|

The New York

Athletic Club was founded in 1868 by Henry Buermeyer, John Babcock and

William Curtis. All were accomplished athletes with a singular

commitment to the growth and development of amateur sport in the United

States. Furthermore, they possessed the foresight to realize that the

time was right to introduce some organization - and uniformity of

measurement - into sporting endeavors across the country, if not around

the world. So, on September 8th of that year, Buermeyer, Curtis and

Babcock, with 11 other similarly inclined sportsmen, gathered in a

Manhattan tavern known as the Knickerbocker Cottage for the first

meeting of what would become the NYAC. Though all were men of vision,

none could have foreseen the impact their club would have on the world

of amateur and Olympic sport.

-It is impossible to detail the entire accomplishments - both sporting and

commercial - of the New York Athletic Club and its members. Suffice it

to say that the Club holds a unique place in the sporting pantheon, a

position it bolsters with each passing year.

-Thirty five NYAC athletes competed at the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney,

Australia. These athletes continued a tradition that began over 130

years ago, a tradition illustrating all that can be accomplished by

individuals of ability, vision and commitment, individuals who comprise

the cornerstone of the New York Athletic Club.

-Prior to the 2000 Games, NYAC members had won 115 Olympic gold medals, 40

silver medals and 47 bronze medals, more than all but four nations.

-NYAC members have included some of the most celebrated names from the

sporting world and beyond, George M. Cohan, Robert Ripley and Al Oerter

among them.

-The sport of competitive fencing was introduced to the United States by

members of the NYAC.

-The first squash courts in the USA were built at the NYAC and opened in

1903.

-The NYAC staged the first indoor track meet in the USA and the first ever

USA outdoor track and field championships in the United States.

-The NYAC built the USA's first running track constructed of cinders, at

the time an innovative, super-fast surface.

-The NYAC introduced the first "velocipede" or bicycle race to America in

1868.

|

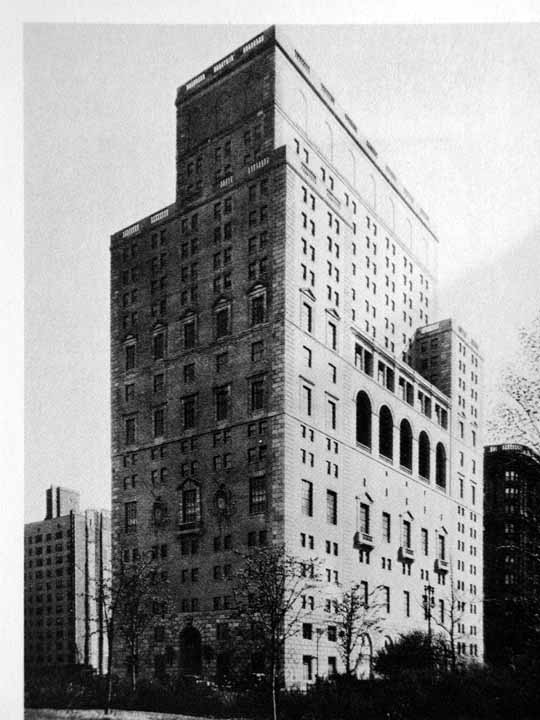

"The athletic facilities were gather together in the building's lower

floors, so that the ninth floor was the principal social floor with a

lounge and library. The private dining rooms were on the tenth floor,

and the grand...dining rooms seating 500 persons in all were on the

eleventh floor, where a large loggia was provided for summertime dining.

The location of the open-air loggia on the west side of the building

facing Seventh Avenue was unexpected, given the opportunity to face

Central Park across Fifty-ninth Street, but the greater extent of

Seventh Avenue frontage permitted a larger outdoor space. while the

detailin gof the limestone-clad Renaissance facades was not particularly

elaborate, the building was well massed, culminating in a stubby tower

in which two open and two closed handball courts wee located around a

42-by-62-foot solarium lit through quartz glass windows that opened to

all compass points."

Robert A. M. Stern, Gregory Gilmartin and Thomas Mellins, "New York 1930,

Architecture and Urbanism Between the Two World Wars," Rizzoli

International Publications, Inc., 1987.

Elizabeth Hawes, "New York, New York, How The

Apartment House Transformed The Life of The City (1869-1930)," An Owl

Book, Henry Holt and Company, New York 1993," provides the following

commentary about the "Spanish Flats, designed by Hubert, Pirsson &

Company, which had previously occupied the site.

"The same year the Chelsea opened [1883], the half-completed Central Park

Apartments was already being proclaimed the most elegant apartment house

in New York, the largest apartment house in the world, and the most

important building project ever undertaken, in terms of its novelty,

magnitude and cost. Designed by Hubert and Pirsson but also called the

Navarro, or Spanish Flats, in reference to its building, José F. de

Navarro, it occupied a half-block between Sixth and Seventh Avenues,

from 58th to 59th Street. It stood eight stories tall, towers, gables,

and turrets notwithstanding, and rising above the trees of the park, it

looked like a fortress, or a whole Moorish kingdom. The Navarro was a

single mass divided into eight separate apartment houses, which were

arranged around a central courtyard and connected internally only on the

first floor. Each house had a separate name and address - Navarro named

them the Barcelona, the Salamanca, the Cordova, the Tolosa, the Grenada,

the Valencia, the Madrid, and the Lisbon, after his favorite places -

and each was distinguishable by an entrance of triple arches. Inside,

each held twelve apartments of extraordinary dimensions. The largest

provided a drawing room (23 by 29 feet), a reception room (14 by 29),

dining room (20 by 23), kitchen (18 by 20) with several roomy pantries,

six bedrooms ranging from 22 by 24 to 14 by 18, three baths with tubs,

and three rooms for servants. It was munificent space, distinctly more

generous than an entire three-story house. There were not ten houses in

New York with such facilities for entertainments or occasions or

ceremony, where public rooms opened onto one another, like the French

nobleman's enfilade, and included a covered balcony that could be

converted into a formal conservatory when necessary. The general design

of the Navarro was even more impressive. Its suites were not only

lavishly decorated but also ingeniously arranged into simplexes,

duplexes, and triplexes (the first in the city), which were stacked up,

in an interlocking scheme similar to Hubert's mezzanine plan, to occupy

two stories in the front of the building and three in the rear. The

taller and grander rooms on the main floor were set before the park

vista, and the kitchen and bedrooms overlooked the interior courtyard,

where there was quiet and an abundance of light and air. The courtyard

of the Navarro was vast, 40 by 300 feet, a luxuriant space filled with

trees, flowers and fountains. To ensure the flow of resh air there, and

to harness the breezes that swept off the river and down across the

park, Hubert had also incorporated open archways into his bulding,

perforating its mass every second story between each of the eight

sections with passageway that was loggialike, and decorative, as well as

utilitarian. Beneath the courtyard another subterranean courtyard,

accessible by means of a vehicular tunnel leading directly from the

street, allowed carts and wagons to deliver their supplies and

provisions and to remove garbage and ashes in a manner that was

inaudible and invisible to tenants. It was the most original feture of

Hubert's technical design, which also included an apparatus to create

steam heat, a generator for electricity (electricity was as yet an

independent and expensive proposition in the city and therore a luxury

item in housing), and an artesia well to supply private water to the

building. Ironically the Navarro was ill fated as a cooperative. As

critics were extolling Hubert as an extraordinary architect of

apartments, famous for 'striking a mean between profusion and

parsimony,' the bank was foreclosing on his mortgage. It took over and

completed the project as a complex of rental buildings, for only half of

it was finished and functioning as a cooperative by 1885. Hubert's

'parsimony' was misplaced in this venture; his downfall wa a scheme by

which he had planned to lease the land, temporarily to the building

owners in order to limit their cash investments, an idea that was

untenable in the face of construction costs that ranked as high as those

for St. Patrick's Cathedral and the Plaza Hotel."

|