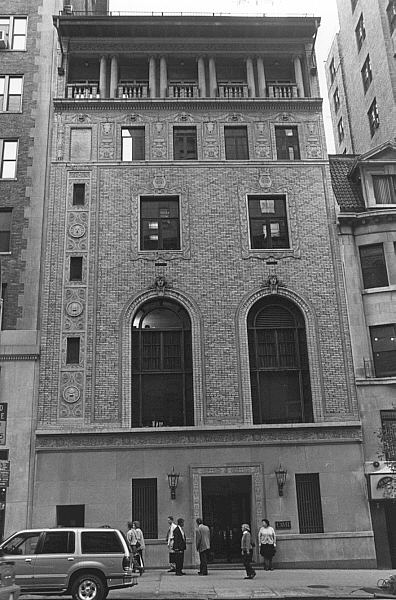

Architecture Images- Midtown LOUIS H. CHALIF NORMAL SCHOOL OF DANCING (now Columbia Artists Management Inc. (CAMI) Building) Landmark |

|

architect |

G[eorge]. A. & H[enry]. Boehm |

|

location |

165 W57, bet. Sixth and Seventh Aves. |

|

date |

1916 |

|

style |

Renaissance Revival |

|

construction |

Federal Terra Cotta Co., terra cotta |

|

type |

Education |

|

|

|

|

images |

|

|

|

|

|

The Louis H. Chalif Normal

School of Dancing was built in 1916 to the design of architects

G[eorge]. A. & H[enry]. Boehm. Louis Chalif (1876-1948), born in Odessa,

Russia, and trained in ballet there, immigrated to the United States in

1904 and established his school in 1905. Called "the dean of New York

dance teachers" and "the first Russian ballet master to teach in

America," Chalif was a major influence on the teaching of dance within

the American educational system. The Chalif School was one of the

earliest schools in the U.S. to instruct teachers in dance. The Boehm

brothers' partnership lasted from about 1912 to 1927; George Boehm is

best known for the design of the Jewish Daily Forward Building (1912), a

designated New York City Landmark. The sophisticated asymmetrical facade

of the five-story Chalif Normal School of Dancing, with motifs inspired

by the Italian Renaissance and Mannerism, features upper stories clad in

tan-gray colored brick, laid in a diamond pattern, and notable

polychrome terra cotta (manufactured by the Federal Terra Cotta Co.)

with classical and theatrical references. It is terminated by a

colonnaded loggia with a deep, overhanging copper cornice. The Chalif

School moved out of this building in 1933. The structure was later owned

from 1946 to 1959 by Carl Fischer, Inc., one of the most important

American music publishers, which operated a retail outlet here, as well

as the Carl Fischer Concert Hall. Columbia Artists Management Inc.

(CAMI) acquired the building in 1959 for its headquarters and a recital

hall. One of the world's largest and most influential management and

booking firms specializing in classical music, opera, theater, and

dance, CAMI was organized in 1930 as the Columbia Concerts Corp. through

the merger of a number of leading independent concert bureaus. For most

of its history, the Chalif School building has housed organizations

associated with the performing arts and has thus contributed to West

57th Street as a cultural center.

Special thanks to www.nyc.gov |

|

|

Streetscapes/165 West 57th Street; A

School for Dance Built by a Russian Immigrant By CHRISTOPHER GRAY Published: August 11, 2002, Sunday THE Russian immigrant Louis Chalif, who built a dance school in 1916 at 165 West 57th Street, once said that dance in the United States was often just ''a cannibalistic orgy.'' Chalif held on to his building for less than a generation, but he retained his outspoken views. The building has remained part of the world of performance, and its current owner, Columbia Artists Management Inc., has negotiated a deal that involves its air rights and the possibility of additional space in a new adjacent building. Chalif (pronounced ''sha-LEAF'') left his career as a professional dancer in Russia and came to the United States in 1904, when he was in his late 20's. He soon started teaching. In 1909, he was hired to instruct several thousand children in folk dances of all nations for a public festival. In a 1915 advertisement, Chalif described himself as a graduate of the ''Russian imperial ballet school'' and offered instruction in ''interpretative, aesthetic, racial, ballroom dancing.'' Another ad offered instruction in the fox trot, la Russe, the Brazilian polka and, recently invented by Chalif, the Indian Trot. In that year Chalif began a new building for use as his residence and his dancing school. On 57th between Sixth and Seventh Avenues, the new Chalif Normal School of Dancing was in the thick of the new arts district and just across from Carnegie Hall. Designed by George and Henry Boehm, Chalif's buff brick and polychrome terra cotta building was in the ''purely modern style,'' according to The Real Estate Record and Guide. Above the soft white marble ground floor rose a tapestry brick facade festooned with low-relief terra cotta, two double-height windows on the second floor -- lighting the ballroom -- and an open loggia at the fifth, or top, floor. Chalif and his family lived on the fourth floor, in a nine-room apartment, underneath a top-floor rehearsal space with large glazed areas and doors opened during warm weather. Chalif rejected the usual grand stairway in favor of two elevators -- far less imposing, but much more efficient. He organized or led several dance associations, aimed at both professionalizing dance instruction and regularizing the bewildering variety of steps. In 1922, according to The New York Times, he supported legislation, never approved, to regulate dance steps, to eliminate the shimmy, the toddle and ''other immodest dances.'' In 1924 he told The Times: ''As long as orchestras syncopate like barbarians banging on human skulls in a cannibalistic orgy, shoulders and arms will wriggle and writhe. Given a dignified tango or waltz rhythm, the body responds gracefully and with modesty.'' Chalif published at least five textbooks on dancing. The 1930 census recorded Chalif, 53, in the house with his wife, Sarah, 51, daughter, Frances, 19, and son, Amos, 11. Amos Chalif, who now lives in Morristown, N.J., recalls that ''it was a wonderful place to grow up -- I learned to ride a two-wheeler inside the building, with my older brother, Selmer, running up and down next to me.'' The elder Chalif lost the building in foreclosure in 1934, during the Depression. He moved out but retained his outspoken opinions. An unidentified 1930's clipping at the Lincoln Center Library for the Performing Arts reports that Chalif vigorously opposed the new fad of tap dancing. ''This is the age of Mussolini and Hitler,'' Chalif was quoted as saying. ''The whole world is full of hate, and so is the modernistic dance.'' When he died in 1948, Dance magazine called him the ''dean of New York dance teachers.'' The Chalif children kept the school open until 1955, and then continued to teach elsewhere. FROM 1946 to 1959 the old Chalif building was the headquarters of the music publisher Carl Fischer; it was then bought by Columbia Artists Management Inc., known as CAMI, a management and booking company that specializes in classical music, opera and dance. CAMI had the architect William Lescaze redo the first-floor facade in a severe modern style, but in 1983 it had the architects Marlo & De Chiara restore the original design, although in a simpler form and in limestone instead of marble. CAMI supported landmark designation for the building, which came in 1999, and now it has sold the air rights -- and a small building at 161 West 57th -- to a developer who plans to demolish the small structure and a larger building to the east. Deborah Keith, a spokeswoman for CAMI, said that the company had received money from the developer, Intell Management and Investment, for the air rights, but she would not disclose the amount. She said CAMI also has an option from the developer for two floors in a new building planned for the site. Gary Barnett, the president of Intell, said that preliminary plans called for a hotel with luxury condominiums on the top, but he said he could not provide more specifics. Inside the Chalif building only a portion of the ballroom is left to recall the structure's days as a school. In the rear section of the second floor, the original arched ceiling remains, with turquoise and yellow painted plaster and delicate plasterwork, including the figure of the Greek muse of dance, Terpsichore, anointing a young dancer. Ms. Keith said that the room, known as CAMI Hall, which seats 168, is used for open auditions for singers and accompanists. Amos Chalif said that his father often revisited the building, and that he does too. He teaches at the Barn Studio in Bernardsville, N.J. ''If I teach two more years,'' he said, ''the Chalifs will have been teaching dance in America for 100 years.'' Published: 08 - 11 - 2002 , Late Edition - Final , Section 11 , Column 1 , Page 7 Copyright New York Times. |

|