|

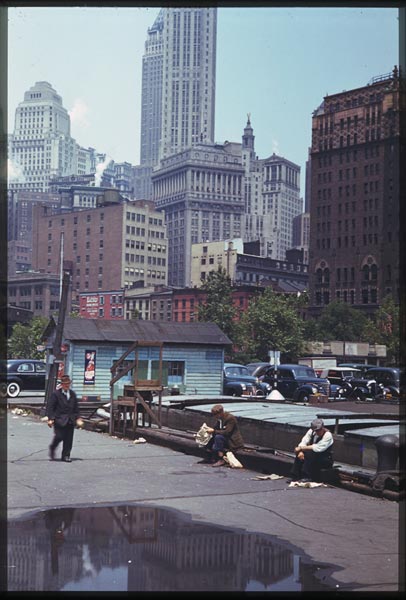

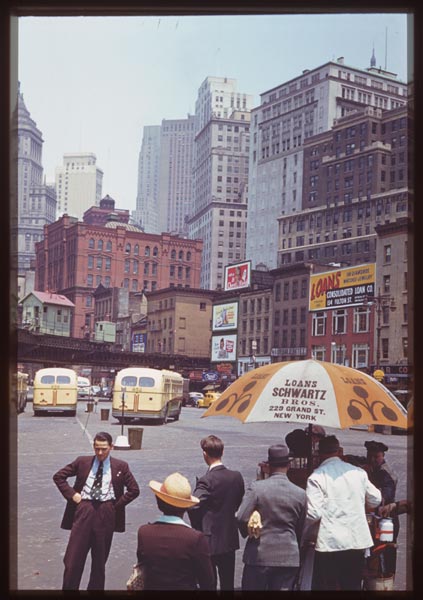

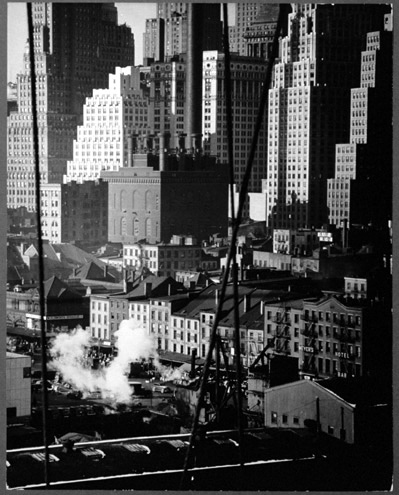

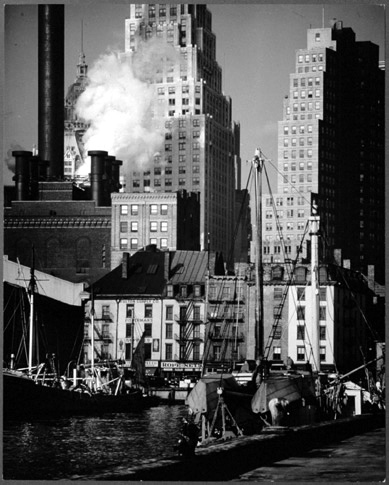

New York

Architecture Images-Seaport and Civic Center Fulton Fish Market |

||||||||||||

|

architect |

Benjamin Thompson |

||||||||||||

|

location |

Fulton Street (bet. Pier 17 and the Brooklyn Bridge) | ||||||||||||

|

date |

Established 1821 | ||||||||||||

|

type |

Utility market | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

notes |

|

||||||||||||

|

TRIBECA TRIBUNE:

A Tide Turns At the Seaport by Carl Glassman For many years, the empty, weathered warehouses on Front Street and around the corner on Peck Slip—seaport denizens since the beginning of the 19th century—have been standing, just barely, waiting to be saved.   Some couldn’t hold on. Facades peeled away to the ground. Roofs fell in. But for those that remain, their fronts netted to catch crumbling brick, hope lies in the plans of developers Zuberry Associates and Sciame Construction to preserve this important block of the old fish market. The buildings, some dating to 1798, lie in the South Street Seaport Historic District. Architect Richard Cook, whose diverse projects range from P.S./I.S. 89 to the Caroline apartments at 23rd Street and Sixth Avenue and an office tower at 360 Madison Ave., presented the $48 million project to the Landmarks Preservation Commission on April 1. In a rare action, the commission approved the project, en masse, at the first hearing. The plans call for restoring 11 buildings and constructing three new ones, creating a total of nearly 100 rental apartments. Funding is aided by preservation tax credits and federally financed Liberty Bonds, meant to promote the revival of Lower Manhattan. The city-owned properties, which the developers can purchase only after city approvals, have languished for 20 years as the Economic Development Corp. tried to orchestrate their redevelopment. In 1988, the city agreed to lease the buildings to Metropolis Group, but that company never moved forward with their development plans, leading to a long legal battle. In 1997, the city won back the development rights to the block and three years later selected Bohn Fiore Inc. as the new developer. But the company failed to get financing and the city removed them from the project in 2001. Last May, the EDC chose Sciame and Zuberry, with the support of neighborhood residents and Community Board 1. But in the meantime, several buildings have been lost and others are perilously close to collapse. One is so hazardous that the developers and architect have yet to see the inside.   *“These are in such horrible condition. There’s something romantic about that,” said Cook, as he inspected the interior of one of the Front Street buildings last month, his path lit by bulbs recently strung from the rafters. Large unsafe sections of the floors were cordoned off by yellow tape. Unlike the warehouses of Tribeca, built some 80 years later, the ceilings of these old seaport buildings are low, and the wood is, as Cook puts it, “another degree of ancient.” He wants to preserve the feeling of antiquity by keeping the patina of peeling paint and turning existing remnants such as wooden columns into sculptural elements. During this visit, he discovers a giant wheel on the top floor, part of the building’s timber-framed hoist. He asks Zuberry’s Anthony Zunino, who accompanies him, if he can incorporate it in the apartment plan, maybe as part of the breakfast nook. “Sure,” Zunino says. Cook smiles. “So that’s okay? You could do that? Great. A decision.” Cook’s romance with the seaport extends to the new buildings he has designed there. The plan for 24 Peck Slip includes canopy cables on the facade that suggest the rigging of a sailing ship. But its contemporary lines are not meant to resemble neighboring buildings. “We’re hoping that [the design] speaks more about these ghosts of the South Street Seaport than the specifics of lintels and mullions and bricks and mortar,” he says. Cook says the presence of those seaport ghosts—salty remnants of the city’s early maritime history—helps drive this complex project and, one day, will bring people to live there. “This is the real stuff,” he says. “You can literally smell it in the air.”    |

|||||||||||||

|

July 3, 2003 Development in a Historic District: New Life on a Street Left for Dead By DAVID W. DUNLAP These are the very streets that Melville wrote about," said Richard A. Cook of Cook + Fox Architects. "A land that time forgot." Not just time. One developer after another has forgotten a pungent, poignant stretch of Front Street in Lower Manhattan, rather than try to weave new buildings among landmark 19th-century brick counting houses. Undaunted, a group including Frank J. Sciame Jr. of Sciame Development, an experienced builder in the South Street Seaport Historic District, and F. Anthony Zunino III and Richard S. Berry of Zuberry Associates, bought the properties last week and closed on a $46.3 million Liberty Bond. They plan to rehabilitate 11 historical buildings on Front Street and Peck Slip and construct three new buildings, creating 96 rental apartments, 18,750 square feet of small-scale retail space and a 3,500-square foot maritime center. The new buildings will rise on what are now vacant lots. Work will begin this month and should be finished in less than a year and a half, Mr. Sciame said. Through abstract references, the new buildings are meant to pay homage to the maritime past. A shallow V-shaped roof atop 213 Front Street will conjure a whale fluke. Timber slats at 24 and 36 Peck Slip will evoke the ships that moored there when the slip was a waterfront berth. "We talked a lot about things that were relevant but no longer tangible," Mr. Cook said, describing the existing buildings, some of which date to the early 1800's, as being in "a romantic state of collapse." To which Mr. Berry, so drained by the closing earlier that day that he could no longer legibly form his own signature, said, "How romantic is that?" Actually, romantic enough that historical layers will be preserved. "This will be like no other place to live," Mr. Zunino said. Exhibit A: even after renovation, 225 Front Street will still be encrusted with the fading remnants of hand-painted signs for "House of Fillet," "Mild Cure" and "Salmon." Rents are expected to range from $2,000 to $2,500 a month for one-bedroom apartments with 648 to 975 square feet of space, and $3,500 to $4,000 a month for two-bedroom units with 989 to 1,218 square feet. Interest on the bonds, issued by the state's Housing Finance Agency, are exempt from taxes under the $8 billion Liberty Bond program for redeveloping Lower Manhattan. Andrew M. Alper, president of the city's Economic Development Corporation, which sold the properties for $5 million, said through a spokeswoman that the developers had "extensive experience in completing similar challenging projects," noting Mr. Sciame's rehabilitation of 247 and 273 Water Street. Since their tentative designation last summer, Sciame and Zuberry have been joined by the Durst Organization. The developers have chosen to build considerably less floor area — 147,383 square feet in total — than zoning rules would have allowed. That was one reason Community Board 1 was "thrilled" by the project, said its chairwoman, Madelyn Wils. "It needed to be a labor of love more than a labor for profit," she said. "These buildings have fallen apart over the last 15 years." The Landmarks Preservation Commission approved the project in April after a single hearing. Reflecting on the years of stop-and-go projects, Roberta Brandes Gratz, a commission member, said: "Sometimes delay works for the better. I can't imagine a better plan."  Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company

October 2, 2003

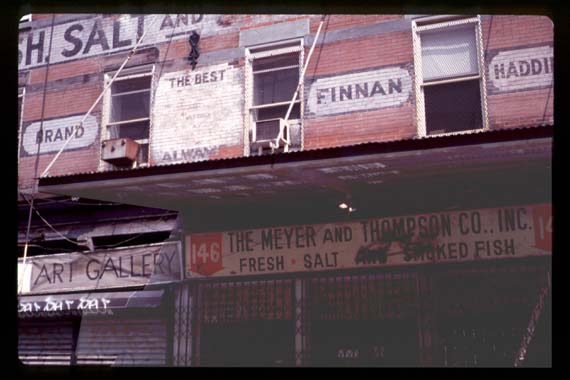

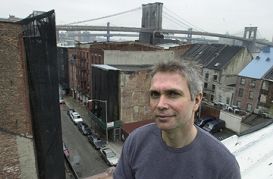

Where a Fresh-Caught Fish Is the Best Neighbor By JOHN LELAND  Slide Show: A Sense of Old New York  THERE are several ways to consider the fish smell that hangs over the stone-paved streets by the Fulton Fish Market in Lower Manhattan. One is as a seasonal calendar, its pungency changing with the tides and temperature. On a wind-swept block near the market the other day, Gary Fagin, 51, offered a different take. Mr. Fagin, a musician, has lived near the market since 1986, and some neighbors refer to him as Mayor. He described the aroma as a kind of protective talisman that shields the tiny neighborhood of 19th-century brick warehouses against the invading forces of New York real estate. "Tourists don't like the smell of the fish market," he said. "Wall Street traders tend to want newer buildings with more amenities. So what you have is a close, tight little community of people who are drawn to this." He paused. The Fulton Fish Market, which has been in operation since 1822, is moving to the Bronx, probably before the end of next year. "It's the end of a history," said Nicole Bilu Brier, who lives with her husband, Greg Brier, and their 4-month-old son, Flynn, in a converted icehouse on Front Street. An ancient iron safe, too heavy to move, occupies one corner of their floor-through loft; they use it as a liquor cabinet. The market's aroma was no comfort when she was pregnant, Ms. Brier said, but it keeps the rents down. "We like the seediness of the neighborhood," she said. "There's fewer and fewer places like this." To the untrained nose, the air carried notes of Atlantic coastal breeze, deep-water seafood and F.D.R. Drive exhaust. In a pocket community distinguished by its resistance to change, the market's departure is just one shoe dropping. In June the city sold a strip of 11 abandoned buildings and vacant space to a developer for $5 million, to be turned into 96 rental apartments and retail space. After renovation, the 11 buildings will retain their low-slung 19th-century exteriors. The fish market site is part of a city-owned stretch of waterfront being considered for redevelopment, extending from the Whitehall Ferry Terminal to Pier 40 at the foot of Houston Street, according to Janel Patterson, a spokeswoman for the New York City Economic Development Corporation. Plans for the two fish market buildings, one with landmark status, are not yet settled, Ms. Patterson said. Private fish companies are also expected to vacate a number of commercial buildings across South Street. The 38 acres that the New York City Landmarks Commission designated as the South Street Seaport Historic District in 1977 make up one of the oldest neighborhoods in New York, and at the right hour one of the most robust. The district, which includes the fish market, hugs the waterfront from John Street to Dover Street, anchored at the foot of Fulton Street by a mall of restaurants and stores. At last unofficial count the district had 200 to 250 residents, clustered in 15 or 20 buildings on 11 very unsquare blocks. Many residents are involved in the arts. By day the streets are almost empty. But by night, in the hours of the fisherman's breakfast — a delicate repast of eggs, hash browns, bacon, kippers, toast and whiskey — armies of union workers stack 200-pound groupers along busy slips and salt the night air with baroque cursing that would make you believe the fish still come and go on ships. (Now trucks do the job.) On the uneven stone streets, these reefer trucks make a racket that could suck the sleep from the dead. Mr. Brier, who owns a SoHo lounge called Groovejet, said he likes going home in the middle of the night to a neighborhood in full motion. "What you see between 1 a.m. and 7 a.m. is absolutely amazing," he said. "There'll be fires in the trash and a guy with a gaff hook in a seven-foot swordfish. The integrity of the neighborhood is funky and cool. We don't want it to get too cleaned up." The inconveniences of the neighborhood, he said, "we hope will keep away the people we don't like." The Briers said that when they moved from Chelsea last year, they were promised rent subsidies under a federal program to attract residents to Lower Manhattan after the Sept. 11 attacks. Mr. Brier said they had not seen any money yet, but were enjoying other advantages of the neighborhood. Since the move, he has photographed the Brooklyn Bridge every day. "You really feel part of the water here," he said. IN these transitional weeks between late summer and early fall, the streets feel languorously cut off from the bustle of the financial district or the tourist activity of the harbor and the mall. The scale is small, the action slow. The handmade brick on the buildings turns a soft pink in the afternoon light. At dusk, from the outdoor tables at Quartino, a Ligurian restaurant that opened on Peck Slip in 2000, the tall buildings of the financial district rise over the neighborhood like the illuminated screen of a drive-in movie. Painted signs peeling from warehouse facades announce businesses long forgotten. Above a Beekman Street coffee shop called Pepper Jones, a sign for Meyer's Brand advertises fresh, salt and something-ed fish. The shop's owners recently announced plans to leave the city. ("A disaster," said one neighbor. "It's the neighborhood living room," said another.) The owners bought the building in 1997 for $450,000; after a $582,000 renovation, they said they hope to sell it for $2.25 million. The people in the district have for 20 years fought a developer's plans to build a residential tower of up to 43 stories in the district; in April, the City Council rezoned the area to prohibit buildings over 120 feet. Though some, like Mr. Fagin, welcome the prospect of new neighbors in the renovated buildings, they fear that the fish market, now the most distinctive element of the neighborhood, will be replaced by generic stores like those on Fulton Street — or worse, a giant hotel that would block their views of the river. Richard Sack, an independent real estate agent whose office is on Front Street, said that the few co-ops or condominiums in the neighborhood sell for $700,000 to $1.8 million; rental apartments bring about $2,000 for a small loft to $6,000 for a large one. With the fish market leaving, he said, new residents and businesses are eager to buy in. He said he hoped the retail development coming to his block would not follow the mall on Fulton Street, whose stores, including J. Crew and Brookstone, might be anywhere. "How high do rents have to go before the only people who can afford it are Häagen-Dazs?" he asked. Rob Barocci, a cinematographer who lives in a rented loft on Water Street with his wife, Angie Day, a novelist, said he is already feeling a pre-emptive "nostalgic sense of loss" for the fish market. The loft bears subtle reminders of its warehouse roots, including steel pillars covered in red bricks. Most of the neighbors are artists or architects. The market, Mr. Barocci said, was part of what attracted him to the neighborhood. "I had an office in the meatpacking district, and that connection to old New York is already gone," he said. "What I love about the fish market is that it's one of the last vestiges of New York as a working city." Like the autumn light, the gauze of memory and historic preservation can play tricks among these weathered streets. As is often the case, historic preservation here feels like a seductive oxymoron. The movement of history — of boom and decay, not to mention organized crime — is precisely what advocates would like to preserve the neighborhood from, as if history were a moment and not a sweep of motion. For many in the seaport, historic preservation blurs with autobiography: you worry over the old buildings not to preserve the past, but to preserve the present, before the unknown arrives — or more precisely, to preserve the present's relationship to the past. It is the present, after all, that is slipping away. Yet history is nothing if not the process of change, and change is nothing without the force of rot. For much of its two centuries plus, the history of the seaport community has been one of cyclical decline and, in downtimes, abandonment. In his classic 1952 New Yorker article about the seaport, "Up in the Old Hotel," Joseph Mitchell quoted the owner of Sloppy Louie's restaurant, formerly on Front Street, about the building's past. "The Fulton Ferry Hotel lasted 45 years," said the restaurateur, Louis Morino, "but it only had about 20 good years; the rest was downhill." (At the risk of giving myself away, I know how the hotel feels.) For Mitchell, as for the neighborhood, this was not an aberration but the rhythm of port history: one day you're grand, the next you're a flophouse for low characters. In a loft building on Front Street, opposite the strip of buildings being renovated, Kit White, 52, remembered a more complicated past. When he moved to the neighborhood in 1974, following the lead of the artists Robert Indiana and Mark di Suvero, the landmarks commission had only recently spared it from demolition by the developer Atlas-McGrath. Most of the buildings were shuttered and rotting from the inside. With another artist, he bought one of those wrecks in 1977 for $45,000. The wise guys who played cards across the street assumed that Mr. White and his partner were a police surveillance team until they saw how hard the artists labored at renovation, Mr. White said. Though friends thought he had left civilization, he said, before the United States Attorney's office cracked down on organized crime in the market in the early 1980's the neighborhood had no street crime. Sea gulls clamored around fish carcasses in the mornings; he collected the shells of clams they dropped on his terrace. There was only one cigarette machine in the neighborhood, so the artists, fishmongers and wise guys all lived in each other's orbits. "New York just gets more and more sanitized," he said. "Things are more convenient, but it takes away a lot of the grit and the sensory experience." With his wife, Andrea Barnet, a writer, he found the neighborhood ideal for raising their daughter, Pippa, now 17. "It's like a small town, and the rest of Manhattan doesn't exist," he said. Halloween remains the highlight of the year, he said, because you can see everybody in the neighborhood and visit every home. Pippa was one of a handful of babies who were born in the neighborhood within a few months of each other and who grew up together. "I think I learned about the neighborhood most from Halloween," she said. Father and daughter are both taking the loss of Pepper Jones like a tragedy in the family. "I have been fighting for 25 years to save buildings in the neighborhood," Mr. White said, including the 11 buildings recently sold for development. "I have more than a little ambivalence now, because I know it will change the neighborhood." "I don't know what it's going to feel like," he added. "Maybe the character will remain intact, and it will continue to attract the kind of person drawn to it now." IN Mitchell's "Up in the Old Hotel," the owner of Sloppy Louie's enlists the writer to take an old elevator up to explore the Fulton Ferry Hotel, which has been sealed up for as long as the restaurant has been downstairs. After a few dusty minutes Louie has seen enough. "Sin, death, dust, old empty rooms, old empty whiskey bottles, old empty bureau drawers," he says. "Come on, pull the rope faster! Pull it faster! Let's get out of this." The nostalgia of old places is comforting because it conjures a time without surprises. But real engagement with the past, as Sloppy Louie realizes, can be a fright. Under the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge, Mr. Fagin unlocked a small lot that the neighborhood had reclaimed as a community garden. He said he was not afraid of gentrification but rather "the quaintification of history." The Brooklyn Bridge, which opened to traffic in 1883, first signaled the doom of the old Fulton Ferry Hotel, which lost its saloon trade as people no longer needed the ferries to get across the river. As for Sloppy Louie's, it is now an outpost of the Heartland Brewery chain, its business tied to the spotty rhythms of the tourist trade. A paradox of the seaport area is that it lacks a good seafood restaurant. Mr. White said he did not know what he wanted to happen in the market's place. This time the residents are not fighting a developer or a zoning law. "We're all just in mourning," he said. "There isn't much room for fighting this."  Jack from Monte's Seafood at the Fulton Fish Market shovels ice while waiting for customers at 3 a.m. Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company

April 3, 2004

ABOUT NEW YORK That Smell? Fish and Sweat, Fading Into a Sanitized Future By DAN BARRY THE mounds of tuna piled upon the cobblestones. The fire barrels aglow upon the piers. The wooden hand carts, bearing the carved names of their owners. The pavement, wet, always wet. And the men: loaders and unloaders, wholesalers and salesmen, wise guys and tough guys, journeymen and family men. More than 20 years ago, a slight young woman named Barbara Mensch ventured one block east from her Water Street apartment, into the testosterone-charged air of the Fulton Fish Market. Knowing that the city and developers had this ancient stretch of South Street squarely in their sights, she packed her Rolleiflex camera and her tape recorder, and set out to capture a way of life that had been marked to die. Night after night, in the gloom beneath the Franklin D. Roosevelt Drive, she chronicled what she could, from the face of Vinnie the Bone - a fillet man - to the syntax of a closed world ("Livin' down in the fish market has always been a beautiful thing to my opinion."). Finally, in 1985, she published a book of photographs and oral history with an appropriately wistful title: "The Last Waterfront." Ms. Mensch moved on to other projects - including marriage, childbirth, and divorce - but she never moved away. She still lives on the top floor of that old sausage factory on Water Street. She still breathes in the Melvillian air. And she still bears witness to the gradual crushing of Manhattan's fishmonger culture. The city has long maintained that the South Street operation is so antiquated that New York might one day lose its wholesale seafood industry. That is why the market will move within the year to Hunts Point in the Bronx - a world in its own right, but not South Street. Meanwhile, developers continue to convert the neighborhood's old buildings into luxury residences for people rich enough to afford a dockworker's strut. And consultants for the city continue to sketch out a new waterfront. Of course, they will have to work around the market's Tin Building, a landmark that has been there, in one form or another, since forever. Ms. Mensch, 51 now, walked through the neighborhood the other day, pointing out what was, and what is. Here was a smokehouse; now a residence. Here was Mr. Blumenfeld's rag business; now a residence. Here was Sloppy Louie's, a classic waterfront dive; now a wholesome brewpub. Here, on the corner of South Street and Peck Slip, was the rough-and-tumble Paris bar, with Meyer's Hotel upstairs. The first night of her fish market expedition, a scar-faced man cursed her out the door, but not before Mike the bartender whispered that she should come back in the morning. He understood the need to capture what was slipping away. The Paris, long since cleansed of its grappling-hook ambience, caters now to tourists and college students. And Mike, long since gone, remains vivid in one of Ms. Mensch's photographs, cigarette in hand, staring into the distance as if reading the future. The photographer brooded as she walked. "Now I look at this place, and it's like death to me," she said. "There's nothing living." Ms. Mensch knows that she is not exactly Molly Malone; she grew up in Brooklyn, attended Hunter College and works as an artist. She also knows that she can sound as though she is waxing nostalgic for good old days that were not always so good. Should we yearn for the days of mob control? Of violence? Of men on the docks saying the foulest things imaginable to a young woman with a camera? No, of course not, she said. And, yes, of course, change is inevitable. WHAT bothers her is this encroaching homogenization, this gradual separation of the city's present from its past - as if Vinnie the Bone were carving bone from meat. South Street and its fish market evoke the earliest days of Manhattan Island: open-air stalls; a commerce based on halibut and shrimp, crabs and blues; and the salt-scented air uniting city dwellers with the open water. "Everything is discarded; nothing has value," Ms. Mensch continued. "And what is put in its place? It's what we're replacing these things with that bothers me." As she spoke, the uniqueness of this "historic district" in Lower Manhattan seemed to melt away, like ice chips falling on fish market pavement. Suddenly, the South Street Seaport became indistinguishable from Faneuil Hall in Boston, the Inner Harbor in Baltimore, the rest of it. Novelties on cobblestones, nothing more. Ms. Mensch is planning a second book, a kind of sequel, tentatively called "A South Street Story." She plans to be there, camera in hand, when the last fish flops. Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company Fulton Market Looks Forward to

Bronx Dawns

|

|||||||||||||

|

links |

http://www.beyerblinderbelle.com/subframes/projects/ss_seaport_exhibit.html | ||||||||||||