| New York

Architecture Images- Recent Vision Machine |

|

| Please note- I do not own the copyright for the images on this page. | |

|

architect |

Jean Nouvel |

|

location |

100-110 Eleventh Avenue / 535-541 West 19th Street |

|

date |

2008 |

|

style |

Crafted Modernism |

|

type |

Apartment Building |

|

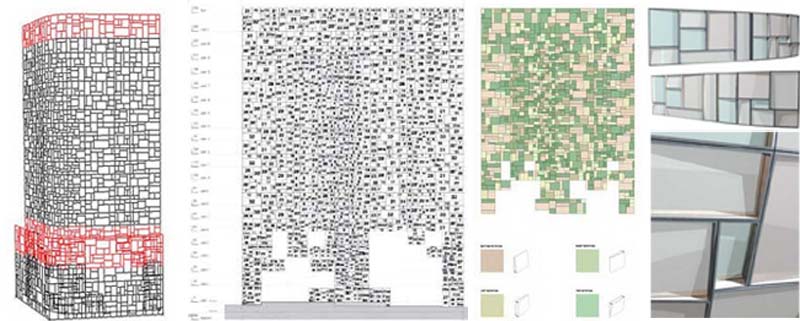

construction |

The main south curtain wall is comprised of approximately 1,647 completely different colorless windowpanes organized within enormous steel-framed “megapanels” that range from 11 to 16 feet tall and as wide as 37 feet across. Each windowpane inside these megapanels is tilted at a different angle and in a different direction. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

notes |

The Building Declaring, “Each new situation requires a new architecture,” Jean Nouvel has ambushed conventional tower design by forming the building’s mass along a curve that traces the entire breadth of its site. This gesture maximizes both street frontage and views from within the building, insuring that all of the residences at 100 11th have full access to south and west views and light. From the smallest to the largest, every single residence in the building will enjoy a sweep of uninterrupted floor-to-ceiling window wall — from 35 to 175 linear feet — on the main façade.  Every angle and structural detail at 100 11th has been designed to create visual excitement for the both those living within the tower and passers-by on the street. The main south curtain wall is comprised of approximately 1,647 completely different colorless windowpanes organized within enormous steel-framed “megapanels” that range from 11 to 16 feet tall and as wide as 37 feet across. Each windowpane inside these megapanels is tilted at a different angle and in a different direction — up, down, in, out - bearing a slightly different degree of transparency according to a system meticulously developed by Ateliers Jean Nouvel and inspired in part by the renowned stained-glass window cycles of the 13th century Gothic cathedral of Sainte-Chapelle in Paris. The result of Nouvel’s system is a composition with a structural purpose in the service of the architect’s primary goal: framing views within residences while producing a poetic public statement about the inherent beauty of the fragmented, varied, ever-changing life of New York City and its island relationship to water and sky.  By contrast, the north and east façades of 100 11th will be clad in black brick that references the masonry characteristic of West Chelsea’s industrial architecture. These façades will also contain a complex and beautiful pattern of different-sized punched windows framing dramatic views from inside. On the north façade, the building will also express motion within: Elevator shafts will contain random LED lighting and full-scale punched windows, so that passengers in glass-walled cabs can see city vistas as they ascend at 450 feet per minute, while twinkling light patterns are visible from elsewhere in the neighborhood. Residents of 100 11th will enter the building through a door on 19th Street and a transitional vestibule, into a dramatic lobby space with 20 foot-high ceilings. Like the south façade, this space traces the full breadth of the site. Within this main lobby, bright exterior reflections will give way to a contemplative atmosphere of low, soft lighting via fixtures custom designed by Jean Nouvel. Enormous, single-pane punched windows of different textures and degrees of transparency will face the building’s private multi-tiered slope garden on the north side of the building, bringing nature indoors. The lobby will also include stations for a 24-hour doorman and concierge, with custom millwork desks designed by Jean Nouvel; access to a ground-floor restaurant and dining patio; private residents’ mail room, package and refrigerated storage room; private residents’ automatic bank teller; access to the garden; and a private elevator landing serving the residences above and the gym, spa and pool area below.  At 70 feet long, the building’s mirror-canopied pool will be one of the longest in Manhattan. The majority of the pool is sheltered within the building’s structure, with 24 feet extending into a landscaped outdoor space (the lower tier of the garden). A state-of-the-art glass partition has been customized by Nouvel to enclose the indoor portion of the pool so that residents can enjoy it all year, regardless of weather. A fitness center includes spa facilities (steam room, sauna, and individual changing cabanas with showers) and a private residents’ lounge that looks out over the lower level of the garden. Adjacent to the lounge and fitness area will be a private screening room for residents. The Loggia At 100 11th, Nouvel has conceived one of the most creative and revolutionary solutions to the challenges of low-floor dwelling ever seen in New York City. At a distance of 15 feet from the building’s south façade, he has placed a free-standing “screen” of densely mullioned glass — a near repeat of the main façade’s steel-framed mosaic pattern — rising seven stories. The space created between the tower’s multifaceted glass curtain wall and this street wall screen forms a semi-enclosed atrium called “The Loggia,” containing a complex structural steel grid. The grid will contain a world unto itself, a space unlike any other in New York City, to be shared exclusively by the residents of the building’s Loggia Residences on first seven floors. Here, every apartment enjoys a unique floor plan. Terraces — some enclosed and others open to the space — grace various apartments in the atrium. Fully grown trees and beds of ornamental plantings will be placed within the grid in an imaginative system of containers that appear to float in mid-air. Loggia terraces are all designed as year-round, indoor-outdoor spaces, with floor to ceiling glass on at least three sides and in-floor radiant heat. The Residences According to Beyer Blinder Belle partner John H. Beyer, “Jean Nouvel has a unique understanding of the way light and water work together to create constantly oscillating effects of reflection and shadow, and a special talent for using daylight as an architectural material.” At 100 11th, these special skills will be fully experienced withinthe residences of the building, where spatial organization and material applications are entirely in the service of views and the pleasure of natural light that changes over the course of days and seasons. Every apartment within 100 11th will boast a completely different pattern of powder-coated steel window mullions — a unique “fingerprint” — framing views and providing operable windows. Along these window walls, floors will be finished with an extra layer of nearly imperceptible transparent gloss that will boost incoming sunlight into rooms. Mechanized shade systems, customized by Nouvel, will allow residents to modulate and control the flow of daylight into spaces and further frame specific views. The palette of apartment interiors is pale and materials have been chosen to achieve maximum luminosity, with an overall look inspired by the sleek minimalism of the neighborhood’s many contemporary art galleries. Serene refuges for living with views and art, the apartments are highly disciplined, super-customized, luxurious combinations of white terrazzo flooring, white plaster walls, pale steel window framing, and a palette of carefully selected white and stainless steel materials in discreet kitchensand baths custom designed by Nouvel. Walls feature pocket doors and large-scale pivot doors that allow for increased flow of light and air between spaces. Interior architectural details have been conceived to amplify the light that pours into every residence: Angled beams taper as they recede into the rooms, encouraging the flow of light. The finishes on floors are more reflective in areas close to windows to boost illumination. Carefully crafted fixture plans include niche lighting, indirect lighting, and exposed light sources, all custom designed by Jean Nouvel. Open curved and rectilinear spaces throughout the residences were conceived to allow for the broadest possible variety of furniture configurations that take advantage of light and views. Kitchens flow spatially into open living areas, and are designed with luxury fixtures custom designed by Jean Nouvel to achieve the highest level of design excellence and to compliment art and furniture. These generously proportioned environments, composed of stainless steel, etched and clear glass, white terrazzo and custom lighting, encompass three “zones”: a pantry, a food preparation area with custom designed islands containing detachable rolling storage carts, and a cooking area with top line appliances. Similarly, bathrooms at 100 11th are studies in luxury customization, with pale, gleaming materials palettes (Nouvel-conceived geometric compositions of Corian, spandrel glass, fritted glass, porcelain, painted plaster and mirrors) developed for aesthetic continuity with the rest of the residence. Fixtures have been custom designed by Jean Nouvel for Jado. “The task of the architect is to encompass everything about the site, starting from the concrete conditions and the sensory impressions created by those, to memories of the place, through empathy to vision,” Nouvel has said. At 100 11th, the architect has translated this notion into extraordinary residences in a building with deep urban meaning, luminosity, and the high-technology innovations that have become his trademark in the two decades since his Arab World Institute opened to the public. The sales and design center for 100 11th is located two blocks north of the building site, at 547 West 21st Street, between Tenth Avenue and the West Side Highway. --------------- 100 11th Ave: Vision Machine - by Jean Nouvel 100-110 Eleventh Avenue / 535-541 West 19th Street 21 stories 250 feet (DoB) Architect: Atelier Jean Nouvel Executive Architect: Beyer Blinder Belle Architects & Planners, LLP Developer: Cape Advisors Inc/Craig Wood Associate Developer: Alf Naman Real Estate Advisors Residential Condominium 143,289 Sq. Ft. 72 units Under Construction: Fall 2006 - Fall 2008 http://www.nouvelchelsea.com/ ----------------------- Jean Nouvel's ‘Vision' Rising in Chelsea By DAVID FREEDLANDER, Special to the Sun | April 5, 2007 A gray strip of West Chelsea is about to become the capital of bold architecture in Manhattan. In one corner, the undulating curves of Frank Gehry's new IAC building. And now facing it, Jean Nouvel's "Vision Machine," a 23-story glittering glass residential tower at the 19th Street and the West Side Highway, which broke ground this week. The project's developers, Cape Advisors, are betting that buyers are willing to pay extra to live in the iconic-looking structure. Apartments in the 72-unit building will range from $1.6 million to $22 million. The development is part of a growing trend of star architects lending their name and design prowess to residential structures in New York. "Buyers have become extremely sophisticated because the market has changed so dramatically," the marketing and sales agent for the property, James Lansill of the Corcoran Sunshine Marketing Group, said. " A large percentage of what a new buyer looks at now is future construction and things in process. Buyers have gotten very sophisticated about seeing distinctions among different properties." Some of the amenities at the building to rise at 100 11th Avenue include white terrazzo floors within each residence, a 70-foot half-indoor, half-outdoor swimming pool separated by a glass partition, and terraces opening onto a seven-story hanging garden loggia of ornamental plants and trees. The project also features an on-site concierge, a private spa with steam rooms and a sauna, and a high-end restaurant on the ground floor, which early rumors have pegged to Union Square Café's Danny Meyer. A project spokesman said discussions on the restaurant site are still ongoing. "We're strong believers that design pays and that people are willing to pay a premium for design," Craig Wood of Cape Advisors, said. "Jean designed everything in every room and put a tremendous level of energy into the innermost details." "You haven't really seen anything like this in New York in recent times," Mr. Wood continued. "You see it in other cities, or with cultural institutions and office buildings in New York. It's one of the most important residential buildings done in the city in the past fifty years." Mr. Nouvel is known for avoiding a signature style, and instead designs each project to fit its unique surroundings, according to Jack Beyer of Beyer, Blinder, Belle, the executive architects for 100 11th Avenue. "Unlike other renowned architectural stars, he deals with the context of building in a way that's special and site-specific," Mr. Beyer said in an interview. "All of his projects are different. They don't ring out a branded look." The building's curtain wall contains nearly 1,700 pieces of glass, each uniquely sized and jutting out from the structure at odd angles and catching the sky and light of the city at different angles throughout the day. "This kind of glass housing tells you about the kind of democracy and transparency that all of our society should have," the executive director of the New York chapter of the American Institute of Architects, Rick Bell, said. "The building is not walling itself off from the city. It's not a fortress turning its back on the street. His use of light and glass reflects and refracts the life of the city going on around it." Unlike other projects in the city where developers wrestle with the architects to keep costs as low as possible, sometimes doing little more than slapping the boldfaced name of a well-known designer onto sales literature, 100 11th Avenue is Nouvel throughout, from the light fixtures to the cabinets to the placement of windows that maximize views of the city and river. "The client here wants everything they could possibly get in the way that Nouvel delivered it," Mr. Beyer said "It's not just the façade but the entire building, every bit of it. It's a true craftsman experience which is very rare in today's world of residential construction." The building is scheduled to open in the fall of 2008. Source- http://www.nysun.com/real-estate/jean-nouvels-vision-rising-in-chelsea/51896/ |

|

|

|

|

|

Architecture Review | Jean Nouvel By NICOLAI OUROUSSOFF At the Corner of Grit and Glamour During the past few years Chelsea became a one-stop-shopping destination for high-style contemporary architecture as well as high-end art, and the results can be depressing. For every significant building that went up, the neighborhood seemed to produce a half-dozen or so inferior knockoffs. The feeling on the streets now is the same as it is in most of the galleries: the sheer amount of work, and the mediocrity of most of it, can make the effort of sorting out the good from the bad too painful to contemplate. So Jean Nouvel’s new residential tower — at the western end of 19th Street, unveiled at an event this month — is a relief of sorts. It is a luxury building, and who would argue that we need more of those? But its mix of grit and glamour — embodied in a glittering facade that seems to have been wrapped around the curved front of a black brick tower like a tight-fitting sequined dress — is apt to temper whatever you may feel about the Wall Streeters and art-world insiders who are likely to move into its apartments. It conjures a downtown New York we once loved and can now barely remember, where rundown manufacturing buildings buzzed with cultural vitality. The building’s rough-edged sex appeal may actually overshadow what’s best about the project, the remarkable skill with which Mr. Nouvel embeds it into its surroundings. Rising on the brief stretch of 11th Avenue that doubles as the West Side Highway, directly across the street from the billowing glass forms of Frank Gehry’s IAC building and abutting a somber brick women’s prison on the other side, the tower is part of a taut composition of disparate — even conflicting — urban realities. Its shifting appearance in the skyline is a sly commentary on the conflict between public and private realms that is an inevitable byproduct of gentrification. That process has become particularly savage in New York, a city divided between big development companies that see architectural novelty as a tool for inflating prices for their luxury projects, and local activists who have marginalized themselves by their refusal to accept any kind of change at all. (If the financial collapse has slowed this trend, it has done little to alter the mentalities behind it.) Mr. Nouvel did not invent that world, but he knows that his name is used to sell real estate, and he understands that fashionable forms can disguise the damage caused by heedless market forces behind a gloss of radical chic. Like many of his generation — Mr. Nouvel is 64 — he retains a stubborn, some might say naïve, belief that architecture should make us alert to the conflicts that shape the modern city rather than conceal them. That attitude is apparent in the mixed signals the building sends. Seen from across the West Side Highway, the tower’s twinkling facade, with its hundreds of irregularly shaped windows tilted at odd angles to reflect fragments of sky or the surrounding city, offers a striking counterpoint to the soft, sail-like curves of Mr. Gehry’s creation. Rows of older brick buildings flank them to the north and south, and the contrast between glass and masonry, straight and curved lines, creates a nice rhythm along what was once a bleak strip of decrepit offices and warehouses. I prefer the view from the east, however, along West 19th Street. The side of the building is made of matte-black bricks and punctured by a few small sporadic windows, evoking the unadorned backsides of prewar tenements. All you see of the main glass facade is a thin sliver of steel running along its front edge. As you approach the corner, the facade’s riotous forms suddenly come into view, and it’s startling. Close up, the steel frames that support the windows look beefier, and the effect is more frenetic. A second glass-and-steel screen wraps around the building’s lower floors. Supported on a heavy concrete base, the frames of this screen interlock at the street corner like interwoven fingers, enclosing a small open-air terrace that will serve a ground-floor restaurant and bar. These spaces have no tenants yet, and for now remain hidden behind fencing and construction equipment. Some of the window frames have been left intentionally empty, so that it may take a moment to sort out whether you’re indoors or out. A network of heavy steel beams reaching up several stories connects the screen back to the main facade; the beams will eventually support big planters containing trees that will seem to hover in midair. It’s a nice surrealistic touch. Yet the punched-out windows and ragged corner also suggest an erosion of the boundary between the public life of the street and the guarded, private realm inside. The future restaurant’s terrace is made of the same concrete as the sidewalk, as if to suggest that it really belongs to the city. Glass-enclosed terraces off the lower-floor apartments will push out into the space of the elevated trees, as if the building’s residents were reaching out to grab more for themselves. These same tensions continue to play out inside. There’s a sexiness to the main lobby, with its floors and walls of sleek black granite and painted glass, and its fleeting view of a swimming pool set between the tower and the back of the older brick building behind it. Once you get to the apartments, however, that eroticism is mixed with a certain urban toughness. Details are simple and straightforward (despite the Viking stoves). The apartment terraces are reached through pivoting, industrial-scale doors. Mr. Nouvel imagines the terraces filling up with potted plants, bicycles and other odds and ends once the tenants have settled in. Conversely, the backs of the apartments have small cut-out windows placed at odd heights — some at eye level, others up near the ceiling — that frame contrasting views of the city: the clock on the old Metropolitan Life Tower; a caged recreational area on the roof of the prison; a sooty brick wall covered with pipes, the Empire State Building. The care with which the views are framed — reinforced by the windows’ simple heavy steel borders — is such that you can almost feel the city tugging at you. (The penthouse, not surprisingly, is the least seductive of all the apartments. Vast and airy, it could have been shaped by a real estate agent’s checklist. Sweeping river views, marble fireplaces, walk-in closets: these are today’s equivalent of gold faucets and sunken tubs.) Some will argue that all of this simply provides a veneer of civility to a culture that is sliding deeper and deeper into narcissism. For me, though, the building is a lesson on how to navigate an enlightened path in an era of extremes. It’s not utopia, but it demonstrates what a major talent can accomplish when he focuses his mind on a small corner of the city. Source- http://www.nytimes.com |

|

|

|