|

At first sight, the Hotel Pierre gives the

impression of a nicely detailed finishing Seventeen Century Mansard

shooting pavilion that suddenly would have grown from the ground to a

503 feet height. Though finished during the Great Depression eve, the

Pierre easily gained fashionable notoriety partly due to the neighboring

of three prestigious hotels previously built: the Plaza, the

Sherry-Netherland and the Savoy (replaced by the ugly General Motors

Bldg). Excepted the upper french pavilion with its steeply sloped

copper-clad roof, the main body of the building is not particularly

remarkable: a three-stage platform, a series of setbacks surmounted by a

tower from which the elevators partly blind the south façade. The first

two floors are more interesting with their intrically modeled spaces

leaded by three different entries.

In "Fifth Avenue, A Very Social History,"

published in 1978 by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Inc., Kate Simon recounts

some of the Pierre Hotel's early history:

"Ambitious and tenacious, like many of his fellow Corsicans, Charles

Pierre Casalesco left his father's Ajaccio restaurant where he had been

the busboy, to go as Charles Pierre to the brilliant Hotel Anglais in

Monte Carlo....On a job foray to London, he was picked out by Louis

Sherry for a position in New York. Twelve years of Sherry's brought him

to an impasse. Smart women were beginning to smoke in public rooms. Mr.

Sherry forbade it in his restaurant, an irritating, old-fashioned

prohibition, Pierre thought, and, after flights of heated words he left.

A stint then at the Ritz-Carlton on Madison Avenue at Forty-sixth,

followed by his own restaurant, first on Forty-fifth immediately west of

Fifth Avenue, and later at 230 Park, a place equally famous for its

cuisine and for its care of American heiresses who, it was seen to by M.

Pierre (himself occasionally the escort) went directly home to Mama.

Inevitably he became a conservative elder statesman, deploring the vast

democratic size of World War I parties and the unrestrained Prohibition

guzzling that followed after. He soldiered on in this frantic new world

that had lost its manners until a group of admirers and financiers,

among them Otto H. Kahn, Finley J. Shepherd (who had married Helen

Gould), Edward F. Hutton, Walter P. Chrysler, Robert Livingston Gerry

(the son of Elbridge Thomas Gerry, lawyer, philanthropist and grandson

of Elbridge Gerry, the inventor of 'gerrymandering') and others decided

to use the site of the Gerry mansion at Sixty-first Street and Fifth

Avenue for a hotel to be managed and run by Charles Pierre. The new

structure, rising forty-two stories, could hardly keep the Richard Hunt

chateau quality of the pink mansion it replaced, but a few old France

touches were built into the hotel whose motto was 'from this place hope

beams.'"

The Depression took its toll, however, and the hotel went into bankruptcy

in 1932. Six years later, oilman J. Paul Getty bought it for about $2.5

million in 1938 and subsequently sold many cooperative apartments in the

building. The hotel's operations changed hands a few times until Trust

Houses Forte Corporation took it over in 1973 and finally the Four

Seasons luxury hotel chain in 1986.

(Having sold his townhouse for the new hotel, Elbridge T. Gerry bought a

Georgian-style townhouse on the northeast corner of Fifth Avenue and

94th Street from Mrs. Leonard K. Elmhirst, who, according to Robert A.

M. Stern, Gregory Gilmartin and Thomas Mellins in their book, "New York

1930, Architecture and Urbanism Between the Two World Wars," published

in 1988 by Rizzoli, "stipulated that it not be demolished. Mrs. Elmhirst

was Dorothy Payne Whitney Strait, one of the country's leading

heiresses, suffragettes and a founder of the Junior League whose first

husband, Willard Strait, had founded The New Republic magazine. She and

her late husband, Mr. Elmhirst founded and operated Dartington Hall, a

very progressive school and cultural center in England.)

In 1988, the hotel's duplex penthouse, shown at the left, with an enormous

ballroom with double-height arched windows, was put on the market with

the highest price tag ever believed then asked for a single co-op - $20

million. A couple years later, it was sold to Lady Fairfax for about $12

million, who was reported to have sold it in 1998 by The New York

Observer for more than $20 million.

The ballroom, which had served for a while as a supper club, had been

rented for parties over the years had long been not in use as the hotel

had redone its main public spaces in its base where it had another

ballroom as well as a circular double-height lounge with a painted mural

that included a portrait of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

The penthouse ballroom, with views in all directions, large mirrors etched

with palm trees, a small bandstand and some peeling pink paint when it

was offered in 1988, can hold 285 people at once, according to a Fire

Department sign that then hung on a wall. It had not been used as a

ballroom since 1973. A hotel employee said that the views from its

corner terraces were so grand that they had been used as lookouts by the

Police Department. The views, in fact, from its terraces are grand. In

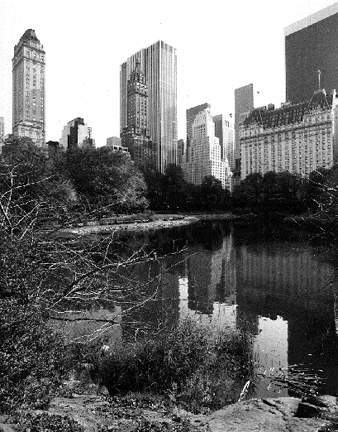

1994, the building, shown at the right above in a view from 59th Street,

announced it would have to replace its three-story-high copper roof, but

since the building is within the Upper East Side Historic District and

therefore a landmark the new roof will not alter the hotel's appearance.

The hotel originally had 714 guest rooms, but many of them were combined

into larger suites over the years.

The Pierre Hotel's Fifth Avenue entrance, under a white and gold canopy,

is very disappointing as the main entrance is really on the sidestreet.

The Fifth Avenue entrance leads up a few stairs to the elevator bank and

also has stairs leading down to a restaurant. A pleasant window-less,

street-level cafe has its own Fifth Avenue entrance. The main sidestreet

entrance opens onto a pleasant, but low-ceiled lobby and raised alcove,

but is rather restrained and not spectacular, similar to the lobby

treatment at the Carlyle Hotel on Madison Avenue at 76th Street.

The hotel's tower was marred somewhat by repairs to its corners over the

years and much of its south facade is blank because of the placement of

the elevator bank.

|