|

New York Architecture Images-Seaport and Civic Center Temple Court Landmark 5 Beekman Street |

|

architect |

Silliman & Farnsworth. |

|

location |

5 Beekman Street (or 119-133 Nassau Street), Lower Manhattan. |

|

date |

1881-83 |

|

style |

Queen Anne, neo-Grec, and Renaissance Revival motifs |

|

construction |

red Philadelphia brick, tan Dorchester stone, and terra cotta above a two-story granite base. 9 stories in main structure (10 in towers and annex) |

|

type |

Office Building |

|

|

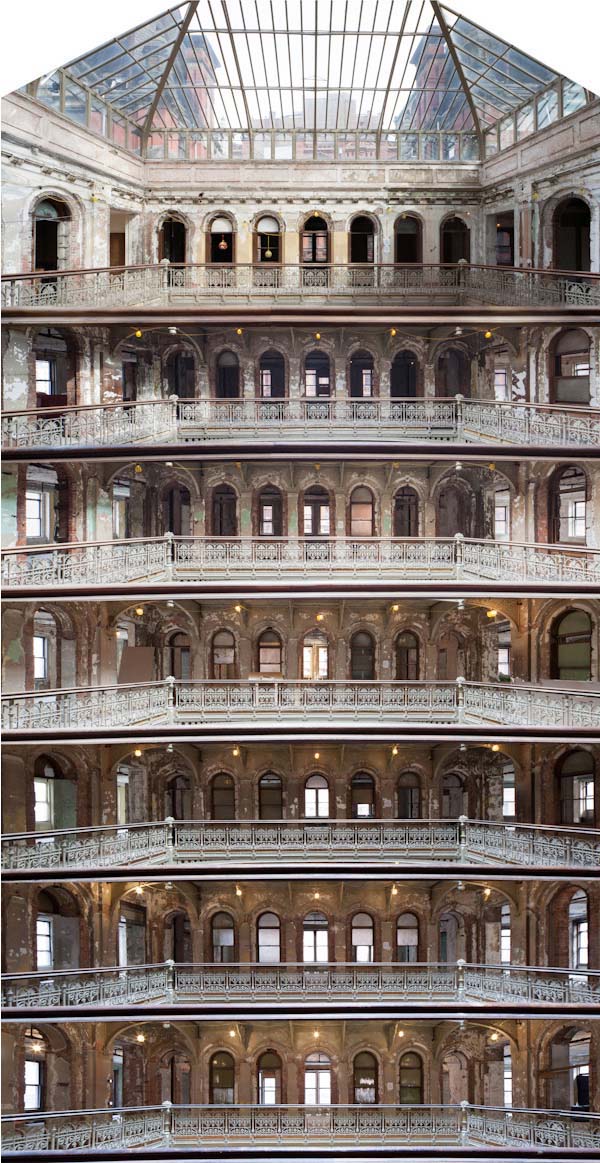

Originally built in 1881-1883, 5 Beekman was the first high-rise building in New York. GB Lodging and its affiliate GFI Development Company are converting this unique, historic structure, together with an adjacent site on Nassau Street, into a luxury hotel consisting of 285 guestrooms and 68 residences. The project will total approximately 340,000 square feet, include a 40+ story tower and intends to be a catalyst in the transformation of the Fulton Nassau Historic District. The hotel is scheduled to open late 2015. |

|

images |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Images- special thanks to- http://www.scoutingny.com/the-abandoned-palace-on-beekman-street/ | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Above: Based on- Royal Courts of Justice (near Temple tube station) Built: 1866- 1882 Architectural style: Gothic Revival architecture Architect: George Edmund Street http://www.london-architecture.info/LO-058.htm |

| TEMPLE COURT BUILDING AND ANNEX, 3-9 Beekman Street (a.k.a. 119-133 Nassau Street and 10 Theatre Alley), Manhattan. Built 1881-83, [Benjamin, Jr.] Silliman & [James M.] Farnsworth, architects; Annex built 1889-90, James M. Farnsworth, architect. Designated February 10, 1998; LP-1967. | |

|

Temple Court Building and Annex Summary The Temple Court Building and Annex consists of two connected structures on the designated Landmark Site. The nine-story (ten stories in certain portions) Temple Court Building was commissioned by Eugene Kelly, an Irish-American multi-millionaire-merchant-banker, and built in 1881-83 to the design of architects Silliman & Farnsworth. Executed in red Philadelphia brick, tan Dorchester stone, and terra cotta above a two-story granite base, the handsome vertically-expressed design employs Queen Anne, neo-Grec, and Renaissance Revival motifs. Today, Temple Court is the earliest surviving, essentially unaltered, tall "fireproof" New York office building of the period prior to the full development of the skyscraper. Furthermore, it is an early example of the use of brick and terra cotta for the exterior cladding of tall office buildings in the 1870s and 80s, as well as a rare surviving office building of its era constructed around a full-height interior skylighted atrium. Its two towers foreshadow the pyramidal form that later became popular for skyscrapers. The Annex to the building, clad in Irish limestone on its principal, Nassau Street facade, was constructed for Kelly in 1889-90 to the design of James Farnsworth, in an arcaded Romanesque Revival style that complements the original building. Temple Court's significance is enhanced by its visibility as it rises above the low buildings of Park Row facing City Hall Park, its prominent towers, and its articulated facades on three sides. Eugene Kelly The Temple Court Building was commissioned by Eugene Kelly in 1881. Born in Ireland and apprenticed to a draper, Kelly (1808-1894) immigrated to New York City around 1835 to work as a clerk for Donnelly & Co., one of New York's foremost dry goods importers. With the Donnelly s' assistance, he established a successful drygoods business on his own in Maysville, Ky., and later opened a branch of the Donnelly firm in St. Louis, Mo. Kelly had married Sarah Donnelly, sister of his former employer. After her death, he retired a wealthy man but, swept up in the "gold fever" of 1849, moved to San Francisco in 1850 and helped to found Donohoe, Murphy, Grant & Co., another drygoods firm. In 1857 he married Margaret Hughes, niece of New York's first archbishop, John J. Hughes. By 1861 Kelly had also helped found two banking houses, Donohoe, Ralston & Co. (known as Donohoe, Kelly & Co. after 1864)4 in San Francisco, and Eugene Kelly & Co. in New York City, the latter the main focus of Kelly's professional attention upon his return to New York. After the Civil War, Kelly invested in the reconstruction of Southern railroads and was a founder of the Southern Bank of Georgia, in Savannah. His various financial endeavors made him a multimillionaire, and Kelly served as a director of the Bank of New York, Emigrant Savings Bank, National Park Bank, Lloyd's, and Equitable Life Assurance Society. Active in Democratic and Irish-American politics, as well as numerous civic causes, he was chairman of the state's Electoral Committee (1884); member of the Board of Education for thirteen years; member of the Washington Arch and Statue of Liberty committees; trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; president of the National Federation of America; and treasurer of the Irish Parliamentary Fund. He was also a major philanthropist of Catholic institutions, serving on the committee for the building of St. Patrick's Cathedral5 (begun by archbishop Hughes), and as a trustee of Seton Hall College, and a founder and trustee of Catholic University in Washington, D.C. After separating from his San Francisco firm in 1890, Kelly retired with an estate estimated at between ten and fifteen million dollars in 1892. Eugene Kelly & Co. was dissolved in 1894, several months prior to his death. The Lady Chapel of St. Patrick's Cathedral (1901-06, Charles T. Matthews), constructed through a memorial donation of his wife and sons, contains the burial vault of Eugene Kelly and other members of the Kelly family. The Tall Office Building in New York City in the Early 1880s During the nineteenth century, commercial buildings in New York City developed from four-story structures modeled on Italian Renaissance palazzi to much taller skyscrapers. Made possible by technological advances, tall buildings challenged designers to fashion an appropriate architectural expression. Between 1870 and 1890, nine- and ten-story buildings transformed the streetscapes of lower Manhattan between Bowling Green and City Hall. During the building boom following the Civil War, building envelopes continued to be articulated largely according to traditional palazzo compositions, with mansarded and towered roof profiles. The period of the late 1870s and 1880s was one of stylistic experimentation in which commercial and office buildings in New York incorporated diverse influences, such as the Queen Anne, Victorian Gothic, Romanesque, and neo-Grec styles, French rationalism, and the German Rundbogenstil under the leadership of such architects as Richard M. Hunt and George B. Post. New York's tallest buildings — including the seven-and-one-half-story Equitable Life Assurance Co. Building (1868-70, Gilman & Kendall and George B. Post) at Broadway and Cedar Street, the ten-story Western Union Building (1872-75, George B. Post) at Broadway and Liberty Street, and the ten-story Tribune Building (1873-75, Richard M. Hunt), at 154 Nassau Street, all now demolished — incorporated passenger elevators, iron floor beams, and fireproof building materials. Fireproofing was of paramount concern as office buildings grew taller, and by 1881-82 systems had been devised to "completely fireproof" them. An additional consideration in office building design was to provide maximum light and ventilation, for which contemporary architects devised several solutions. While some tall buildings in New York had open interior light wells or courts, George B. Post is credited as one of the first architects to introduce and popularize major light courts that faced the street. Another variant was the interior court or atrium covered by a skylight. The Temple Court Building utilized the successful design, construction, fireproofing, and planning techniques of these earlier buildings. "Newspaper Row": Park Row and Nassau Street The vicinity of Park Row, Nassau Street, and Printing House Square, roughly from the Brooklyn Bridge to Ann Street, was the center of newspaper publishing in New York City from the 1840s through the 1920s, while Beekman Street became the center of the downtown printing industry. Beginning in the 1870s, this area was redeveloped with tall office buildings, most associated with the newspapers, and Park Row (with its advantageous frontage across from City Hall Park and the U.S. Post Office) and adjacent Nassau Street acquired a group of important late-nineteenth-cenrury structures: Tribune Building (1873-75, demoUshed); Morse Building (1878-80; 1900-02); Temple Court Building and Annex (1881-83; 1889-90); Potter Building (1883-86, N.G. Starkweather), 35-38 Park Row;15 New York Times Building (1888-89, George B. Post; 1904-05, Robert Maynicke), 40 Park Row; World (Pulitzer) Building (1889-90, George B. Post, demolished), 53-63 Park Row: American Tract Society Building (1894-95, R.H. Robertson), 150 Nassau Street; and Park Row Building (1896-99, R.H. Robertson), 15 Park Row. Construction and Design of the Temple Court In April 1881, Silliman & Farnsworth filed for the construction of a nine-story (ten stories in certain portions) office building for Eugene Kelly, to be located at the southwest corner of Beekman and Nassau Streets on the lot that Kelly had acquired in 1868 from the National Park Bank, of which he was a director.18 Both the New York Times and the Real Estate Record & Guide carried lengthy and detailed descriptions of the proposed $400,000 structure, to be known as the Kelly Building. According to the Times, "it will be one of the finest in the lower part of the City" and was to be "constructed of granite to the third story, above which it will be Philadelphia brick, lad in red mortar, with Dorchester stone trimmings, and terra cotta panels between the windows." Construction began in May under builder Richard Deeves; completion was originally anticipated on May 1, 1882, although a bricklayers strike in 1881 was undoubtedly one factor that contributed to a different outcome. The Kelly Building was among the first of the major downtown office buildings to be erected after 1879, when recovery began from the financial Panic of 1873. Several notices in the Record & Guide during construction of the building indicated the shrewdness of Kelly's investment, as the nature of office buildings and the demand for space downtown changed. In December 1881 the weekly commented that the demand for offices is no longer confined to the neighborhood of the Stock, Mining, Cotton and Produce Exchanges. All the great industries which are represented in New York are using offices instead of stores, and these last are very profitable. Eugene Kelly paid $230,000for the lots on the corner of Nassau and Beekman streets. The building he erected is a very costly one, yet it is said it will net him a profit of 20 per cent, per annum. This was followed in February 1882 by the statement that in no part of the city has there been so great an increase in rents as in the great business centres, especially in the lower part of the island. . . The demand for well-located offices in Broad, Pine, Cedar, Wall and New streets, Exchange place and Broadway below Fulton street, is not only keeping pace, but fast outrunning the accommodations which have been provided, or which are nearing completion. Already many of the offices in the Marquand, Kelly, Mills, and Tribune structures are engaged, and at very fair figures. An item in March 1882 indicated that a new name for the Kelly Building had been chosen: "Temple Court is the name of the splendid building just erected. . . by Mr. Eugene Kelly. Persons who wish offices in this splendid building should see Messrs. Ruland & Whiting. . . without delay, as the offices are being rented rapidly. The building is fire-proof, and has all the modern office improvements.1,24 And in May 1882 was the further comment that "the Tribune, Times, Morse buildings and Temple Court are nearer the law courts, and better for lawyers and public offices." The Temple Court Building was completed in May 1883. Its design reflects the shift from the palazzo model for office buildings begun in the 1870s by Richard M. Hunt with the Tribune Building, among others. Temple Court was also one of the early tall office buildings that employed brick and terra-cotta cladding. The location on Beekman and Nassau Streets and Theatre Alley allows for three facades, each of which has a tripartite arrangement with end pavilions. The vertically-expressed design is organized by continuous piers, and the building is arranged horizontally into a base, midsection, and upper section. Articulation of the facades on Beekman and Nassau Streets (and the corner return on Theatre Alley), employing Queen Anne, neo-Grec, and Renaissance Revival motifs, is similar, the walls elaborated by ornamental stone capitals, cornices, bandcourses, corbelling, arches, and terra-cotta panels. (The remainder of the Theatre Alley facade below the roof is more simply articulated.) The building is capped by a two-story slate mansard roof with dormers and has two prominent corner towers with octagonal pinnacled roofs, intended "to obtain a striking and satisfactory effect making the building appear less high than it really is." The towers foreshadow the pyramidal form that later came to dominate skyscrapers. Temple Court provides an interesting contrast with the slightly earlier Morse Building, by the same architects, and the slightly later Potter Building, all three executed in red brick and terra cotta, at the same intersection of streets. As built, the interior of Temple Court featured an impressive polychrome atrium entered through the main entrance and adjoining entrance hall on Beekman Street; an open ironwork staircase surrounds the central of three elevators on the south side. More than two hundred feet square, rising nine stories, and covered by a large pyramidal skylight, the atrium has galleries supported by elaborate ornamental iron brackets and lined with iron railings surrounding it on each floor. Gallery floors are laid in encaustic tiles and gallery ceilings are formed by unusual ornamental cast-iron plates. The building's 212 offices were arranged so that they opened onto both the atrium and the exterior. An exterior light well to the south of the staircase provided further light to the interior. Construction of the building was considered "solidly fireproof," with iron floor beams, and exterior brick walls that varied in thickness from 52 inches in the foundations to 32 inches in the upper walls. As with most prominent tall buildings of the late nineteenth century in New York, contemporary comment on Temple Court was mixed. While Cornelius Mathews of The Manhattan. An Illustrated Literary Magazine, an early tenant, thought the building "stalwart and sumptuous," the British publication The Building News found "its architecture is nondescript, and it is surmounted by two towers, like donkey's ears, on its northern side, which give it a very unfortunate appearance." (Critic Montgomery Schuyler, however, had praised the design, prior to construction, for "that animation in the sky line.") King's Handbook in 1892 called it "one of the finest office-buildings in New York. . . an edifice that is creditable in architecture and pleasing in nomenclature. . . a modern building in every sense. . . the quaint towers of Temple Court, with their high pyramidal roofs, are unmistakable land-marks in the heart of New York, and point the way to the scenes of vast and momentous transactions in business and finance." New York 1895. Illustrated considered Temple Court "the pioneer among the great office buildings and the beginning of the revolution in these structures," and American Architect & Building News in 1901 called it "a popular and profitable structure. Today, the Temple Court Building is the earliest surviving (as well as one of the very few surviving), essentially unaltered, tall "fireproof New York office building of the mid-1870s to mid-1880s, the period prior to the full development of the skyscraper.35 Its significance is enhanced by the visibility of its location near City Hall Park, its prominent towers, and its three articulated facades. (For discussion of the Annex, see below.) Temple Court. Brick, and Architectural Terra Cotta in New York City The Temple Court Building is an early example of the use of brick and terra cotta for the exterior cladding of tall office buildings in the 1870s and 80s, a trend seen in such brick structures as the Boreel, Western Union, and Tribune Buildings/' As observed in 1881 by Montgomery Schuyler: the architects of the present generation found commercial New York an imitation of marble, either in cast-iron or in an actual veneer of white limestone. They are likely to leave it in brick. . . Whatever of interest has since been done in business buildings has been done in baked clay, more and more including the use of terra-cotta as well as of brick. The first of the noteworthy attempts to build in brick alone . . . was Messrs. Silliman and Farnsworth's Morse Building. . . While there had been several attempts in the 1850s to employ architectural ornament of terra cotta in New York, it was after the Chicago and Boston fires of 1871 and 1872 that terra cotta began to be used as a significant interior and exterior building material in the United States. Walter Geer noted that "by these fires it was conclusively demonstrated that fire-proof buildings could not be made of unprotected stone or iron, and that only brick and terra-cotta walls were practically fire-proof. This increased use of brick work, and of terra-cotta as a constructive and decorative material in connection with brick work, revived the demand for the manufacture of this material in or near New York."40 In the 1870s and early 1880s architectural terra cotta was often a color that matched stone (commonly brownstone, buff or red) that could be employed in pleasant juxtaposition with brick, or as a substitute for brownstone. The Record & Guide remarked that during this period "terra cotta is most generally used for the trimming and ornamentation of buildings, taking the form of panels, courses, friezes, small tiles, roofing tiles and paving blocks. " George B. Post was the leader in New York City in the use of exterior terra cotta, in his designs for the Braem House (1878-80), Long Island Historical Society (1878-81), New York Produce Exchange (1881-84), and Mills Building (1881-83). Among the other contemporary architects who employed terra cotta were Kimball & Wisedell, designers of the Casino Theater (1881-82), an early New York building having highly intricate, exotic terra-cotta ornament, and Silliman & Farnsworth. The Morse Building, with terra cotta by the Boston Terra Cotta Co., was then considered the first prominent New York office building to employ exterior terra cotta (though it was used sparingly for architectural details, in conjunction with molded red and black brick). Temple Court was an early and significant building to employ exterior architectural terra cotta, and is today a rare surviving example of a tall New York office building of its era employing exterior brick and terra cotta. The Skylighted_Atrium in Nineteenth-Century The nineteenth-century interior court or atrium covered by a skylight, a form that evolved in the United States for a variety of building types, allowed for both natural lighting and an enclosed, usually grand and highly decorative, volume of space. Carl Condit, in American Building Art: The Nineteenth Century, discussed the American use of the "skylighted interior court, or arcade," which he traced first to the three-story Arcade Building (1827-28, James C. Bucklin & Russell Warren), Providence, R.I. The concept was later "adapted to iron construction in New York in the 1850s in the five-story uptown A.T. Stewart Store (1859-62, John Kellum, demolished), Broadway and 10th Street. The skylighted atrium became a popular feature for arcades, hotels, libraries, exhibition halls, department stores, and office buildings, often in association with cast-iron framing and decoration. Two significant libraries that featured cast-iron galleries around skylighted courts were the four-story State Department Library (1871-75) in Alfred B. Mullett's State, War and Navy Building, Washington, and the seven-story Peabody Institute Library (1876-78, Edmund G. Lind), Baltimore. The Shillito Store (1878, James W. McLaughlin; altered and court filled in), Cincinnati, had a six-story interior court, while the Model Hall (c. 1878-80, Adolf Cluss & Paul Schulze) of the U.S. Patent Office Building, Washington, consisted of a long two-story skylighted gallery, and the Pension Building (1882-85, Montgomery C. Meigs), Washington, was constructed around a colossal three-and-one-half-stoiy court. In New York City, the New York Produce Exchange (1881-84, George B. Post, demolished), 2 Broadway, and the downtown A.T. Stewart Store (after its conversion to offices in 1883-84), among other buildings, had skylighted atriums that did not rise the full height of the structure (the courts were open above), a variant exemplified by the Rookery Building (1885-86, Burnham & Root), Chicago. Schuyler mentioned of the eight-story Boreel Building (1878-79, Stephen Decatur Hatch, demolished), 115 Broadway, its "interesting plan, which is a large glazed court upon which the inner offices open." The use of the full-height interior skylighted atrium culminated in the late nineteenth century in such prominent office and commercial buildings as the ten-story Society for Savings Building (1887-90, Burnham & Root; atrium filled in), Cleveland: the thirteen-story Chamber of Commerce Building (1888-89, Edward Baumann & Harris W. Huehl, demolished), Chicago; the twelve-story Guaranty Loan Building (1888-90, Edward T. Mix, demolished), Minneapolis; the five-story Cleveland Arcade (1888-90, John M. Eisenmann & George H. Smith), Cleveland; the nine-story Brown Palace Hotel (1889-92, Frank E. Edbrooke), Denver; the twenty-story Masonic Temple Building (1890-92, Burnham & Root, demolished), Chicago; the eight-story court of the U.S. Post Office (1892-99, Willoughby J. Edbrooke), Washington; and the five-story Bradbury Building (1893, George H. Wyman), Los Angeles. Temple Court is an early and rare surviving example of an office building of its era constructed around an interior skylighted atrium. Construction of the Temple Court Annex The success of the Temple Court Building led Eugene Kelly to plan an expansion. James Farnsworth filed in January 1889 for the construction of an Annex, on the adjacent lot to the south (at 119-121 Nassau Street) that Kelly had acquired in 1886. Expected to cost $150,000, the ten-story Annex was originally to be clad in granite, brick, and Dorchester stone, the materials of the original building. An amendment, however, was filed by Farnsworth on March 1, "substituting a new design for front, to be constructed of 'Irish limestone' as per new plans and elevations" and resulting in an estimated cost of about $200,000. In May, the Record & Guide clarified that "the front will be a limestone from Balinasloe, Ireland, and the design will have a tendency toward the Romanesque." Construction by September 1889 was "nearly up to the top floor" and was considered by the Record & Guide "a remarkable example of quick work." In February 1890, the Record & Guide noted that "the handsome addition to Temple Court. . . is now being rented in single rooms and suites for office purposes.. . The building is certainly one of the best of the down-town structures." Labor issues, threatening to delay completion, were satisfactorily resolved in the spring of 1890; after a strike was called on the Temple Court Annex due to the contractor's use of non-union masonry workers, Kelly strongly urged the contractor to come to terms with the union, and the building was completed by the target date of May 1. King's Handbook in 1892 thought that the front (Nassau Street) Annex facade "presents an attractive and imposing appearance." Running through the block from Nassau Street to Theatre Alley, the Temple Court Annex was framed with iron. The original Buildings Department application indicated that the front and rear walls were to be "carried on girders and columns." Plans were amended to include some plate girders, as well as the notation that "all iron construction will be fireproofed with terra cotta blocks, to make same entirely fireproof. The Annex suffered a fire, of unknown origin, in April 1893 that destroyed offices on the top four floors. This fire was of great interest to those in construction, due to the fact that it was "the most serious fire which has ever occurred, so far as we recall, in a thoroughly fireproof office building," according to Engineering News, and that "there have been so few practical tests of the modern system of fireproof construction that there is much doubt and dispute as to the actual behavior of fireproofing materials when placed in actual use and subjected to the ordeal of a conflagration. " The fire was also covered in a front-page article in the New York Times The structure of the Annex and most of the fireproofing remained intact; furthermore, the original building was not damaged. Later History Throughout its history, Temple Court has housed a wide variety of office and commercial tenants. Among the original tenants were Ruland & Whiting, real estate agents (established in 1867), the Nassau Bank, and The Manhattan. An Illustrated Literary Magazine. Other tenants have included lawyers, accountants, publishers, press agents, insurance and advertising agents, architects, business representatives, detectives, unions, organizations, and employment agencies. The trustees of Eugene Kelly's estate in 1907 transferred the Temple Court Building and Annex (located on separate lots until 1961-62) to the Temple Court Co. (Thomas Hughes Kelly, president). Thomas H. Kelly (1865-1933), son of the original owner, was trained as a lawyer but concentrated on the management of the various properties he had inherited, as well as on official corporate and institutional duties. He was considered "one of the most important lay dignitaries of the Catholic Church in the United States," according to the New York Times, serving as Papal Chamberlain for thirty years. Emigrant Industrial Savings Bank, which held the mortgage, took over the properties in 1942. Conveyed in 1945 to the Wakefield Realty Corp., they were acquired by the Region Holding Corp. (Rubin Shulsky, president) in 1946. The properties were transferred in 1953 to the Larsan Holding Corp./Satmar Realty Corp., another Shulsky interest and still the current owners. Description TEMPLE COURT BUILDING (For description of the Annex, see below.) The nine-story (ten stories in certain portions) building has facades on Beekman Street, Nassau Street, and Theatre Alley. Of fireproofed construction with iron floor beams, it was built around an interior skylighted atrium (now enclosed), with an additional exterior light well on the south side. It is clad in granite on the two-story base, and red Philadelphia brick (originally laid with red mortar), tan Dorchester stone trim, and terra-cotta panels on the upper stories. Much of the building, other than pans of the Theatre Alley facade, has been painted. Articulation on the facades on Beekman and Nassau Streets, as well as part of that on Theatre Alley, is similar, employing Queen Anne, neo-Grec, and Renaissance Revival motifs and ornamental details. The design is arranged horizontally into a base, midsection, and upper section (with mansard roof and towers), and in addition, it has a tripartite arrangement with end pavilions on each facade. The building is vertically expressed with continuous piers. Windows originally had one-over-one double-hung wood sash (some were double windows with a central mullion); most have been replaced by anodized aluminum windows with a variety of configurations. Base The two-story base is clad in granite, that on the piers rockfaced. Each story is capped by a cornice. Second-story windows in the center of the facades on Beekman and Nassau Streets are segmentally arched. All of the ground-story bays of the facades on Beekman and Nassau Streets (except the main entrance) have been converted to shopfronts over the years, and have been altered so that little historic fabric survives. Shopfronts are currently framed in metal, with rolldown gates. Base: Beekman Street The main entrance, located in the central bay, originally had polished red granite columns supporting an entablature bearing the name of the building, capped by an iron balustrade flanked by pinnacles; in 1949-50 the main entrance was altered with a polished marble surround, metal and glass doors, a transom, and the letters "5 Beekman." The bays flanking the entrance were originally windows; surviving below the cornice in each bay are a paneled band and decorative metal band. The end pavilions were originally tripartite, having a central door flanked by columns and windows with bulkheads and transoms; they were later altered to single bays with a bulkhead, display window, door, and broad sign band (since altered). The easternmost storefront is still framed by original fluted stone pilasters with stylized floral capitals. Base: Nassau Street End pavilion bays were originally tripartite, divided by piers. These bays, as well as those of the central section, had paired windows with bulkheads and transoms (the south end undoubtedly had an entrance door to the elevator hall); these bays were later altered in a manner similar to the pavilion bays of the Beekman Street facade (since altered). Surviving below the cornice in the south pavilion bay are a paneled band and decorative metal band. Base: Theatre Alley The northern section has articulation similar to that on Beekman Street. The ground and second stories of the center and southern sections are capped by stone bandcourses. The ground-story bays of these sections are divided by cast-iron piers and have transoms and ornamental iron bulkhead bands. All bays have been filled with cinderblock. The second-story bays of the center and southern sections are divided by cast-iron piers. Midsection The brick midsection consists of the third through the sixth stories. Articulation on the principal facades (and north pavilion of Theatre Alley) is similar, with terra-cotta spandrel panels above the third, fourth, and fifth stories; bandcourses, and stone capitals with a stylized floral design on the piers, on the third, fourth, and fifth stories; windows capped by round arches (with decorative tympana) in the center sections of the fifth story; and a stone cornice capping the sixth story. Most of the Theatre Alley facade is unadorned " Croton-faced" brick, with simple bluestone lintels and sills. Upper Section The upper section consists of the seventh through the tenth stories. The north section of the Theatre Alley facade has articulation similar to that on Beekman and Nassau Streets. The center portion of the two principal facades has paired windows with entablatures on the seventh story (the Theatre Alley facade is capped by a corbelled cornice on the seventh story), surmounted by, on each of the three facades, a two-story slate mansard roof with pedimented dormers (the upper dormers on Nassau Street, all dormers on Theatre Alley, and the flanking dormers on Beekman Street, are iron). The sections of roof on Beekman and Nassau Streets appear covered with asphalt. The end pavilions have bandcourses and terra-cotta spandrel panels above the seventh and eighth stories; round-arched windows, a subcornice, and cornice on the ninth story; a central pedimented window, and cornice with flared corner projections, on the tenth story of the northern pavilions; and a pediment on the tenth story of the southern pavilions (with a rondel on Nassau Street and corbelling on Theatre Alley). Roof Surviving decorative iron railings cap the mansard roof of the center section of each facade. Two prominent corner towers above the Beekman Street pavilions have octagonal pinnacled roofs, covered with slate and capped by metal finials. The corners of the pavilions are ornamented with pinnacles, and the inner side of each pavilion (except Theatre Alley) is flanked by a chimney. The southern pavilions have gable roofs. The center portion of the building is covered by a large pyramidal skylight with a monitor. - From the 1998 NYCLPC Landmark Designation Report |

|

|

links |

http://5beekmanstreet.com/ http://www.scoutingny.com/the-abandoned-palace-on-beekman-street/ http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/21/nyregion/21building.html?_r=0 |