|

New York

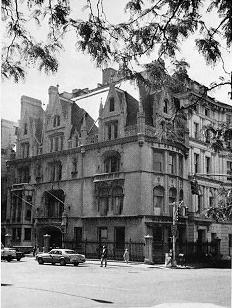

Architecture Images-Upper East Side

Ukranian Institute |

|

architect |

C.P.H. Gilbert |

|

location |

2 East 79th St. |

|

date |

1899 |

|

style |

French Renaissance |

|

construction |

limestone |

|

type |

House |

|

|

|

|

|

images |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not many people know that the grand French Renaisance-style chateau on the southeast corner of Fifth Avenue and 79th Street is actually open to the public. Built for a businessman and art collector named Isaac D. Fletcher in 1899, and later home to oil millionaire and scandal-ridden Harry F. Sinclair as well as Augustus Van Horn Stuyvesant (descendant of Peter Stuyvesant, the colonial director famous for his $24 deal with Manhattan's Native Americans), this mansion was purchased by the Ukranian Institute in 1955. The Institute hosts a multitude of events each year including art exhibitions, auctions, literary evenings, theatrical performances, lectures, concerts, forums and symposiums, and other social gatherings, both for members of Ukrainian associations and the public at large. Each of these events provides an opportunity to glimpse the splendors of a grand turn-of-the-century town house. Note the magnificent carved woodwork on the broad staircase and the many touches of elegance throughout the three floors that are generally open for view. |

|

|

Nestled in the midst of "Museum Mile", which includes the Guggenheim Museum and the Frick Collection, and diagonally across from the Metropolitan Museum on the southeast corner of 79th Street and 5th Avenue, is one of the most magnificent and regal turn-of-the-century mansions in New York City today. This French Renaissance style structure houses the jewel of the Ukrainian community: the Ukrainian Institute of America. The history of the acquisition of the mansion by Mr. William Dzus, the founder of the Ukrainian Institute of America, dates back to 1898 when Isaac Fletcher, a banker and railroad investor, commissioned the famous architect C.P.H. Gilbert to build a house using William K. Vanderbilt's neo-Loire Valley chateau as its model, on the property which was originally the Lenox farm. Mr. Fletcher was so pleased with his new home that he hired Jean Francois Raffaelli to paint a portrait of it; the painting, the mansion and the Fletcher's extensive art collection were all eventually bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1917. Harry F. Sinclair, the founder of the Sinclair Oil Company, purchased the Fletcher Mansion in 1920 and sold it in 1930 to Augustus Van Horne Stuyvesant, Jr., a descendant of Peter Stuyvesant. A bachelor and recluse, Augustus Stuyvesant occupied the mansion with his unmarried sister until her death in 1938, then lived out the remaining years of his life until 1953 with just his butler and footman to serve him. William Dzus, inventor and owner of the Dzus Fastener Company in West Islip, Long Island, New York founded the Ukrainian Institute of America, Inc. in 1948, for the purpose of promoting Ukrainian art, culture, music, and literature. At that time, the Ukrainian Institute was located in the Parkwood mansion in West Islip, Long Island. The increasing membership and growth of the Institute prompted Mr. Dzus to search for a larger facility; he authorized the treasurer of the Dzus Fastener Company, Francis Clarke, to look for new, larger quarters in New York City. The capacious Fletcher Mansion with its prestigious address and unique architectural style, was perfectly suited for the Ukrainian Institute and in 1955, the mansion was purchased by the Ukrainian Insitute of America corporation with with the charitable generosity and support of Mr. Dzus. In June of 1962 the mortgage was paid off and subsequently the Ukrainian Institute of America attained landmark status. The Ukrainian Institute takes great pride in the fact that almost 50 years after moving into its new home at 2 East 79th Street, William Dzus' dreams and aspirations are still very much alive and thriving. Boasting a membership of over 400 people, some of the events sponsored by the Institute in the last year were: the Les Kurbas Theater performing a memorable apocrypha based on the writings of Lesia Ukrainka; a scholarly conference on the occasion of the 130th anniversary of Mr. Hrushevsky's birth; a seminar with Adrian Karatnycky, President of the Freedom House, on "Ukraine, the United States and Russia"; commemoration of the 10th anniversary of the Chornobyl nuclear disaster with an exhibit of photos, paintings and videos; and a business conference in conjunction with the Consulate General of Ukraine in New York. The Music at the Institute classical music concert series under the capable directorship of Mr. Mykola Suk and leadership of Dr. Taras Shegedyn, continues to draw large audiences. |

|

|

Commentary by various authors Andrew S.Dolkart, "Touring The Upper East Side, Walks in Five Historic Districts" (The New York Landmarks Conservancy, 1995): "Here, the rural chateau form is compacted by the demands of an urban site, yet the house has a lively asymmetrical shape, and is complete with a moat-like areaway with front stairs suggestive of a draw bridge. The carved detail is outstanding: the winged monster ensconced on the chimney, the paired dolphins on the stone entrance railings, the rustic couples who flank the entrance, and the heads dripping from the second-floor window are but a few of the whimsical ornamental touches." Elliot Willensky and Norval White, "The A.I.A. Guide to New York City, Fourth Edition" (Three Rivers Press, 2000), describe this as a "French Gothic palace," adding that "the classic comparison is the house of Jacques Coeur (ca. 1450) at Bourges." |

|

|

Streetscapes/Charles Pierrepont Henry Gilbert;

A Designer of Lacy Mansions for the City's Eminent By CHRISTOPHER GRAY Published: February 9, 2003, Sunday THE lacy limestone pinnacles of the 1899 Fletcher mansion at 79th Street and Fifth Avenue are gleaming, the streaks of soot and dirt removed by a cleaning late last year by its owner, the Ukrainian Institute of America. This neo-French Gothic house is one of the touchstone works of the architect Charles P. H. Gilbert, who not only designed mansions for the leading families of New York but could also shoot at a gallop from underneath a horse. Charles Pierrepont Henry Gilbert -- usually referred to in architectural sources as C. P. H. Gilbert -- was born in 1861 to a family that traced its lineage to 17th century England. His 1952 obituary in The New York Times said that early in his career he had ''practiced architecture in the mining towns of Colorado and Arizona.'' But by the late 1880's he was designing upper class houses in Brooklyn, both for developers and individual owners. For the developer Harvey Murdock, Gilbert designed several picturesque houses with Romanesque, Dutch, shingle and terra cotta accents on Montgomery Place, between Eighth Avenue and Prospect Park West -- Nos. 11, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 25, 36-50, and 54-60 form a stunning display of his versatility. Those who subscribe to the modern bent of contextual architecture might be indignant at Gilbert's wildly varying houses of about 1889 at 313 and 315 Garfield Place in Park Slope -- No. 313 tall and thin, with a medieval palette of dark stone, and No. 315 short and wide, with light-colored brick and a much more delicate design, the two forming a sort of architectural Mutt and Jeff. Neither ''respected'' its neighbor, in the sense that modern preservationists use the word. Another element crept into Gilbert's work about this time -- the lacy forms, decorated gables and lighter stone, often limestone, of late French Gothic. One of the first was a mansion for the shoe dealer John Hanan at Carroll Street and Eighth Avenue in Park Slope, around 1890. The Hanan house, demolished in the 1930's, still had the heavy, rock-faced stone common to the Romanesque revival of the 1880's, but period photographs indicate that the masonry was of a much lighter cast than the usual brownstone and, more significantly, was detailed with delicate French Gothic detail in limestone at the doorway and roof line. By the mid-1890's Gilbert was designing buildings in Manhattan, among them the suite of town houses at 72nd Street and Riverside Drive, including 311 West 72nd, 1 Riverside Drive and 3 Riverside Drive. The first two were more conventional limestone town houses -- elegant but hardly memorable -- but the Philip Kleeberg house at 3 Riverside Drive, designed in 1896, is a lacy froth of French Gothic curlicues, moldings and other details. In 1897 Gilbert attained his signature style of architecture, the no-holds-barred French Gothic design of the Isaac Fletcher house at 79th and Fifth, completed in 1899. The Gothic moldings, high mansard, giant entryway and forest of pinnacles make the building as much a fantasy as a work of architecture. Around the corner, the contemporaneous Converse house, designed by Gilbert at 3 East 78th Street, offers a nice little side-street riff on the same style. A third contemporaneous Gilbert mansion was that of Frank W. Woolworth at the northeast corner of 80th Street and Fifth Avenue, now demolished but similar to the Fletcher and Kleeberg houses. The Woolworth connection has led some to confuse C. P. H. Gilbert with Cass Gilbert, the architect Woolworth chose for his skyscraper at Broadway and Barclay Street, built in 1913. There was also another prominent architectural Gilbert at the time, Bradford Lee Gilbert, who designed many railroad stations; none are closely related. Around this time C. P. H. Gilbert served in the Spanish-American War. He was a founder of the exclusive cavalry unit Squadron A, and a member of the Racquet & Tennis and other clubs. IN 1902 Gilbert designed another imposing house, that of Joseph R. DeLamar at the northeast corner of 37th Street and Madison Avenue. Now the Polish Consulate, that structure lacks the lacy decoration of the high French Gothic structures, but its bloated size gives it the opulent quality of the earlier buildings. By 1900 he was firmly entrenched as a specialist in mansion design, with commissions for the Baches, Reids, Wertheims, Sloanes and other families of comparable wealth. In all, he designed more than 100 large houses and mansions in Brooklyn and Manhattan. A slightly later work is Gilbert's house for Felix Warburg, at the northeast corner of 92nd Street and Fifth Avenue, completed in 1908. Now the Jewish Museum, and somewhat diluted by the addition to the north that replicated the style of the original, this mansion is in the vein of the Fletcher house, although it edges toward a simpler expression, with somewhat less detail. In collaboration with J. Armstrong Stenhouse, Gilbert designed a very reserved palazzo for the banker Otto Kahn. The building, now the Convent of the Sacred Heart, was designed in 1914 and completed in 1918 at 91st Street and Fifth Avenue. Gilbert even ventured into apartment design with his 1917 French Gothic building at 1067 Fifth Avenue, near 87th Street, which repeated much of the lacy detail of his houses of two decades earlier. Although it is a multiple dwelling, the building had near-mansion-size apartments, including a duplex with nine servants' rooms. After several more city and country mansions in the 1920's, Gilbert appears to have retired from architecture -- and as modernism advanced, his buildings for a time seemed more and more irrelevant. In the 1939 ''W.P.A. Guide to New York City,'' he is not even listed in the index -- although Cass Gilbert is mentioned 11 times. But in 1967, in the midst of a renewed interest in preservation and the city's architectural history, the ''A.I.A. Guide to New York City,'' by Norval White and Elliot Willensky, indexed 11 C. P. H. Gilbert buildings (and only 10 by Cass Gilbert). The 2000 edition lists 24 by C. P. H. and 8 by Cass. Cass Gilbert is the subject of at least eight books, but C. P. H. Gilbert is comparatively little known, especially regarding his personal life. It is clear he did well -- the 1915 census lists him at age 52 at his town house at 33 Riverside Drive (since demolished) along with his wife, Florence, and their son, Dudley, and seven servants, including a butler and a maid. Three years earlier the household must have been alarmed when Dudley, then 13, disappeared on the way to a dentist's appointment and later sold his overcoat to buy a steamship ticket from Philadelphia to Europe -- although he was turned back by the captain. Dudley's son, Dudley A. Gilbert, who lives in East Lyme, Conn., recalls that his grandfather had a sense of humor and was ''firm in purpose, which boils down to stubborn.'' Edith Welch, Dudley A. Gilbert's sister, who lives in New Hampshire, says that family stories back up the account of her grandfather's experience in Colorado and Arizona designing opera houses and banks. ''My own father loved to tell the story that out west his father learned how to do trick riding, where you go under the saddle and shoot,'' she recalled. ''He did that at the Squadron A Armory on 94th Street and Madison. My grandfather also loved to skate, and gave me my first pair of ice skates.'' Although her grandfather was part of high society in New York and Newport, R.I., ''he was not pretentious,'' she said. But she said that he was considered a taskmaster by his architectural employees. To them, his middle initials, ''P. H.,'' she said, ''stood for 'Particular as Hell.' '' Published: 02 - 09 - 2003 , Late Edition - Final , Section 11 , Column 1 , Page 7 Copyright New York Times. |

|

|

links |

http://www.ukrainianinstitute.org/index.html |