|

New York

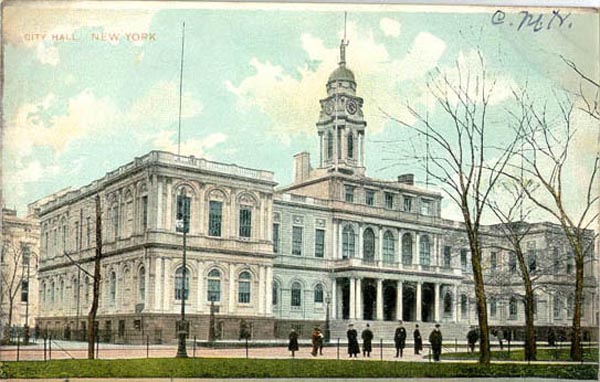

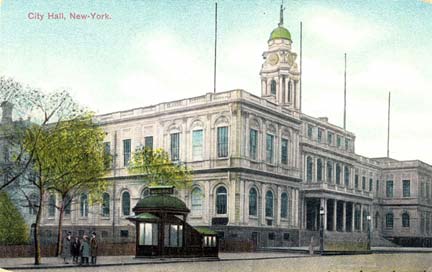

Architecture Images-Seaport and Civic Center City Hall (and City Hall Subway Station) Landmark |

||||||||||||||||||

|

architect |

Joseph Francois Mangin and John McComb, Jr. | ||||||||||||||||||

|

location |

City Hall Park (bet. Broadway and Park Row) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

date |

1803-1811 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

style |

exterior facade reflects that of the Renaissance Revival, and the interior that of the American-Georgian style | ||||||||||||||||||

|

construction |

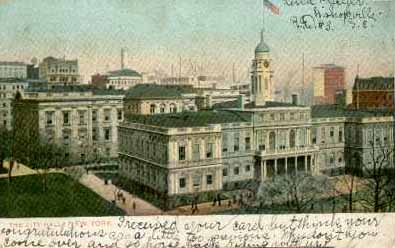

The building's front facade was formerly of white marble, while the back was brown sandstone. In 1954, the decay of the original material led to a replacement of the stonework of the entire facade with limestone above a pink granite basement level carved according to the original designs, and for the first time since its construction City Hall had four matching sides. | ||||||||||||||||||

|

type |

City Hall Government | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

.jpg) |

|||||||||||||||||||

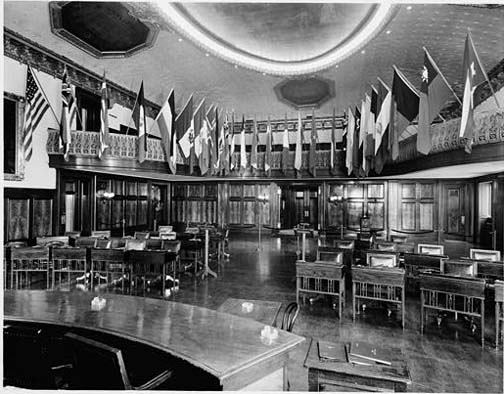

| The Governor's Room is used for official receptions. | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

.jpg) |

|||||||||||||||||||

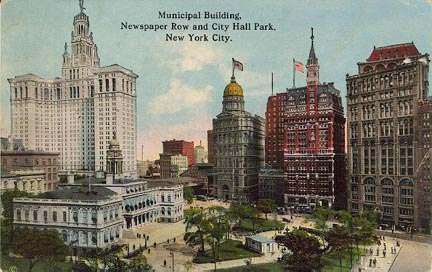

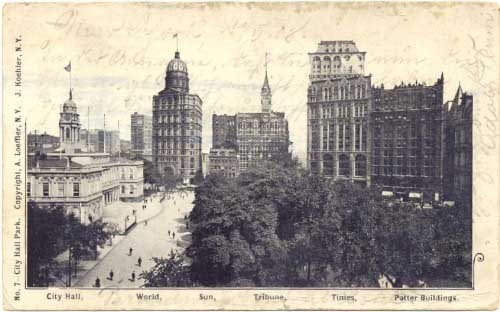

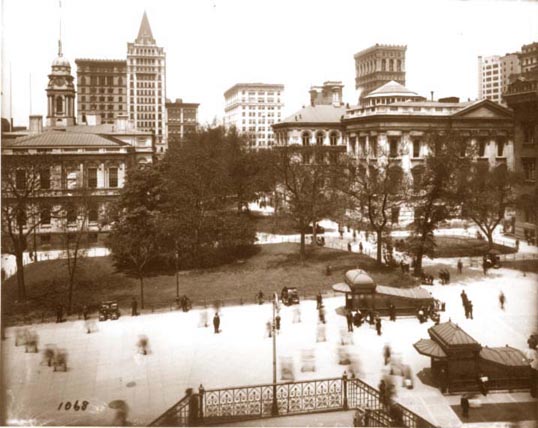

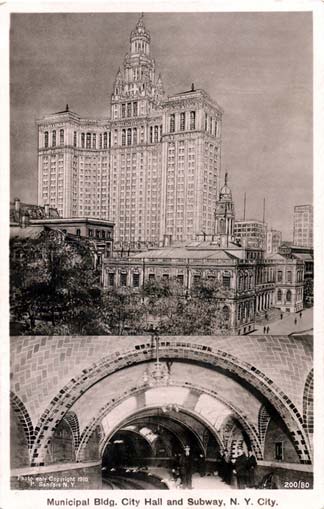

| City Hall Park panorama, circa 1911, with New York City Hall centered in the picture, with Mail Street (now closed) open to pedestrian traffic. The Mansard roof of the former Post Office building (demolished 1938) occupies the present site of City Hall Park on the left side of the picture. Behind City Hall is the Tweed Courthouse; to the right is the Municipal Building under construction, behind the Brooklyn Bridge Park Row elevated railway terminal. | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

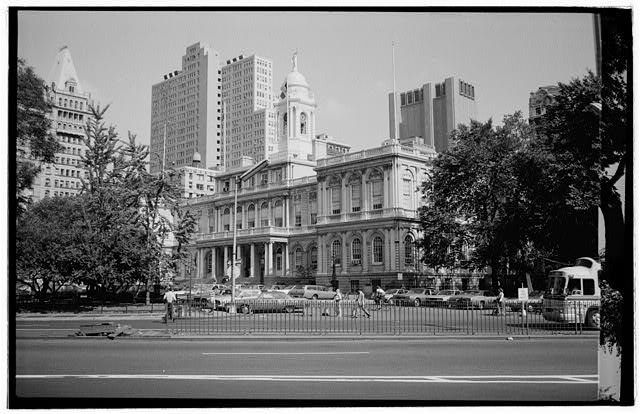

New York City Hall is the seat of the government of New York City. The

building houses the office of the Mayor of New York City and the

chambers of the New York City Council. The building is the oldest City Hall in the United States that still houses its original governmental functions. Constructed from 1803 to 1812, New York City Hall is a National Historic Landmark and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Its rotunda is a designated interior New York City landmark. City Hall is located within the small City Hall Park in Lower Manhattan between Broadway, Park Row and Chambers Street. Functions Official receptions are held in the Governor's room, which has hosted many dignitaries including the Marquis de Lafayette and Albert Einstein. The historic Blue Room is where New York City mayors have been giving official press conferences for decades and is often used for bill-signing ceremonies. Room 9 is the legendary press room at City Hall where reporters file stories in cramped quarters. While the Mayor's Office is in the building, the staff of thirteen municipal agencies under mayoral control are located in the nearby Manhattan Municipal Building, one of the largest government buildings in the world. The steps of City Hall are the frequent backdrop for political demonstrations and press conferences concerning city politics. Live, unedited coverage of events at City Hall is carried on NYCTV channel 74, a City government official cable television channel. Fencing surrounds the building's perimeter, with strong security presence by the New York City Police Department. Public access to the building is restricted to tours and to those with specific business appointments. History New York's first City Hall was built by the Dutch in the 17th century on Pearl Street. The city's second City Hall, built in 1700, stood on Wall and Nassau Streets. That building was renamed Federal Hall after New York became the first official capital of the United States after the Revolutionary War. Plans for building a new City Hall were discussed by the New York City Council as early as 1776, but the financial strains of the war delayed progress. The Council chose a site at the old Common at the northern limits of the City, now City Hall Park. In 1802 the City held a competition for a new City Hall. The first prize of $350 was awarded to John McComb Junior and Joseph Francois Mangin. McComb, whose father had worked on the old City Hall, was a New Yorker and designed Castle Clinton in Battery Park. Mangin studied architecture in his native France before becoming a New York City surveyor in 1795 and publishing an official map of the city in 1803. Mangin was also the architect of the landmark St. Patrick's Old Cathedral on Mulberry Street. Construction of the new City Hall was delayed after the City Council objected that the design was too extravagant. In response, McComb and Mangin reduced the size of the building and used brownstone at the rear of the building to lower costs (the brownstone, along with the original deteriorated Massachusetts marble facade, was replaced with Alabama limestone in 1954 to 1956). Labor disputes and an outbreak of yellow fever further slowed construction. The building was not dedicated until 1811. It officially opened in 1812. The building's Governor's Room hosted President-elect Abraham Lincoln in 1861, and his coffin was placed on the staircase landing across the rotunda when he lay in state in 1865 after his assassination. Ulysses S. Grant also was laid in state beneath the soaring rotunda dome. The Governor's Room, which is used for official receptions, also houses one of the most important collections of 19th century American portraiture and notable artifacts such as George Washington’s desk. On July 23, 2003 at 2:08 p.m., City Hall was the scene of a rare political assassination. Othniel Askew, a political rival of City Councilman James E. Davis, opened fire with a pistol from the balcony of the City Council chamber. Askew shot Davis twice, fatally wounding him. A police officer on the floor of the chamber then fatally shot Askew. Askew and Davis had entered the building together without passing through a metal detector, a courtesy extended to elected officials and their guests. As a result of the security breach Mayor Michael Bloomberg revised security policy to require that everyone entering the building pass through metal detectors without exception. Architecture The City Hall building epitomizes the American Federal style of architecture. The building's front facade was formerly of white marble, while the back was brown sandstone. In 1954, the decay of the original material led to a replacement of the stonework of the entire facade with limestone above a pink granite basement level carved according to the original designs, and for the first time since its construction City Hall had four matching sides. The building's distinctive cupola has served as a model for spires on other buildings, notably Eliot House at Harvard University. On the inside, the rotunda is a soaring space with a grand marble double stairway rising up to the second floor, where ten fluted Corinthian columns support the coffered dome. City Hall was formerly served by the City Hall subway station, a now-defunct station of the New York City Subway. The City Hall station was the southern terminus of the first tracks for the subway, which ran to 145th Street. The current City Hall Station is partly underneath the park. Portrait collection City Hall has a significant historical portrait collection. There are 108 paintings from the late 18th century through the 20th. The New York Times declared it "almost unrivaled as an ensemble, with several masterpieces." Among the collection is John Trumbull’s 1805 portrait of Alexander Hamilton, the source of the face on the U.S. $10 bill. There were significant efforts to restore the paintings in the 1920s and 1940s. In 2006 a new restoration campaign began for 47 paintings identified by the Art Commission as highest in priority. City Hall in popular culture New York City Hall has played a central role in several films and television series. Spin City (1996-2002), set in City Hall, starred Michael J. Fox as a Deputy Mayor making efforts to stop the dim-witted Mayor from embarrassing himself in front of the media and voters. City Hall (1996) starred Al Pacino as an idealistic Mayor and John Cusack as his Deputy Mayor, who leads an investigation with unexpectedly far-reaching consequences into the accidental shooting of a boy in New York. City Hall is also referenced in the folk song The Irish Rover as performed by The Pogues and The Dubliners: In the year of our Lord, eighteen hundred and six, We set sail from the Coal Quay of Cork We were sailing away with a cargo of bricks For the grand City Hall in New York Although the dates match those of City Hall, there is no recorded usage of Irish bricks in the building's construction. References ^ a b City Hall (New York). National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service (2007-09-10). ^ National Register Information System. National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service (2006-03-15). ^ ["New York City Hall", by Charles E. Shedd, Jr. (includes figures)PDF (429 KiB) National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings]. National Park Service (1959-10-28). ^ Killer Competition: Activist and councilman James Davis played his own brand of Brooklyn-style political hardball. But Othniel Askew threw out the rule book., New York Magazine, August 4, 2003 ^ New York City Transit - History and Chronology, accessed December 28, 2007 ^ "In New York, Taking Years Off the Old, Famous Faces Adorning City Hall.", The New York Times, December 6, 2006. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

City Hall has been the seat of New York City government since 1812. Located in City Hall Park at the southern end of the Civic Center, City Hall is one of the most treasured buildings in the City. In the 17th century, the Dutch City Hall was in the old City Tavern on Pearl Street. A new City Hall was built in 1700 at Wall and Nassau Streets. It was renamed Federal Hall when New York became the first capital of the United States. The 1833-1842 Federal Hall National Memorial is now on this site. The Common Council talked about a new City hall as early as 1776 but the Revolutionary War intervened. A site was chosen, the old Common at the northern limits of the City, now City Hall Park. In 1802, a competition was held for the new City Hall and twenty-six proposals were submitted. First prize of $350 was awarded to John McComb, Jr. and Joseph Francois Mangin. John McComb's father repaired the old City Hall in 1784. John McComb, Jr. was a New Yorker while Joseph Mangin was trained in his native France. McComb designed the landmark Hamilton Grange on Convent Avenue, Castel Clinton in Battery Park and the James Watson House on State Street. Joseph Mangin was City Surveyor in 1795 and published an official City map with Casimir Goerck in 1803. He designed the landmark Old St. Patrick's Church on Mott Street. City Hall is the only known project the two architects collaborated on together. Construction was delayed until 1803 due to objections by the Common Council that the design was too expensive. The size of the building was reduced and brownstone was used on the rear to keep costs down. Construction moved slowly due to labor disputes and a Yellow Fever outbreak. Workmen earned one to one and one half dollars a day. The building was dedicated in 1811 but did not open until 1812.

On the inside, the rotunda is a soaring space with a grand marble stairway rising up to the second floor, where ten fluted Corinthian columns support the coffered dome. The rotunda has been the site of municipal as well as national events. Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant were laid in state here, attracting enormous crowds to pay their respects.

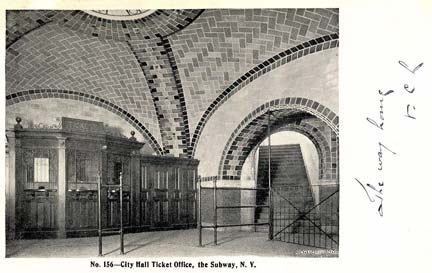

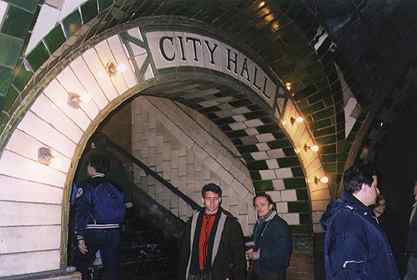

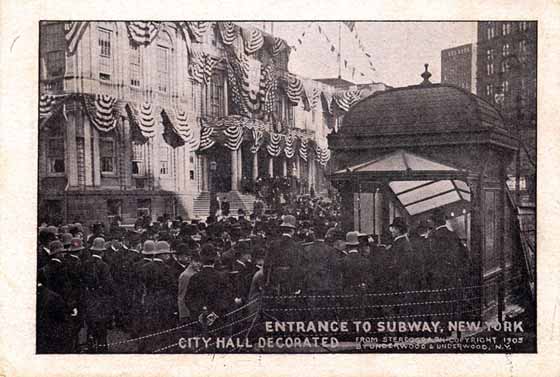

THE CITY HALL STATION was the showpiece of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company. Having been described as the most beautiful subway station in the world, this "apotheosis of curves," as House and Garden magazine termed it, was meant as a way to show off the splendor and glamour of New York's first subway line; of course, it is like no other subway station. From the moment the train curves into the station, it is obvious that this place is different. Perhaps its most stunning features are the Guastavino arches, which were also used by architects Heins and LaFarge at one of their other great monuments, the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine; there is not a straight line or support column in sight. The station is alive with color, with natural light from the vault lighting in front of City Hall upstairs pouring into the station, through the three leaded glass sections above the tracks, and the oculus atop the mezzanine. ALAS, City Hall Station succumbed to its unique design. After 41 years, City Hall saw its last day of passenger service on December 31, 1945. While most of the other original stations had been lengthened to accommodate longer trains, it was not deemed worthwhile to extend City Hall, with Brooklyn Bridge station so close by. Indeed, no extension of City Hall could match the architectural beauty of the original. THE FOLLOWING PHOTOGRAPHS document the construction of City Hall station, from 1902 right until opening day of the IRT on October 27, 1904.

AFTER FOUR AND ONE HALF YEARS

of construction, New York finally had

its subway system. It was indeed a great marvel, and the showcase of it

all was right below New York's seat of government and power. All the

dignitaries streaming out of City Hall could indeed be proud of their

city's accomplishment. SO MORE THAN 90 YEARS after the subway opened, and more than 50 years after City Hall Station closed to the public, what is this great station like today? Trains still pass through everyday; after the doors have closed and the conductor has said "Last Stop" on the downtown 6 train at Brooklyn Bridge, the train loops through City Hall to return back to the uptown tracks. Passengers are now allowed to stay on the train and go around the loop (the conductor sometimes even says, "Next Stop, Brooklyn Bridge Uptown"). So you, too, can see City Hall. If you want more than a brief glimpse of the station, the Transit Museum sponsors several tours each year of City Hall; you actually get off the train at the station, and can walk around for about 20 minutes. The noise from the passing trains is quite loud, but it is not enough to deter from the wonder of the station. It is in remarkably good shape for an original IRT station; natural light even pours through the one remaining surface vault lighting slab, forming interesting patterns on the platform. CURRENT PLANS CALL FOR the station to be reopened as an annex of the Transit Museum. Three semicircular plaques that fit in the arches along the inner station walls, that were moved to Brooklyn Bridge station when City Hall was closed, have been returned to their original location. City Hall may never see a fare paying passenger again, but soon the public will get to experience the great pride and accomplishment the IRT planners found in their subway. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

links |

|||||||||||||||||||