|

New York

Architecture Images- Midtown The B. Altman Department Store |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

architect |

Trowbridge & Livingston | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

location |

covers the entire city block bounded by Fifth and Madison Avenues, and East 34th and 35th Streets | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

date |

1905 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

style |

Renaissance Revival | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

construction |

French limestone | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

type |

Shop | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

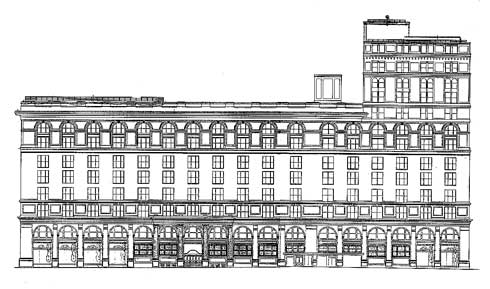

Trowbridge & Livingston also designed a number of residential buildings in a variety of styles popular at the time, including the neo-Federal, the Beaux-Arts, and the neo-Italian Renaissance. A number of handsome examples can be found on Manhattan's Upper East Side, including Nos. 49 East 68th Street, 123 East 63rd Street, and 123 East 70th Street. In these houses the architects used a variety of materials, often combining a rusticated limestone base with brick upper stories and a copper-edged mansard roof. They also used a variety of decorative elements, enriching their facades with iron balustrades, carved garlands, escutcheons, medallions, and elaborate pedimented window surrounds. Description Trowbridge & Livingston's background in both dignified public buildings and elegant private town houses provided an ideal combination for the design of B. Altman. Although a large department store, the building was apparently designed to match the architectural character of the surrounding neighborhood. Trowbridge & Livingston succeeded in making the transition from residential to commercial as painless, architecturally speaking, as possible. This was accomplished by basing the architectural treatment of the enormous store on the same Italianate palazzo models that had been used, not only by prior department stores, but also by so many of the large private mansions lining Fifth Avenue, as for instance the A.T. Stewart home across the street. The French limestone walls - the first use on a commercial structure of a material heretofore reserved for residential buildings - the aedicular windows, broad overhanging cornice, and elegant detailing, all helped B. Altman gracefully blend into the neighborhood. Built in stages, B. Altman today covers the entire city block bounded by Fifth and Madison Avenues, and East 34th and 35th Streets. Eight stories tall on Fifth Avenue and on most of the side-street frontages, B. Altman rises to thirteen stories on Madison. Fifth Avenue facade:  The B. Altman Fifth Avenue facade is nine bays wide and eight stories tall, faced in limestone which has been repaired with cast-stone patches. The first and second stories are united into a base for the facade by a colonnade formed of a giant order of what were originally engaged Ionic columns, unfluted, supporting an architrave now stripped of its detail. The columns sit on pedestals, which increase

in height along the southward slope of Fifth Avenue. The central three bays project to form a grand portico enclosing the store's main entrance. The columns of the portico are more elaborate than the others; they are fluted, the intrados of their arches are adorned with roundels, and their bases have ornamental moldings in a

modified Greek fret design. Their original Ionic capitals have been replaced by rosettes. Within the bays formed by the double-height columns of the colonnade, single-height engaged piers flanking windows and doors support an arch whose apex touches the architrave. On either side of the entrance portico, the two-story bays are divided into upper and lower windows, separated by an architrave. The lower, first-story window is a sheet of glass serving as a display window, above which is a canopy and its housing surmounted by a blank area of glass. The upper windows are in the configuration of a Roman Bath window, semi-circular and divided into six lights, actually comprising three one-over-one double-hung sash. The three-entrance-portico bays repeat this window configuration at the second-story level, but in place of display windows, the first-story level has entrances, approached by a stone staircase. In the central bay, at the first-story level, there are three pairs of doors, in their original configuration, topped by a transom; in the bay to either side there is one set of doors and a display window. Above each entrance is a curving, Art Nouveau style metal and glass canopy, supported by elaborate wrought-metal brackets. Beneath, a metal frieze runs above the entrance and

display-window. In each of these three bays, above the canopy but below the architrave separating the first from the second story, the bay is filled in with panels of glass. The third-story level of the Fifth Avenue facade comprises a series of square-headed windows corresponding to the nine bays below. They have simple molded surrounds with a keystone at the center top; the window glass consists of three one-over-one double-hung windows, with the center windows wider than those at the sides. Between the window openings, over the giant columns below, are large square panels with molded edges. A band-course runs above the windows, separating this story from the next three above it. The windows in the fourth through sixth-story levels are now almost identical to those at the third-story level. They have simple sills, and no keystones. Originally each had a molded surround, and was connected to the window above by a lintel supported on console brackets; these, however, were later removed, and the windows today are plain. Above the sixth-story level runs an architrave with a frieze with triglyphs. The seventh and eighth stories are treated visually as a double story, mirroring the two-story base. Each bay comprises a double-height arched window, with a lower seventh-story window separated from the upper eighth-story window by a horizontal element. The seventh-story window follows the configuration of the windows directly below; the Eighth-story window is a Roman Bath-type configuration, similar to that at the second-story level: three one-over-one double-hung sash. Above the eighth-story level is an entablature and heavy cornice. Guttae depnd from the entablature; at the top of the cornice, marking each bay, is a decorative lion's head.

East 34th Street facade:  The East 34th Street facade is similar in design to the Fifth Avenue facade, with the following exceptions: This facade comprises a much longer street frontage than that on Fifth Avenue, and is divided into bays as follows: from Fifth Avenue, five bays, followed by a projecting three-bay entrance portico, beyond which stretch nine more bays. Except in the entrance portico, the double-height columns of Fifth Avenue are replaced by pilasters. The entrance portico is similar to that on Fifth Avenue, but only its center bay has an entrance with elaborate canopy and staircase. Only the first four bays east from Fifth Avenue, and the first two bays west from Madison Avenue, contain display-windows. In the other bays, the area corresponding to the display windows is divided into two portions: in the upper, there are three double-hung one-over-one sash behind a metal grille; in the lower, there is a stone panel over a base. The eleventh and twelfth bays east from Fifth Avenue serve as a service entrance; they have a simple functional canopy above them. The four eastern bays of the East 34th Street facade rise to a thirteen-story tower. The treatment of the first eight stories is identical to their treatment in the western bays; the upper five stories, faced in brick rather than in limestone, are handled as follows: the ninth story, at the level of the cornice to the west, comprises paired double-hung one-over-one windows, above which is a band course. The tenth and eleventh stories are treated as a unit, with paired double-hung one-over-one windows, recessed; within the recess, the windows are separated by a slender double-height Ionic column and architrave, from which spring small arches. A band course separates these windows from the twelfth-story level, which is identical in treatment to the ninth-story level. A corbelled band course in turn separates the twelfth from the thirteenth story, which has similar window treatment; the thirteenth story is capped by a small cornice. Madison Avenue facade: The Madison Avenue facade is related in design to the Fifth Avenue facade, but is not identical. The first and second stories form a base similar to that on Fifth Avenue, but have no projecting central portico. Instead, the single bay at either end projects slightly. The central bay of the facade has a single entrance, with an elaborate ornamental canopy matching those on Fifth Avenue. The end bay at either corner is limestone-faced with cast-stone patches from the first to the eighth stories, and brick-faced above. The inner bays are limestone-faced only at the first two stories, and brick-faced above. The end bays are further distinguished from the inner bays by having narrower windows, and hence being heavier in appearance, creating the effect of end pavilions. The brick-faced inner bays are treated as follows: The third-story level consists of paired double-hung one-over-one windows. The fourth- through sixth-story bays are treated as a three-story unit, comprising three-story brick piers supporting a stone architrave. Within the brick piers, the windows are divided further into three small bays by a metal framework. At the fourth-story level in each bay, the three smaller bays are formed by two slender Corinthian columns on tall pedestals, supporting an architrave; the architrave breaks forward over the central small bay and supports a segmental pediment. This form is repeated at the fifth-story level with Ionic columns and an architrave, but with no pediment or pedestals; it is repeated again at the sixth-story level with no architrave, pediment or pedestals, but with console brackets supported by the columns. The seventh- and eighth-story levels, separated from the lower levels by an architrave, are treated as a double-height arcade defined by brick piers, with a paneled effect; the brick arches have stone-faced keystones. Within the piers, at the seventh-story level, the window is divided into three smaller bays, of double-hung one-over-one sash, defined by slender colonnettes; the-sash at the eighth-story level are in a Roman Bath window configuration. At the ninth-story level, each bay consists of a pair of square-headed one-over-one double-hung windows. The tenth and eleventh stories are a modified reprise of the design of the fourth- through sixth-story levels: two-story, double-hung one-over-one paired sash, separated by Ionic columns from which spring small arches. The twelfth-story bays comprise square-headed one-over-one double-hung windows, above which is a level of brick corbelling. The final, thirteenth-story bays comprise paired double-hung windows topped by a small cornice. The stone-faced outer bays above the second-story level are treated as follows: At the third- through sixth-story levels, the windows are comprised of three double-hung one-over-one sash with a wide central portion and narrow sides. The seventh- and eighth-story levels have windows which in design are a modified version of those at the same level in the inner bays. The ninth to thirteenth-story levels are brick-faced, with narrower versions of the windows of the inner bays at the same level. East 35th Street facade: The East 35th Street facade is similar to that on East 34th Street, but different in certain details; East 34th Street is a major cross-town artery, and therefore its facade has a somewhat more elaborate treatment than that on East 35th Street, as well as a major entrance. The bays in the two-story base along East 35th Street, from Fifth to Madison Avenue, include: three bays of display-windows, a fourth-bay single entrance, eight bays of windows behind grilles, a service entrance in the thirteenth bay, a loading bay in the fourteenth bay, windows behind grilles and a service entrance in the fifteenth bay, a window behind a grille in the sixteenth bay, and a display-window in the seventeenth bay at the corner of Madison Avenue. The fourth-bay entrance has a projecting metal entrance porch comprising three sets of doors under an entablature with a classical frieze; the entablature is supported at either end by elaborate metal piers. Transoms above are topped by a cornice and simple pediment. The thirteenth- and fifteenth-bay entrances now have nondescript shelters in front of them. Above the two-story base, the treatment of the East 35th Street facade is similar to that on East 34th Street. Utility sheds on the roof are partially visible. Conclusion B. Altman opened to critical acclaim. "The architecture is classic," wrote a critic from the New York Times, "doorway and entrance columns are handsomely decorated.... The store adds materially to the beauty of Fifth Avenue."32 The building was, and remains, a powerful presence on the Avenue, eloquent testimony to B. Altman's position as a pathbreaker in the development of Fifth Avenue in Midtown. After Benjamin Altman's death in 1913, just a year after completion of the Madison Avenue extension to his store, it continued in operation, but under an unusual arrangement.33 Altman's will, besides providing for the donation of his art collection to the Metropolitan Museum, also created an "Altman Foundation" whose purpose was to run the store to promote the social, physical or economic welfare and efficiency of the employees of B. Altman and Company... and to the use and benefit of charitable, benevolent or educational institutions within the state of New York.34 The idea of running the store to benefit its employees was consistent with Benjamin Altman's history of enlightened employee treatment.35 As other large department stores followed Altman's lead, Fifth Avenue, as predicted, was transformed into New York's premier shopping street, lined from 34th to 59th Streets with stores that became flagships for such national chains as Saks Fifth Avenue, Bergdorf-Goodman, Lord & Taylor, and many others not all of which survive. B. Altman's elegant structure at 34th Street, first to be built, came to serve as the grand entrance to the Fifth Avenue shopping corridor. Today, although the B. Altman building has undergone some renovations due to the deterioration of the limestone, it remains essentially intact. Spalls have been patched with cast stone instead of limestone. Column capitals at the ground floor have been removed, as have the fourth- and fifth-story lintels. Band courses and roof cornices have been simplified. Yet the basic design elements, including the beautifully ornate entrances, survive unchanged. And the atmosphere of "middle" Fifth Avenue, set by the opening of B. Altman almost eighty years ago, survives as well. The B. Altman & Company building remains an exemplar of American neo-Renaissance commercial design, and a landmark in the cultural history of New York. Report prepared by Sarah Williams Volunteer Supervised by Anthony W. Robins Deputy Director of Research See also the Soho B. Altman Dry Goods Store |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| www.gc.cuny.edu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||