|

New York

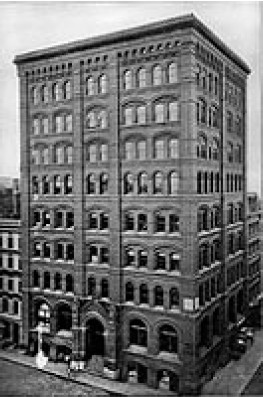

Architecture Images-Seaport and Civic Center Morse Building |

|

architect |

Silliman & Farnsworth |

|

location |

12 Beekman St. |

|

date |

1880 |

|

style |

Rundbogenstil (German round-arched neo-Romanesque) |

|

construction |

brick |

|

type |

Office Building |

|

|

|

|

images |

|

|

|

|

|

notes |

The 10-story Morse Building is one of New York's earliest surviving high-rise office buildings and was one of the first ‘modern’ tall buildings. It was built as a speculative venture by the nephews of Samuel F.B. Morse, whose early experiments with the telegraph were conducted on this site. The flat roofline gives the building a simple box-like appearance that subsequent designers of high-rises worked hard to avoid. The building was a pioneer in its use of a nearly all brick façade, which also served the purpose, along with the wrought iron floor beams, of fireproofing the building. This red and black brick façade is articulated with fluted piers defining the central bay and corners. The almost industrial logic of its original architecture was lost when the basement and ground floors were refaced in 1902 and an additional 2-stories increased its height to 12-stories. |

|

Photo: 1999 Landmarks Preservation Commission September 19, 2006, Designation List 380 LP-2191 MORSE BUILDING (later NASSAU-BEEKMAN BUILDING), 138-142 Nassau Street (aka 10-14 Beekman Street), Manhattan. Built 1878-80, [Benjamin, Jr.] Silliman & [James M.] Farnsworth, architects; Addition 1901-02, [William P.] Bannister & [Richard M.] Schell, architects. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 100, Lot 26. On March 14, 2006, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Morse Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Two speakers, one of them a representative of the Historic Districts Council, spoke in favor of designation. In addition, the Commission has received a resolution from Manhattan Community Board 1 and communications from the owner, 140 Nassau Residence Corp., and Councilmember Alan J. Gerson in support of designation. Summary The current form of the Morse Building results from three periods of construction: the original (1878-80), as well as alterations in 1901-02 and c. 1965. Today, the structure’s 6-story midsection, with two articulated facades featuring round- and segmental-arched fenestration, is, in part, the earliest surviving (as well as one of the very few surviving) tall “fireproof” New York office building of the period prior to the full development of the skyscraper. The original 8-story (plus raised basement and attic) Morse Building was a speculative commission by Sidney E. Morse and G. Livingston Morse, cousins who were sons of the founders of the religious newspaper The New-York Observer, and nephews of Samuel F.B. Morse, the artist and inventor of the electric telegraph. The first major New York design of architects [Benjamin, Jr.] Silliman & [James M.] Farnsworth, employing a generally-praised stylistic combination of Victorian Gothic, neo- Grec, and Rundbogenstil, the building was located in the center of the city’s newspaper publishing and printing industries, as Park Row and Nassau Street were redeveloped with significant tall office buildings. It is an early example of the use of brick and terra cotta for the exterior cladding of office buildings in that period. The intricate polychrome brickwork, among the finest of its time surviving in New York City, was supplied by the Peerless Brick Co. of Philadelphia. It features hues of deep red contrasted with glazed black, the latter employed ornamentally, largely to emphasize the outlines of the fenestration. Terra cotta manufactured by the Boston Terra Cotta Co., one of the first East Coast firms, was used for details such as sillcourses and rondels. Just 20 years after its completion, the Morse Building was considered small and old-fashioned compared to very tall 1890s steel-framed skyscrapers. The Nassau-Beekman Building, as it was re-named, was altered in 1901-02 to the “Edwardian” neo-Classical style design of architects [William P.] Bannister & [Richard M.] Schell. This entailed remodeling the base; reconstructing the upper two stories, capped by a projecting balcony/cornice supported by enormous scroll brackets; and adding four steel-framed stories clad in creamcolored brick, bringing it to 14 stories. The shift in color and style of this alteration apparently reflected the influence of the recently-built Broadway Chambers Building (1899-1900, Cass Gilbert). From 1919 to 1942, the former Morse Building was headquarters of the United Cities Realty Corp. The base of the structure was altered again c. 1965, and the 10th-story balcony/cornice was removed. The building was converted from office to residential use in 1980. 2 DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Morse Family and the Morse Building 1 The Morse Building was commissioned by Sidney Edwards Morse (1835-1908) and Gilbert Livingston Morse (1842-1891), cousins who were nephews of Samuel Finley Breese Morse (1791-1872), the artist and inventor of the electric telegraph (first operated in 1844). Sidney was the son of Richard Cary Morse (1795-1868), while G. Livingston was the son of Sidney Edwards Morse (1794-1871). The two elder Morses were the founders (1823) and publishers (until 1858) of The New-York Observer, called “the oldest existing religious newspaper in the United States” in King’s Handbook.2 G. Livingston Morse, born in New York City, was the inventor (c. 1869), with his father, of the bathometer, an instrument used in the exploration of sea depths, and was a partner and officer (1879-86) in the Nickel Alloy Co. (later Holmes-Wessell Metal Co.). He also served as a vice-president of the Mortgage Investment Co. (later Eno-Bunnell Investment Co.), as well as an alderman, acting Mayor, police commissioner, and Board of Education member in Yonkers. Sidney E. Morse was listed in the 1878-79 city directory as a pickle merchant. After the completion of the Morse Building, Sidney E. Morse & Co., pedometers, was located here until 1884, with both cousins associated with the firm. Afterwards, until G. Livingston’s death, their firm was S.E. & G.L. Morse, variously listed as bankers, brokers, real estate, and loans. The site of the Morse Building, at the northeast corner of Nassau and Beekman Streets, was the location where The New-York Observer was published from 1840 to 1859. Sidney E. [elder] and Richard C. Morse had an ownership interest in this property by 1845. Their executors conveyed the property to Sidney E. [younger] and G. Livingston Morse in June 1878. That month, the New York Times carried the following item: The old building at Nassau-street and Beekman long and unfortunately known as the Park Hotel has just been demolished, and on its site will rise one of the one of the finest buildings in the lower part of the City. The property is part of the Morse estate, and the new building, which is to be built by S.E. & G.L. Morse, will be called the Morse Building. 3 Architects Silliman & Farnsworth filed for the construction of the speculative office building, to be eight stories (plus a raised basement and an attic). Construction began in June 1878 and was completed in March 1880. “Current work” listings in The American Architect & Building News indicated that the project cost $200,000.4 The Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide referred to it as “the immense pile of masonry far overtopping adjoining structures, which has attracted the attention of thousands of pedestrians along Broadway.”5 With frontages of 85 feet on Nassau Street and 69 feet on Beekman Street, the structure was then “considered absolutely fire-proof”6 Architectural historian Sarah B. Landau and engineering historian Carl Condit described the Morse Building’s construction: It had unusually thick, brick bearing walls, 4 feet at the cellar level and 3.5 feet at the first floor. The roof was iron beamed, and the floors were constructed with 15-1/4-inch wrought-iron beams that were spanned with corrugated iron arches and filled in with concrete according to Hoyt’s patent fireproof construction to produce a curbed ceiling that was finished in flat, glazed tile. As additional protection, all partitions were covered with iron laths and plaster by Smith & Prodgers, who were the mason builders as well as the plasterers. This firm had worked on the Equitable and Western Union buildings and was one of the best in the business. It was in the construction of the Morse that the iron contractor Post & McCord used steampowered derricks to hoist iron beams and girders for the first time. 7 Upon its completion, the owners claimed that the Morse Building was “the tallest straight wall building in the world.”8 Interior amenities included some 175 offices, two hydraulic Otis elevators, steam heat, gas lighting, and fireplaces. A New York Times advertisement in March 1880 offered for rent “a large first-floor room, suitable for an institution.”9 The Morse Building was among the first of the major downtown office buildings to be erected after recovery began from the financial Panic of 1873. Several notices after completion of the building indicated the shrewdness of this investment, as the nature of office buildings and the demand for space downtown changed. In December 1881, the Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide commented that the demand for offices is no longer confined to the neighborhood of the Stock, Mining, Cotton and Produce Exchanges. All the great industries which are represented in New York are using offices instead of stores, and these last are very profitable. Eugene Kelly paid $250,000 for the lots on the corner of Nassau and Beekman streets. The building he erected [Temple Court] is a very costly one, yet it is said it will net him a profit of 20 per cent, per annum.10 This was followed in February 1882 by the statement that 3 in no part of the city has there been so great an increase in rents as in the great business centres, especially in the lower part of the island. . . The demand for well-located offices in Broad, Pine, Cedar, Wall and New streets, Exchange place and Broadway below Fulton street, is not only keeping pace, but fast outrunning the accommodations which have been provided, or which are nearing completion. Already many of the offices in the Marquand, Kelly, Mills, and Tribune structures are engaged, and at very fair figures.11 And in May 1882 was the further comment that “the Tribune, Times, Morse buildings and Temple Court are nearer the law courts, and better for lawyers and public offices.”12 The Morses claimed in 1883 to be receiving ten percent on their initial investment.13 The Tall Office Building in New York City in the 1870s-80s During the 19th century, commercial buildings in New York City developed from 4-story structures modeled on Italian Renaissance palazzi to much taller skyscrapers. Made possible by technological advances, tall buildings challenged designers to fashion an appropriate architectural expression. Between 1870 and 1890, 9- and 10-story buildings transformed the streetscapes of lower Manhattan between Bowling Green and City Hall. During the building boom following the Civil War, building envelopes continued to be articulated largely according to traditional palazzo compositions, with mansarded and towered roof profiles. The period of the late 1870s and 1880s was one of stylistic experimentation in which commercial and office buildings in New York incorporated diverse influences, such as the Queen Anne, Victorian Gothic, Romanesque, and neo-Grec styles, French rationalism, and the German Rundbogenstil, under the leadership of such architects as Richard M. Hunt and George B. Post. New York’s tallest buildings – including the 7-1/2-story Equitable Life Assurance Co. Building (1868-70, Gilman & Kendall and George B. Post) at Broadway and Cedar Street, the 10-story Western Union Building (1872-75, George B. Post) at Broadway and Liberty Street, and the 10-story Tribune Building (1873-75, Richard M. Hunt), at 154 Nassau Street – all now demolished – incorporated passenger elevators, iron floor beams, and fireproof building materials. Fireproofing was of paramount concern as office buildings grew taller, and by 1881-82 systems had been devised to “completely fireproof” them.14 The Morse Building utilized the successful design, construction, fireproofing, and planning techniques of these earlier buildings. “Newspaper Row”: Park Row and Nassau Street 15 The vicinity of Park Row, Nassau Street, and Printing House Square, roughly from the Brooklyn Bridge to Ann Street, was the center of newspaper publishing in New York City from the 1840s through the 1920s, while Beekman Street became the center of the downtown printing industry.16 Beginning in the 1870s, this area was redeveloped with tall office buildings, most associated with the newspapers, and Park Row (with its advantageous frontage across from City Hall Park and the U.S. Post Office, as well as its proximity to the Brooklyn Bridge) and adjacent Nassau Street acquired a group of important late-19th-century structures: Tribune Building (1873-75; demolished); Morse Building (1878-80; 1901-02); Temple Court Building and Annex (1881-83, Silliman & Farnsworth; 1889-90, James M. Farnsworth), 3-9 Beekman Street; Potter Building (1883-86, N.G. Starkweather), 38 Park Row; New York Times Building (1888-89, George B. Post; 1903-05, Robert Maynicke), 41 Park Row; World (Pulitzer) Building (1889-90, George B. Post; demolished), 53-63 Park Row; American Tract Society Building (1894-95, R.H. Robertson), 150 Nassau Street; and Park Row Building (1896-99, R.H. Robertson), 15 Park Row.17 The Architects 18 The firm of Silliman & Farnsworth, architects of the Morse Building, existed from 1876 to 1882. James Mace Farnsworth (1847-1917), born in New York City, apparently began his career around 1872 and worked as a draftsman with the noted architect Calvert Vaux by 1873. Benjamin Silliman, Jr. (1848-1901), born in Louisville, Ky., was the third generation in his direct family line with the same name. His grandfather (1779-1864), considered “the most prominent and influential scientific man in America during the first half of the nineteenth century,”19 had been a professor of chemistry and natural history at Yale University (1802-53). Samuel F.B. Morse had acquired his interest in electricity while studying under Professor Silliman. Silliman’s father (1816-1885) was also a noted professor of chemistry at Yale. Silliman, Jr., graduated from Yale University in 1870, studied architecture for three years in Charlottenburg [Berlin], Germany, and upon his return to the U.S. worked for the firm of Vaux, Withers & Co., where he met Farnsworth. Silliman & Farnsworth obtained a number of prominent office and institutional building commissions, for which they produced designs influenced by the Rundbogenstil and the neo-Grec and Queen Anne styles, most executed in red brick and terra cotta. Their Morse Building (1878- 4 80), the location of their office, was called “the first work of any prominence they have placed before the building trade of New York, and a work of which they may well be proud” by the Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide.20 The firm also designed the Vassar Brothers Laboratory (1879-80; demolished), Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, N.Y.; the Orange Music Hall (1880; demolished), Orange, N.J.; a hospital (1880; demolished) at Lexington Avenue and East 52nd Street; two commercial buildings at Nos. 19 and 21 East 17th Street (1881-82);21 and the Temple Court Building (1881-83). Farnsworth practiced independently from 1883 to 1897, producing numerous designs for commercial and office buildings and warehouses for prominent builder-developer John Pettit, including additions to the cast-iron Bennett Building22 in 1890-94. He was responsible for the Singer Building (1886), Pittsburgh, Pa., and designed the Temple Court Annex (1889-90); he maintained his office in Temple Court in 1890-92. Associated with a number of other architects over the years, he worked with Charles E. Miller from 1897 to 1900, then with [J.A. Henry] Flemer & [V. Hugo] Koehler in 1900-01, and as part of Koehler & Farnsworth c. 1903-10; he practiced alone until his death. Little is known of Silliman’s subsequent practice, though he remained listed in New York City directories until around 1900. He moved to Yonkers around 1883, and former colleague George Martin Huss reminisced after Silliman’s death that “I believe that [he] built largely in Yonkers.”23 He was living in Harlem at the end of his life. The Design of the Morse Building 24 The design of the Morse Building reflects the shift from the palazzo model for office buildings begun in the 1870s by Richard M. Hunt with the Tribune Building, among others. Stylistically, the building displays a combination of influences, including the Victorian Gothic and neo-Grec, along with the Rundbogenstil. The Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide in 1879 called it “a distinctly modern style, an adaptation of the Romanesque and Gothic combined, still with well-curved Roman arches.”25 Sarah B. Landau has discerned the direct influence of the Evening Post Building (1874-75, architect undetermined; demolished) and Hunt’s Tribune Building. The polychrome Morse Building was also one of the early tall New York office buildings of the 1870s that employed brick and terra-cotta cladding. The corner location allows for two full facades, each of which is articulated vertically by monumental pilasters (which reflect internal party walls), dividing the facades into three sections on Nassau Street and two sections on Beekman Street. The building was originally arranged horizontally into four sections: a base, consisting of a raised basement and main first story; two similar midsections articulated by one story of round-arched fenestration surmounted by two stories with paired segmental-arched fenestration; and an upper section with one story of round-arched fenestration and an attic story with patterned brick corbelling and arches, terminated by a molded cornice with ornamental terra-cotta parapet. The walls were further elaborated by patterning, corbelling, stringcourses, rondels, and moldings. The original Nassau Street entrance had an elaborately ornamented round-arched surround of brick and terra cotta, with stairs leading to the first story. Landau and Condit opined that the “relative simplicity and regularity of the facade treatment imparted a quality of wholeness not typical of early skyscrapers.”26 The Morse Building provides an interesting contrast with the slightly later Temple Court Building, by the same architects, and the Potter Building, all three executed in red brick and terra cotta, at the same intersection of streets. Despite the decidedly mixed contemporary comment on most prominent tall buildings of the late-19th century in New York, the Morse Building was generally praised. A critic in The American Architect & Building News in January 1879 wrote that The architects had the difficult problem to solve, in designing the exterior, of a large, many-storied building, placed on the corner of two relatively narrow streets, and it seems questionable whether they have been altogether successful. ... the effect produced [of the base] is excellent, and shows perhaps the best use of brick of any work in the city, and is certainly a very creditable composition, both in its proportions and its color; above this, however, the design seems to hesitate between two different modes of treatment [round- and segmental-arched windows], not accepting either mode frankly enough to be successful... The effect of the building is excellent, however, and the construction seems to have been carefully studied and well carried out; it certainly is a relief to find work challenging criticism by its good points rather than by its bad ones. 27 The same publication in July 1879 found that “there is contrast, diversity, and change, a great remove from monotony and a solution of the difficult problem which must strike all as a most satisfactory one.”28 The Manufacturer & Builder in 1879 considered it decidedly agreeable in its general appearance as well as in its details. The cause of this is the fine form of the many windows and the judicious use of black and molded bricks in the walls, while the effect of the 5 whole is harmonious and chaste. The only criticism made by some is that the roof is flat, or rather that no roof is visible. 29 (Critic Montgomery Schuyler was one of those who thought that a steep roof made a building an “impressive object” in the lower Manhattan skyline).30 Renderings of the Nassau Street facade and the main entrance were featured in Carpentry & Building in 1879 and The American Architect & Building News in 1880.31 The English The Building News in 1883 referred to it as “a very quiet and pleasing structure, well proportioned, and not at all glaring or showy.”32 Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer in The Century in 1884 wrote “nor is the Morse building without evidence of effort in the right direction”33 in the design of office buildings. King’s Handbook in 1892 called it “a striking illustration of the architectural beauty of brick and terra cotta. It is a solid handsome structure...”34 In Silliman’s obituary in The American Architect & Building News in 1901, the Morse Building was called “one of the first and most successful of the many-storied office-buildings.”35 And Schuyler, considering the base of the building again in 1902, named it one of the last and one of the best works of the Gothic revival in New York, of that true Gothic revival which consisted not in the reproduction of Gothic forms, but in the application of the Gothic principle of functional expression. 36 Today, the Morse Building is the earliest surviving (as well as one of the very few surviving) tall “fireproof” New York office building of the mid-1870s to mid-1880s, the period prior to the full development of the skyscraper.37 Its significance is enhanced by its visibility on a corner with two articulated facades, and its location within the district near City Hall Park that was developed with tall office buildings beginning in the 1870s. The Morse Building, Brick, and Architectural Terra Cotta in New York City 38 The polychrome Morse Building is an early example of the use of brick and terra cotta for the exterior cladding of tall office buildings in the 1870s-80s, a trend seen in such brick structures as the Boreel, Western Union, and Tribune Buildings. As observed in 1881 by Montgomery Schuyler: The architects of the present generation found commercial New York an imitation of marble, either in cast-iron or in an actual veneer of white limestone. They are likely to leave it brick. . . Whatever of interest has since been done in business buildings has been done in baked clay, more and more including the use of terra-cotta as well as of brick. The first of the noteworthy attempts to build in brick alone . . . was Messrs. Silliman and Farnsworth’s Morse Building, which remains one of the most interesting and successful of these attempts. The manufacture of terra-cotta has been much improved in the interval, but there has been no example of brickwork built since in which moulded brick and colored brick have been used with more fitness and sobriety, nor in which a more agreeable and satisfactory result has been attained. 39 The intricate brickwork of the Morse Building features brick that was manufactured in a wide variety of ornamental shapes, both cut and molded, in hues of deep red and glazed black. The black brick was employed ornamentally, largely to emphasize the outlines of the fenestration. The Peerless Brick Co. of Philadelphia, a leading producer in this period of quality pressed bricks, supplied the brick for the building.40 Peerless had been a pioneer in the improvement of brick-making machines that successfully increased the efficiency and quality of their manufacture. By 1880, the company advertised ARCHITECTURAL SHAPES 300 kinds. Also RED Pressed Fronts. Extra fine in color and quality. ... [and] BLACK, Velvety jet face. The only black brick fit for a fine building, producing a beautiful effect, and free from the glossy and greasy look of other black or dipped bricks. DIAPERING and ORNAMENTAL Bricks made in the above colors. 41 The American Architect & Building News commented that The Peerless Company has revolutionized the manufacture of bricks, and has gone far toward effecting a welcome revolution in brick architecture, not alone by the infinite variety of shapes and excellence of finish which the company imparts to the bricks it turns out, but also by the reason of the beauty of their color. 42 While a number of architects had attempted in the 1850s to employ architectural ornament of terra cotta in New York,43 it was after the Chicago and Boston fires of 1871-72 that terra cotta was revived as a significant interior and exterior building material in the United States. Walter Geer later noted that “by these fires it was 6 conclusively demonstrated that fire-proof buildings could not be made of unprotected stone or iron, and that only brick and terra-cotta walls were practically fire-proof. This increased use of brick work, and of terra-cotta as a constructive and decorative material in connection with brick work, revived the demand for the manufacture of this material in or near New York.”44 (The term “constructive” in this quote refers to the manner in which the terra cotta was fully integrated into the exterior brick bearing walls). In the 1870s and early 1880s, architectural terra cotta was often a color that matched stone (commonly brownstone, buff or red) that could be employed in pleasant juxtaposition with brick, or as a substitute for brownstone. The Record & Guide remarked that during this period “terra cotta is most generally used for the trimming and ornamentation of buildings, taking the form of panels, courses, friezes, small tiles, roofing tiles and paving blocks.”45 George B. Post was a leader during this period in New York City in the use of exterior terra cotta, in his designs for the Long Island Historical Society (1878-81),46 New York Produce Exchange (1881-84; demolished), and Mills Building (1881-83; demolished). Among other contemporary architects who employed terra cotta were Kimball & Wisedell, designers of the Casino Theater (1881-82; demolished), an early New York building having highly intricate, exotic terra-cotta ornament, and Silliman & Farnsworth. The Morse Building, with terra cotta by the Boston Terra Cotta Co.,47 one of the first terra cotta firms on the East Coast, was then considered the first prominent New York office building to employ exterior terra cotta, though it was used relatively sparingly for architectural details, such as sills, sillcourses, entrance surround elements, foliate rondels, and cornice. The Morse Building was constructed early enough in the revival of the use of terra cotta in New York that The American Architect & Building News expressed There are matters of pure construction which are as yet unsettled: terra-cotta is used in various ways as constructive ornament, and it remains to be seen whether a satisfactory exhibit of the employment of that material is to be given us in this city. No one will claim that any terra-cotta work of consequence has yet been done here. The Morse Building will be interesting as an experiment, and as such much of its terracotta work must be classed. 48 James Taylor, “the father of American terra cotta,” later credited Silliman & Farnsworth with one technical innovation in their employment of terra cotta on the Morse Building: “In this building the raised or protected vertical joint was first used. This form of joint prevents the rain from scouring out the pointing mortar, and it is an important and necessary precaution which ought to be used upon all exposed surfaces.”49 The Morse Building was an early and significant building to employ exterior architectural terra cotta in its second American phase, and is today a rare surviving example of a tall New York office building of its era employing exterior (polychrome) brick and terra cotta. The brickwork is among the finest of its period surviving in New York City. Nassau-Beekman Building 50 The base of the Morse Building was damaged in the disastrous fire in January 1882 that destroyed the World Building at Park Row and Beekman Street. According to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle: The handsome front of the Morse Building is much injured. The brick and terra cotta works of the lower story and the window frames were smashed, and the area lights broken in. The building to-day looks rather dilapidated, as a consequence. Mr. Morse characterized the action of the firemen in allowing the wall to fall on his building as a piece of downright vandalism. 51 Following the death of G. Livingston Morse in 1891, Sidney E. Morse, the building’s co-owner and his cousin’s executor, sold a half-interest in the property in May 1892 to Nathaniel Niles, a New York lawyer who resided in Madison, N.J., and acquired it as an investment. Morse conveyed the other half-interest to Niles in February 1895, but maintained a real estate office here until his death in 1908. King’s Handbook in 1892 indicated that “the offices are occupied for the most part by lawyers and the agents of manufacturing corporations. ... Seldom are any of its offices vacant.”52 For several years, from about 1896 to 1900, the Morse Building was the site of the office and rooftop studio of one of the earliest American motion picture companies, which became the American Vitagraph Co., founded by James Stuart Blackton and Albert Edward Smith. Smith later reminisced that “the top floor of the Morse Building... was a cut-rate haven occupied largely by poverty-stricken newspaper artists and cartoonists.” “Burglar on the Roof,” filmed here, was the studio’s “first posed picture” in May 1897.53 In August 1898, the New York Times disclosed that the Washington Life Insurance Co. had instituted foreclosure proceedings against Niles and his partners for failure to pay the mortgage. The property, offered at auction in March-April 1899, was acquired by the insurance firm for $601,000. A deal was arranged by Washington Life in November 1900 where the company traded the Morse Building in exchange for the Hamilton 7 Storage Warehouse building, at the northeast corner of Park Avenue and 125th Street, owned by Charles Ward Hall. The Times reported that “the Morse Building will be remodeled, in fact almost reconstructed, to make it conform as nearly as possible to the requirements of a modern office structure.”54 Just 20 years after its completion, the Morse Building was considered small and old-fashioned, particularly when compared to modern, very tall steel-framed skyscrapers, such as the 20-story (plus 3-story tower) American Tract Society Building (1894-95) next door. Architects Bannister & Schell filed in December 1900 for the alteration of the Morse Building in an “Edwardian” neo-Classical style, which was expected to cost $150,000. This entailed remodeling the two-story base (the former basement and first story levels were rearranged as two full stories) with a heavily rusticated treatment, having a pedimented entrance with columns; reconstructing the former 8th and attic stories; and the addition of four steel-framed stories, bringing the structure to 14 stories. The firm of Bannister & Schell was established c. 1899 and apparently lasted until the 1930s, despite the death of one of the partners. William P. Bannister (c. 1869-1939), born in New York City, worked in the offices of a number of New York architects, and established an independent architectural practice by 1886. He was joined in partnership by Richard Montgomery Schell, who died in 1924.55 Bannister & Schell was responsible for a number of tenement, church, stable, and store-and-loft buildings in Manhattan between 1903 and 1911. Bannister served as the Secretary of the New York State Board of Examiners, and on his own designed a number of churches, residences, and commercial buildings. The complex construction on the Morse Building, which included extensive foundation work, was performed between April 1901 and March 1902. The building’s owner, Charles Ward Hall (c. 1877-1936), a graduate of Cornell University (1895), was the engineer; his firm, Hall & Grant Construction Co., was general contractor. That firm, and Joseph W. Cody Contracting Co., of which Hall was president, had offices here. The Engineering Record described the architectural changes on the exterior in 1901 as follows: The architects decided to lighten the color and change the style. The lower stories have been modified by facing them with light-colored artificial stone, replacing the old portico by a new one of Indiana limestone and redesigning the main entrance. The new upper stories are faced with light-colored [cream] brick and have an enriched cornice separating the upper from the middle section. 56 Montgomery Schuyler, highly critical of the alterations, included the building in his “Architectural Aberrations” column in Architectural Record in 1902. He described the upper stories: For the former respectable top is substituted two stories of plain red brick piers with iron sashes, window frames, and a balcony projected upon huge corbels of sheet metal, and four additional stories are added above in white brick, with the same metal window framing, the whole concluded with a Grecian cresting, also in sheet metal. 57 The design of the upper stories is actually quite handsome. The new cornice that capped the 10th story (no longer extant), separating the form of the earlier building from the added four stories, featured a projecting balcony supported by enormous scroll brackets. The high terminating cornice is ornamented by stylized anthemia acroteria. Sarah B. Landau hypothesized that the shift in color for the addition and alteration of the Morse Building reflected the influence of the recently-built Broadway Chambers Building (1899-1900, Cass Gilbert), 277 Broadway, which epitomized the tripartite columnar base-shaft-capital form, but differentiated the sections by color and material.58 The name of the remodeled structure was changed to the Nassau-Beekman Building. A 1902 advertisement offered “Floors and offices at moderate rents, suitable for lawyers and parties connected with the paper trade.”59 Later History 60 Charles Ward Hall lost the Nassau-Beekman Building to foreclosure by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. in 1918. (Hall became a pioneer in the design of flying boats and airplanes as early as 1916, was president of the Aluminum Aircraft Corp. of Bristol, Pa, and died in 1936 while flying an aluminum experimental plane). In 1919, the building was transferred to the Second United Cities Realty Corp., one of the four real estate entities within United Cities Realty Corps. (established c. 1905), under the control of William E. Harmon & Co. (later Harmon National Real Estate Corp.), that operated also in Chicago; Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Duluth, Minn.; and Joplin, Mo. The name of the structure was changed again, to the United Cities Realty Building, with the offices of that firm and the Harmon company located here. In 1942, the property reverted to the Metropolitan Life Insurance Co. It was acquired in 1945 by Nassau Offices, Inc.; transferred to a group of investors in 1951, who conveyed it in 1952 to Clarendon Building, Inc. (later 140 Nassau Street Corp.); and was acquired by Chatham Associates, Inc., 8 in 1968. The base was altered again c. 1965, and the balcony/cornice (1901-02) above the 10th story was removed.61 The Morse (later Nassau-Beekman) Building was originally constructed on Manhattan Tax Map Block 101, Lot 26; in 1967, the portion of Tax Map Block 101 on which the building stands was merged with the block to the east, so that it is now part of Tax Map Block 100. The building was purchased in 1972 by Pace College, which was acquiring a number of historic properties in the vicinity. After a proposal to demolish them for a large office tower fell through, Pace sold this property in 1979 to 140 Nassau Street Associates, an entity of MJR Development Corp., controlled by Martin Raynes (who also purchased the Potter Building across the street). After conversion to cooperative loft apartments, part of a trend in changing downtown buildings from office to residential use, title passed in 1980 to 140 Nassau Residence Corp. Description The 14-story Morse Building is located at the northeast corner of Beekman and Nassau Streets. The current form of the building is the result of three periods of construction. The building is arranged horizontally into three sections: a two-story base (c. 1965); a 6-story original (1878-80) midsection consisting of two similar superimposed subsections; and a 6-story upper section consisting of two remodeled stories and four stories added in 1901-02 (a balcony/cornice added above the 10th story in 1901-02 was removed c. 1965). Each major facade is articulated vertically by monumental pilasters, with three sections on Nassau Street and two sections on Beekman Street. One-over-one double-hung wood-framed windows (with transoms in the round arches) have been replaced c. 1986 by anodized aluminum windows (except for the 8th story, which are mostly wood). Base The two lower stories were remodeled in a simplified neo-Classical style c. 1965 with a facing of concrete (now painted). The deeply inset main entrance on Nassau Street, with polished black granite reveals and multipane glass and metal doors and windows, has a 2-story molded surround and is flanked by 2-story pilasters. There are also 2-story pilasters at the north end of the building on Nassau Street, and at the center and the eastern end of the Beekman Street facade. The ground story has four storefront bays on each facade, with the corner having a storefront entrance that interrupts the corner pier. Ground-story alterations include rolldown gates, storefronts on Nassau Street, metal panels on Beekman Street, awnings, and signage. The second story of each facade has five rectangular windows flanked by pilasters, above molded spandrel panels; the second story is capped by a molded cornice. Midsection The intact 6-story, 1878-80 midsection, clad in polychrome (deep red and black) brick and terra cotta, is articulated as two sub-sections, each having one story of round-arched fenestration surmounted by two stories with paired segmental-arched fenestration set within segmental arches. Each major facade is articulated vertically by monumental pilasters, with three sections on Nassau Street and two sections on Beekman Street. The facades are further elaborated by brick patterning, corbelling, and moldings, and terra-cotta sills, sillcourses and foliate rondels. The 8th-story pressed metal cornice (1901-02) was replaced by one in fiberglass c. 2004. Some red bricks were replaced at that time. All of the original terra-cotta sillcourses along the Beekman Street facade and many of the sillcourses on the Nassau Street facade, and some units of the terra-cotta sills, were replaced by cast stone c. 2004. Upper Section The 6-story upper section (1901-02) consists of: two existing stories that were reconstructed and the pilasters re-faced with the original red brick, then terminated by a projecting balcony/cornice supported by enormous scroll brackets (this was removed c. 1965, and the area parged); a 3-story section having monumental cream-colored brick pilasters (the major ones having panels), capped by a molded pressed metal cornice supported by corbels (replicated in fiberglass c. 1995); and an attic story, terminated by a molded metal cornice ornamented by stylized anthemia acroteria (replicated in fiberglass c. 1995). Each story has tripartite window groups with metal framing and paneled metal spandrels. The cream brick was painted a reddish color at some point, but that paint is currently wearing away. There is a tall concrete elevator enclosure (c. 1901-02) on the roof. Eastern Facade Articulation of the Beekman Street facade continues by a corner return on the upper stories. This facade, pierced by fenestration, has been parged and painted. 9 1. New York County, Office of the Register, Liber Deeds and Conveyances; New York City Directories (1878-91); “Morse Family Tree,” www.morsehistoricsite.com website; “Samuel Finley Breese Morse” and “Sidney Edwards Morse,” Dictionary of American Biography [DAB] 7 (N.Y.: Chas. Scribner’s Sons, 1934), 247-252; “Sidney Edwards Morse” and “Richard Cary Morse,” Appleton’s Cyclopaedia of American Biography (N.Y.: D. Appleton & Co., 1889), 428; “The New-York Observer,” Moses King, King’s Handbook of New York (N.Y.: M. King, 1892), 584-585; Sidney E. Morse obit., New York Times [NYT], Dec. 24, 1871, 3; Sidney E. Morse & Co., advertisement, NYT, Mar. 22, 1879, 8; G. L. Morse obit., NYT, Jan. 13, 1891, 2; “G. Livingston Morse’s Will,” NYT, Jan. 18, 1891, 10; Sidney E. Morse obit. notice, NYT, Nov. 14, 1908, 9; NYC, Dept. of Buildings, Manhattan, Plans, Permits and Dockets (NB 409-1878); “An Old Landmark Doomed,” NYT, Apr. 21, 1878, 5; “The Morse Building, New York,” Real Estate Record & Builders’ Guide [RERBG], Jan. 18, 1879, 44-45; “Artistic Brickwork -- the Morse Building,” Carpentry & Building, June 1879, 101-103, and July 1879, 121-123; “Morse Building,” The Manufacturer & Builder, May 1881, 104B; Record and Guide, A History of Real Estate, Building and Architecture in New York City (N.Y.: Arno Press, 1967), reprint of 1898 edition, 515, 560; Sarah B. Landau and Carl Condit, Rise of the New York Skyscraper, 1865-1913 (New Haven: Yale Univ. Pr., 1996), 102-107; Susan Tunick, Terra-Cotta Skyline (Princeton: Princeton Archl. Pr., 1997); Robert A.M. Stern, Thomas Mellins, and David Fishman, New York 1880 (N.Y.: Monacelli Pr., 1999), 410-412, 1069. 2. King, 584. 3. “Work Among the Builders: Downtown Improvements,” NYT, June 2, 1878, 5. 4. “Index of Current Work,” American Architect & Building News [AABN], June 1, 1878, VIII, and Mar. 8, 1879, VIII. 5. “The Morse Building, New York,” RERBG, 44. 6. King, 782. 7. Landau and Condit, 105. 8. “Sky Building in New York,” The Building News, Sept. 7, 1883, 364. 9. “Stores, &c, to Let,” NYT, Mar. 21, 1880, 11. 10. “The Hardware Centre,” RERBG, Dec. 31, 1881, 1208. 11. “All About Rents,” RERBG, Feb. 11, 1882, 120. 12. “Real Estate,” RERBG, May 20, 1882, 501. 13. “Sky Building...”. 14. While a common method of fireproofing metal joists and beams had been the use of brick arches below and poured concrete above, in the 1870s numerous patent systems for fireproofing were introduced, including that of firebrickmaker Balthasar Kreischer, who patented a system of flat-arch hollow tiles in 1871 (this system was first employed in New York in the U.S. Post Office in 1872-73). 15. Gerard Wolfe, New York: A Guide to the Metropolis (N.Y.: McGraw-Hill, 1994), 74-77; Federal Writers’ Project, New York City Guide (N.Y.: Octagon Bks., 1970), reprint of 1939 edition, 99-100; Edwin Friendly, “Newspapers of Park Row,” Broadway, the Grand Canyon of American Business (N.Y.: Broadway Assn., 1926), 129-134; Record and Guide, 50-52; Andrew S. Dolkart, Lower Manhattan Architectural Survey Report (N.Y.: Lower Manhattan Report prepared by JAY SHOCKLEY Research Department NOTES 10 Cultural Council, 1988). 16. Printing House Square is at the northern end of Nassau Street at Park Row and Spruce Street. Among the more significant structures of the mid-nineteenth century located in the vicinity were the New York Times Building (1857-58, Thomas R. Jackson; demolished), 40 Park Row, and New York Herald Building (1865-67, Kellum & Son; demolished), Broadway and Ann Street. 17. All of the extant buildings are designated New York City Landmarks. The shift of newspapers away from downtown began after the New York Herald moved to Herald Square in 1894 and the New York Times moved to Longacre Square in 1904, though the New York Evening Post constructed a new building in 1906-07 (Robert D. Kohn) at 20 Vesey Street (a designated New York City Landmark), and the majority of newspapers remained downtown through the 1920s. 18. LPC, Bennett Building Designation Report (LP-1937)(N.Y.: City of New York, 1995), prepared by Gale Harris, and Ladies’ Mile Historic District Designation Report (LP-1609)(N.Y.: City of New York, 1989), vol. 2, 1014; Dennis S. Francis, Architects in Practice, New York City 1840-1900 (N. Y.: Comm. for the Pres. of Archl. Recs., 1979); James Ward, Architects in Practice, New York City 1900-1940 (N.Y.: Comm. for the Pres. of Archl. Recs., 1989); Trow’s N.Y.C. Directory (1876-1884); “Benjamin Silliman” [father and grandfather], DAB 9, 160-164; Elizabeth Daniels, Main to Mudd: An Informal History of Vassar College Buildings (Poughkeepsie: Vassar Coll., 1987), 24-25; “Vassar Brothers Laboratory...,” AABN, May, 29, 1880, 237; “Orange Music Hall...,” AABN, Aug. 28, 1880, 102; “Private Hospital...,” AABN, Sept. 4, 1880, 114; “The Singer Building...,” Building, Jan. 2, 1886, 6; Silliman obit., NYT, Feb. 6, 1901, 9, and AABN, Feb. 16, 1901, 49; George Martin Huss, “Benjamin Silliman: A Correction,” AABN, Feb. 23, 1901, 63; “James Mace Farnsworth,” www.familysearch.com website; Landau and Condit. 19. “Benjamin Silliman,” DAB, 160. 20. “The Morse Building...,” RERBG, 45. 21. These buildings are located in the Ladies’ Mile Historic District. 22. The Bennett Building, 139 Fulton Street, originally built in 1872-73 to the design of Arthur D. Gilman, is a designated New York City Landmark. 23. Huss. 24. Landau and Condit; Record and Guide, 515, 560; “Artistic Brickwork -- the Morse Building,” Carpentry & Building, June 1879, 101-103, and July 1879, 121-123; “Morse Building,” The Manufacturer & Builder; Tunick. 25. “The Morse Building...,” RERBG, 45. 26. Landau and Condit, 104-105. 27. “Correspondence,” AABN, Jan. 11, 1879, 12. 28. “Correspondence. Iron Fronts – New Office Buildings,” AABN, July 5, 1879, 6. 29. “The Latest Additions to New York Architecture,” The Manufacturer & Builder, June 1879, 140. 30. Montgomery Schuyler, “Recent Building in New York -- II. Commercial Buildings,” AABN, Apr. 16, 1881, 183. 31. “Artistic Brickwork...”; “The Morse Building, New York,” AABN, Oct. 9, 1880, pl. 250. 32. “Sky Building...”. 33. Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer, “Recent Architecture in America,” The Century, Aug. 1884, 517. 34. King, 782. 35. AABN, Feb. 16, 1901. 36. Schuyler, “Architectural Aberrations -- No. 18. The Nassau-Beekman,” Architectural Record, May 1902, 96. 11 37. The Bennett Building (1872-73) is essentially of the earlier generation of office buildings and something of an anomaly, clad entirely in cast iron. Among contemporary, though later, buildings there are only the Temple Court Building (1881-83), the Potter Building (1883-86), and the rear facade of the Standard Oil Building (1884-85). 38. This section was adapted from: LPC, Potter Building Designation Report (LP-1948) (N.Y: City of New York, 1996), prepared by Jay Shockley. 39. Schuyler, “Recent Building...”. 40. “The Morse Building...,” RERBG, 45. 41. Peerless Brick Co., advertisement, AABN, Jan. 3, 1880, XI. 42. “Building Specialties, Etc. Novelty in Bricks. – The Peerless Company, of Philadelphia.,” AABN, May 17, 1879, VIII. 43. Examples of this period include the Trinity Building (1851-53, Richard Upjohn; demolished), 111 Broadway, St. Denis Hotel (1853, James Renwick; altered), 797 Broadway, and Cooper Union Building (1853-58, Frederick A. Petersen), a designated New York City Landmark. See: Jay Shockley and Susan Tunick, “The Cooper Union Building and Architectural Terra Cotta,” Winterthur Portfolio (Winter 2004), 207-227. 44. Walter Geer, Terra-Cotta in Architecture (N.Y.: Gazlay Bros., 1891), 20. Advantages seen in terra cotta for both exterior architectural ornament and interior fireproofing included its fireproof properties, strength, durability, lower cost and weight in shipping and handling, the relative ease with which elaborate decoration could be molded, and the retention over time of crisp ornamental profiles compared to stone. 45. “The Use of Terra Cotta in Building,” RERBG, Mar. 3, 1883, 85. 46. The Long Island Historical Society (now Brooklyn Historical Society), 128 Pierrepont Street, Brooklyn, is located in the Brooklyn Heights Historic District and is a designated New York City Interior Landmark. 47. Boston Terra Cotta Co., Catalogue (Boston: P.H. Foster & Co., 1885), 2. 48. “Correspondence. Iron Fronts...”. 49. James Taylor, “The History of Terra Cotta in New York City,” Architectural Record, Oct.-Dec., 1892, 144. 50. NYC Directories (1891-1910); NY County; NYC, Dept. of Buildings (Alt. 2617-1900); LPC, Architects files; Francis, 13, 67; Ward, 5; “In Mr. Niles’s Place,” NYT, Nov. 10, 1889, 11; “City and Suburban News,” NYT, Sept. 27, 1891, 3; “All Gazed at the Long Crack,” NYT, Oct. 16, 1894, 9; “The Morse Building Mortgaged,” and “Recorded Real Estate Transfers,” NYT, Feb. 8, 1895, 8, 12; “To Foreclose on the Morse Building,” NYT, Aug. 20, 1898, 10; “Referees’ Notices,” NYT, Mar. 21, 1899, 13, and Apr. 18, 1899, 15; “The Auction Room,” NYT, Apr. 6, 1899, 12, and Apr. 27, 1899, 12; “Reported Deal for the Morse Building,” NYT, Nov. 13, 1900, 12; “The Morse Building Sale,” NYT, Nov. 14, 1900, 14; “In the Real Estate Field,” NYT, Nov. 18, 1900, 11, and Dec. 1, 1900, 11; “Alterations. Borough of Manhattan,” RERBG, Dec. 22, 1900, 887; “The Building Department,” NYT, Dec. 23, 1900, 10; “The Rights of Builders,” NYT, June 5, 1901, 6, and Oct. 19, 1901, 16; “The Nassau-Beekman Building Lien,” NYT, Mar. 29, 1902, 14; “Legal Notes,” NYT, May 3, 1902, 16; “Joseph W. Cody Contracting Co.,” NYT, July 17, 1903, 12; R.M. Schell obit., NYT, July 29, 1924, 15; W.P. Bannister obit., NYT, Jan. 10, 1939, 25; Charles W. Hall obit., NYT, Aug. 22, 1936, 15. 51. “The Ruins,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Feb. 1, 1882, 4. 52. King, 782. 53. Albert E. Smith, with Phil A. Koury, Two Reels and a Crank (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1952), 42-44. 54. NYT, Nov. 14, 1900. 55. Schell was actively involved as a trustee and donor, and in the fresh air work, of the George Junior Republic, a charitable institution established in 1895 for troubled adolescents, in Freeville, N.Y. 56. “Reconstructing the Morse Building, New York,” The Engineering Record, Nov. 2, 1901, 422-424. 12 57. Schuyler, “Architectural Aberrations .” 58. The building is a designated New York City Landmark. 59. “Nassau-Beekman Building” advertisement, NYT, Feb. 20, 1902, 14. 60. NY County; “Ten in Elevator Fall Thirty Feet,” NYT, Mar. 4, 1910, 11; “Nassau St. Towers Swept by Flames,” NYT, Apr. 4, 1916, 24; “Real Estate Field: Title Passes to Nassau Street Building,” NYT, Nov. 5, 1918, 20; “Recorded Leases,” NYT, Aug. 23, 1919, 15; United Cities Realty Corps., advertisement, NYT, Apr. 30, 1920, 23; NYC Directory (1933-34); “Building on 57th Street Leased...,” NYT, Sept. 24, 1926, 39; “Manhattan Transfers,” NYT, Oct. 27, 1945, 30, and Dec. 27, 1951, 42; “Alterations -- Manhattan,” RERBG, Mar. 27, 1965, 18; “Wall St. Image Facing Change as Apartments Replace Offices,” NYT, July 29, 1979, R1-2; “2 Downtown Office Buildings to be Converted to Co-ops,” NYT, Apr. 4, 1980, 16. 61. According to RERBG, Mar. 27, 1965, 18: [John J.] Tudda & [Richard R.] Scherer, architects, performed a $30,000 alteration. 13 FINDINGS AND DESIGNATION On the basis of a careful consideration of the history, the architecture, and other features of this building, the Landmarks Preservation Commission finds that the Morse Building has a special character and a special historical and aesthetic interest and value as part of the development, heritage, and cultural characteristics of New York City. The Commission further finds that, among its important qualities, the current form of the Morse Building results from three periods of construction, the original (1878-80), as well as alterations in 1901-02 and c. 1965, and that today, the structure’s 6-story midsection, with two articulated facades featuring round- and segmental-arched fenestration, is, in part, the earliest surviving (as well as one of the very few surviving) tall “fireproof” New York office building of the period prior to the full development of the skyscraper; that the original 8-story (plus raised basement and attic) Morse Building was a speculative commission by Sidney E. Morse and G. Livingston Morse, cousins who were sons of the founders of the religious newspaper The New-York Observer, and nephews of Samuel F.B. Morse, the artist and inventor of the electric telegraph; that, the first major New York design of architects [Benjamin, Jr.] Silliman & [James M.] Farnsworth, employing a generally-praised stylistic combination of Victorian Gothic, neo-Grec, and Rundbogenstil, the building was located in the center of the city’s newspaper publishing and printing industries, as Park Row and Nassau Street were redeveloped with significant tall office buildings; that it is an early example of the use of brick and terra cotta for the exterior cladding of office buildings in that period, with intricate polychrome brickwork, supplied by the Peerless Brick Co. of Philadelphia and among the finest of its time surviving in New York City, featuring hues of deep red contrasted with glazed black, the latter employed ornamentally, largely to emphasize the outlines of the fenestration, and with terra cotta manufactured by the Boston Terra Cotta Co., one of the first East Coast firms, used for details such as sillcourses and rondels; that just 20 years after its completion, the Morse Building was considered small and old-fashioned compared to very tall 1890s steel-framed skyscrapers, and that the Nassau-Beekman Building, as it was re-named, was altered in 1901-02 to the “Edwardian” neo-Classical style design of architects [William P.] Bannister & [Richard M.] Schell, with a remodeled base, reconstructed upper two stories, capped by a projecting balcony/cornice supported by enormous scroll brackets, and four additional steel-framed stories clad in cream-colored brick, bringing it to 14 stories, and that the shift in color and style of this alteration apparently reflected the influence of the recently-built Broadway Chambers Building (1899-1900, Cass Gilbert); and that, in its later history, the former Morse Building was headquarters of the United Cities Realty Corp. (1919-42), the base of the structure was altered again c. 1965 and the 10th-story balcony/cornice was removed, and the building was converted from office to residential use in 1980. Accordingly, pursuant to the provisions of Chapter 74, Section 3020 of the Charter of the City of New York and Chapter 3 of Title 25 of the Administrative Code of the City of New York, the Landmarks Preservation Commission designates as a Landmark the Morse Building, 138-142 Nassau Street (aka 10-14 Beekman Street), Borough of Manhattan, and designates Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 100, Lot 26, as its Landmark Site. Robert B. Tierney, Chair; Pablo Vengoechea, Vice-Chair Joan Gerner, Roberta Brandes Gratz, Christopher Moore, Richard Olcott, Thomas Pike, Elizabeth Ryan, Commissioners Morse Building, rendering, Silliman & Farnsworth Source: Record & Guide, A History of Real Estate, Building and Architecture in New York City (1898) Morse Building, rendering Source: The Manufacturer & Builder (May 1881) Morse Building Source: Moses King, King’s Handbook of New York (1892) Morse Building, next to the American Tract Society Building (left) Source: Remington Standard Typewriter Co., A Few Office Buildings in New York (1895) Nassau-Beekman Building Source: “Architectural Aberrations,” Architectural Record (May 1902) Morse Building (later Nassau-Beekman Building), 138-142 Nassau Street (aka 10-14 Beekman Street) Photo: Carl Forster (1999) Morse Building (later Nassau-Beekman Building) Photo: Carl Forster Morse Building (later Nassau-Beekman Building), midsection Photo: Carl Forster Morse Building (later Nassau-Beekman Building), midsection detail Photo: Carl Forster Morse Building (later Nassau-Beekman Building), midsection detail Photo: Carl Forster Morse Building (later Nassau-Beekman Building), upper section Photo: Carl Forster A |

|

|

links |

|