|

New York

Architecture Images-Chelsea Hugh O’Neill Dry Goods Store |

|

architect |

Mortimer Merritt |

|

location |

655-671 Sixth Avenue. |

|

date |

1876 |

|

style |

Italianate |

|

construction |

Cast Iron Facade |

|

type |

Shop |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

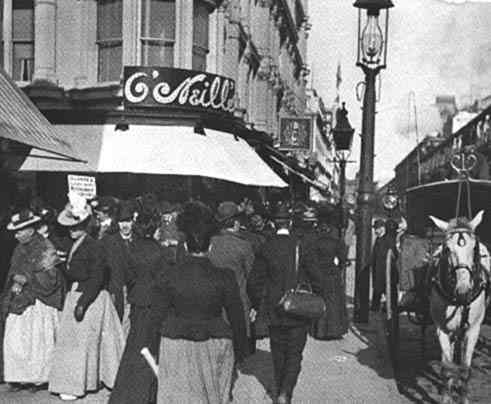

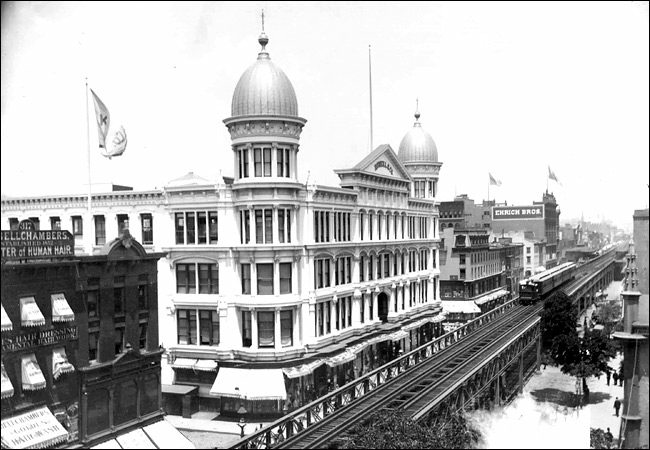

| Its Stately

Domes, Long Vanished, Are to Reappear

By CHRISTOPHER GRAY The Hugh O'Neill department store in 1890 with its pair of huge and fanciful beehive domes towering over the Sixth Avenue el. The domeless building today. HUGH O'NEILL'S giant store, built in 1887 on the east side of Sixth Avenue between 20th and 21st Streets, was the first full-blockfront building on a strip of popular department stores below 23rd Street. Its fanciful domes are long gone, but now a developer is converting the building to condominiums and plans to put them back — and he has received permission from the Landmarks Preservation Commission to enlarge the cast-iron structure. Born in Belfast in 1844, O'Neill arrived in New York as a child and began work at age 16. Just after the Civil War, he established a dry-goods store on Broadway just north of Union Square, a section that began attracting New York's elite stores as they began migrating up from the principal shopping district, Broadway below 14th. The Broadway section — with Tiffany and, later, Brooks Brothers, Gorham silver and other companies — evolved into a very exclusive area, with lower priced stores locating west on 14th Street toward Sixth Avenue. So in 1870, O'Neill decided to pursue the middle of the market and moved his operation to Sixth Avenue and 20th Street. It was a fortuitous move, as the new elevated train system began operating on Sixth in the same decade. A telling advertisement for O'Neill's store appeared in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper in 1871: "50 doz. French chip hats, just received, $3. Sold on Broadway at $6. Just received 500 cartons of French flowers, finest imported. 50 percent below Broadway prices." O'Neill had taken over several modest buildings, and in 1880, The Real Estate Record and Guide noted that instead of "the ordinary red, he has given his store a coating of yellow with black lines and brown trimmings, which is certainly very attractive and striking." The same article noted that "an apartment house of yellow would, we think, be a pleasing novelty and will prove attractive." Six months later, the architect Henry Hardenbergh filed plans for the Dakota apartment house at 72nd Street and Central Park West, and its buff-yellow brick facade was an unusual departure. In 1887, O'Neill built his blocklong store, on a stretch of Sixth that soon became a thoroughfare of giant emporia. His four-story iron front, deeply modeled, ran from 20th to 21st Streets, and The New York Times noted that "the dingy yellow, which for years seemed to be the ruling color for large places on Sixth Avenue, has disappeared, and in its place is dazzling white surface." The Times called the new building "tasteful and handsome." There were — and still are — few full-blockfront cast iron buildings in New York, and the O'Neill store had something unique: a pair of huge beehive domes at each end, 100 feet high, set on top of one-story circular rooms. Early photographs show the domes with some sort of ball or finial on top, and the roof looks like metal of some sort, perhaps gold-painted galvanized iron. Even with the elevated tracks obscuring much of Sixth Avenue, it was hard to miss the huge new building, and impossible to avoid the great domes. The building's architect, Mortimer Merritt, also put raised letters with the founder's name in a triangular pediment in the center of the building. THE first floor had silk, laces, ribbon, perfume, feathers and other items; the second floor, ladies' and children's clothes; the third, rugs and upholstery; the fourth, workshops and stock rooms. The millinery department, on the second floor at the 21st street corner, was a showpiece, with gilded columns. The ceiling and walls were finished in Japanese paper, and there was a cornice of ebony latticework with colored glass. In the corner, a banquette ran around the circular window — the nook was partly secluded by hangings of silk tapestry. The Times reported that a popular item was the "Princess Louise," "an imported wrap of Sicilian silk embroidered with cut jet beads and a fish-net sleeve." Another item was "a London walking jacket" with turned seams — "the shade in greatest demand, because it is regarded as most fashionable, is the coachman's cream color," the account said. Such goods were attractive, in some cases too attractive. In 1888, Julia Hershey of Philadelphia was detained by a store clerk for shoplifting an umbrella. The clerk said he had caught up with her outside, but she said that he was near-sighted and that she was just inside the door, inspecting the umbrella in better light. It is not clear how the case turned out. By the early 1890's, O'Neill employed 2,500 people, and in 1895 he called back Merritt to add a fifth floor, and rebuild (or perhaps reinstall) the domed turrets, with the circular rooms below them. From the street the addition appears indistinguishable from the original building. O'Neill died in 1902, leaving $8 million, just as retailing on Sixth Avenue began a rapid decline, as some of the stores, including Macy's and B. Altman, relocated to 34th Street and even farther north. In 1906, the O'Neill store merged with Adams Dry Goods, a one-time competitor on the block to the north. But the merged company closed in 1907, as garment-manufacturing firms invaded the side streets and drove out retail patronage. By the 1920's all the giant stores had been converted to lofts and manufacturing. A 1940's photograph shows the old O'Neill store occupied by the Central Time Clock company, a machinery exchange and similar businesses. By that time, the domes had been demolished. In recent years, that stretch of Sixth Avenue, now the Avenue of Americas, has been revived, as retailers like Bed, Bath and Beyond and Barnes and Noble have moved in. The O'Neill store was given a coat of very light gray paint a few years ago, and now the developer Miki Naftali is about to begin a $5 million condominium conversion, with a two-story roof addition, all designed by the architects Cetra/Ruddy. The building is within the Ladies' Mile Historic District, and the Historic Districts Council supported the plan, saying that the renewed Hugh O'Neill building would become "a showcase for the continuing revitalization of the Ladies' Mile Historic District." That is principally because Cetra/Ruddy's designs include the restoration of the domes and the circular rooms at either end — the rooms will be connected to new penthouse apartments. Three decades ago, the big stores along Sixth Avenue from 14th to 23rd were ghostly dinosaurs from another age, occupied by light industry and warehouse operations; the section was largely empty by day, and silent at night. The prospect of new domes on the O'Neill store demonstrates the astonishing changes that have swept over New York City's older neighborhoods in less than half a lifetime. Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company

|

|

|

|

Along with B.

Altman, this cast-iron building was one of first large retail establishments

in the area, supplanting a group of Gothic Revival row houses near the

Church of the Holy Communion. The owner, Hugh O'Neill, was a highly

competitive businessman who attracted a predominantly middle-class clientele

to his store with discount offers on the newly popular sewing machines and

other items. The store was somewhat short-lived, merging with the adjacent

Adams Dry Goods Store after O'Neill's death before it closed for good in

1915.

The building's highly ordered facade is marked by Corinthian columns and pilasters and it is painted white to look like stone. A projecting central section surmounted by a rooftop pediment bearing the owner's name balances two round corner towers (formerly capped with gold domes) and breaks up the monotony of the regular facade. The architects were careful to provide large, wide ground-floor shop windows and a distinctive second-floor facade intended to be seen from the 'El.' |