|

New York

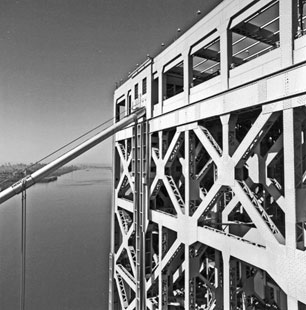

Architecture Images-New York Bridges George Washington Bridge |

|||

| Contemporary black and white images on this page copyright Dave Frieder ( www.davefrieder.com ). Special thanks to Dave Frieder for permission to use images. | ||||

|

architect |

Othmar Ammann, Cass Gilbert | |||

|

location |

between northern Manhattan and New Jersey | |||

|

date |

1927-31 | |||

|

style |

Structural Expressionism | |||

|

construction |

steel | |||

|

type |

Suspension Bridge | |||

|

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

images |

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

| Dave Frieder Gallery. Copyright Dave Frieder ( www.davefrieder.com ) | ||||

|

||||

| The "Little Red Lighthouse" under the George Washington Bridge in New York City, NY. | ||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

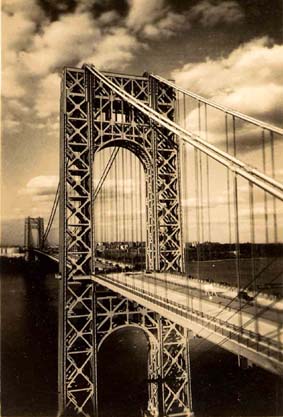

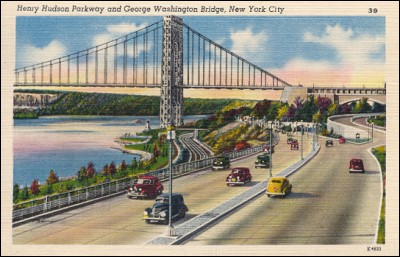

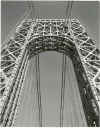

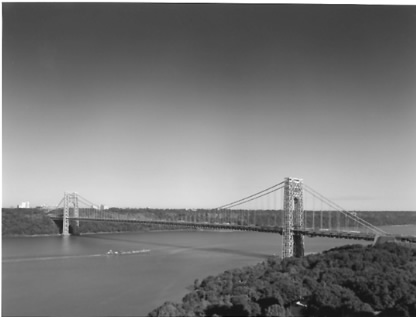

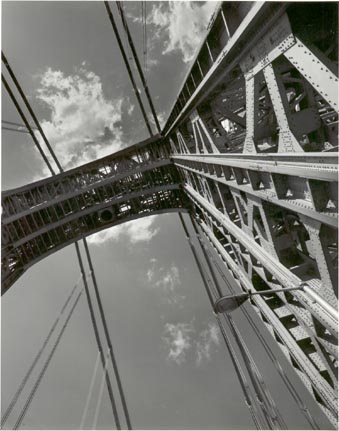

The George Washington Bridge (known informally as the GW Bridge[3], the

GWB[4], the GW[5], or the George[6]) is a suspension bridge spanning the

Hudson River, connecting the Washington Heights neighborhood in the

borough of Manhattan in New York City to Fort Lee in New Jersey by means

of Interstate 95, U.S. Route 1/9. U.S. Route 46, which is entirely in

New Jersey, ends halfway across the bridge at the state border. The GW

is considered one of the world's busiest bridges in terms of vehicle

traffic;[7] In 2004, the bridge carried 108,404,000 vehicles, with

current AADT estimates of nearly 300,000 vehicles daily. The GW span is

the fourth largest suspension bridge in the United States. The bridge contains two levels, an upper level with four lanes in each direction and a lower level with three lanes in each direction, for a total of 14 lanes of travel. Additionally, the bridge houses a path on each side of the bridge for pedestrian traffic. The speed limit on the bridge is 45 mph (70 km/h), though heavy traffic is common and frequently makes it difficult to reach such speeds. History Groundbreaking for the new bridge began in October 1927, a project of the Port of New York Authority. Its chief engineer was Othmar Ammann, with Cass Gilbert as architect. The bridge was dedicated on October 24, 1931, and opened to traffic the following day. Initially named the "Hudson River Bridge," the bridge is named in honor of George Washington, the first President of the United States. The Bridge is near the sites of Fort Washington (on the New York side) and Fort Lee (in New Jersey), which were fortified positions used by General Washington and his American forces in his unsuccessful attempt to deter the British occupation of New York City in 1776 during the American Revolutionary War. In 1910 the Washington Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution erected a stone monument to the Battle of Fort Washington. The monument is located about 100 yards northeast of the Little Red Lighthouse, up the hill towards the eastern bridge anchorage. When it opened, the bridge had the longest main span in the world; at 1,067 m (3,500 ft), it nearly doubled the previous record of 564 m (1,850 ft), which had been held by the Ambassador Bridge. (The record has since been exceeded numerous times.) The total length of the bridge is 1,451 m (4,760 ft). As originally built, the bridge offered six lanes of traffic, but in 1946, two additional lanes were provided on what is now the upper level. A second, lower deck, which had been anticipated in Ammann's original plans, was added, opening to the public on August 29, 1962. This lower level was waggishly nicknamed "Martha" by some. The additional deck increased the capacity of the bridge by 75 percent, making the George Washington Bridge the world's only 14-lane suspension bridge, providing eight lanes on the upper level and six on the lower deck. The original design for the towers of the bridge called for them to be encased in concrete and granite. However, due to cost considerations during the Great Depression and favorable aesthetic critiques of the bare steel towers, this was never done. The exposed steel towers, with their distinctive criss-crossed bracing, have become one of the bridge's most identifiable characteristics. Le Corbusier (Charles-Edouard Jeanneret) said of the unadorned steel structure: "The George Washington Bridge over the Hudson is the most beautiful bridge in the world. Made of cables and steel beams, it gleams in the sky like a reversed arch. It is blessed. It is the only seat of grace in the disordered city. It is painted an aluminum color and, between water and sky, you see nothing but the bent cord supported by two steel towers. When your car moves up the ramp the two towers rise so high that it brings you happiness; their structure is so pure, so resolute, so regular that here, finally, steel architecture seems to laugh. The car reaches an unexpectedly wide apron; the second tower is very far away; innumerable vertical cables, gleaming against the sky, are suspended from the magisterial curve which swings down and then up. The rose-colored towers of New York appear, a vision whose harshness is mitigated by distance." (When the Cathedrals were White", 1947.) Following the September 11th attacks on New York and Washington, the Port Authority prohibited people from taking photographs on the premises of the bridge due to the fear that terrorist groups might study any potential photographs in order to plot a terrorist attack on the bridge. As the enclosed lower level is more vulnerable to hazardous material (HAZMAT) incidents than the upper level and most HAZMATs have been prohibited there even before the September 11th attacks, all trucks have also been banned from the lower after the September 11th attacks due to the fear that concealed HAZMATs could cause major incidents.[citation needed] The George Washington Bridge is home to the world's largest free-flying American flag. The flag, located under the upper arch of the New Jersey tower, drapes vertically for 90 feet (27 m). The flag's stripes are about 5 feet (1.5 m) wide and the stars measure about 4 feet (1.2 m) in diameter. Weather permitting, the flag is flown on Martin Luther King Day, President's Day, Memorial Day, Flag Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Columbus Day, and Veterans Day, as well as on dates honoring those lost in the September 11, 2001 attacks.[8][9] Road connections George Washington Bridge, Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) collections.The George Washington Bridge carries I-95, US-1, and US-9 between New Jersey and New York. US-46 terminates at the state border in the middle of the bridge. I-80 and NJ-4 also feed into the bridge but end before reaching it. On the New Jersey side of the Bridge, the Palisades Interstate Parkway connects directly to the bridge's upper level (there were plans to give direct access to the lower level from the parkway but the plan has been postponed), and the New Jersey Turnpike connects to both levels of the bridge. On the New York side, the twelve-lane Trans-Manhattan Expressway heads east across the narrow neck of upper Manhattan, from the bridge to the Harlem River, providing access from both decks to 178th Street, the Henry Hudson Parkway and Riverside Drive on the West Side of Manhattan, and to Amsterdam Avenue and the Harlem River Drive on the East Side. The Expressway connects directly with the Alexander Hamilton Bridge, which spans the Harlem River as part of the Cross-Bronx Expressway (I-95), providing access to the Major Deegan Expressway (I-87). Heading towards New Jersey, local access to the Bridge is available from 179th Street. There are also ramps connecting the bridge to the George Washington Bridge Bus Terminal, a commuter bus terminal with direct access to the New York City Subway at the 175th Street (A) station on the IND Eighth Avenue Line. Tolls Night View of GWB from GE Building.Current tolls for cars are as follows: $6 if paying with cash, $5 peak hours with E-ZPass, and $4 off-peak hours with E-ZPass. A special discounted carpool toll ($1) is available for cars with three or more passengers, at all times, with E-ZPass, who proceed through a staffed toll lane (provided they have previously opted-in to the free "Carpool Plan"). Current tolls for motorcycles are $5 cash, $4 peak hours with E-ZPass, and $3 off-peak with E-ZPass. Trucks are charged $6 per axle, with significantly discounted off-peak and overnight tolls.[10] The toll is only charged one way (eastbound), which is how all Hudson River crossings from are tolled. Foot traffic and cyclists cross for free on sidewalks, one on each side of the upper deck, offering spectacular views of the Hudson River, the Manhattan skyline and the New Jersey Palisades. Pedestrians had to pay tolls of 10 cents shortly after the bridge opened, but non-motorized traffic is no longer tolled. The George Washington Bridge takes in approximately $1 million per day in tolls. In January 2007, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey announced a deal with Geico, the auto insurance giant, that included the posting of a large billboard on top of the toll plaza that said "Geico Drive Safely," and Geico signs on the tollbooths and approach roads, some of which would feature the insurer's signature gecko. The arrangement would have provided the agency with $3.2 million over two years.[11] A week later, however, the Port Authority cancelled the contract with Geico after criticism that the signs would mar the landmarked bridge, that the Port Authority had failed to negotiate a good price for the deal and that the placement of the signs might violate Fort Lee's regulations.[12] Non-motorized access The George Washington Bridge from Riverside DriveThe George Washington Bridge is also popular among sightseers and commuters traveling by foot, bicycle, or roller skates. Normally the North sidewalk is for pedestrians only, and the South sidewalk (accessible by a long, steep ramp on the Manhattan side of the bridge) is shared by bicyclists and pedestrians. The South sidewalk, while requiring a climb / descent of the ramp on the New York side, offers the easiest access for bicyclists, with a level surface from end to end. The South side entrance in Manhattan is at 178th Street, just west of Cabrini Boulevard. The North sidewalk requires stairway climbs and descents on both sides, always an inconvenience and obstacles to handicapped people, and a greater risk in poor weather conditions. The South sidewalk is accessible from the New Jersey side from Hudson Terrace, where an open gate allows pedestrians and bikes to pass. Passing just north less than one hundred yards on Hudson Terrace from the bike/ped entrance, walkers will find the start of the Long Path hiking trail, which leads after a short walk to some spectacular views of the bridge, and continues north towards Albany, New York. From September 12, 2005 through September 2006, bicycle and pedestrian access to the George Washington Bridge was affected by Port Authority construction (tower painting including lead removal). Until June 18, 2006, the North sidewalk was closed for construction and the South sidewalk was open from 6:00 AM to midnight for both pedestrians and bicyclists. From June 19, 2006 to October 13, 2006 at approximately 3 p.m, the North sidewalk was open from 6:00 AM to midnight and the South sidewalk was closed at all times. From October 13, 2006 at approximately 3 p.m, the South sidewalk is open from 6:00 AM to midnight and the North sidewalk is closed at all times. The Port Authority explains that periodically closing either sidewalk is to remove contractor's equipment.[13] Transportation Alternatives, a New York City advocacy group, has proposed an enhanced River Road connector in Fort Lee, which would create safer pedestrian and bicycle access to the George Washington Bridge on the New Jersey side of the bridge.[14] Alternate routes Motorists and trucks traveling from New England states towards Pennsylvania, or from the direction of Pennsylvania towards New England, often take the Tappan Zee Bridge crossing instead of the George Washington Bridge as this effectively bypasses New York City and the associated traffic. The GWB in popular culture The New York side of the George Washington Bridge as seen from the Hudson River, July 2005. The tarp on the tower is from restoration that was taking place at the time. Note the "Little Red Lighthouse."The George Washington Bridge is mentioned in the song "The Cause of Death" by Immortal Technique in a reference to an alleged news report that bombs had been planted on the bridge by four non-Arabs during the September 11, 2001 attacks. The GWB's first movie appearance was in Citizen Kane (1941), and it subsequently appeared in How to Marry a Millionaire, The In-Laws, Desperately Seeking Susan, How To Lose A Guy In 10 Days and Manhattan Murder Mystery. The bridge features prominently in the 1997 movie Cop Land, its lower deck serving as a site for an important early scene and the entire bridge acting as a symbolic barrier between Manhattan and the small towns across the river in New Jersey. A memorable quote from Cop Land is when actor John Spencer speaks into his radio following the apparent suicide of a NYPD police officer: "We've got a man off the [censorship preserved] G.W.!" In a scene in The Godfather (1972), enroute to a dinner meeting at which Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) plans to murder family enemy Virgil "The Turk" Sollozzo (Al Lettieri) and Sollozzo's bodyguard, Police Captain Mark McCluskey (Sterling Hayden), the car in which they are riding is shown heading westbound across the New York/New Jersey state line on the George Washington Bridge. Michael, trying to hide his surprise that the car is not bringing them to the Bronx restaurant at which he plans to commit the murder (and at which a gun has been hidden for his use), asks Sollozzo, "We're going to Jersey?," and Sollozzo cryptically answers, "Maybe." Suddenly Sollozzo's driver, Lou, makes a screeching, harrowing U-turn across the center median, and the car heads back to New York City. In real life, however, the bridge used for filming the U-turn was not the George Washington Bridge, but the Queensboro Bridge over the East River. Harry Belafonte encounters the bridge choked with abandoned cars in The World, the Flesh and the Devil. The bridge's construction is featured in the 1942 children's book The Little Red Lighthouse and the Great Gray Bridge by Hildegarde Swift and illustrated by Lynd Ward (ISBN 0-15-204571-6). In the book, a small lighthouse on the Manhattan shore fears it will be overshadowed and rendered useless by the bridge's tall towers and bright lights—but is reassured that the bridge's lights are for airplanes, not ships. The lighthouse does exist in real life and is currently owned by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. An episode of I Love Lucy concludes with the show's four main cast members beginning a motor trip from New York City to Hollywood, while driving across the George Washington Bridge and singing California, Here I Come. In the film Network, William Holden's character twice tells the story of how, as a young reporter, he was awakened early in the morning to report on an accident on the bridge. His news crew is waiting for him on the bridge. So he hails a cab outside his apartment, and tells the driver, "Take me to the middle of the George Washington Bridge!" And the driver tells him, "Don't do it, buddy! You're young! You've got your whole life ahead of you!" In The Amazing Spider-Man comic books (issue #121), Spider-Man's girlfriend, Gwen Stacy, is kidnapped and held at a bridge by the Green Goblin. The artwork depicts the Brooklyn Bridge, but the editor mistakenly labeled it as the George Washington Bridge. In addition to that, in Spider-Man: The Animated Series Mary Jane is thrown off the George Washington Bridge by the Green Goblin. The bridge also appeared in X-Men as the team approaches the Statue of Liberty. In Across the Universe, the lit-up bridge appears in the background of a shot showing a bus stopping at the George Washington Bridge Bus Terminal. American composer William Schuman wrote The George Washington Bridge for concert band in 1950. The GWB appears in Stephen King's Dark Tower books, both in New York and the city of Lud. In Confessions of a Teenage Drama Queen, the main character and her family drive across the bridge as they relocate from Manhattan to New Jersey. On The Cosby Show, Cliff anticipates his daughter Sondra's moving out of the house, and says to help her leave, he would, "CRAWL across the George Washington Bridge..." Babylon Rising: The Europa Conspiracy, By Tim Lahaye includes a fictional plot to detonate a dirty bomb over the George Washington Bridge. A portion of one of the greatest car-chase scenes on film, The Seven-Ups starring Roy Scheider, takes place on the GWB. Also shown is the bus terminal that is part of bridge complex. In the PlayStation 2 game, Metal Gear Solid 2, The Tanker Chapter starts out with Solid Snake leaping off of The George Washington Bridge onto the USS Discovery. At the conclusion of the Tom & Jerry animated short Mouse in Manhattan, Jerry scrambles over the bridge to return home. In an episode of Everybody Loves Raymond, Ray states that he "ran out of things to say at the George Washington Bridge" to convince Debra that they are a boring couple. He also states that he would take the upper level because if it collapses, he would fall on the people on the lower level. References ^ Port Authority of New York and New Jersey - George Washington Bridge. Retrieved on 2007-09-10. ^ 2005 NYSDOT Traffic Data Report: AADT Values for Select Toll Facilities. Retrieved on 2007-05-05. ^ Rose, Lacey. "Inside The Booth", Forbes, March 2, 2006. Accessed January 15, 2008. "Like the PATH trains, which also connect New York to New Jersey, the G.W. Bridge is run by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, a public agency that employees 7,000 workers and has annual revenues of $2.9 billion." ^ Toolen, Tom. "BRIDGES KEEP PHOTOGRAPHER IN SUSPENSE", The Record (Bergen County), September 27, 1995. Accessed January 15, 2008. "Frieder calls the GWB 'the most beautiful suspension bridge in the world...'" ^ Jones, Charisse. "Upkeep costs rise as USA's bridges age", USA Today, October 20, 2006. Accessed January 15, 2008. "The George Washington Bridge — locals call it 'the GW' — is one of a collection of dazzling spans that link New York's five boroughs or the city and New Jersey." ^ Barron, James. "PUBLIC LIVES; Bridge Photographer With a Taste for Trivia", The New York Times, July 22, 1998. Accessed January 15, 2008. "Mr. Frieder takes it for granted that anyone who has ever heard a radio traffic report will know that the G.W.B., a k a the George, is the George Washington Bridge." ^ George Washington Bridge turns 75 years old: Huge flag, cake part of celebration, Times Herald-Record, October 24, 2006. "The party, however, will be small in comparison to the one that the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey organized for 5,000 people to open the bridge to traffic in 1931. And it won't even be on what is now the world's busiest bridge for fear of snarling traffic." ^ George Washington Bridge, Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Accessed May 28, 2007. ^ George Washington Bridge Interesting Facts, Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Accessed May 28, 2007. ^ Port Authority Toll Rates (reprint 2002), accessed October 22, 2006. ^ The New York Times. "With Ad Deal, Insurer Wades Into Bridge Traffic.", January 4, 2006. ^ Belson, Ken. "Agency Cancels Insurer’s Ads for George Washington Bridge.", The New York Times, January 9, 2007. ^ George Washington Bridge: Pedestrians and Bicyclists Latest update, accessed October 22, 2006. ^ Support Grows in NJ for GW Bridge to "River Road" Connector Path, Transportation Alternatives Magazine, Summer 2003. |

||||

|

The two-level George Washington Bridge (GWB) crosses the Hudson River between upper Manhattan (West 178th Street) and Fort Lee, New Jersey and forms part of Interstate Highway I-95. This suspension bridge was designed by

Othmar H. Ammann who was the Port Authority's Chief Engineer during that

time. Ground was broken for the original six-lane bridge in October

1927. The Port Authority opened the bridge to traffic on October 25,

1931. In 1946, two additional lanes were provided on the upper level. The New Jersey approach system provides connections between both levels of the bridge and highways US-1, US-9W, US-46, NJ-4, I-80, I-95 and the Palisades Interstate Parkway. The twelve-lane Trans-Manhattan Expressway, extending eastward from the bridge to the Harlem River between 178th and 179th Streets, connects both levels of the bridge with Amsterdam Avenue, the Harlem River Drive and the 181st Street Bridge over the Harlem River. The Expressway connects directly with the Alexander Hamilton Bridge, which spans the Harlem River as part of the Cross Bronx Expressway (I-95), and the Major Deegan Expressway (I-87). Both the upper and lower levels connect to the Henry Hudson Parkway and Riverside Drive on the West Side of Manhattan. Sidewalks are available to the general public on both the north and south sides of the bridge. In New Jersey, the sidewalk entrances are located on Hudson Terrace in Fort Lee. In New York, the south sidewalk is located near the corner of 178th Street and Cabrini Boulevard. The north sidewalk is located near the corner of 179th Street and Cabrini Boulevard. Port Authority of NY and NJ GWB page STATISTICS Opened to Traffic Length of Bridge (between anchorages) 4,760

feet "The George Washington Bridge over the Hudson is the most beautiful bridge in the world. Made of cables and steel beams, it gleams in the sky like a reversed arch. It is blessed. It is the only seat of grace in the disordered city. It is painted an aluminum color and, between water and sky, you see nothing but the bent cord supported by two steel towers. When your car moves up the ramp, the two towers rise so high that it brings you happiness; their structure is so pure, so resolute, so regular that here, finally, steel architecture seems to laugh… The second tower is very far away; innumerable vertical cables, gleaming across the sky, are suspended from the magisterial curve that swings down and then up. The rose-colored towers of New York appear, a vision whose harshness is mitigated by distance." - Le Corbusier

WEAVING A GREAT

BRIDGE: Soon after the Port Authority announced

the Hudson River bridge project in 1925, Ammann commissioned consultants

for various designs. Initial plans devised by the Port Authority and the

Regional Plan Association (RPA) called for a suspension bridge with a

2,700-foot-long main span, with piers approximately 400 feet beyond the

pierhead lines. In a revolutionary

shift from prevailing suspension bridge design convention, Ammann

proposed eliminating the stiffening trusses that had been essential for

suspension bridges in an earlier age, when they were designed for heavy

rail traffic. Instead of using trusses, Ammann theorized that as the

weight per linear foot of long-span bridges increased, the deadweight of

the bridge deck and the four cables would be sufficient to resist heavy

wind, thereby eliminating the need for trusses. Each of the

106-foot-long floor beams weighed 66 tons. Even with a single deck only

10 feet deep, and a depth-to-span ratio of 1:120, neither heavy traffic

nor high winds caused the bridge to sway. However, the bridge was

designed to accommodate a second, truss-stiffened deck that could be

added later.

|

||||

|

LEISURE & ARTS A Landmark Destination: The Bus Station  Pier Luigi Nervi's terminal at the George Washington Bridge is a powerful, handsome place, soot notwithstanding. BY ADA LOUISE HUXTABLE Tuesday, June 15, 2004 12:01 a.m.  NEW YORK--A subway ride to MoMA QNS will take you to see the models for Santiago Calatrava's Transportation Hub for the World Trade Center site, a remarkable structure commissioned by the Port Authority of New York that raises technology to the highest level of beauty and utility. They will be on view until Sept. 27. A subway ride to 178th Street and Broadway will take you to see Pier Luigi Nervi's bus terminal at the George Washington Bridge, an equally remarkable structure commissioned by the Port Authority more than 40 years earlier, when the Italian engineer was as celebrated as Mr. Calatrava is now. Mr. Calatrava's models for a terminal yet to be built are ethereally empty and rendered in pristine white; Nervi's terminal, completed in 1962, is deeply discolored with soot and grime. But what separates these two buildings is more than time and distance, or past vs. future; it is New York's short memory. Lavish praise has greeted Mr. Calatrava's glass and steel structure with its ribbed, winglike canopies that admit daylight above and below ground and can be opened to the sky. The same kudos marked the Port Authority's announcement of the Nervi commission, which was also hailed as a visionary act in the early 1960s. Mr. Calatrava's position in the 21st century and Nervi's in the 20th are roughly equal. The two men share an international reputation for turning engineering into art. Both make complex things seem dramatically simple, so the untrained observer can sense with pleasure the play of forces held in equilibrium by elaborate calculations and an impeccable eye. In their talented hands, structural design achieves a rational elegance. Because engineering is the heart and soul of construction--the building's bones on which everything else depends for support and stability--structure trumps style. But style is there--Mr. Calatrava's forms have extraordinary brio; Nervi, who died at 87 in 1979, practiced with a fine Italian hand. Mr. Calatrava's engineering is a kind of 21st century architecture parlante, transcending the utilitarian to mimick the forms of flight. Sometimes his extravagantly expressionistic gestures go overboard, but his soaring bird is spot on for New York, where tragic circumstances and an unparalleled opportunity require a symbolic act of aesthetic daring. If Mr. Calatrava's building is a bird, Nervi's is a butterfly. The bus terminal's rooftop sets of butterfly trusses are echoed in the butterfly entrance canopy that is pure vintage 1960s. In Nervi's structural art, there are no superfluous moves. The beauty of his buildings relies on simple geometry and sophisticated prefabrication. The repeated V-shaped members of the bus terminal's concrete trusses echo the steel cross bracing of the George Washington Bridge. Disturbed by reports from guardians of our modernist heritage that the building had suffered neglect and was threatened by change, I went back recently to see how it had fared. My last visit had been a hardhat climb over the newly constructed building with the maestro himself; no fear of heights could have kept me from the experience. I found a strong, proud and handsome survivor. Nervi still comes through loud and clear. The building is enormously impressive; neither the soiled and darkened surfaces nor the descent of the concourse into bland tackiness could camouflage its quality. The Port Authority has been a decent, if clueless, caretaker. Bus stations are not known for their high-end ambience; they are often placed in marginal neighborhoods and are notoriously subject to transient abuse. The biggest threat to the building is that the Port Authority totally undervalues, what it is dealing with. The terminal is a three-level structure that stretches from the George Washington Bridge to a single-story extension across Broadway. A bus turnaround connecting the two parts bridges Broadway. Buses arrive and depart on the lower and upper levels; between the two is the concourse, with its ticket booths and services. Unlike Grand Central Terminal's high-end shops and services, there are no gourmet takeout stores or fancy restaurants for commuters on the run; the most conspicuous tenants are a dentist, a credit union, a video store and an off-track betting facility, which occupies the most space on the concourse and exudes an air of abandoned hope. These uniformly dismal enterprises are housed in a zigzag of commercial construction on one side, paralleled by a zigzag of ticket booths on the other side, which may or may not be meant to echo the zigzag bus berths outside at street level. The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects reports in its journal Oculus that $14 million has been spent by the Port Authority over the past five years. The dominant design factor seems to be the overwhelming need for vigilant maintenance. The place was spotlessly clean when I visited, and the restroom--that public barometer of quality of life--immaculate and functioning give or take a few broken hand dryers, was a clear demonstration of the problems faced and solved. Everything visible or usable--toilets, sinks, even mirrors--was of solidly wall-hung stainless steel. On that day, at least, the escalators were working. Beyond a vandal-proof minimalism (and don't think trendy asceticism) the aesthetic goes casually downhill to a humdrum mix of bad signage and the unconsciously comic touch of a bronze bust of George Washington, a gift from the sculptor's son, shunted off into a neutral corner. Another bust, of O.H. Amman, the distinguished engineer of the George Washington Bridge, stands with its back to the entrance against a large and lifeless photograph of the bridge; it is a measure of the level of design sensibility that the real bridge is available by looking the other way. There is no sign of Nervi, although I understand his name appears on a plaque outside as consulting engineer, after the Port Authority's chief engineer, John M. Kyle. I don't grudge Mr. Kyle his conspicuous position; he was the man with the vision to hire Nervi. Nothing suggests the drama at the top of the escalator that leads to the local commuter bus lines. The angled butterfly trusses, open for ventilation, frame an exhilarating view of the bridge. Huge central columns receive the weight of the trusses, tapering to a dancer's lightness at the floor. Small, curved-roof glass kiosks along the platforms provide attractive and appropriate protection. The narrow, striated pattern of Nervi's concrete aggregate is visible; this is a powerfully handsome place, soot notwithstanding. There are on-again off-again proposals to maximize the land use; the idea of unused air rights is anathema to any self-respecting real-estate department, and the Port Authority is no stranger to development. One proposal would have built a cinema multiplex on top of the low Broadway structure. That has not materialized, but the possibilities are apparently being held open. The argument is made that because construction over the Broadway section would not touch the main building, Nervi's design would not be compromised. That is ridiculous, of course; the two parts are continuous, and effectively one thing, and any addition will alter the perception and integrity of the whole. This does not mean that every option is foreclosed. But a large and sensitive talent would be required, something that seems to come sporadically to the Port Authority, like every 40 years. In conventional or commercial hands, anything at all would be a disaster. Architecture is a mirror of its own moment, and some will prize this building for the hallmarks of Italian design of the '60s--those retro butterfly shapes and touches of aquamarine, and the fine Italian mosaic of the underside of the butterfly canopy that is clearly, and sadly, deteriorating. But unlike the nostalgic and lovable kitsch being championed by those who are unable or unwilling to make distinctions between what is important and what is not, Nervi's Port Authority bus terminal is a work of the first rank that demonstrates the art and science of reinforced concrete construction at its 20th-century highpoint, in the hands of one of its greatest masters. It is inconceivable that this building--in fact, any Nervi building--should not be a designated landmark. Under New York City law, it has already been eligible for a decade. It is time to look uptown. Ms. Huxtable, the Journal's architecture critic, last wrote on Louis Kahn. www.opinionjournal.com http://www.panynj.gov/tbt/aboutGWBBS.htm http://www.panynj.gov/tbt/gwbmain.HTM ---------------------------- An Overlooked Modernist Masterpiece Pier Luigi Nervi's bus terminal at the George Washington Bridge Published in Blueprint, November 2000 Is intercity bus travel so declasse that it's hard for New Yorkers to take a bus terminal seriously? That's the only explanation for the indifference to the poured concrete masterpiece by Pier Luigi Nervi that spans Broadway at the Manhattan approach to the George Washington Bridge. The building -- a station and attached parking lot, one of Nervi's few completed projects outside Italy -- is a superb example of the poetry he wrought from ferro-concrete, exploring, as he put it, "the mysterious affinity between physical laws and the human senses." Now that affinity is threatened by a planned multiplex cinema, a 50,000 square foot building (not yet designed), to be constructed over the parking lot portion of the Nervi building. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, the quasi-public organization that owns the terminal, hopes to move ahead with the plans after a structural survey is completed early next year. It is the latest example of New York treating a significant building as a plinth for another, more profitable structure -- the same Port Authority is planning a skyscraper over its other terminal, near Times Square. The Nervi building, completed in 1962, begins with a horizontal platform, raised about 30 feet over the street on angled concrete columns. Above the western half of the platform, a second series of columns support 14 triangular projections, bug-eyed clerestories that explore the otherwise neglected middle ground between Corbu and Gaudi. Striking from the outside (approached, as they usually are, from a drab section of Upper Broadway), they are nothing short of thrilling from the inside, where their concrete louvers funnel light to the waiting areas below with a mixture of precision and delight. The other half of the platform -- a parking lot -- has nothing on it but cars, and that's where the theater will be built. But the Port Authority, which stands to make millions, hasn't said how the new building will be massed. Even if it the cinema never touches Nervi's skylights, it will obscure them from some directions and compete with them from others. Like the Gwathmey-Siegel addition to Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim Museum, overhanging and threatening to overshadow Wright's rotunda, the cineplex will be a looming omnipresence. Anything that touches -- or diminishes the effect of -- Nervi's geometry should be off the table. The building was inspired by the George Washington Bridge -- which Le Corbusier called "the most beautiful bridge in the world." Nervi's structure makes clear references to the bridge's criss-cross trusses, rethinking one idiom -- call it "erector set deco" -- in another. As in his better-known Palazzo dello Sport in Rome, Nervi (1891-1979) revels in structural predetermination -- the tracery of his vaults is as inevitable as the ribs of a wood canoe -- and in the plasticity of ferro-concrete (his movable forms were made of the same material as the finished building). The brain behind these eyes is both calculating and playful. News of the planned cineplex has sent at least one architecture writer -- this one -- scurrying to see the condition of the terminal, which he hadn't visited in years. (It's common for owners to allow non-landmarked masterpieces to deteriorate to the point where no one cares what happens to them -- neglect becoming an excuse for more neglect.) In this case, while the building is far from pristine, the majesty of Nervi's creation is undiminished. The columns supporting the terminal roof are surprisingly moving (their tapering forms and striated surface suggest sequoias, yet without the slightest hint of kitsch). Above, concrete is rendered nearly weightless. The building is on a par with Saarinen's TWA terminal at Kennedy Airport, another reinforced concrete masterpiece that seems to leave the ground. But unlike Saarinen's building, which has achieved iconic status, Nervi's is little known. It has something to do with location, but a lot to do with the fact that boarding a bus to New Jersey (rather than, say, a plane to Paris) is something most New Yorkers prefer to do with eyes wide shut. www.fredbernstein.com ------------------------- Second Look: George Washington Bridge Bus Station / Pier Luigi Nervi, 1963 One of Nervi's few completed projects outside Italy is a superb example of the poetry he wrought from ferro-concrete. by Fred A. Bernstein November 2, 2004 (Photo courtesy of The Port Authority of NY & NJ - Mara Herbert - Photographer) Editor’s note: Second Look is a new series based on Fred Bernstein’s regular column in Oculus, the quarterly magazine of the AIA New York Chapter. It is reprinted here with permission. Is intercity bus travel so déclassé that Americans can't take a bus terminal seriously? How else to explain their indifference to the poured concrete masterpiece by Pier Luigi Nervi (1891-1979) that spans Broadway at the Manhattan approach to the George Washington Bridge? The structure – a station and attached parking lot, one of Nervi's few completed projects outside Italy – is a superb example of the poetry he wrought from ferro-concrete, exploring, as he put it, "the mysterious affinity between physical laws and the human senses." In 1999, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which owns the building, announced plans to build a 50,000-square-foot multiplex cinema over the parking lot. It was to be just one more example of an architecturally significant Manhattan building becoming a plinth for a more profitable structure. That, of course, was before September 11th; the plan is now on hold. Which is good news for fans of the building. The Nervi building is essentially a horizontal platform, raised about 30 feet over the street on angled concrete columns. From the western half of the platform (which is linked by bus lanes to the George Washington Bridge), a second series of columns supports 14 triangular projections – bug-eyed clerestories that explore the otherwise neglected middle ground between Corbu and Gaudi. Striking from the outside (approached, as they usually are, from a drab section of Upper Broadway), they are nothing short of thrilling from the inside, where their concrete louvers funnel light to the waiting areas below with a mixture of precision and insouciance – as if painted by Picasso from a sketch by Escher. The building was inspired by the Hudson River span; Nervi's structure makes explicit references to the bridge's criss-cross trusses, rethinking one idiom – call it "erector set deco" – in another. From above, the roof resembles one of the bridge's towers, pushed and pulled like taffy. As in his better-known Palazzo dello Sport in Rome, Nervi revels in structural predetermination – the tracery of his vaults is as inevitable as the ribs of a wood canoe – and in the plasticity of ferro-concrete (his movable forms were made of the same material as the finished building). The Port Authority (which attributes the building to "John M. Kyle, chief engineer, and Pier Luigi Nervi, consulting engineer" on a plaque in front) has, of course, tinkered with the building over the years. Recent changes to the retail/ticketing concourse (below the bus platform) include materials that would have been an anathema to Nervi. A Port Authority spokesman said the PA has spent $14 million on capital improvements to the terminal since 1999, and that it “remains open to development opportunities at the site.” For now, the building retains its power to inspire. The columns supporting the terminal roof are triumphant – their tapering forms and striated surface suggest sequoias, yet without the slightest hint of kitsch. Above, concrete is rendered nearly weightless. The building is on par with Saarinen's TWA terminal at Kennedy Airport, another reinforced concrete masterpiece that seems ready to leave the ground. But unlike Saarinen's building, which has achieved iconic status, Nervi's is under-appreciated. It has something to do with location, but a lot to do with the fact that taking a bus to New Jersey (rather than, say, a plane to Paris) is something most New Yorkers prefer to do with eyes wide shut. Fred Bernstein, an Oculus contributing editor, studied architecture at Princeton University, and has written about design for more than 15 years. He also contributes to the New York Times, Metropolitan Home, and Blueprint. © 2004 ArchNewsNow.com |

||||