|

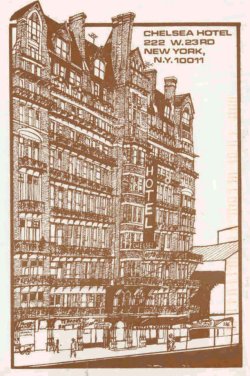

New York Architecture Images-Chelsea Chelsea Hotel Landmark |

|

architect |

Hubert, Pirsson and Co. |

|

location |

222 West 23rd Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues |

|

date |

1885 |

|

style |

Queen Anne |

|

construction |

brick |

|

type |

Apartment Building |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

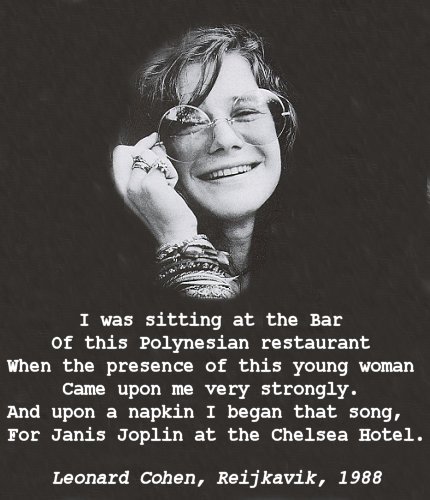

"A building, 12-story

brick, with brownstone trimmings, flat for 40 families, 175 x 86,

mansard, brick, and news patent roof, cost $300,000; owner George M.

Smith" Thus was the Hotel Chelsea, New York's first co-operative apartment complex, introduced into the city's fierce rental food chain. An excerpt from the March 29th, 1884 Record and Guide betrays the optimism of the experiment's earliest participants: "The owners of the various apartments do not think that running expenses will cost them anything, as the stores on the ground floor & the two upper stories are retained for tenants, so as to bring in an income." In addition to the points enumerated in the Real Estate Record and Guide, the building included wrought-iron balconies, apartments of one to seven rooms (built to the purchaser's specifications), high ceilings, fire and sound-proof walls, wood-burning fireplaces, and private penthouses. A unique iron staircase, constructed with a wrought-iron balustrade and mahogany banister, ran (and still runs) from the lobby to the twelfth floor. At the time of the Chelsea's inception, 23rd street served as a fleeting prototype of what would later become the quintessential thoroughfare of American theater, Broadway. Like the Bowery and 14th Street before it, 23rd Street's golden age as a theater strip would pass, but in the late 19th Century the Chelsea was in the center, with the Opera House Palace and Pike's Opera House (24th Street and 8th Avenue) down the block and Proctor's Theater ("continuous daily vaudeville") opening across 23rd Street. It was not until January of 1893 that this began to change, with the establishment of The Empire--Broadway's first proper theater--near 40th Street uptown. As New York historian Lloyd Morris has noted, "nobody realized that the opening of the Empire marked the beginning of a new theatrical era...yet it ushered in the Twentieth Century." The relocation took several years, but its process ineluctably altered the social landscape of the city. Stripped of its patina of glamour, 23rd Street became a playground for real estate developers and the forces of industrialized commerce. And so the Chelsea, once and impervious stronghold of Opulence, also succumbed to the uglier forces of the market. The financial panics of 1893 and 1903, combined with the rising costs of urban life, bankrupted the Chelsea co-operative and forced the relocation of the original tenants. By 1905, the Chelsea had been sold and reorganized as a hotel. Thus ended one grand experiment and began another, as the Chelsea Hotel began its life as a home to writers, artists, and urban transients of every variety. Down the street from the Grand Opera House was the Chelsea Hotel, another landmark of Victorian New York, which Abbott photographed the same day. Built in 1884 when 23rd Street was the center of fashionable New York, the Chelsea Hotel was architecturally conservative--its 12-story brick walls are load-bearing--and lavishly decorated. By the 1930s, it had been the home of several illustrious writers, including O. Henry, Thomas Wolfe, and Edgar Lee Masters, who appreciated its shabby elegance. Abbott may have been attracted to the Chelsea's elaborate iron balconies, an architectural feature that often caught her attention. In 1966, the Chelsea was granted landmark status, and except for a three-story-high streamlined neon sign that replaced the small sign in Abbott's photograph, the facade remains unchanged. The hotel, which was memorialized in Andy Warhol's 1966 film, Chelsea Girls, has continued to attract writers and artists. Only thanks to the imigration of artists, creative and critical spirits to the Village around the turn of the century, its charm could have been preserved. In the fifties, the Village became attractive for the beatnicks. In the sixties, the hippies came. In the seventies and eightees, it was the Rock'n'Rollers and everybody who wanted to be hip who made Greenwich Village and neighboring Chelsea symbols of the New York way of life. One of the particular spots is the Chelsea Hotel, meanwhile under national protection. This place is talking more about popular culture and its artists than any other spot in the Village. The Chelsea was famous even back at a time when Mark Twain was living in one of its rooms. Thomas Wolfe and Arthur Miller have been living and writing there. Miller, who stayed six years at the Chelsea described the famous artist's hotel like this: This hotel does not belong to America. There are no vacuum cleaners, no rules and shame...it's the high spot of the surreal. Cautiously, I lifted my feet to move across bloodstained winos passing out on the sidewalks--and I was happy. I witnessed how a new time, the sixties, stumbled into the Chelsea with young, bloodshot eyes. Until 1884, the Chelsea Hotel was the highest building in New York City. Today it is burried somewhere in the suburbia of Manhattan. The glamor of ancient time has been nagged away by the destruction done by the years. Only the main entrance with its memorial plates is reminding us of the great past of the hotel. The lobby is resembling an art gallery consisting of objects that sometimes were kept by the hotel management in lieu of payment for a rent long overdue. The reception desk looks like straight out of an old black & white Hollywood movie. Both lifts seem to move in slow motion up and down the ten-story building. Sometimes, the inside of the hotel looks like a barracs. But holes in the floors, sqeeking waterpipes or breathing heatpipes only add to the ambiente of the hotel. Nonchalance is being cultivated in this place. Luxury is unwanted. Usefulness, atmosphere and non-conformism are dominating. Pompousness is looked down upon, nonetheless there is tidyness all over the place. In the last five years, a lot of money has been spend upon the restauration of the victorian-gothic building with its many oriels. Even today, only 100 of the Chelsea's 400 'units' are available to 'normal' New York visitors, the rest of them is occupied by permanent residents. The most beautiful of all (# 600) is a luxury suite which has a marble floor and a bronze fireplace and is currently rented to the gay couple writing love stories under the moniker "Judith Gould". If you want to stay at the Chelsea, you'd be better adviced to book at least two months ahead, even if it's only a ordinary room. You rather pay for the famousness of the hotel than for the rooms themselves. You can get a room facing the street at about $ 140 and the Chelsea is highly recommended for people who love something special. Every room at the Chelsea tells its own story. In # 205, welsh poet Dylan Thomas, who reputedly inspired young Zimmerman to change his name to Bob Dylan, fell into a fatal coma after having 18 whiskies in a row. # 100 was once occupied by Sid Vicious, bass player with The Sex Pistols, and his girlfriend Nancy Spungeon. On the morning of October 11, 1978 Spungeon was found in the bathroom, stabbed to death. Viscious, arrested under suspicion of murder, died shortly thereafter of a heroin overdose. Jimi Hendrix lived, loved and experimented here, with drugs and other things. Janis Joplin did not only have a love affair with Southern Comfort but also had a short liaison with Leonard Cohen. The canadian rock poet, too, loved the hotel: It's one of those hotels that have everything that I love so well about hotels. I love hotels to which, at four a.m., you can bring along a midget, a bear and four ladies, drag them to your room and no one cares about it at all. His song Chelsea Hotel is not only a remembrance of past loves with the likes of Janis Joplin or Nico, it's also a declaration of love towards the hotel: I remember you well in the Chelsea Hotel/ You were taking so brave and so free/ Giving me head on the unmade bed/ While the limousines wait in the street/ Those were the reasons and that was New York/ I was running for the money and the flesh/ That was called love for the workers in song/ Probably still is for those of us left. The list of Big Names of literature, music or the arts scene who stayed at the Chelsea is seemingly bottomless: Jane Fonda, Jackson Pollock, Brendan Behan, Sarah Bernhardt to name but a few. They all encountered tragedies and comedies. They wrote short stories, movie scripts and novels and painted their pictures. They completed their movies within their heads, long before the actual shooting took place. Some of them had fatal endings... For many, the Chelsea was a hideout or regular adress for many years, remembers Stanley Bard, who's been the hotel manager for almost 40 years now. Some of them lived here over decades. It was only recently that punk-icon Patti Smith moved out. Stanley Bard appears to be friendly but keeps distance, on the other hand he's happy about reminicing every once in a while and he points out the bookcase in his office. I'm collecting every book that has been written in my hotel, he says taking out Thomas Wolfe's novel You Can't Go Home. Many things have happened here, he continues. Jim Morrison, Hendrix and Janis Joplin were having their drug parties here. Today, there's a 'No Smoking' sign in the hotel lobby. For many years, Bob Dylan used to live in suite # 2011, # 411 was Janis Joplin's suite. Over the years, Leonard Cohen has lived in many rooms. I like to think of him, back then. He was one of the very few calm ones in these tumultous times. But perhaps his restlessness was better hidden than that of the others. Most of his time in New York in the sixties he was living at # 424. Long after this, Jon Bon Jovi wrote the song and shot his video for 'Midnight At Chelsea" in suite # 515. But Bard refuses to talk about the mysterious Viscious/Spungeon murder case. That's a different story, he says but he's proud of Andy Warhol's love for the hotel. In the 60s, Warhol and Nico have done a movie, Chelsea Girl, at the hotel. All in all it has been a turbulent time back then, Stanley Bard resumes and wistfully finishes, I don't want to have missed any moment in the life of the Chelsea Hotel. There's hardly been an artist who has lived in the Chelsea that was not in some way captured by its flair, says Patti Smith. Of course, Leonard Cohen is amongst them and with his song Chelsea Hotel No.2 he not only remembers his former lover Janis Joplin but also puts up a monument to his former hunting trails. Nonetheless, the song has not been written at the Chelsea. I wrote this for an American singer who died a while ago. She used to stay at the Chelsea, too. I began it at a bar in a Polynesian restaurant in Miami in 1971 and finished it in Asmara, Ethiopia just before the throne was overturned. Ron Cornelius helped me with a chord change in an ealier version, Cohen remarks in the liner notes 'Some Notes On The Songs' of his 1975 Greatest Hits compilation. Cohen recorded the song in the studio as late as 1974 at the sessions for his album New Skin For The Old Ceremony but premiered the song live on March 23, 1972 at the third show of his London, Royal Albert Hall residency. Chelsea Hotel No.2, yes, but is there a Chelsea Hotel No.1 ? The answer is No, at least where Cohen's 'official' records are concerned. But, like Bob Dylan, who is varying his set list at every show to keep in fans constantly on their toes, Cohen, too, not seldomly presents radically different versions of his songs, changing lines or adding whole verses. The following version, differing from the officially released one, is commonly known as Chelsea Hotel No.1 and is featured in Tony Palmer's 1972 tour-movie Bird On A Wire. Cohen also performed this version at his show in Frankfurt on April 6, 1972. |

|

YVES KLEINTHE CHELSEA HOTEL MANIFESTO |

|