|

New York

Architecture Images-Upper East Side Seventh Regiment Armory Landmark |

|

architect |

Charles W. Clinton |

|

location |

640 Park Ave., Bet. East 66th & East 67th. |

|

date |

1877-79 |

|

style |

|

|

construction |

red brick, limestone trim |

|

type |

Government Armory |

|

|

|

|

|

|

images |

|

|

|

|

|

The Park Avenue facade of the Seventh Regiment Armory evokes the fortified palazzi of north Italian city-states from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The proportions of the three square towers (the central tower was originally topped by a two-story open bell tower) as well as the insistently flat surfaces of pressed red brick and granite trim mark the building as a High Victorian production. The entryway of bronze gates and six-inch thick oak doors with musket ports is large enough to allow a four abrest formation to march in and out of the building. The architect was Charles W. Clinton, a veteran of the Regiment and a student of Richard Upjohn, and the premier Gothic revivalist in the United States. Clinton’s later work, executed in partnership with William Hamilton Russell, centered on skyscraper design influenced to a certain degree by the Chicago architect Louis Sullivan. This is the only armory in the United States to be built and furnished with private funds. The interior is distinguished by two features; a large drill floor, covered by an impressive iron roof, and the lavish Veteran’s Room and adjoining library (known today as the Trophy Room), designed by a group of artists working under the direction of Louis Comfort Tiffany. Other designers who contributed to the building included the Herter Brothers, Alexander Roux, Pottier & Stymus, Kimbel & Cabus, and Marcotte & Company. In 1909, a floor was added to the administration area; in 1930 a fifth floor was added and the third and fourth floors were redone. The first and second floors, however, are unchanged. A landscaped areaway behind a low railing surrounds the building on all but the Lexington Avenue side. The Armory is a National Historic Landmark. The Seventh Regiment was formed in 1806. It has a long list of battle honors (including service in the War of 1812, The Civil War, and both World Wars). During public disturbances (such as the civil riots of the 1830s and 40s) the Regiment controlled and subdued civilian crowds and protected private and city property from looting and vandalism. For a complete history of the Seventh Regiment see our historical article titled "The 7th NY and the Naming of the National Guard" New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs |

|

|

Andrew S. Dolkart, "Touring The Upper East

Side, Walks in Five Historic Districts" (published by the New York Landmarks Conservancy, 1995): "Charles Clinton, a veteran of the Seventh, designed what is generally considered to be the prototype model for the urban armory - a medieval-inspired administration building set in front of a large drill shed. The massive brick administration building, with its heavy base and mock-fortress features - such as crenellations and slits for crossbow arrows - is an imaginative structure borrowing elements from various medieval styles. The arched drill hall is supported by iron trusses resembling those of contemporary railroad station sheds. Urban armories not only served as drillhalls for volunteer militia, but were also primate men's clubs with appropriately elaborate interior decor. No regiment was more exclusive than the Seventh, known as the 'silk stocking' regiment, and the interiors of its armory reflect that status. The armory contains some of the finest surviving 19th Century rooms in America, including the Veteran's Room and Library (now the Trophy Room), which were the earliest major commissions of the Associated Artists, the decorated firm established by Louis Comfort Tiffany. Other rooms were decorated by Alexander Roux Co., L. Marcotte Co., Herter Brothers, and Pottier Stymus, all leading American decorating firms. The armory was endangered in 1980-81 by an imprudent plan to construct a highrise luxury hotel or apartment building above the drill hall and, more recently, by proposals to mar the interiors with exposed sprinklers. A preservation campaign spearheaded by the Friends of the Armory was successful in gaining landmark designation for much of the interior in 1994." James Trager, "Park Avenue, Street of Dreams" (Atheneum, 1900), "The 7th Regiment, formed in 1806, had served in the war of 1812 and had gained some powerful friends by its performance in the Astor Place riots of 1847. It was unified in 1860 at the newly built Tomkins Market Armory, on the east side of the Bowery between 6th and 7th Streets, and played an important part at the outset of the Civl War, protecting the nation's capital when it was cut off by rebel forces in Maryland. Its members included included a number of socially prominent New Yorkers, and its spelendid new armory....is the nation's only armory built and furnished with private funds....Youngsters enrolled in the very social Knickerbocker greys exercised twice each week under the iron roof of the great drill hall. Today the armory is home to the 2nd Brigade, 42nd Infantry Division, and the 1st Batallion, 107th Infanty, New York Army National Guard." |

|

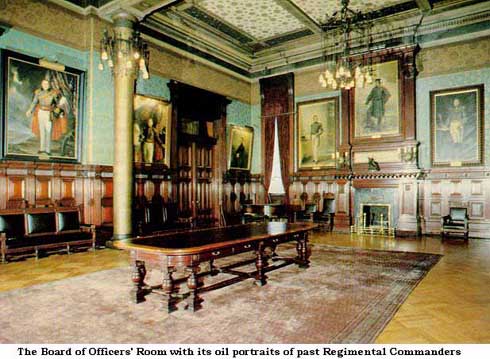

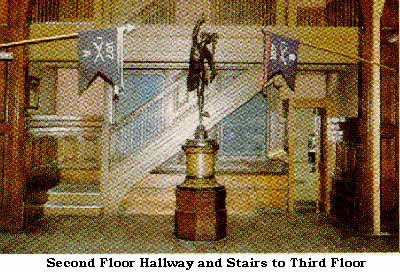

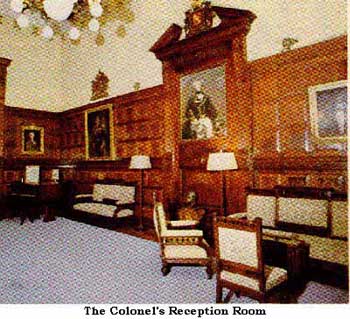

| The Seventh Regiment Armory in

New York City - restoration of the historic site in New York Magazine Antiques, Jan, 1999 by Mary Anne Hunting On January 15 the Forty-fifth Annual Winter Antiques Show will open at the Seventh Regiment Armory, which occupies the block between Sixty-sixth and Sixty-seventh Streets on Park Avenue in New York City. The show is one of many events that have drawn thousands of visitors into the magnificent fifty-four thousand square foot Drill Room since 1879. However, many visitors are probably unaware of the significance of this monolithic building - a prototype for hundreds of armories across the United States.(1) Distinguished by its functional design and architecture, the armory is also celebrated for the splendor of the decorations executed by some of the most talented artisans of the day, its collections of decorative and fine arts, and its history, which is a testament to the Seventh Regiment and the community it served until 1947.(2) Although this landmarked building is now sadly in poor condition, it is still the military palace that forty thousand subscribers lined up to see when it officially opened its massive doors in 1880.(6) The Seventh Regiment, known as the silk stocking regiment for its prestigious roster of members, was the largest and most admired volunteer militia in the country during the nineteenth century. Its nucleus was formed in 1806 after British frigates, blockading New York Harbor, fired at passing vessels that resisted a search for British deserters, and in so doing killed an American helmsmen. The first four companies of artillery in what became the Seventh Regiment were created by volunteers after a mass rally called for reprisals for this death. It was given the name Seventh Regiment, National Guard, State of New York, in 1847. New York City came to depend on this militia, which was regularly called on to quell civil disorders such as the Astor Place Riot of 1849 when it dispersed a mob of twenty thousand, driving away "the bleeding rioters, demoralized and defeated, from the streets".(6) It also helped fight large fires and took part in protecting citizens and businesses. The Seventh Regiment participated in important events, such as the inaugurations of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883 and the Statue of Liberty in 1886, as well as other civic ceremonies such as receiving the remains of President Lincoln upon their arrival in this city, guarding them at the City Hall, and of acting as the special escort and guard of honor in the great and memorable demonstration upon their removal from the city.(7) The Seventh Regiment's first home, shared with a public market, was in the Italianate cast-iron Tompkins Market completed in 1860 on the lower East Side. However, by 1868 it was apparent that the regiment needed to be in a neighborhood more convenient to its members as well as the population it protected, which was migrating north. In addition to a large hall in which to drill and ample storage for arms and ammunition, the members wanted a ceremonial setting in which to impress recruits with the regiment's glorious past. The armory also functioned much like men's clubs of New York and London, which served social and sometimes business purposes. The first effort to obtain a site at Reservoir square (now Bryant Park) was opposed by neighbors who feared the devaluation of their real estate. In 1875 the city appropriated a lot for the armory on Fourth Avenue (renamed Park Avenue in 1881). The regimental Board of Officers had originally anticipated that the city would contribute $350,000 for the new building, but partly owing to a lasting depression, this did not materialize. The regiment realized it had to make an earnest effort to build the necessary armor by subscriptions from the active and veteran members of the Regiment, and from the liberal citizens, business men, and tax-payers of the city of New York.(8) Donations poured in not only from such prominent New Yorkers as John Jacob Astor, William H. Vanderbilt, E Augustus Schermerhorn, William C. Rhinelander, and James Lenox, but also from the growing middle class, which saw an opportunity to invest in its protection from civil strife. About $90,000 was raised from members of the regiment, $27,000 from veterans, $86,000 from the community, $33,000 from businesses, and $151,000 from a bond issue. This was enough to raise the building but not to furnish it.(9) In April 1879, when the shell of the armory was nearing completion, a committee of members and veterans began organizing a spectacular, two-week-long fair to raise money for the decoration of the building. Opened by President Rutherford B. Hayes on November 17, 1879, the fair was eventually extended for a third week The focal point in the lavishly decorated Drill Room was a central forty-foot hexagonal arbor festooned with flowers, vines, evergreens, and moss. The surrounding booths, designed by each of the ten companies in the regiment, composed what one contemporary called a "tournament of taste to which the companies of the regiment have challenged each other."(10) There were temples, pavilions, gateways, tents, and marquees of Byzantine, Moorish, Chinese, Venetian, Persian, Egyptian, English Gothic, Queen Anne, and even English military inspiration. A vast array of expensive goods was offered for sale, including carriages, boats, organs, jewelry, safes, even Angora cats and fox terriers.(11) Competition among the companies was fierce to realize the largest profit and thereby win the silver punch bowl offered by Brooks Brothers, the maker of the regimental uniforms. The fair also provided a variety of entertainments, which included ventriloquists, shooting galleries, magic shows, gypsy fortune-tellers, Punch and Judy shows, an exhibition of nearly two hundred European and American paintings and prints from private collections, and an exhibition of yacht models from the New York Yacht Club. There was a grocery store, Moses' Turkish Bazaar, a tobacco room, toy store, candy store, Old Curiosity Shop, and Oriental Tea Room. As the attractions varied each day, it behooved visitors to rerum frequently - and they did. The New York Times reported: A peculiarity of the Seventh-Regiment New Armory Fair is that every day the crowd is larger, more enthusiastic, and more liberal in their purchases, and more reckless in their patronage of prize drawings than on any preceding day.(12) The fair raised $140,550 - the equivalent of $2.2 million today.(13) Harpers Weekly reported that such "extraordinary results" were "evidence of the high place which the Seventh Regiment now holds in the hearts of the people of New York."(14) The armory was designed by the New York architect Charles William Clinton under the close supervision of Colonel Emmons Clark (1827-1905), the regiment's commander from 1864 to 1889. Clinton too was a member of the regiment and had created four company rooms in the Tompkins Market Armory. His design for the Park Avenue armory is riotously eclectic, with romantic, exotic, and purely military elements, and an emphasis on castellation. Strong, dignified, and impenetrable, the armory became increasingly medieval as plans progressed, despite the Second Empire mansard roof. Originally three stories high, the classically proportioned front facade was dominated by a slender central tower flanked by two stabilizing turrets capped with battlements. The base of the building is rusticated granite on which rest two-foot-thick walls of Philadelphia pressed brick accented with horizontal bands, sill courses, and quoins of granite. The entrance in the base of the central tower - with six-inch-thick oak doors wide enough to admit four men marching abreast - is protected by an immense bronze gate made by Mitchell, Vance and Company (1860-1933) of New York City, that is topped by the regiment's coat of arms. Sadly, much of the original monumentality was lost during a restoration begun in 1909. A fourth floor was inserted into the mansard roof, and the slender top of the central tower was removed, to be replaced by the present crenellations (see Pl. II). The roof line was altered again in 1931 when a fifth floor was added. Taking inspiration from the architecture of railroad terminals, where the train shed extends behind the terminal building, the architect planned for two buildings joined: the Administrative Building and the Drill Room. Clinton's specific inspiration was Grand Central Depot in New York City, which was built between 1869 and 1871. Its train shed, at the time the largest unobstructed interior in the United States,(15) was supported by a wrought-iron truss system engineered by Robert Griffith Hatfield (1815-1879), who also served as a consultant on the Drill Room, which was developed by Charles Macdonald (1837-1928), the president of the Delaware Bridge Company. The so-called balloon-shed construction consists of a vault supported by eleven wrought-iron arched trusses, each spanning 187 feet from side to side. The building is reinforced by masonry buttresses. The Drill Room was one of the first privately built structures in the United States to use iron trusses, and it is today the oldest extant building of this kind in the country.(16) The original floor of the Drill Room survives despite extraordinarily heavy use by spectators, marching men, automobiles, and Army tanks. It is made of thick, narrow planks of Georgia pine set on sleepers of Long Island locust embedded in asphalt, which rests on a platform of concrete. Light was provided by two stories of clerestory windows running the length of the room as well as a number of windows hi the north and south walls that were filled in during renovations between 1911 and 1913. There were originally also gas chandeliers with porcelain reflectors to light the huge room at night. George C. Flint and Company of New York City provided black walnut cases for the regiments Remington rifles along the west end of the room. Seating for about eleven hundred people was provided on ash settees with mahogany backs in the galleries on the east and west ends and on raised platforms lining the perimeter at ground level.(17) The room was the scene not only of drills by the regiment but also by the Knickerbocker Greys, a boys' drill school founded in 1881. As intended from the beginning, it has also been used for many community functions such as music festivals, tennis tournaments, grand balls, and art fairs. In September 1998 it even served as a place of worship when part of the nearby Central Synagogue burned. A fascinating and forgotten feature of the Drill Room is the original painted decoration designed by the Hudson River school painter Jasper F. Cropsey and executed by John Sulesky (see Pl. V).(18) The painting was begun before the art fair and long before most other interior decorative schemes had been planned. Cropsey's elaborate specifications survive for paint, stain, and other decorative treatments for the walls, pine rafters, lantern, trusses, balconies, and window frames of the room.(19) They include fourteen full-scale paper stencils and drawings depicting stylized stars, shields, floral and foliate designs (see Pls. VI, VII), as well as the coat of arms of 1835 that was painted above the third-floor balcony on the western wall.(20) Some people thought the decoration of the Drill Room was too complicated and not in keeping with the propose of the room, while others felt that the bright and lively designs helped alleviate the monotony of the architecture.(21) In any event, Daniel Appleton (1852-1929), who was colonel of the Seventh Regiment from 1889 to 1920, complained in 1897 of the "'lager beer saloon' effect" of the decoration,(22) and it was painted over during his administration. There are fourteen rooms on the first floor of the armory that Kevin Stayton, the curator of decorative arts at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in Brooklyn, New York, has declared "are the single most important collection of nineteenth-century interiors to survive intact in one building...[and] form a large and critical part of the foundation of our understanding of the an of this em."(23) They represent the work of the most prestigious interior decorating firms of the day: A. Kimbel and J. Cabus, L. Marcotte and Company, Pottier and Stymus Manufacturing Company, Roux and Company, George C. Flint and Company, Herter Brothers, and Associated Artists. As fine as the most elegant interiors of private clubs and the most ornate residences in New York City, the armory interiors are among the few of this stature to survive.(24) George C. Flint and Company decorated the severe and dignified entrance hall [ILLUSTRATION FOR FIGURE 2 OMITTED], the corridors on the first and second floors, and the Company A Room.(25) The central feature of the entrance hall is the monumental split staircase made of wrought iron sheathed in oak, which also panels the walls. The pair of bronze torcheres at the base of the stairs was made by Mitchell, Vance and Company Originally gaslit, they are among the few in the armory that were converted to electricity rather than replaced in 1897 with wrought-iron fixtures supplied by the John L. Gaumer Company of Philadelphia. The Field and Staff Room (Pl. XI), also in the Renaissance-revival style, was originally furnished by Pottier and Stymus, the firm that decorated the rooms belonging to Companies D, E, G, and I. This firm also supplied the woodwork in two regimental rooms on the second floor. Originally elaborately stenciled on the walls and ceiling, the Field and Staff Room has undergone substantial changes. Between 1895 and 1898 additional mahogany lockers were built and the wainscoting was extended, and in 1933 it was "completely redecorated and partly refurnished" by the A. H. Davenport Company.(26) Herter Brothers of New York City decorated eight rooms in the armory: the Board of Officers' Room, Reception Room, Colonel's Room, Non-Commissioned Staff Room, Memorial Room (and its conversion into the Library in 1895), Company C Room, Company H Room, and, in 1895, the Quartermasters Room. Under the sole artistic direction of Christian Herter (1839-1883) from 1870 to 1883, it was the most prolific decorating firm of the Gilded Age and championed the principles of the American aesthetic movement. Christian Herter's decorative vocabulary of two-dimensional designs of abstract floral and geometric motifs covering nearly every surface owed much to his English predecessors Owen Jones, Christopher Dresser, and Charles Locke Eastlake, among others. The Board of Officers' Room (Pl. X) is today the least altered of the Herter rooms at the armory because in 1932, when it was renovated, A. H. Davenport Company was asked to simply repaint the stenciling in an effort to maintain the original intent in honor of Emmons Clark, to whom the renovated room was dedicated. As a result of this "interesting (and early) instance" of historic preservation, Jay Shockley wrote in his most impressive designation report for the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, the room is "of supreme importance as one of the very few surviving interiors designed by Herter Brothers in the United States."(27) Although it is now in poor condition, a photograph taken in 1981 shows the remarkable stenciling and Renaissance revival mahogany woodwork, also by Herter Brothers. The curator of the Seventh Regiment Fund, Paul B. Haydon, who wrote his master's thesis on the Herter Brothers rooms at the armory, had this to say: The "frescoed" ceiling in the Board of Officers' Room is nothing less than spectacular. It is divided with bandings of different flowers, repeating those found in the main field and frieze, while also including the "passion" flower, horse chestnuts, and other flora that were wildly popular throughout the aesthetic period....testament not only to the laudable design capabilities of Herter Brothers, but to their excellence in execution as well.(28) The portrait of George Washington by Rembrandt Peale that originally hung over the fireplace in the Board of Officers' Room was moved to the Colonel's Room (see Pl. XII) during a renovation of that room by Davenport between 1932 and 1947, at which time the French black walnut overmantel there was reworked to receive the painting. The portrait was given to the Seventh Regiment by four prominent New Yorkers in 1861. The Herter Brothers rooms at the armory are still largely overshadowed by the two rooms decorated by Louis Comfort Tiffany and the firm Associated Artists: the Veterans' Room (frontispiece and Pls. I, XIV) and the Library (Pls. m, IV). They were at least three times more expensive than the Herter rooms.(29) Associated Artists, founded in 1879, was a collaboration between Louis Comfort Tiffany, the son of the founder of Tiffany and Company, the textile designer Candace Thurber Wheeler, the Hudson River school painter and decorator Samuel Colman, and the ornamental woodcarver Lockwood de Forest. The firm, which gave the aesthetic movement an American cast, was convinced that the most beautiful and harmonious interiors are the result of the close collaboration of many hands. For the armory rooms, Colman provided the subtle color harmonies and decorative stenciling, de Forest the wood carving, Wheeler the embroidered hangings, and Tiffany the colored-glass tries and windows. The young Stanford White (of the firm McKim, Mead and White) was a consultant on the architectural composition, including the built-in furniture, fireplaces, latticework, and inset panels on the wainscoting of the Veterans' Room. Francis Davis Millet and George Henry Yewell researched and painted the decorative frieze, and it is thought that Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848-1907) and David Maitland Armstrong (1836-1918) may also have worked on the room.(30) But it was Tiffany who provided the synthesis. As Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, has noted, "His was not an intellectual approach to his art; rather it was a sensory one, providing a visual feast of color, light, and texture."(31) The Veterans' Room and Library represent an amalgamation of decorative ideas described in 1885 as "Greek, Moresque, and Celtic, with a dash of the Egyptian, the Persian and the Japanese."(32) In keeping with the theme of military triumph, the frieze around the top of the Veterans' Room (Pl. XIV) painted by Yewell and Millet presents a progression of twenty cultures and twenty battles from the Stone Age to the Civil War. The wainscoting incorporates a band of grotesque carvings of fire-breathing dragons in the Celtic or Old Saxon style, and stained-iron plaques with studs originally picked out in silver resemble rested plates of armor. The doors leading to the Library have details that mimic hammered and studded shields, and the two large columns in the Veterans' Room (see Pl. XIV) are wrapped with evocations of chain marl. The elaborate wrought-iron radiator covers, candelabra, and chandeliers also evoke weapons and defense. Among the innovative details are the wallpaper printing rollers that top the columns supporting the elaborately carved mantel (see frontispiece and Pl. I). Printing cylinders are also used as the legs of the oak table, while printing blocks are set into the chairbacks. The painted plaster overmantel of an eagle swooping down on an agitated snake is made from molten glass, a metal conduit, a glass eye used in taxidermy, and the bottom of a champagne bottle - the sort of recycling that Tiffany frequently favored.(33) The coffered wood ceiling (see Pls. I, XIV), symmetrically divided into squares, has designs resembling chain marl stenciled in aluminum foil - then a novel material as expensive as gold, according to Haydon. The focal point of the Veterans' Room is the fireplace wall, which is pure Tiffany. The intense peacock-blue glass blocks above the fireplace opening illuminate the surrounding architecture and dramatically draw attention to the light. Nanking the fireplace are two of the five Tiffany stained-glass windows in the room, which, Frelinghuysen claims, "reveal an abstraction found in stained glass virtually for the first time."(34) On the wall to the left of the fireplace an intricately detailed lattice screen encloses a balcony reminiscent of one in a harem.(35) The walls between the wainscoting and the freize were once covered with a blue-gray wallpaper (of which a fragment survives) that is hand stenciled in silver and copper leaf with designs that resemble the chain-mail motif at the top of the large columns. The curtains and portieres designed by Wheeler are also gone, although the details of the portieres are known through a photograph of 1884. The portieres were made of Japanese brocade bordered with plush simulating leopard skin. The central design consisted of velvet appliques depicting the "days of Knighthood and romantic warfare."(36) Overlapping steel rings sewn onto the hangings resemble chain mail. The veterans of the regiment were given exclusive control of this room until 1889, while the adjoining Library was always intended for both veterans and active members of the regiment. A brochure written by the veterans in 1881 describes the relationship of the two rooms: The Library...is but a barrier of books, over which the younger men may look across in to the Elysium which awaits them when they shall become Veterans, and into which the Veterans may look back with fatherly interest upon the studious young militants, who are ripening for the time when they, too, will "Shoulder the crutch/And show how fields were won."(37) The Library was designed to hold two thousand books, but within fifteen years it was turned into a regimental museum, in which the silver, trophies, and other plate are now stored. The central feature of the room is a magnificent cast-plaster basketwork vaulted ceiling embellished with decoration that was originally painted salmon and dotted with medallions once covered with silver leaf. Before glass doors were added between 1911 and 1914, the bookcases on the ground level were enclosed by iron gates and chain-link portieres, while the ones around the gallery had curtains. The iron railing surrounding the gallery is decorated with a weblike pattern in copper. The marvelous chain-link chandelier and four wall fixtures were made by Mitchell, Vance and Company, probably to the specifications of Associated Artists. Only one of the two staircases to the gallery survives, but it retains its mahogany lattice screen and iron gate (Pl. IV). The gallery walls on the east and west were once stenciled. The latter still retains its abstract stained-glass window designed by Tiffany. Since their inception the Associated Artists' rooms have been treasured for their originality, craftsmanship, and exquisite decorative detail. In the 1880s the Veterans' Room was called "the most magnificent apartment of the kind in this country,"(38) and a century later it was called "a major achievement of its era."(39) However, in 1881 the critic William Crary Brownell (1851-1928) wrote in Scribner's Monthly that he objected to the "whimsical subtlety" of the imagery, claiming that "a similar spirit would decorate the exterior of a post-office with letter-boxes, or cover the walls of a bedroom with pictures of towels and tooth-brushes."(40) He also condemned the collaboration(41) that was at the heart of the American Renaissance-an opinion seconded by a reporter in 1881: One leaves the rooms with the feeling that a great deal of talent and industry has been rather fruitlessly expended upon a work which any one of the artists employed would have made more effective.(42) The second floor of the armory was devoted largely to the rooms created by the individual companies, which vied with each other "to secure the most artistic designs and the best mechanical execution," as Clark noted.(43) Each company was allotted six thousand dollars from the proceeds of the 1879 fair, which they used to decorate their rooms, although some spent more than double that amount. Among the firms commissioned by the companies were Pottier and Stymus, Herter Brothers, A. Kimbel and J. Cabus, Roux and Company, and George C. Flint and Company. Some of the rooms were so lavish that the New York Times published an article in 1880 entitled "The Seventh's New Home: Company Rooms Resemble the Private Libraries of the Aesthetic Millionaire - Every Convenience for 1,000 men."(44) Each company room had a fireplace, and there were lockers for the members along the walls. The decoration was altered over the years to accommodate changing tastes with the exception of Company K's room (see Pls. VIII, IX). Its members were among the most affluent in the regiment and maintained the original decoration of 1880. Except for a missing frieze around the top of the walls, the architecture of the room is much as it always was. The decor was designed by the architect Sidney V. Stratton, a member of the company, who drew heavily on his New York House and School of Industry, the earliest building in the Queen Anne style in the city, which had also been completed in 1880 (Fig. 5).(45) Paul Haydon observed that the Company K Room looks as if it were the New York House and School of Industry turned inside out. The furnishings, which are no longer in the room, were provided by A. Kimbel and J. Cabus, a firm that worked extensively in the Renaissance and Gothic styles.(46) The armory is still much sought after for community events and is increasingly appreciated as an encyclopedia of New York's cultural and aesthetic climate during the late nineteenth century. With luck, this crumbling landmark will soon be restored to the glory of which the Seventh Regiment was so proud. For their assistance with this article I would like to thank David L. Dalva, Paul B. Haydon, Colonel George Kantor, and Jay Shockley. 1 The overtly fortified design of the Seventh Regiment Armory was copied until about 1910, when less defensive designs became popular. See Robert M. Fogelson, America's Armories: Architecture, Society, and Public Order (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1989), pp. 48-55, 189. 2 In 1947, when the federal government reorganized the National Guard, the Seventh Regiment ceased to exist as an active military unit. Many of the regiment's archives are in the New-York Historical Society in New York City. 3 Since 1942 the building has been managed by the New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs. Recently there has been significant water damage to the interior decorative finishes. The Seventh Regiment Armory Conservancy has proposed an ambitious plan for stabilization, restoration, and development. See the brochure "A Proposal for the Restoration and Revitalization of the Seventh Regiment Armory" (Seventh Regiment Armory Conservancy, New York City, 1998) and two articles on the condition of the armory in the New York Times, March 6 and 7, 1998. 4 New York Times, April 10, 1880. 5 Emmons Clark, History of the Seventh Regiment of New York, 1806-1889 (Seventh Regiment, New York, 1890), vol. 2, p. 290. 6 "The New York Seventh," Harper's Weekly, vol. 24 (May 8, 1880), p. 295. 7 Clark, History of the Seventh Regiment, vol. 2, p. 135. 8 Resolution adopted by the Board of Officers on January. 15, 1876 (see ibid., p. 238). 9 Fogelson, America's Armories, pp. 54-55. 10 Edward Strahan [Earl Shinn], "The Seventh Regiment Fair," Art Amateur, vol. 2, no. 1 (December 1879), p. 2. 11 See the New York Times, November 14, 16, 18, and 25, 1879. 12 November 28, 1879. 13 Clark, History of the Seventh Regiment, vol. 2, p. 301. The value of the sum today was acquired from the "Inflation Calculator"on the Internet at www.westegg.com/inflation/. 14 "The New York Seventh," p. 295. 15 Both buildings of Grand Central Depot were, in turn, inspired by Saint Pancras Station (built 1863-1868) in London and the adjoining Midland Grand Hotel (built 1866-1876). See Roger Dixon and Stefan Muthesius, Victorian Architecture (Oxford University Press, New York, 1978), pp. 81, 83. 16 "A Proposal for the Restoration and Revitalization of the Seventh Regiment Armory," p. 2. 17 Clark, History of the Seventh Regiment, vol. 2, pp. 298-299. 18 Letter from Cropsey, Warwick, New York, to Maria Cropsey, New York City, October 18, 1879 (Newington-Cropsey Foundation, Hastings-on-Hudson, New York, file four JFC-Maria 1870s). Sulesky (also Sullejewski and Sulisky) was listed as a painter in New York City directories between 1873 and 1887. I would like to thank Christian Bjone, Tom Nimen, and Michael Kozmiuk for their help with the rendering in Plate V. 19 "Specifications of Painting, and Materials required in finishing, and decorating the Large Drill Room of the 7th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue" (Newington-Cropsey Foundation), also Archives of American Art, New York City, Cropsey Papers, NCF, microfilm roll 905. 20 Cropsey's 1880 drawing of the coat of arms, which is after one created by Asher Taylor (1800-1878) in 1835, is illustrated in ANTIQUES, November 1986, p. 1004, Fig. 8. 21 New York Times, April 10, 1880. 22 Quoted in the New York Landmarks Preservation Commission report, "Seventh Regiment Armory Interior..." (Landmarks Preservation Commission, New York City, 1994), section 2, p. 20. 23 Quoted ibid., section 1, p. 12. 24 Ibid., section 1, p. 3. 25 Paul B. Haydon, the curator of the Seventh Regiment Fund, recently discovered that Flint decorated the Company A Room (Regular Monthly Meeting Book, 18761894, Company A, September 27, 1880). The Meeting Book is housed in the armory. 26 Quoted in "Seventh Regiment Armory Interior," section 2, p. 17. Irving and Cassone of Boston bought A. H. Davenport in 1914. 27 Ibid., section 2, p. 9. 28 "The Seventh Regiment Armory: An Investigation and Analysis of a Herter Brothers Interior" (Masters thesis, Historic Preservation Program, Columbia University, New York City, 1991), pp. 55-56. 29 Profits from the art fair amounting to $20,000 were spent on decorating the Veterans' Room and $10,200 on the Library (see Sophia Duckworth Schachter, "The Seventh Regiment Armory of New York City: A History of Its Construction and Decoration" [Master's thesis, Historic Preservation Program, Columbia University, 1985], pp. 49, 56). I would like to thank Mrs. Schachter for kindly sharing her thesis with me. 30 William C. Brownell, "Decoration in the Seventh Regiment Armory," Scribner's Monthly, vol. 22, no. 3 (July 1881), p. 371. Although Brownell states that Saint-Gaudens and Armstrong worked on the room, there is no documentary corroboration. 31 "Louis Comfort Tiffany at the Metropolitan Museum," Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, vol. 56, no. 1 (Summer 1998), p. 4. 32 "The Seventh Regiment Armory," Decorator and Furnisher, vol. 6, no. 2 (May 1885), p. 43. 33 Mary Warner Blanchard, Oscar Wilde's America: Counter-culture in the Gilded Age (Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, 1998), pp. 96-97. 34 "A New Renaissance: Stained Glass in the Aesthetic Period," in Doreen Bolger Burke et al., In Pursuit of Beauty: Americans and the Aesthetic Movement (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1986), p. 189. 35 Blanchard, Oscar Wilde's America, p. 26. 36 Mrs. Burton Harrison, "Some Work of the 'Associated Artists,'" Harper's Monthly, vol. 69, no. 411 (August 1884), p. 350. 37 The Veteran's Room Seventh Regiment N G S N Y Armory (n.p., 1881), p. 9. 38 New York Times, April 23, 1881. 39 Marilynn Johnson, "The Artful Interior," in Burke et al., In Pursuit of Beauty, p. 126. 40 "Decoration in the Seventh Regiment Armory," p. 375. 41 Ibid., p. 380. 42 "The Seventh Regiment Veterans' Room," American Architect and Building News, vol. 9 (June 18, 1881), p. 299. 43 History of the Seventh Regiment, vol. 2, p. 285. 44 April 10, 1880. 45 See the report "The New York House and School of Industry, 120 West 16th..." (New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, 1990). 46 Marilynn Johnson, "Art Furniture: Wedding the Beautiful to the Useful," in Burke et al., In Pursuit of Beauty, pp. 155-156. MARY ANNE HUNTING writes frequently about architecture and the decorative arts. COPYRIGHT 1999 Brant Publications, Inc. COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group |

|

|

notes |

GOVERNOR: FIRST STEP TO RESTORE SEVENTH REGIMENT ARMORY

|

|

links |

http://www.knickerbockergreys.org/index.html |