|

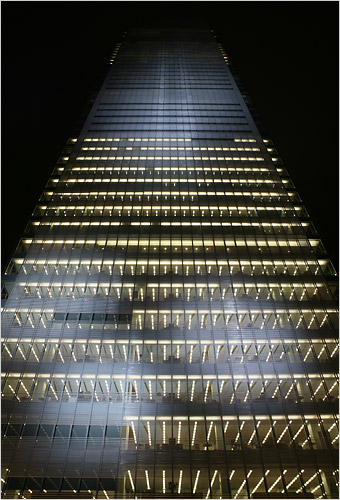

New York Architecture Images- Midtown The New York Times Building |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

architect |

Renzo Piano, Fox & Fowle Architects | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

location |

Eighth Avenue between Fortieth and Forty-first Streets. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

date |

2004 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

style |

Late Modern (International Style III)

“Mr. Piano’s building is rooted in a more comforting time: the era of corporate Modernism that reached its apogee in New York in the 1950s and 60s. If he has gently updated that ethos for the Internet age, the building is still more a paean to the past than to the future.” |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

construction |

The facades of the tower are a combination of

glass curtain walls and a ceramic tube screen. Daver Steels tie bars, M100

to M56 provide bracing to each corner of the building. Daver Steels secured this project by providing both an economic and practical solutions to the tensioning of this structure. In total Daver Steels supplied 280 tonnes of tie bars direct from the UK. All tie bars were supplied with a 2 coat paint system and shipped fully assembled. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

type |

Office Building | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

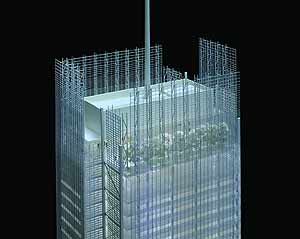

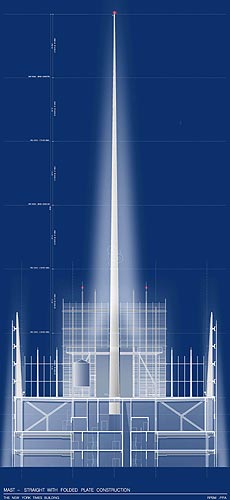

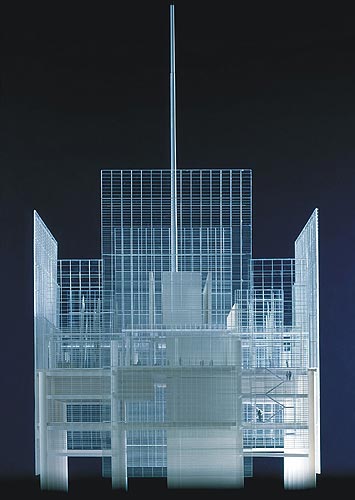

| The final built result doesn't quite look like the renderings.... | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Image credit: The New York Times Company / Forest City Ratner Companies / Renzo Piano Building Workshop / Fox & Fowle Architects |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The building under construction in September 2006. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Groundbreaking: Early 2003 Occupancy by The New York Times Company: Summer 2005 Tenant occupancy: Winter 2006 Government Team State of New York: The 42nd Street Development Project A subsidiary of the Empire State Development Corporation State Architectural Consultant: Robert A.M. Stern Architects Development Team: Architects: The Renzo Piano Building Workshop Fox & Fowle Architects, PC Structural Engineers: Thornton-Tomasetti Engineers Mechanical Engineers: Flack & Kurtz, Inc. Vertical Transportation Engineer: Jenkins & Huntington, Inc. Subsurface Investigation: Muesser Rutledge Consulting Engineers Landscape Architect: H.M. White Site Architects Lighting Designer: OVI (Office for Visual Interaction) Acoustical Consultant: Cerami & Associates Preconstruction Advisor: AMEC Corporation For The New York Times Company: Real Estate Advisors: Insignia/ESG Development Consultant: The Clarett Group Owner's Representative/Interiors: Gardiner & Theobald Interior Architect: Gensler Associates http://www.arcspace.com/architects/piano/NYT/index_a.htm |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

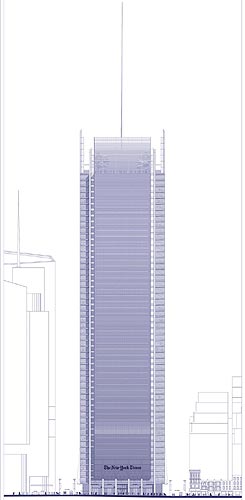

The New York Times Building is a skyscraper on the west side of Midtown

Manhattan that was completed in 2007. Its chief tenant is The New York

Times Company, publisher of the The New York Times, The Boston Globe,

the International Herald Tribune, as well as other regional papers.

Construction was a joint venture of The Times Company, Forest City

Ratner Companies - the Cleveland-based real estate firm constructing

redeveloping the Brooklyn Atlantic rail yards, and ING Real Estate. Background The project was announced on December 13, 2001, entailing the erection of a 52-story tower on the east side of Eighth Avenue between 40th and 41st Street across from the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey Bus Terminal. The project was announced shortly after the Hearst Corporation was given approval to construct a tower over their landmark six-story headquarters along the west side of Eighth Avenue, between 56th and 57th Streets. In conjunction with the Hearst Tower, the site selection represents the further westward expansion of Midtown along Eighth Avenue; a corridor that had seen no construction following the completion in 1989 of One Worldwide Plaza. In addition, the new location keeps the paper in the Times Square area, which was named after the paper following its move to 42nd Street in 1904. The Times Company had most recently been located at 229 West 43rd Street. The site for the building was obtained by the Empire State Development Corporation through eminent domain. With a mandate to acquire and redevelop blighted properties in Times Square, ten existing buildings were condemned by the EDC and purchased from owners who in some cases did not want to sell, asserting that the area was no longer blighted (thanks in part to the earlier efforts of the EDC). The EDC though prevailed in the courts. Once the 80,000 square-foot site was assembled, it was leased to the New York Times Company and Forest City Ratner for $85.6 million over 99 years (considerably below market value). Additionally, the New York Times Company received $26.1 million in tax breaks. Design The building under construction in September 2006.The tower was designed by Renzo Piano Building Workshop and FXFOWLE Architects, with Gensler providing interior design. The tower rises 748 feet (228 m) from the street to its roof, with the exterior curtain wall extending 92 feet higher to 840 feet (256 m), and a mast rising to 1,046 feet (319 m). The building is currently tied with the Chrysler Building as the second tallest building in New York and the 6th tallest in the United States. The steel-framed building, cruciform in plan, utilizes a screen of 1-5/8" (41.3mm) ceramic rods mounted on the exterior of the glass curtain wall on the east, west and south facades. The rod spacing increases from the base to the top, providing greater transparency as the building rises. The steel framing and bracing is exposed at the four corner "notches" of the building.[3] Sustainability The building is promoted as a "Green" structure, though it is not LEED certified. The design incorporates many features for increased energy efficiency. The curtain wall, fully glazed with low-e glass, maximizes natural light within the building while the ceramic-rod screen helps block direct sunlight and reduce cooling loads. Mechanized shades controlled by sensors reduce glare, while more than 18,000 individually-dimmable fluorescent fixtures supplement natural light, providing a real energy savings of 30 percent.[4][5] A natural gas co-generation plant provides 40 percent of the electrical power to the New York Times space within the building, with the waste heat used for heating and cooling. Floors occupied by the New York Times utilize a raised floor system which allows for underfloor air distribution, which requires less cooling than a conventional ducted system. The building also incorporated free-air cooling, bringing in outside air when it is cooler than the interior space, which saves additional energy.[4] The story of the tower's construction is showcased at the Liberty Science Center's exhibition "Skyscraper! Achievement and Impact". Tenants The New York Times Company owns about 800,000 square feet (74,300 square meters) on the second through the 27th floors. Forest City Ratner owns about 700,000 square feet (65,032 square meters) on floors 29 through 52, as well as 21,000 square feet (1,951 square meters) of street-level retail space. The lobby and floors 28 and 51 are jointly owned. Four law firms have their offices in the building: Covington & Burling LLP; Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP (36th floor); Pepper Hamilton LLP (37th floor); and Seyfarth Shaw LLP (31st-33rd floors).[4] In 2008, the law firm of Goodwin Procter LLP will move into the building (leasing floors 23-27 from the New York Times and floors 29-30 from FCRC). Other office tenants include: Barclays Center/New Jersey Nets, JAMS, Legg Mason, Markit Group Limited, The Resolution Experts, Samoo Architecture P.C., and SJP Properties. Retail tenants include: Inakaya, Dean & Deluca, and MUJI. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|