|

New York

Architecture Images- Midtown Hearst Magazine Building |

|

architect |

Joseph Urban, tower Sir Norman Foster |

|

location |

951-969 Eighth Ave at W47. |

|

date |

1928, tower 2004. |

|

style |

Art Moderne, tower Late Modern |

|

construction |

stone |

|

type |

Office Building |

|

|

|

|

images |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

|

| The atrium features escalators which run through a 3-story water sculpture titled Icefall, a wide waterfall built with thousands of glass panels, which cools and humidifies the lobby air. (photo wired ny) | |

.jpg) |

|

|

Hearst Tower in New York City, New York is located at 300 West 57th Street

on Eighth Avenue, near Columbus Circle. It is the world headquarters of

the Hearst Corporation, bringing together for the first time their

numerous publications and communications companies under one roof,

including Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping and the San Francisco

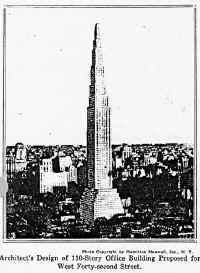

Chronicle, to name a few. The former six-story headquarters building was commissioned by the founder, William Randolph Hearst and awarded to the architect Joseph Urban. The building was completed in 1928 at a cost of $2 million and contained 40,000 sq. ft. The original cast stone facade has been preserved in the new design as a designated Landmark site. Originally built as the base for a proposed skyscraper, the construction of the tower was postponed due to the Great Depression. The new tower addition was completed nearly eighty years later, and 2000 Hearst employees moved in on 4 May 2006. The tower – designed by the architect Norman Foster and constructed by Turner construction – is 46 stories tall, standing 182 m (597 ft) with 80,000 m² (856,000 ft²) of office space. The uncommon triangular framing pattern (also known as a diagrid) required 9,500 metric tons (10,480 tons) of structural steel – reportedly about 20% less than a conventional steel frame. Hearst Tower was the first skyscraper to break ground in New York City after September 11, 2001. The building received the 2006 Emporis Skyscraper Award,[2] citing it as the best skyscraper in the world completed that year. Hearst Tower is the first green building completed in New York City, with a number of environmental considerations built into the plan. The floor of the atrium is paved with heat conductive limestone. Polyethylene tubing is embedded under the floor and filled with circulating water for cooling in the summer and heating in the winter. Rain collected on the roof is stored in a tank in the basement for use in the cooling system, to irrigate plants and for the water sculpture in the main lobby. The building was constructed using 80% recycled steel. Overall, the building has been designed to use 25% less energy than the minimum requirements for the city of New York, and earned a gold designation from the United States Green Building Council’s LEED certification program. The atrium features escalators which run through a 3-story water sculpture titled Icefall, a wide waterfall built with thousands of glass panels, which cools and humidifies the lobby air. The water element is complemented by a 70-foot (21.3 m) tall fresco painting entitled Riverlines by artist Richard Long. As reported on NPR's Wait Wait... Don't Tell Me!, women who wear miniskirts while riding the building's glass escalators offer those below a view up their skirts. |

|

|

Gross area: 856,000 ft2 / 79,500 m2 Zoning Area: 721,000 ft2 / 67,000 m2 (120,000 ft2 / 11,000 m2 from subway bonus) Typical Gross Floor area: 20,000 ft2 (1,900 m2) Typical Floor to Floor Height: 4 m Building Height: 597 ft (182 m) Number of storeys: 42 According to the numbers they already added in the bonus. "zoning bonus that would permit a building of 720,000 square feet, 20 percent larger than would usually be allowed" From September 2003 Issue of NY Construction News Showing Steel New Hearst Building to Use Innovative Steel Frame The Hearst Corp., which has long played a role in American society, will now impact the New York City skyline with a $500 million, 42-story steel and glass tower at Eighth Avenue and 57th Street. The Hearst story started in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when William Randolph Hearst’s newspaper empire brought into being the splashy daily tabloid in American journalism. The Hearst chain of newspapers, at one point read by one in four Americans, played a major role in stirring up support for the Spanish American War in 1898. Today, Hearst owns only 12 daily papers, but it has become the largest publisher of monthly magazines in the world. Among its better known titles are Cosmopolitan and Good Housekeeping, both of which it has published for nearly a century, and the more recent O, The Oprah Magazine. Hearst’s King Features Syndicate distributes some of the country’s most popular comic strips, including "Popeye," "Blondie" and "The Family Circus," along with advice columnists Dr. Joyce Brothers and Dr. Ruth Westheimer. Hearst owns 27 broadcast television stations that reach 17.5 percent of U.S. households, along with a number of popular cable networks including A&E, ESPN, Lifetime and the History Channel. Still on the Corner The new 856,000-sq.-ft. tower, when completed in 2006, will serve as the corporation’s world headquarters. The building at 959 Eighth Ave. has been designed by Lord Norman Foster of Foster and Partners in London, a Pritzker Prize-winning architect whose body of work includes renovation of the British Museum and the reconstruction of the Reichstag in Berlin. This is his first building in New York. Foster’s design preserves the six-story façade of the landmark Hearst-owned building that now stands on the corner. From its hollowed-out core will rise a geodesic-like office tower featuring triangular steel bracing from the 10th floor up. It will have no vertical columns around the perimeter, creating corner views that are not possible in a typically framed building. The steel framework will be a visible both inside the building and on the street. Referred to as the "diagrid" (a contraction of "diagonal grid") by those involved in the project, this perimeter will consist of 4-story-tall, grade-65 steel triangles prefabricated by the Cives Steel Co. at two plants, one in Gouverneur, N.Y., and the other in Winchester, Va. Cornell and Co. of Woodbury, N.J. will be the erector. "Our buildings are designed to show how they’re put together," said Mike Jelliffe, project director for Foster and Partners. "We use steel because it’s a lot more flexible. Concrete has its place; we have done many concrete buildings as well. But in the environment of New York, steel is the obvious choice." The Decision Building its new headquarters at the site of its original New York headquarters was also an obvious choice. Hearst, which currently has 1,800 employees spread out in nine separate buildings in Midtown, had long ago outgrown its real estate. "As leases were turning over we were reviewing several different options, which included renewing leases where we were, buying another property or developing one of several sites that we own, including 959 Eighth Ave.," said Brian Schwagerl, senior manager of facilities planning for Hearst. The Eighth Avenue site had several advantages, including its location on top of the Columbus Circle subway station, its proximity to Central Park just two blocks away, considerable air rights—and its history. The old building was designed specifically for Hearst in 1927 by Joseph Urban and George B. Post & Sons. The original plan had been to eventually add 12 more stories to the base building. On the roof of the old building you can still see the stub-outs of the columns that were designed to carry the additional load. The Depression intervened, and the additional stories were never built. In the meantime, the squat six-story building was designated a historic landmark. Four years ago Hearst asked Tishman Speyer Properties to do an analysis of the possibility of building on the site. "We did a feasibility study, put together design and approval teams and oversaw the approval process," said Bruce Phillips, senior director of design and construction for Tishman Speyer. Since the building had been landmarked, building on the site required approval from the Landmarks Commission, which allowed construction of the new building on the condition that the original façade be preserved. Because it is situated above the subway, the project also had to go through the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure. In the end, in exchange for improvements to the subway station—including a new entrance, installing three elevators, repositioning turnstiles and adding and moving stairwells—Hearst was given a bonus of six floors to add onto the tower. Phillips and his crew gave Hearst a list of possible architects. "Foster’s work on the Reichstag and the British Museum where he brought the old and new together attracted us," Schwagerl said. Tishman Speyer has stayed on as development manager and will oversee the project until completion. The Cantor Seinuk Group Inc. quickly joined the team as structural engineer and Flack and Kurtz Inc. as mechanical engineer. Turner Construction Corp. is the construction manager. The Diagrid The unusual design of the building’s exoskeleton has meant a close working relationship between Foster’s team and structural engineer Ahmad Rahimian, executive vice president at Cantor Seinuk. "Working with Cantor Seinuk, we developed this triangulated concept, this diagonal grid that breaks up the sides," Jelliffe said. "It’s a three-bay elevation to the east side and a four-bay elevation on the north and south sides. At the corners (because there are no vertical columns) we had the opportunity to create something special. "We cut back the diagrid to form what we term the ‘birds’ mouths.’ They open up most of the floors and allow a much more panoramic view. So when you’re standing on those floor plates you’re not looking into corners, you’re looking into chamfers which open up the view." Triangular bracing on the perimeter of a skyscraper is not new. It has been done before, most notably for the John Hancock Building in Chicago. "What’s unique about this is that there is no column, no vertical element on the perimeter; it’s all triangulated," said Rahimian. "The triangular frames carry the gravity load. At the same time, the triangulation has inherent strength and resistance to the lateral loads, seismic and wind. …The triangulated shape means you don’t need any additional bracing and you don’t need to have any concrete walls in the building." Because the triangles are so efficient in terms of bearing both the gravity and lateral loads, the building will use 21 percent less steel tonnage than a conventional building of its size. The diagrid also allows for larger open floor plates, which Hearst considers important. Schwagerl said some of the older buildings in the neighborhood are beautiful, but "inside they not very helpful to us as we put out our magazines. These 22,000-sq.-ft. floor plates are designed to give us the open space we want." The Old and the New The diagrid begins at the 10th floor. From 10 down the building rests on raking mega-columns that allow for vast open spaces for the lobby, a cafeteria, meeting rooms and other public spaces. "The tower loads are collected in a few locations with the mega-columns coming all the way down from the 10th floor to the foundation," Rahimian said. None of the structural elements of the old building will remain; the new building will have its own foundation and new columns. Only the framing at the perimeter of the old building will remain to stabilize the existing landmark façade, and even that is being upgraded to meet current wind and seismic criteria. "From the bottom to the 10th floor is one structure and from the 10th floor up, it’s framed entirely differently," said Ted Totten, president and general manager of Cives Steel Co. "Considerable steel work will be required to reinforce the historic façade. The mega-column/mega-brace system up to the 10th floor consists of 44-in. square plate box weldments. Then from the 10th floor to the 42nd, the building changes to an exposed exterior diagrid column system. The wide flange diagonal columns and 10-in. plate connection nodes will require special fabrication and erection skills to interface the steel frame with the curtain wall system.," he added. "We will be field assembling the diagrid system in 4-story A frames, with the intermediate beams preinstalled to the columns, which will then be set in one piece." "You enter through the existing arch (on Eighth Avenue) that is part of the landmark element and will be left well enough alone," said Jelliffe. "Then it opens up and you immediately see three escalators in front of you which take you up to the third floor level. Those escalators are set into a sloping water sculpture, which will cascade down past you as you’re going up." The third to the seventh floors will be an atrium divided into different areas for different uses and enclosed in a skylight. "When you’re sitting in the cafeteria, you can look up through the skylight and see the tower soaring above on one side and you can see the existing landmark wall on the other," Jelliffe said. Green and Secure In addition to its innovative architectural and structural features, the new Hearst Building is being constructed with an eye toward attaining LEED certification from the U.S. Green Building Council. "The efficiency of the steel frame of the building, which will resist wind and lateral forces with less tonnage, is an innovation worthy of note within the LEED system," Phillips said. "We’ve also developed some energy-efficient HVAC systems. For example, to heat and cool the giant atrium space we will be using spill air from the tower. That will allow us to provide most of the a.c. and heat from so-called waste air." In the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, Foster made some changes. The building’s core, rather than being in the center, has been positioned at the west side of the building away from any possible assaults from the street. (This offset core also allows for a larger footprint and more open space on the east side of the building.) In addition, concrete block will be used to contain the stairways, which will be wider than in most pre-Sept. 11-office buildings. Demolition of the old building began in May. The foundation work is scheduled to begin in October. Totten said the steel will start rising in February and should take about a year to complete. "We spent the last hundred years on this corner; we hope to spend the next hundred, and beyond, here," Schwagerl said. "We are creating a building that will support the company through the next century." DEVELOPMENT TEAM Owner/Developer: The Hearst Corp., New York Design Architect: Foster and Partners, London, U.K. Production Architect: Adamson Associates Architects, Mississauga, Ontario Development Manger: Tishman Speyer Properties, New York Construction Manager: Turner Construction Corp., New York Structural Engineer: The Cantor Seinuk Group Inc., New York Mechanical Engineer: Flack + Kurtz Inc., New York Steel Fabricator: Cives Steel Co., Gouverneur, N.Y. Steel Erector: Cornell and Co., Woodbury, N.J. December 21, 2003 COMMERCIAL PROPERTY | MIDTOWN A Tower Designed to Be Environmentally Friendly By JOHN HOLUSHA Brian Schwagerl, senior facilities manager, with a model of the Hearst Corporation headquarters building at Eighth Avenue and 56th Street. THE new Hearst Corporation headquarters building at Eighth Avenue and 56th Street will be an architectural standout, with a 42-story stainless steel and glass tower designed by Norman Foster rising from the interior of the six-story masonry structure the company has occupied since 1928. The building is also being designed and equipped to be energy efficient, to minimize waste and to provide a bright, attractive interior environment for the 1,800 employees who will work there. Such an approach is considered green, or environmentally friendly, because it reduces the consumption of resources while holding down pollution added to land, air and water. Indeed, executives of the privately held corporation, say they will be seeking the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design award from the United States Green Buildings Council, a nonprofit association of designers, builders and consultants pressing for environmentally thoughtful development. No building in New York City has ever won the award, although several upstate projects have been designated. Because Hearst will own and occupy the building, both the exterior and interior will be rated according to the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design criteria, more commonly known as the LEED standards. Another new Manhattan building, 7 World Trade Center, is expected to seek the LEED award under a different set of standards, the organization's new core and shell criteria, according to Ashok Gupta, an official of the Natural Resources Defense Council, a leading environmental group. This is because developers of multitenant buildings build only the inner core and outer shell of their structures, with the tenants controlling the layout and finishing work of their own spaces. The new criteria could allow Silverstein Properties, which is building the replacement for one of those destroyed in the Sept. 11 attack, to seek the award for its own efforts, regardless of tenant decisions. The Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design program is an important effort in the right direction, said Mr. Gupta, who is director of the Natural Resources Defense Council's air and energy program. "LEED is a good test; it's really the only one out there," he said. "It has become a national standard." But because it was designed with suburban projects in mind, with points awarded for installing bicycle racks and having grass growing on the roof, it has been difficult for skyscrapers in urban locations like Manhattan to qualify. "It is harder for urban buildings to score points," Mr. Gupta said. The approach at the Hearst tower appears to be a combination of common sense, careful attention to how office buildings actually operate, canny shopping and some innovative design. Whether it will meet the green building criteria cannot be determined until the 850,000-square-foot, $500 million tower is completed in June 2006. But with officials of both the developer, Tishman Speyer Properties, and one of its consulting engineers, Flack & Kurtz, on the board of the Green Buildings Council, it will not lack for advice. PART of the common sense part of the approach is to ban the use of materials, coatings and adhesives that emit volatile organic compounds — known as V.O.C.'s — a family of chemicals that may include some that are health hazards. "We won't have a new building smell," said Brian Schwagerl, senior facilities manager with Hearst. "We will have zero V.O.C.'s. Another is recycling, which reduces the amount of waste to be disposed of and reduces the amount of virgin materials that need to be grown or mined to develop new products. Although the new tower was developed conceptually as an extension of the tower originally designed to eventually be built on top of the old structure, in fact the existing building has been gutted to its landmarked walls. In recent weeks, excavation machines have been pounding at the hard Manhattan bedrock to prepare a foundation for the new building. According to Mr. Schwagerl, about 85 percent of the demolished material has been recycled in one way or another. The steel for the new structure will be 20 percent lighter than that in a typical Manhattan office building because of the structural design and will contain at least 90 percent recycled content. (Since virtually all the structural steel produced in the United States comes from mills that use scrap steel as a raw material, project managers would have been hard pressed to find beams and columns made from iron ore.) One of the distinctive features of the building will be a grand three-story atrium, with escalators taking visitors, who will come through the existing entrance on Eighth Avenue, upward under a skylight. The escalators will be set amid a stepped wall with water flowing downward as the people rise. Regulating the temperature of such a large space would normally require huge volumes of chilled air and big refrigeration units to produce it. Engineers working on the project have devised some other solutions. For one thing, all the glass in the building will have a coating that tends to admit visible light while reflecting a large part of the invisible solar radiation that causes heat. The floor of the atrium will be fitted with pipes that contain chilled liquid that will absorb the heat rays that do enter, before they can be reflected back into the air. "The entrance opens into a 70- to 80-foot-high space with a skylight," said Asif Syed, a senior vice president of Flack & Kurtz. "That volume of space would consume a lot of energy with conventional air-conditioning." Because of the tubes, which can carry heated or chilled fluid depending on the season, the floor becomes a radiant surface either emitting heat or absorbing it, without the need for conventional air-conditioning units and ductwork. This approach has been used in Europe to cool large spaces, Mr. Syed said, but as far as he knows, it is the first time it has been used in Manhattan. Even the water feature surrounding the escalators is being pressed into service to help control the temperature in the entry space. "The water feature is there for architectural reasons, but we can use it by chilling the water flowing over it," Mr. Syed said. "If we want an ambient temperature of 75 degrees, we will cool the water to 65 degrees so that the water feature becomes a radiant chilling source as well." In the upper floors of the building, high efficiency air-conditioning equipment will be used, with sensors and variable speed blowers designed to adjust the volumes of air according to actual need, rather than at a preset level. The chilling units will use none of the chemicals that have partially depleted the earth's protective ozone layer in the atmosphere. "We have a system that will respond to the needs of the building," Mr. Syed said. "At lunchtime, when people leave and are not running their computers and generating heat, the sensors will detect this and adjust the system." LIGHT and motion sensors are to be installed as well, to turn off lights when people are absent or when there is enough natural light coming the glass outer wall that artificial lighting is not needed. "In closed offices we will use a motion sensor, and in open spaces, a light sensor," he said. "There will be a great deal of natural light, but people just do not turn off their lights, even when they do not need them." A grass roof may not be practical in Manhattan, but the roof on the Hearst tower will be put to use to collect rainwater. This is expected to result in a 25 percent reduction in the amount of water that will be dumped into the city's sewage system during rainfalls, compared with a similar conventional building. The rainwater will be stored and used to replace water lost to evaporation in the office air-conditioning system. It will also be fed into a special pumping system to irrigate interior plantings and street trees. The captured rain is expected to account for about 50 percent of the tower's irrigation needs. Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company |

|

|

Facts and Figures Hearst Tower is the first building to receive a Gold LEED certified rating for "core and shell and interiors" in New York City. (The United States Green Building Council certified the Tower on September 22, 2006). The cost of foreign-sourced materials represents less than 10% of the cost of the construction of the Tower itself. The "diagrid" frame of the Tower will contain roughly 20% less steel than would a conventional perimeter frame — saving approximately 2,000 tons of steel. Each triangle in the diagrid is four stories tall, or 54 feet. Daylight sensors to control lighting and reduce energy use Over one mile of glass office fronts Over 90% of structural steel contains recycled material Fitness Center 15 passenger elevators 7 miles of storage filing space Wi-Fi enables 14,000 light fixtures Over 16,000 ceiling tiles State-of-the-art laboratory and test kitchens High-speed fiber optic data transmission — 10x faster than now Full-service television studio Dedicated video distribution network Gross Area: 856,000 ft² / 79,500 m² Zoning Area: 721,000 ft² / 67,000 m² (120,000 ft² / 11,000 m² from subway bonus) Typical Gross Floor Area: 20,000 ft² (1,900 m²) Typical Floor to Floor Height: 13’-6" (4 m) Building Height: 597 ft (182 m) Number of Stories: 46 Credits Client: Hearst Corporation Architect: Foster and Partners Associate Architect: Adamson Associates Structure: Cantor Seinuk Group MEP: Flack & Kurtz Vertical Transportation: VDA Lighting: George Sexton Food Service: Ira Beer Development Manager: Tishman Speyer Properties Subway Improvements Hearst Communication Inc. (Hearst) is complying with the American's With Disability Act (ADA) and making improvements over pedestrian traffic flow at Columbus Circle Station as part of their overall construction of the new headquarters project. Hearst commenced the improvements in January 2004 with final completion of all work scheduled for this Fall 2005 (better than the agreed upon 2-year schedule with New York City Transit). The Hearst improvements include: • 3 new ADA-compliant elevators (mezzanine to platform) • 2 new stairs (mezzanine to platform) • 4 reconfigured stairs - widened and reoriented (mezzanine to platform) • 2 refurbished stairs to street level through the new Hearst Building • Relocated fare stations for better accessibility and traffic flow These improvements, coupled with an existing elevator to street level, and other New York City Transit work, will provide better access to the station for persons with disabilities. Columbus Circle Station is the 14th busiest station (out of over 400) in the New York City Transit System. Green Facts Hearst Tower: A Pioneer in Environmental Sustainability In deciding to move forward in the fall of 2001 with ambitious plans to build a 46-story, Lord Norman Foster-designed, iconic headquarters tower above its historic six-story base, the leaders of Hearst Corporation made a bold commitment to its 2,000 employees and the City of New York. New York City's Columbus Circle neighborhood had been Hearst's home for 80 years, and with that momentous decision, Hearst dedicated its next eighty years to the area. This commitment by Hearst Corporation, however, is much more than merely a real estate decision. From design through construction, furnishing and occupancy, Hearst has committed itself to producing the most environmentally friendly or "green" office tower in New York City history. When the Hearst Tower is complete, it is expected to be the first office building in New York City to earn a Gold Rating under the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) by the U.S. Green Building Council, which is recognized as the nation's leading authority on environmentally sensitive design and construction. This is a significant achievement given that, prior to the Hearst Tower project, many doubted that a high-rise office tower in New York City could achieve official green status. Hearst is proving not only that it can be done but providing a successful road map to achievement. In doing so, Hearst is setting a higher standard for green building. For New York City, the benefits include significant reductions in pollution and increased conservation of the City's vital resources, including water and electricity. For Hearst employees and visitors, it means a healthier, more inviting and more productive working environment. For New York City's major corporations and building developers, Hearst has set a higher standard for building green. The environmentally conscious approach began prior to construction. When demolishing the interior portions of the existing, six-story structure, Hearst and its team of building professionals went to great lengths to collect and separate recyclable materials. As a result, about 85 percent of the original structure was recycled for future use. Working with Lord Foster, Hearst settled upon an innovative "diagrid" system (a word contraction of diagonal grid), that creates a series of four-story triangles on the façade. No verticle steel beams are being used, which is a first for North American office towers. In addition to giving the tower a bold architectural distinctiveness, it is providing Hearst with superior structural efficiency. As a result, Hearst eliminated the need for approximately 2,000 tons of steel, a 20 percent savings over a typical office building. Hearst executives also selected an innovative type of glass that wraps around the exterior of the building. The glass has a special "low-E" coating that allows for internal spaces to be flooded with natural light while keeping out the invisible solar radiation that causes heat. In conjunction with the glass, Hearst is installing light sensors that will control the amount of artificial light on each floor based on the amount of natural light available at any given time. The optimization of natural light has been demonstrated in recent studies to have important, positive effects on occupant health, quality of life and productivity. Hearst also will utilize technology that senses activity level. At lunchtime, when some employees are leaving or not using their computers, motion sensors will detect this and adjust the system accordingly. These sensors will allow for lights and computers to be turned off when a room is vacant. In addition, Hearst is using high efficiency heating and air-conditioning equipment that will utilize outside air for cooling and ventilation for 75 percent of the year, as well as Energy Star appliances. These and other energy-saving features are expected to increase energy efficiency by 22 percent compared to a standard office building. This is a welcome innovation in New York City, where rapidly growing electricity demand is threatening to overwhelm the local power supply. Hearst is also employing pioneering technologies in order to conserve and more efficiently use water. For example, Hearst's roof has been designed to collect rainwater, which will reduce the amount of water dumped into the City's sewer system during rainfall by 25 percent. The rainwater will then be harvested in one 14,000-gallon reclamation tank located in the basement of the Hearst Tower. The rainwater will be used to replace water lost to evaporation in the office air-conditioning system. It also will be fed into a special pumping system to irrigate plantings and trees inside and outside of the building. It is expected that the captured rain will produce about half of the watering needs. The harvested water also will be utilized for "Icefall," a three-story, sculpted water feature within the building's grand atrium. In addition to serving as a stunning entrance to the building, Icefall, which is believed to be the nation's largest sustainable water feature, will also serve an environmental function by serving to humidify and chill the atrium lobby as necessary. Hearst's focus on green does not stop after construction and installation of building systems. In fact, Hearst made a conscious choice at the outset of the tower project to make environmental considerations a major factor in every single decision, including the interior spaces. While the tower was designed to include as few internal walls as possible in order to maximize natural light, the walls that do exist will be coated with low vapor paints. Workstations and offices will be furnished with desks, chairs and other furniture that is formaldehyde free. Concrete surfaces will be furnished with low toxicity sealants. In a nod to ecological conservation, the floors beneath and the ceiling tiles above will be manufactured with recycled content. Hearst Corporation has long been an integral part of New York City and a vital contributor to the metropolis' unquenchable passion for boldness and innovation. With its emphasis on architectural distinction, modern technology and sustainable design, the Hearst headquarters tower becomes the very embodiment of Hearst's pioneering tradition. Trivia • George B. Post & Sons was the architect of William Randolph Hearst's rival Joseph Pulitzer's World Building as well as the original New York Times building. • Urban became art director of Hearst's new film making studio, remodeled the Criterion and Cosmopolitan theaters for him and designed the Hearst-financed Ziegfeld Theater while serving as a set designer for the Metropolitan Opera. • Urban collaborated with Benjamin Wistar Morris on the design of the Opera’s new house on 57th Street just three months after filing plans for the International Magazine Building. Each proposal included high-rise components and since Urban had little experience in that area, George B. Post Sons was brought on board. The Opera house was never built. |

|

| http://www.hearst.com/tower/ | |