|

New York

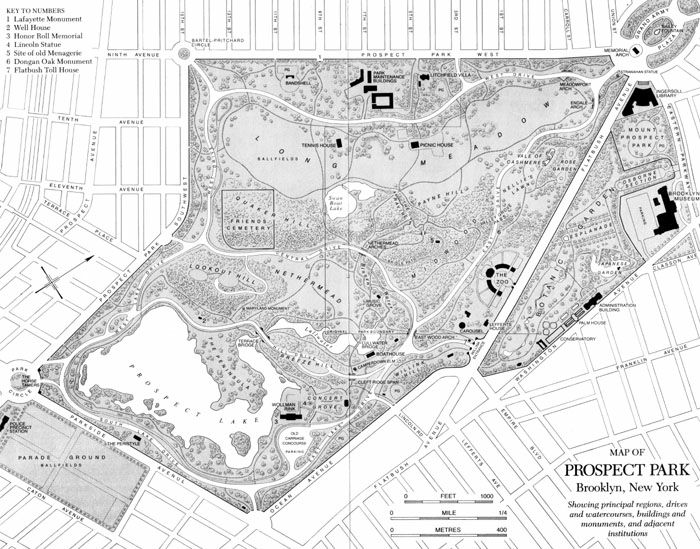

Architecture Images-Brooklyn Prospect Park |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

architect |

Olmsted and Vaux | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

location |

Prospect Park, Grand Army Plaza, Prospect Park W, Prospect Park SW., Parkside Ave., Ocean Ave., and Flatbush Ave. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

date |

Designed 1865. Constructed 1866-1873. Frederick Law Olmsted & Calvert Vaux. Various alterations. Scenic landmark. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Across the East River from New York City

sprawled another great metropolis, Brooklyn. In the late 1850's,

Manhattan was linked to Long Island only by ferries, and the independent

City of Brooklyn had the third largest population in the United States.

A movement was afoot in Brooklyn to make a sizable public park, similar

to that in its sister city, and also a number of satellite parks. At the

solicitation of the citizens, the Legislature of the State of New York

passed an act on 18 April 1859: "To Authorize, the Selection and

Location of Certain Grounds for Public Parks, and also for a Parade

Ground for the City of Brooklyn." Fifteen commissioners were appointed

to choose suitable sites, and on 3 February 1860 they submitted their

recommendations. These included four major reserves: one was in Brooklyn

proper, the second at Ridgewood, the third at Bay Ridge, and the fourth

at New Lots. Three small local parks also were mentioned, one being a

block on Brooklyn Heights bounded by Remsen, Furman and Montague

streets, and Montague Terrace, to be set aside because of its

superlative view of the harbor.

The largest and by far the most important of the seven proposals was referred to as Mount Prospect Park. Its name came from the bill on which the reservoir was located, near the intersection of Flatbush Avenue and present Eastern Parkway. The commissioners stressed that it was expedient for the purity of the water to retain undeveloped ground around the reservoir; and, as with the recommendation for the small park on Brooklyn Heights, they made a case for the vista from Prospect Hill, which overlooked the eastern part of Kings County, Brooklyn, Jamaica Bay, New York, the harbor, the New Jersey shore, and the Narrows and adjoining slope of Staten Island. The park was to consist of 320 acres, bounded by Washington Avenue from Warren to Montgomery streets, then following the Flatbush township line south-southwesterly to a point now in Prospect Park about equidistant from the three sites of the Nethermead Arches, and Lullwater and Terrace bridges, then west-northwest along 9th Street to Tenth Avenue (approximately the site of the Tennis House), then along Tenth Avenue to 3rd Street (northeast corner of the Litchfield Villa lot), then over to Ninth Avenue (Prospect Park West), then north-northeast to Flatbush Avenue, a short distance along this thoroughfare (crossing what is currently Grand Army Plaza) to Vanderbilt Avenue, four blocks north to Warren Street, and back to the beginning at its intersection with Washington Avenue. The area designated took in most of the present grounds of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, all of the Museum, Library and old reservoir, and almost as much land lying due north, plus about two-fifths of the final Prospect Park precinct. The committee justified the economics of the park venture with the argument that the increased value of real estate in the vicinity would bring in greater tax returns to counterbalance the expenditure. They buttressed it with the humanitarian appeal that: "The intense activity and the destructive excitement of business life as here conducted, imperatively demands these public places for exercise and recreation"; and they noted that, although not centrally located in Brooklyn, Mount Prospect Park would be easily accessible "to the masses of our people," either "on foot or the cheap railroad lines."

Located within both the first and final proposals for the park area is the site of the easternmost encounter of the Battle of Long Island of the American Revolution, on the east side near the old Brooklyn-Flatbush line. Here stood the great white oak, that had been cited by Governor Dongan as a marker on the boundary between the two townships, felled as a barrier across the narrow lane to impede the British. Many other trees had been cut to make rude fortifications along the summit of the wooded ridge above Valley Grove Pass, as colonial forces under General Sullivan lay in wait for the enemy's advance on the fateful morning of 27 August 1776. They were greatly outnumbered; and, after their first volley had been fired and there was not time for reloading, a rifle butt served as poor defense against pitiless Hessian bayonets in hand-to-hand fighting, with the result that the encounter turned into a massacre and rout on the part of the Americans. Later in the day, General Stirling sought the Hessians in Prospect Woods and yielded himself, rather than surrender to an English officer. The Maryland Monument, at the foot of Lookout Hill west of Terrace Bridge, and several bronze plaques north of the modern zoo commemorate the events. Having been an historic setting played an important, persuasive role throughout the lengthy process of the park becoming a reality.

The State Legislature confirmed the recommendation by an act passed 17 April 1860, and through this document the right to acquire the designated land became law. Also, the officials of Brooklyn were empowered to issue bonds to cover the costs of the endeavor. A turnover in the roster of the Board of Commissioners occured during the year, with only one name surviving from those of the original fifteen selectees (that of Thomas G. Talmage), and the current seven members elected James S. T. Stranahan (1808-98) president, and R. H. Thompson secretary. In the person of the new President of the Board, Prospect Park gained its most ardent champion. Stranahan, who was a millionaire, served in this post without remuneration for 22 years and, upon leaving, he presented the City a check for $10,604.42 to cover a shortage claimed against the commission during his period of tenure. The first expenditure of the commissioners was to hire a topographical engineer, which specialist was Egbert L. Viele, the original Chief Engineer for Central Park. Viele examined the premises and composed a written report, in which he indicated his conviction that "the primary object of the park [is] as a rural resort, where the people of all classes, escaping from the glare, and glitter, and turmoil of the city, might find relief for the mind, and physical recreation." The city grinds down its dwellers, he says: "while on the other hand nature in its beauty and variety never palls upon the senses! never fails to elicit our admiration; whether displaying its wild grandeur in the vast solitudes of the forest, . . . whether bursting the fast of winter, it opens its buds in spring-time, or yielding to the chilling blasts it scatters its autumn leaves -- it conveys in all its phases and through all its changes no emotions which are not in harmony with the highest refinement of the soul." The tone of this prose poem, by a nineteenth century American, is not unlike that of the eleventh century Chinese, quoted at the beginning. Kuo Hsi recommended, as a substitute for direct communion with nature, a "landscape painted by a skilled hand." Viele exhorts the natural garden, which to "the weary toiler . . . supplies a void in his existence and sets in operation the purest and most ennobling of external influences." It was a great and wonderful philosophy of compensation transposed into modern terms and means. Viele calls his design of 1861 Plan for the Improvement of Prospect Park, eliminating once and for all the "Mount" in the title. He locates the main entrance at the junction of Flatbush and Vanderbilt avenues. Other entrances in the east section are at the corner of Warren Street and Washington Avenue, and midway along Washington Avenue. Entrances to the west section are at each of the lower corners, and another where 3rd Street and Ninth Avenue meet. The driveways wind through the grounds without definite direction, ascending to a climax on the Esplanade atop Mount Prospect, where carriages might pause 200 feet above sea level to allow their passengers to enjoy the spectacle. A flower garden, with meandering paths, adjoins the water-supply basin. The roads cross over Flatbush Avenue on viaducts at two places, one near the main entrance and the other by the reservoir, and under it by means of a tunnel at the south end. In the lowest corner, on 9th Street, is a botanical garden with intersecting radial and concentric curved walks. A small horseshoe shaped lake is indicated to the west, about where Swan Boat Lake later materialized. The chief meadow is between 3rd Street and Flatbush Avenue, anticipating the northern end of Long Meadow. Viele labeled this feature "The Parade," ignoring the previously published statement of the commissioners that they deemed it unsuitable to have a drill field inside a park of this species. The report concludes with technical data on drainage, manuring, trenching, planting, and building cracked-rock roads, as these were applicable to the situation. The work of conversion was estimated to cost $300,000, the largest item, $75,000, allocated for roads. The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 paralyzed the Prospect Park project, just as it did many other contemporary endeavors in America. At least in this instance the delay proved to be a blessing in disguise, allowing time for reflection and determination. In the brief report of the commissioners made in January 1862, Stranahan declared that "Prospect Park in the city of Brooklyn must always be conceded as the great natural park of the country." The one constructive task that moved forward during the interim was making estimates of private properties designated within the scheme; and, because of the easing of the real estate market due to the lack of security accompanying the conflict, it was recognized as "a peculiarly favorable period for making payment to the landlords." The report three years later stated that compensation would amount to $1,357,606, and that remittances already were in progress. Decent houses thus acquired were to be rented until the ground they stood on was ready to be improved for the park, whereas shanties and their squatter tenants were "being quietly removed." A very important item in this report was the appendix, involving a reconsideration of the boundaries by an expert engaged for the purpose. The survey had been put into the capable hands of Calvert Vaux (1824-95), the British architect who joined forces with Andrew Jackson Downing in 1850 and worked on the landscaping of the Smithsonian Institution and part of the Capitol grounds in Washington prior to Downing's drowning in the sinking of the steamboat Henry Clay two years afterward. To his late friend and associate Vaux dedicated a collection of his own architectural designs brought together in a book entitled Villas and Cottages, published in 1857. As we have seen, the following year Vaux collaborated with Olmsted on the plan that won the competition for Central Park and was appointed Consulting Architect. The next eight years of experience in the Manhattan park well qualified him for giving sound advice on Prospect. Calvert Vaux did not approve of the tract being divided by Flatbush Avenue. The overpasses were awkward and an expense that could be applied to better advantage purchasing additional contiguous land. He favored concentrating on and extending the western section, because the reservoir, in the other division, could not be landscaped attractively. Yet he felt it would make a worthwhile supplement to the park, because of its elevated promenade. The primary deficiency in the existing grounds was a place suitable for a large lake, which would be a valuable asset, especially because ice skating on it would prolong the usefulness of the park into the winter. He complained that the land dug in Central Park was too small and estimated that the lowland north of Franklin (Parkside) Avenue in Brooklyn could accommodate an articial body of water 50 or 60 acres. This would require a vast annex to the south, in Flatbush; but "the amount relized for the sale of the north-easterly section would go far to defray the cost of the proposed addition, if it would not pay for it entirely." Another feature established at this time was that the principal entrance ot the park would "unquestionably be near the point where Flatbush . . . is intersected by . . . Ninth avenue." An accompanying sketch plan, dated 4 February 1865, indicates an elliptical plaza at the north end, the shape, size and location of which accord with what exists there today. The preliminary report on boundaries led, later in 1865, to the reengagement of Vaux, together with his partner Olmsted, to create a whole new plan. Of the two men, Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) was the better informed on growing plants and landscaping in general. Olmsted was a native American, born in Hartford, Connecticut, and he had learned the rudiments of rural skills as a little boy visiting relatives in the country. Later, at home, he frequented the Harford Public Library, perusing such books as Sir Uvedales Prince's An Essay on the Picturesque and William Gilpin's Remarks on Forest Scenery, both published at London in the early 1790's. At fourteen Olmsted apprenticed to a topographical engineer and learned surveying; at twenty-one he became a seaman and shipped aboard the Ronaldson to Hong Kong; at twenty-five he finished a course at Yale and took up scientific farming, first at Gilford and then on Staten Island, where he spent much of his time in landscaping and yet was successful as a farmer. He was thirty-five when he assumed the role of Superintendent in Central Park, and the next year he devised the Greensward plan with Vaux, who was two years his junior. Olmsted had been in California in 1865, when the survey was requested, and that Calvert Vaux had made it alone indicates that both men were proficient at landscape gardening, but, generally, Olmsted is considered the genius in composing scenery and Vaux in planning architectural accents. The plan for Prospect Park conceived by Olmsted and Vaux in 1866 was accompanied by a lengthy essay, which the Board summarized for the Brooklyn Common Council as follows: The ground features of the plan are simple and easily comprehended; but the Commissioners wish to direct attention particularly to three regions of distinct character embodied in it, in each of which, it will be observed, the suggestions of the natural condition of the land are proposed to be developed. They are, first, a region of open meadow, with large trees singly and in groups; second, a hilly district, with groves and shrubbery; and third, a lake district, containing a fine sheet of water, with picturesque shores and islands. These being the landscape characteristics, the first gives room for extensive play grounds, the second offers shaded rambles and broad views, and the third presents good opportunities for skating and rowing. With this thumbnail description in mind, let us look at the plan itself. First of all, the landmark that had given title to the park, Prospect Hill, was outside the confines. In outline and paramount features, the design is the archetype of the garden that was eventually objectified. The irregular shape is six-sided, coming to a point at the north extremity on an oval plaza. The northeast side is bounded by a stretch of Flatbush Avenue; the east limit steps in and continues almost directly south along what is now Ocean Avenue. The southeast base is Franklin (Parkside) Avenue, ending at present Park Circle, foyer to the southernmost entrance. The southwest side is framed by Coney Island Road (Prospect Park Southwest), which curves into 15th Street. This meets Ninth Avenue (Prospect Park West) at right angles, the intersection embellished by another circle (Bartel-Pritchard). Ninth Avenue or Prospect Park West returns us to the place of beginning. Of the seven drive entrances, all but one are at or near one of the corners of the configuration, the exception being on the upper west side at 3rd Street. It is of interest that only one other has been added, that on Ocean Avenue, and it is without elaboration. An element not to be realized is the overpass crossing Flatbush Avenue to the reservoir lot. The report proposes a Parade Ground across Franklin (Parkside) Avenue, although it is not indicated on the map. The park proper contains 526 1/4 acres. Its compact, arrowhead shape is more appropriate to a natural-landscape garden than the elongated regular rectangle of Central Park, in which one is always conscious of the surrounding city. The final limits of the Brooklyn precinct had been chosen by the landscape architects themselves, and the area was not encumbered by reservoirs, neither did it require division by transverse roads. The boundaries enclosed less land but the space could be put to more effective use, as in the case of the tremendous sweep of meadow nowhere possible in the New York park. It was attained with less labor because the western end of Long Island had escaped the glacial upheavals and was free of the harsh protrusions of jagged rock found on Manhattan. A brilliant innovation in the Brooklyn park is the ridge of heavily planted earth just inside the walls, that makes an effective screen blocking out the urban scene and permitting an instant illusion of being in the country. A glance at the 1866 Olmsted-Vaux plan for Prospect Park and comparison with the contemporary scheme for Central show what a tremendous simplification and unification has been achieved in the Brooklyn design. The three elements mentioned in the commissioner's summary roughly dispose themselves into approximately equal thirds of the park. The open meadow occupies a long strip adjacent to the northwest boundary on Ninth Avenue. Thrice labeled here "The Green," after 1870 it became known as Long Meadow. Beginning inside the principal entrance on the Plaza, the crescent-shaped lawn, covering 75 acres curves toward the center of the park and out again to the entrance at 15th Street and Ninth Avenue (Bartel-Pritchard Circle). The West Drive winds through the trees framing the concave side of the crescent. Wooded hills, constituting the second element, occupy the region running through Prospect Park east of Long Meadow. It is a very irregular and varied section, taking on almost the character of a mountain defile in the stretch north of the Nethermead, between the Green and East Drive, and that of a stony valley with a brook in the Ravine extending from the Lily Pond above the Lullwater to Swan Boat Lake. The source of water is an artificial spring immediately to the south, at the base of Quaker Hill. The ground rises steadily to the summit of adjoining Lookout Hill, the highest prominence in the park, at the head of the peninsula jutting out into the Lake. Woods, or at least arrangements of trees, border other features of the park and weave them all together into a coherent whole. The third element is the Lake or, more generally, water, of which the 60-acre lake is the most conspicuous member; included are the narrow lagoons leading to the Lullwater, the stream in the Ravine with its assorted pools, and the spring that feeds the entire system. The Lake overspreads most of the south triangle of the reserve and its tributary reaches far inland. We have here the constituents of the Chinese landscape, as may be seen in any painting of scenery done in the Far East. The Chinese term for "landscape" is composed of two words, shan and shui. The first means "hill" and the second "water." The characters for these words appear at the beginning of this essay, as the heading for the translation for the Kuo Hsi quotation, the third character in the title being hsun, "treatise." The drives meander inside the perimeter of Prospect Park, encompass the Lake, Lullwater and Lily Pond, and traverse the woods from Willink Entrance on Flatbush Avenue over Breeze Hill and around the Nethermead, between Lookout Hill and Quaker Hill, to the 16th Street Entrance on Coney Island Road (Prospect Park Southwest). Walks and bridle paths (referred to in early accounts as "rides") tend to follow the contours of the drives, but these also branch out considerably more, enmeshing many parts not accessible to the drives. The carriage roads were of crushed rock and had an average width of 40 feet, increasing to 60 at the principal entrance. A narrow roadway ascends Lookout Hill to the paved plateau on top, described as "an oval court for carriages, three hundred feet long and one hundred and fifty wide." A terraced platform adjacent was to be provided with seats and awnings, and a small building "for the special accommodation of women and children, and at which they might obtain some simple refreshment." An elaborate Eclectic stone tower was to have been built here too, affording an even better vista of the bays and surrounding lands to the west, and a bird's-eye view of demonstrations on the Parade Ground to the south. A second, and larger, concourse for carriages was to the east of the Lake, and next to it was a space labeled "Concourse for Pedestrians," a promenade that developed in 1870 and will be discussed below. Due west, on what came to be called Breeze Hill, was a lesser stopping place for carriages, permitting a panorama over the inlet of the Lake. Midway between here and the Lookout, at the head of the inlet north of the Peninsula, was to have been built the Refectory, with broad arched terraces overlooking the water. The name of Terrace Bridge close by recalls the project which, like the proposed structures on Lookout Hill, expired before realization. The Refectory was to have been the "principal architectural feature in the park," like a well-appointed inn in the country. Even though other minor aspects changed on maps issued within the next few years, the Refectory and Lookout persisted as long as Olmsted and Vaux had anything to do with the park. Afterward, when nothing came of the restaurant, Well House Drive was laid out from Terrace Bridge around the corner of the shore to West Lake Drive.

The upper reaches of the park were to present "a display of the finest American forest trees." Among native deciduous varieties in Prospect Park are to be found: American elm, the oaks and maples, yellow poplar or tulip tree, ash, red mulberry, wild cherry, dogwood, Kentucky coffee tree, sassafras and Osage orange. American conifers include the white pine, blue spruce, hemlock, and the bald cypress from southern swamps. On "the interior slopes of the Lookout and Friends' Hill" there was to be "a collection, arranged in the natural way, of the most delicate shrubs and trees, especially evergreens, both coniferous and of the class denominated in England American plants, such as Rhododendrons, Kalmias, Azaleas and Andromedas." The shore of the Lake was to be planted in "picturesque groups of evergreen and deciduous trees." From the beginning, many plants were introduced into the park from other parts of the world, some of them constituting gifts. Among the trees from Europe were: the sycamore maple (the leaf of which was taken over as the emblem of the Department of Parks), Norway maple, European lindens, English oak, English elm, Scotch elm, English hedge maple, European beech, European hornbeam, horse chestnut, and Austrian pine. The single most noteworthy example is the Camperdown elm near Cleft Ridge Span, a Scotch elm grafted on a normal elm and prized for its contorted horizontal branches. Set out in 1872, it was already considered a landmark when Louis Harman Peet published Trees and Shrubs of Prospect Park in 1902. Asian trees include the scholar or pagoda tree, ginkgo, tree of heaven, Chinese elm, Chinese tree lilac and magnolia. Among oriental evergreens are the Himalayan pine, Japanese Tanyosho pine or umbrella pine, and oriental spruce. A tree-moving machine was devised in 1867, enabling a good-sized specimen to be taken up, together with a large portion of soil around its roots, braced, and wheeled upright to be put into the earth at a different location. Numerous trees standing in Long Meadow were removed and placed elsewhere by this device. In 1872 there were 284 trees thus transplanted. The park maintained its own nursery, in which an average of 30,000 trees and 25,000 other plants were kept on hand, and during the first two years of building Prospect Park, over 73,000 trees and shrubs were set out from this stock. After considering trees, a word regarding the survival of wild life in this area should be in order. Of greatest importance are the birds. These little winged creatures need two simple requirements, cover and sustenance. Trees and other plants just discussed fill these needs and therefore attract the birds. Migrants are semi-annual visitors to Prospect Park, first lighting on Lookout Hill and following the ridge northward and then eastward, crossing Quaker Hill to the Pools and threading their way throught the Ravine, and leaving the park either at the Vale or Lily Pond. At one time there were numerous birds on the Peninsula, but the removal of the shrubbery and clamour from the skating rink opposite, in season, have ended their sojourn here. At the eastern end of the Ravine is an established community -- bullfrogs, who sometimes supply impromptu entr'actes during the Goldman concerts in the Music Grove on warm summer evenings. The other notable subhuman societies are the squirrels in the trees and the fishes and crustaceans in Prospect Lake. The presentation of the Report of Olmsted, Vaux and Company in January 1866 was the official birth certificate of Prospect Park. The plan was printed and distributed among the citizens of Brooklyn and, although there were a few die-hards who clung to the retention of the eastern sector, on the whole they responded with "a hearty approval of the design," and "no material objection was made to any of its prominent features." Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux officially were made Landscape Architects of Prospect Park on May 29th and given complete responsibility for everything that was to transpire in the venture. They were asked to prepare details of their plan and to organize a working force. The Board appointed Joseph P. Davis engineer in charge, and John Bogart and John Y. Culyer his principal assistants. The surname of the last caused some confusion in the appearance of Vaux's given name in print, sometimes coming out as a hybrid between Calvert and Culyer. The typographical error most appropriate to a landscape architect was "Culvert." The Legislature of the State of New York passed an act on 30 April 1866 sanctioning the change in land designation. An interesting problem arose over the Quaker Cemetery, located between Eleventh and Twelfth avenues and 9th and 14th streets, completely enveloped by the recent acquisition. The matter was discussed at length and finally settled by the Friends' retaining the southern two-fifths of the lot, or that portion interlaying 11th and 14th streets, to which they were assured direct passage through the reserve from the 16th Street entrance at all times. The ten-acre cemetery is still being used for burials but, as Quakers do not approve of ostentatious memorials or markers except for the fence enclosing it, one is hardly conscious of there being a graveyard in the park.

The first task preparatory to building Prospect Park was draining the land wherever necessary. Then construction began at the upper terminus. The processes involved were tearing down unwanted structures and removing the debris from the site, putting in drain and sewer lines, grading, building roads, bridle paths and walks, taking up trees and putting them elsewhere, and setting out new plants. These activities gradually proceeded southward along the east side of the park. The manual labor started in June 1866 with a crew of 300 men. Although declining during the winter months, the number of employees increased to a peak in October 1867, when 1,825 were on the payroll. After this, there was a leveling off, with an average of about 1,100 in the warm months of 1868, close to 1,000 in 1869, 750 in 1870, back up to 1,100 in 1871, and than a gradual reduction to about half this number in the depression year of 1873. Visitors to the park were a nuisance to the work crews during the construction period. Especially after the upper reaches of Long Meadow and the Woods were done and the scene of activities was the southern half of the reserve, people came in droves and destroyed much of the early planting through tramping on it. An average of 100,000 persons visited the park monthly during the summer of 1868, and by 1871 the count had increased to 250,000. But it was understood that the park is for people; and, for their use and enjoyment, benches of wood slats on iron framework were provided as soon as possible. Over 200 were installed in 1868, half of them 7 feet in length and the others 5 or 4 feet long.

The most appropriate structures in Prospect Park, for tying in with the landscape, were the rustic shelters, those with posts and lattice railing of rough tree trunks, and shingled or thatched roofs. These were of various oblong and polygonal shapes. Four were spaced along the east shore of the Lake, of which only one survives, the rectangular, hipped-roof Landing Shelter near the Carriage Concourse. These were viewing stations for western sunsets over the water. A five-sided rustic shelter stood on the spur at the south end of the Lake, nearest Park Circle, and an octagonal example stood on a high point in the Ravine, overlooking the bridle path spanned by Boulder Arch. A rustic arbor 111 feet in length was on the east side of the Lake, and another shaded a portion of the walk north of the Children's Playground. The Playground, developed in 1867, was provided with a lawn for various games, including croquet, a pool for the sailing of toy boats, a maze, and a heptagonal summer house. The first carousel was erected here in 1874. It was moved to Picnic Woods (west side of Long Meadow, back of Litchfield Villa) in 1885, and the Rose Garden was laid out in 1895 on the site of the Playground. The adjoining Vale of Cashmere bad just been renovated a year or two earlier, with additions of pedestals bearing urns, some connected by balustrades, and a fountain sculpture in the pool, making for a strange combination of rustic and classic elements. One other early building belonging to the rustic group was the picturesque Thatched Shelter, that stood midway between the second location of the carousel and Meadowport Arch. It had an H-plan and a steeply pitched roof pierced by dormers. The shelter also was called the "Swiss Thatched Cottage" and the "Indian Shelter." It burned in 1937. Several rustic bridges were in the park. A large one of 35 feet was the Binnen Bridge over the waterfall near the old boathouse on the Lullwater. Smaller examples were at the west end of the Ravine, lending a remote atmosphere. There were also more than 50 rustic seats of sassafras and cedar, and 800 rustic bird houses.

The first permanent structures were the arches on the upper and east sides of Prospect Park. These were pedestrian underpasses, allowing visitors to cross under the roads thus avoiding the hazards of traffic. The tunnels were provided with seats to serve a second function as comfortable rain shelters. The first two built were East Wood Arch under East Drive above the Willink Entrance approach, and Endale Arch near the entrance on the Plaza. The masonry of both is composed of alternating blocks of yellow Berea sandstone from Ohio and reddish brownstone from New Jersey, and the interior vaults are of brick lined with planks.

East Wood Arch is the simpler, with a low raking parapet above a semicircular arch, a single cross-vault inside with benches at each end in shallow recesses. Endale Arch -- sometimes referred to as Enterdale Arch in early reports -- has a stepped superstructure rising to a raked coping wth a carved flower at the apex, and a pointed arch. These features, together with the banded stonework in two colors, show Syrio-Egyptian influence. There are two cross-vaults, originally with benches in their recesses, in Endale Arch. Planting on top of the tunnels masks passing vehicles. Both tunnels were started in 1867 and completed the following year.

Meadowport Arch, balancing Endale on the west side of Long Meadow, was begun in 1868 and finished in 1870. Instead of cutting under the roadway perpendicularly, like its predecessor, it is set on a 45-degree angle. This permits a double portal at the lawn end, forming two faces of a square pavilion set diagonally into the embankment. A single bay of semicircular cross-vaulting is buttressed at the corners by piers that sweep outward at the base and are capped by octagonal bonnets with finials. The cornices arch in curves concentric to the extrados of the wide openings, a feature of seventeenth-century Mogul architecture in India, such as the Pearl Mosque in Delhi. The voussoirs alternate in smooth and rough-surfaced blocks of Ohio sandstone. A bench filled the recess facing the east arch but, as in the other examples, it has been removed. The northwest end of the wood-lined tunnel has a single face of similar design.

Contemporary with Meadowport Arch is Nethermead Arches, at about the geometric center of Prospect Park. Three segmental-arch spans, four bays deep, constitute a bridge for Central Drive. The three sections serve as underpasses for pedestrians, equestrians, and the Ravine brook between. Nethermead Arches was built of Ohio sandstone with Quincy granite trim. A plain molding constitutes a necking below the springing of the arches, and cylindrical buttresses on square plinths and with pinnacles are set in front of the piers. A parapet pierced by trefoils makes a railing for the upper carriageway and terminates in a monumental pedestal at each end. The inner vaults are faced with hard brick laid in patterns and open laterally into one another.

The last of the underpasses was built in 1871-72. Called Cleft Ridge Span, it is at the east end of Hill Drive, near the Camperdown Elm. Unlike the others, this tunnel is built of molded blocks of concrete, known as Beton Coignet, consisting of sand, gravel and Portland cement. Three colors are used, a brownstone red, ochre, and pale gray. The relief pattern of the sheathing inside the vault is rich and satisfying. The external design is eclectic and somewhat precious in detail. Buttresses flanking the round arches are accented with urns at base and summit, once containing plants. These have suffered from erosion and mutilation, especially on the south side of each facade. The French process provided a less expensive material than stone. Olmsted-Vaux plans of the late 1860's and early 1870's indicate that there were to have been additional pedestrian arches under or over the drives on the west side of the park, but only the ones described were built, all completed while the designers were still in charge.

Perhaps the most practical building in the park was the Well House, built in 1869 on the lake side at the foot of Lookout Hill. It is a rectangular building of banded croton brick and gray Ohio stone, with stone quoins and stone lintels over the windows and Tudor-arched doorway, and overhanging hipped roof. It housed the steam machinery and boiler, that were connected with the pumping engines 60 feet below grade. The engines could raise 750,000 gallons of water a day into the reservoir built into the west end of the hill.

From here the water flowed out of a simulated spring at the base of Quaker Hill and down a gully into Swan Boat Lake, thence through the Ravine to the Lullwater and into the Lake. The source of water was a well 70 feet deep and 50 feet in diameter at the bottom, the walls battering in 10 feet at the top. It was in front of the boiler house, and a square smokestack 60 feet tall was attached to the rear corner. The digging of the Lake was accomplished in intervals. The last section was finished and filled with water 20 August 1871. The original use of the Well House came to a close with the advent of city water into the park about the turn of the century, after which the smokestack was torn down and the well covered over. Lookout Hill reservoir was filled in during the 1930's.

A building of all stone walls erected in 1869 was the Dairy and it was similar to its equivalent in Central Park. It stood in the Midwood, just north of Boulder Bridge over the bridle path. The Dairy was composed of two parallel wings having gables with bargeboards at each end in front, and a connecting unit with a dormer and cupola atop the steep roof. It contained a large public room and smaller ladies' retiring room, both with fireplaces, and facilities on the first floor. Quarters for a family in residence were upstairs. The Dairy supplied light refreshments, including milk, chilled or warm from the cow, because cattle, and sheep as well, were pastured on the Green. The old menagerie was built to the north and east of the Dairy after Olmsted and Vaux had left the scene of tho park. The entire group was razed following completion of the new zoo in 1935, the loss of the Dairy, at least, being regrettable.

It is significant that the small area in Prospect Park conceived along the formal lines of European gardens -- as opposed to the vast balance, which is in the natural Chinese-inspired, English-park mode -- although labeled "Concourse for Pedestrians," was otherwise left blank on the original plan of 1866. That it was intended as a haven for music is indicated by the words "Music Stand" alongside the small island off shore. The region referred to was elaborated in 1870. Olmsted and Vaux testified that they followed an Old-World precedent in their scheme here. "Promenade concerts are common in many European pleasure grounds," they said, and "may be divided into two classes: those universal in German towns, common in French, and less so in British, where the audience is standing, walking, or sitting upon chairs, and frequently at tables at which refreshments are served, and those in which the greater part of the audience is in carriages," as in Italy. They proposed to combine the two types in Prospect Park. The Pedestrian Concourse is situated between two carriage concourses. The latter take care of listeners preferring the Italian manner, whereas the former required renovation to accord with north-European tastes. The middle section was divided into two plateaus by a curved terrace concentric to the shore line and centered on the music stand on the islet. Trees were planted in uniform rows in the lower space; and beyond the stone piers and railings and stairs, on the upper terrace, there was laid out a fan-shaped system of walks radiating from the music source, with fountains at the intersections and a casual growth of trees in the interspaces. This henceforth was known as the Concert Grove. Sculptured likenesses of musicians were placed here, the group including busts of von Weber and Grieg on the east side, Mozart and Beethoven on the west, and that of Thomas Moore, poet, composer and concert pianist, in the center. The United German Singers of Brooklyn presented the images of their countrymen, won as competition prizes during the 1890's.

At the farther end was built a typical Vaux chalet called the Concert Grove House. It resembled the contemporary Dairy, only it was frame instead of stone. The building housed a restaurant and comfort station.

Fifty feet to the south was erected a shelter called the Concert Grove Pavilion, completed in 1874. The Pavilion consists of eight cast-iron posts, modeled after Hindu columns of the early medieval period (8th-12th centuries), supporting a complex hipped roof with rounded corners, measuring 40 by 80 feet, having patterns on its surfaces and a cresting along the ridge. Tables and chairs were placed under this oriental parasol for service from the restaurant. Thus in providing a pleasant retreat for strolling, parking space for carriages, benches, and seats around refreshment tables, the concert compound met all the listening delights of the Europeans; and it went even further: the music was available to boating parties drifting on the Lake. In its formality and function, Concert Grove in Prospect Park is the counterpart of the Mall in Central Park. However, Concert Grove has none of the axial rigidity of the Mall. Instead of being elongated and dividing the park, it is compact, and its radial plan is dynamic, thereby being better suited to the natural landscape theme of the garden as a whole.

Apparently the acoustics around the insular Music Stand were satisfactory only over the water, and concerts soon moved out of the area. A temporary music pavilion was set up in the Lullwood in 1871, and the permanent Music Pagoda was built near the Lily Pond in 1887. This octagonal structure has a high battered podium of rough stonework, above which rise slender posts slanting inward and connecting with the flaring roof. The form suggests an ancient Chinese city gateway. With the establishment of the new Music Grove at the north edge of the Nethermead, its predecessor became known as the Flower Garden. Concert Grove House was demolished in 1949, and Concert Grove Pavilion later was vulgarized by the insertion of a brick snack bar in the middle. The skating rink built in 1960 obliterated Music Stand Island and a stretch of the shore.

A curiosity dating from the Olmsted-Vaux period was a kiosk known as the Camera Obscura, situated at the west end of Breeze Hill. It provided -- as its name signifies -- a dark chamber, in which was a white table five feet in diameter. On the table was projected an image reflected from a revolving mirror-lens arrangement in the roof. The view necessarily was limited to the vicinity. The Old Fashioned Garden later occupied the site. Another oddity of the early era was the Circular Yacht, a sort of water carousel, propelled by sails and oars, that revolved without really going anywhere. As one would expect, the Circular Yacht was not prominently displayed on the Lake but set afloat on the Pool, eventually dammed and enlarged into Swan Boat Lake. Neither of the novelties survived into the twentieth century. The cost of the park during the seven-year administration of Olmsted and Vaux was tremendous. The land alone had cost more than $4,000,000. Improvements amounted to upwards of $5,000,000, the equivalent of almost $25,000,000 in terms of the market value of the dollar today. Prospect Park was the largest single investment made by the City of Brooklyn up to that time, and it is unlikely that any, before or since, has reaped such high dividends in profits of intrinsic value. Olmsted and Vaux's sway of influence went beyond the park confines to related axes and areas. That most closely connected with Prospect Park is the plaza at its main entrance. The elliptical plaza received encouragement in 1867 through the gift to the City of a bronze statue to be erected here. Modeled by the late Brooklyn sculptor, H. K. Brown, it was a standing likeness of Abraham Lincoln, nine feet tall. The figure wears a cape and holds a scroll of the Emancipation Proclamation, the right hand pointing to the words, "Shall Be Forever Free." Probably the first memorial to the assassinated president, it was the gift of the War Fund Committee of Kings County. Elevated on a 15-foot granite pedestal, it was placed on the platform at the north side of the Plaza. The Lincoln statue was dedicated 21 October 1869, and two years later a fountain was put into operation in the center of this open area. The designers widened Vanderbilt and Ninth avenues to 100 feet, and also broadened 15th Street, Coney Island Road (Prospect Park Southwest) and Franklin (Parkside) Avenue. Sidewalks contiguous to the park were to be gaslighted for public strolling "after the gates [of Prospect Park] are closed at night." Olmsted and Vaux pointed out that natural landscape parks in the midst of large cities could not be made safe after dark by lighting them with contemporary equipment and that their "use for immoral and criminal purposes more than balances any advantages" that might be derived from them. The exception was in winter, when the frozen lake was illuminated and temporary houses erected to accommodate the numerous skaters who came there. In summer the external promenades, they felt, took care of the need for nocturnal exercise. The separate Parade Ground was for a different sort of diversion, for observing rather than participating on the part of the public. The State provided for the tract in 1868, and the landscape architects submitted a plan at that time. The 40-acre field adjoins Park Circle, its longer side extending along Franklin (Parkside) Avenue. The larger part of it became a "Green Sward," or lawn, for drills, and at the irregular west end was a graveled area for spectators. The first scheme called for a couple of small structures to be built here, but in 1869 a single long building was constructed instead. It was a wooden affair of exposed framing in the manner of the Concert Grove House, with steep, picturesque roofs. The central pavilion was two-storied, for officers' quarters, and open shelters to either side each extended out 50 feet to a terminal block; that at the south end was a lavatory and that at the north a guard room. The Parade Ground now has become an athletic field for bowling on the green, football, baseball and tennis. Olmsted and Vaux recommended that the city-owned land alongside Prospect Hill Reservoir -- no longer considered for inclusion in the park -- could be utilized for "Museums and other Educational Edifices." After Eastern Parkway was laid out, the Brooklyn Museum was built to the east of the reservoir in the mid 1890's and, on the other side, a section of the Brooklyn Public Library was built about the same time but was replaced by the present building, which was under construction from 1912 to 1941. The balance of the area to the south, between Flatbush and Washington avenues, became the Brooklyn Botanic Garden in 1910. The Administration Building, built a few years later, like the Brooklyn Museum, was designed by McKim, Mead and White. During the depression year of 1873, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux dissolved partnership. It was not a permanent break, because 15 years later they were to collaborate again on a plan for Morningside Park, above 110th Street in Manhattan. Vaux quitted Prospect Park and took up the practice of architecture, building the first pavilion of the Museum of Natural History on Central Park West at 79th Street in 1874, and the first wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Central Park on Fifth Avenue at 83rd Street several years later. Both of these structures can be found today, at the rear of the present groups. Olmsted, in 1873, was appointed Commissioner of the New York Department of Public Parks, and, in Brooklyn, due to the financial crisis, his former position was dissolved and he was retained only as consultant. He kept his post in New York until the beginning of 1878, at which time he left for Europe. Upon his return to America, the center of his activities shifted to New England, and in 1883 he established his home in Brookline, Massachusetts, and his practice in Boston. As for Prospect Park, the team had made its memorable contribution in devising a magnificent and appropriate design and in directing its development up to the time of the depression, and it fell into the hands of others to further, to maintain, and to change -- sometimes to spoil -- the masterpiece that Olmsted and Vaux had created. For the next 18 or 20 years, however, the general tenor of improvements in Prospect Park was channeled in the Olmsted-Vaux tradition. The oldest existing building put up after the designers had severed all connections with the park was utilitarian, and it fitted in with the plan of moving the commissioners into nearby Litchfield Villa. Reference is made to the two storied brick stable built in 1882 on the west side of the park opposite 7th Street, in the center of the present shop group, southwest of the quadrangle. The walls are divided into three bays on the ends and six on the flank, originally with large windows or doors in the first story. The low hip roof was covered with slate. The stable provided for 20 horses and storage of a quantity of hay. A carpenter shop was erected west of it about the turn of the century, a "Queen Anne" style building with half-dormers breaking through the eaves, skylights in the flat middle plane of the roof, segmental arches to the voids, and brickwork set in checkered and chevron patterns. A neighboring structure erected about coeval, with the stable was the great Conservatory, that attracted visitors from as far away as Boston for the Easter lily display in the form of a cross. Its function was taken over by the Brooklyn Botanic Garden greenhouses built in the latter half of the second decade of this century; and, although renovated in 1929-30, the Prospect Park Conservatory was razed in 1955 because its upkeep was considered an unnecessary expense. Public facilities in the park were first provided for ladies at the Dairy, finished in 1869, and later in the appendage to the Promenade Drive Shelter (site of the Peristyle) off Parkside Avenue (men could use the lavatory on the Parade Ground), and for both sexes in Concert Grove House. In 1872, six iron urinals were imported from Glasgow. Of the three set up for immediate use, two were at the Plaza entrance and the other near the 3rd Street entrance. They were supplied with running water and connected with the sewer. The earliest masonry building erected exclusively as a comfort station is between East Wood Arch and the later Boathouse. This "men's closet" -- as it was referred to in the Commissioners' Report of 1888, when it was under construction -- is built of stonework resembling that of the contemporary Music Pagoda, which has been discussed. The building has arches of red brick over doors and windows; it is cruciform in plan and somewhat depressed into the ground to render it inconspicuous, and it is crowned by a moderately steep hipped roof. The two foremost bridges in Prospect Park date from 1890. The first of these replaced Lullwood Bridge, the foundations of which were laid in 1868, and the superstructure built two years later. It had a middle span of 30 feet and two outer spans of 13 feet each, all of oak. The replacement is known as Lullwater Bridge, and it has stone abutments and a single arch of steel. Reliefs ornamenting the sides have been stripped off and the railings simplified. It is for pedestrians only, having steps at each end.

The second and greater structure is Terrace Bridge, which carries the traffic of Hill Drive across the straits connecting the Lake and Lullwater. As its name signifies, Terrace Bridge was meant to be an integral part of the landscaping about the unrealized Refectory. A photograph of the first temporary span here, taken in the early 1870's, shows a rickety open framework of timber. The later permanent bridge of 1890 is substantial, having abutments of brownstone. It has buttresses and bonnets to the piers suggesting forms of Meadowport Arch, and circular plaques on the sides of the stonework inscribed with the date of erection in large numerals. The roadway over the gorge is carried on six steel arches side by side, the outermost enriched with spandrel panels. A parapet the length of the bridge is pierced by a row of little lobed arches. The scale of Terrace Bridge was prophetic of a grandeur that was to appear at and modify Prospect Park over the next 35 years. During the early 1890's, the Soldiers and Sailors' Monument to Civil War Union forces was erected on Grand Army Plaza. The architectural design was by John H. Duncan, who, a few years before, had designed and built Grant's Tomb on Riverside Drive in New York, and the sculpture by Frederick William MacMonnies (1863-1937), a native of Brooklyn, who had apprenticed to Augustus Saint-Gaudens for four years before going to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris to complete his studies. Taking the form of a Roman triumphal arch, the monument was abreast of the times by being in the latest Neo-Classic style, then crystallizing in the renowned "White City" -- the exhibition halls of the World's Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1892-93.

As we have seen, the great elliptical plaza figured in Vaux's sketch of 1865, and it subsequently became the setting for the Lincoln statue and a fountain. The materialization of a triumphal arch with quadriga on top and army and navy groups below was not out of place here, and it was complemented by a pair of Doric shafts, capped with bronze eagles, stationed to either side of the park entrance, also by Duncan and MacMonnies. To further the impressiveness of the Plaza, the architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White was called in to expand the scheme. The three men had served on the Architectural Commission for the World's Columbian Exposition and designed Agricultural Hall and the New York State Building; and, incidentally, they had become associated with MacMonnies and Olmsted at the fair, the sculptor having fashioned the Columbian fountain, and Olmsted having conceived the landscaping. Messrs. Charles Follen McKim (1847-1909) of Pennsylvania, William Rutherford Mead (1846-1928) of Vermont, and Stanford White (1853-1906) of New York set up two more identical pillars, at the Flatbush Avenue and Prospect Park West corners, thus achieving four evenly spaced uprights. They devised curved sections of pierced wall of granite, each ending in pedestals supporting bronze urns, to form a unifying background. Inside the park, near the outer columns, were built two 12-sided pavilions of the Tuscan order, also of granite, containing semicircular benches, and slab screens in six intercolumniations at the back. These pavilions have low-pitched pyramidal roofs capped by bronze finials. The elegant ensemble was completed in 1895. Meanwhile, Frederick MacMonnies had modeled the lifesize bronze figure of James S. T. Stranahan that was installed on a pedestal to the east side of Main Entrance Drive in 1891, honoring the man who had taken the greatest interest in the park, and it is fitting that Mr. Stranahan attended the dedication.

The second most important portal to Prospect Park is on Park Circle, at the south corner, nearest the Lake. The principal motif here is a pair of bronze lifesize equestrian groups, each composed of two horses and a male nude rider, by MacMonnies. Called The Horse Tamers, we are reminded of Coustou's Horses of Marly, the eighteenth century sculptures in the Place de la Concorde, Paris. The horses in Brooklyn are wilder; their ruthless spirit challenges the tamers to remain mounted without benefit of saddles, and the tortured outlines of the forms approach the chaotic. Like the Grand Army Plaza figures, these pieces were modeled in Paris and cast at the LeBlanc-Barbedienne Foundry. The architectural setting on Park Circle again is by McKim, Mead and White, consisting of 19-foot granite pedestals embellished with reliefs in both stone and bronze, walls concentric to the circle interrupted by pedestrian entrances flanked by broad urns, and square end pavilions with corner piers and distyle Greek Ionic columns in antis in each side, covered by low pyramid roofs. The architects proposed four tall granite columns surmounted by bronze eagles to be stationed in back, but these were not included in the 1896-97 construction. The contemporary Willink Entrance, on Flatbush Avenue near the junction of Ocean Avenue and Empire Boulevard, was named after the family whose old home stood in this vicinity. McKim, Mead and White flanked the drive with twin granite turrets, 20 feet tall, having waist-high bases, plain cylindrical shafts, bonnets enriched with imbrication, and bronze urn finials. Wall segments of base height, with benches set in front of the four sections, terminate at circular sentry boxes, spaced 200 feet apart, and, from these, convex walls curve out to the street. The round boxes originally had hinged doors and glazed windows. They relate to the octagonal granite police kiosks in the park, such as those near the Grand Army Plaza, Park Circle and 3rd Street entrances. The gateway at 3rd Street and Prospect Park West is guarded by a pair of bronze panthers modeled by Alexander Phinnister Proctor. The sculptured animals were set on tall rectangular granite shafts in 1897. Perhaps the most inviting entrance is that at the obtuse angle of Parkside and Ocean avenues, also by McKim, Mead and White. A curved granite colonnade of two sections is divided by the driveway, and a walk enters park from the center of each unit. Square end piers are coupled with round Roman Ionic columns, and two pairs of similar columns are between. Screens run along the park side, with benches in front. The colonnades support an open timber trellis clad with wisteria. The curve of the plaza continues beyond Ocean Avenue, forming a half-circle, but does not cross Parkside Avenue. This entrance was realized in 1904. A companion to this pergola, built by the same designers and at the same time, is the Classic Peristyle, below South Lake Drive and across from the east end of the Parade Ground. It superceded Promenade Drive Shelter, of the late 1860's, a 200 by 35-foot frame structure covered by a canopy and appended to which was a small comfort station. The new pavilion consists of a low platform and a colonnade, with square corner posts and alignments of Corinthian columns between, four in each end and ten on the flank. The supports are of limestone up to the capitals, which, with the entablature, are of whitish terra cotta. Architrave blocks are wedge-shaped, like voussoirs: of a flat arch, and the frieze is filled with a continuous relief of luxuriant foliage. Attic blocks, on axis with the columns, and intervening balustrades surmount the console cornice. The Peristyle sometimes is called the Grecian Shelter, which is a misnomer inasmuch as all of its features are in the Renaissance manner.

The monumental gateways opposed the Olmsted-Vaux tradition by introducing architectural features at the entrances, originally elaborated only by rows of evenly spaced trees -- continuous with those of the promenades that encompass the park -- and two small rustic pavilions on the Plaza to serve as shelters for people alighting from or waiting for cars. The McKim, Mead and White gateway additions at least faced out, relating themselves to the city beyond, whereas the Peristyle is wholly inside the park, thus representing a different viewpoint. it was succeeded by three larger structures in the same manner. They were the work of the architectural concern of Helmle, Huberty and Hudswell. Frank J. Helmle (1868-1939) had come from Ohio and studied at Cooper Union and the Brooklyn Museum School of Fine Arts. In 1890 he joined the staff of McKim, Mead and White, and the next year formed a partnership with Ulrich J. Huberty. Their first building in Prospect Park was the Boathouse, on the east side of the Lullwater. It was built in 1905 to replace the old wood shed boathouse around to the north, at the mouth of the brook. Like the upper parts of the Peristyle, the new Boathouse was built in its entirety of white mat-glazed terra cotta, the roof covered with red tile. An arcade along the water front has engaged Tuscan columns set before the piers, and an entablature with triglyphs is surmounted by a balustrade. The design was borrowed from the lower story of Sansovino's Library of St. Mark, of the sixteenth century, in Venice. The first story originally was open. Double staircases rose from the middle of the building to landings on the east wall, whence twin flights came together at a higher landing and a single flight continued to the second floor inside a semicircular well. The stairs embraced a boat-renting office on the main floor, and there was an enclosed kitchen at the north end, and a soda fountain and ladies' rest room at the south. The second story was a dining hall, served by dumbwaiters in the two east corners. French doors opened onto the balustrated terrace. Twenty bronze lampposts with dolphin motifs are spaced along the broad flights of granite steps descending to the landing and continue around the ends of the building. A flimsy open shed intruded upon the landing terrace in 1915.

The second Helmle and Huberty building is the Tennis House, constructed in 1909-10 on the west side of Long Meadow, halfway between Swan Boat Lake and the park shops and stables. It provided lockers for participants in the growing sport of lawn tennis, earlier using the basement of the 1885 carousel in Picnic Woods. Built of limestone and yellow brick, on granite foundations, and with terra-cotta vaults and a red tile roof, the Tennis House, like the Boathouse, is classic in style and achieves an intimacy with the park through being predominantly open. The characteristic motif is the triple void, the centermost arched, a favorite with the influential sixteenth century Italian architect, Andrea Palladio, whose name it bears. The casino quality of the Tennis House is not unlike that of the elegant mid-eighteenth-century Palladian Bridue in Prior Park at Bath, England, an entirely fitting accent for a natural landscape, according to high British taste of the period. Only to a slightly lesser degree can the same English monument be compared with the two preceding pavilions in Prospect Park. Although the original designers would not have approved of their existence in this idylic retreat, at least there is basis for a respectable argument to be used in their defense.

The third detached building in Prospect Park by the Helmle firm is the Willink Entrance Comfort Station, built in 1912. Like the Tennis House, it is constructed of limestone and yellow brick and has a red tile roof. Wash rooms at either end are connected by a vaulted breezeway supported on each side by Tuscan columns in five pairs, set one behind the other. Twin chimneys rise hipped roof and deep eaves overhang the Willink Comfort Station is less classical than its forerunners and forecasts the expiration of the the style from Prospect Park. Later buildings, at most, were to show isolated related details, and these not in very good scale with the buildings to which they were attached. Even during the quarter of a century preceding the First World War, there were improvements put into the park that were in no wise Neo-Classic. Two examples were erected on the Peninsula, and both had a strong flavor of Olmsted-Vaux park architecture about them. The first one was on the south shore, equidistant between the Landing Shelter and Well House. It was the Model Yacht Club House, in which miniature ships were kept for sailing on the Lake. It was a cruciform frame building, with an octagonal superstructure providing clerestory lighting at the crossing. This unostentatious clubbouse was built in 1900, and it burned in 1956, together with its cherished contents. Only the landing terrace in front remains. The miniature-boat enthusiasts were relocated in the abandoned Well House. The second structure was directly across the Peninsula, or midway between the Model Yacht Club House and Terrace Bridge. Here was a low, sprawling shelter with gently sloping roofs and deep overhanging eaves, including a long breezeway between end pavilions, the gables of which jutted through the hipped roof. Despite the difference in roof pitch, the style of the structure related to that of Concert Grove House. Its rustic parts were of cedar and the roofing was of chestnut slabs. Although built 15 years after its companion, the shelter disappeared first. Both are regrettable losses to the park. During the second decade of the century the stable quadrangle was built between the existing utility-conservatory group and West Drive, on a line with 6th Street. Although the largest structure erected in Prospect Park up to this time, its simple lines, low masses and semi-isolation make it an acceptable addition to the complex. Its brick walls are articulated with arches; a porte-cochere leading into the courtyard and a small belfry lend interest to the design.

Two fine classic monuments, that will reward our consideration before leaving this era, are located on the west perimeter of the park. The first is at the entrance on Bartel-Pritchard Circle. It consists of a pair of giant pillars of such uniqueness as to be a noteworthy landmark. The source of inspiration was the little-known Acanthus Column of Delphi, a votive shaft dating from the beginning of the fourth century B.C. In using it for a model, Stanford White made the most of its best features and improved its proportions, achieving a more substantial foundation and a less topheavy summit. The result is an exquisite form, which, if one did not know of its antique archetype, one would attribute it to a stroke of genius on the part of a designer of the classic-eclectic period. Set on a high square plinth, each shaft is banded at the base, above which is a campaniform carved with a frieze of Greek anthemion. Four girdles of acanthus leaves alternate with four fluted drums and the whole is crowned by a flaring acanthus capital. A bronze tripod of utmost simplicity is atop the shaft; the sculptured caryatids supporting the urns in the original are eliminated without any suggestion of incompleteness. Stanford White conceived the pillars in 1906, the year he was killed, and one is prompted to look upon the granite uprights as a testimonial to his impeccable artistry.

Six blocks to the north, facing 9th Street at Prospect Park West, stands the stele honoring the Marquis de Lafayette, French statesman and soldier, who took up the cause of American freedom during the Revolution. The Lafayette Monument presents a lifesize image of the general in the round engaged to a low-relief background representing horse and groom. The bronze plaque was the work of Daniel Chester French (1850-1931), sculptor of the colossal Republic at the Chicago Fair, of the two allegorical figures of New York and Brooklyn from the Manhattan Bridge now at the entrance to the Brooklyn Museum, and later he was to execute the seated marble portrait in the Lincoln Memorial in Washington. His tribute to Lafayette is elevated on a granite podium and enframed by Corinthian pilasters styled after the order of the first-century B.C. Tower of the Winds at Athens. These columns have an unusual capital of a single row of acanthus leaves above which rises a ring of flattened grasses clinging close to the campaniform. The Athenian example has no base, but the pilasters of the Lafayette Monument have normal footings. It was dedicated 10 May 1917; the ceremony included Mme. Louise Homer singing La Marseillaise and The Star-Spangled Banner, accompanied by her husband at a small piano provided for the occasion.

The United States had been several months at war when the patriotic demonstration was made coincident to the dedication of the Lafayette Monument. As in the Civil War period, little happened in Prospect Park throughout the First World War. The initial addendum afterwards was -- as might be feared -- a memorial to those slain in the service of their country. Called the Honor Roll Memorial, placed by the side of the Lake between Music Island and the Landing Shelter, it features a semicircular granite wall bearing six bronze tablets inscribed with the names of Brooklyn victims of the war. An heroic group in the center represents the winged Angel of Death and the Soldier. A pedestal is in front, seats are to either side, and a circular altar stands in the middle. The shrine was erected in 1920. Arthur D. Pickering was the architect, Augustus Lukeman the sculptor with Daniel Chester French as associate. Although the magnitude and design of the memorial are inoffensive, it is a reminder of the tragic consequences of violence that would have a more sympathetic setting in a cemetery; and it ushered in an era of building in the park in which the basic concepts, in one way or another, were as inappropriate as here and likewise should have sought sanctuary elsewhere. In 1927 a new and larger Picnic House was built to replace the older one on the same site, on Long Meadow behind Litchfield Villa and just north of the old carousel. The raised-basement type building of red brick has a projecting entrance block with frontal steps between antepodia, a Palladian arch to the recessed entrance set on a pair of insignificant Ionic columns and crowned by a harsh gable. Details are thin and poorly conceived of manufactured stone. Fenestration is oversized, and the hipped roof, covered with red tile, is steep and heavy. A large assembly hall is on the main floor, and rest rooms, utilities and a lunch counter are in the basement. The architect was J. Sarsfield Kennedy. Picnic House now serves as a Golden Age Center. It resembles a rural schoolhouse of the roaring twenties, an awkward, prosaic, cubic pile, which the graceful sweep of Long Meadow could very well do without. West of the colonnade at the Ocean Avenue Entrance, near Parkside Avenue, stands a severely rectangular little comfort station with the classic divisions of basement, first story and parapet clearly defined. The central portal is higher, with urns set atop corner piers and an arched doorway. Fenestration is restrained. The building has the virtue of being small, and some attempt has been made to relate it in style to the early twentieth-century buildings in the park. The architect was Kennedy, and it was built in 1930.