|

New York Architecture Images-Chelsea Starret-Lehigh Building Landmark |

||||

|

architect |

Russell G. Cory, Walter M. Cory, and Yasuo Matsui | ||||

|

location |

West 26th to West 27th Streets. | ||||

|

date |

1931 | ||||

|

style |

International Style I | ||||

|

construction |

Reinforced concrete, brick. | ||||

|

type |

Warehouse/Factory | ||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

notes |

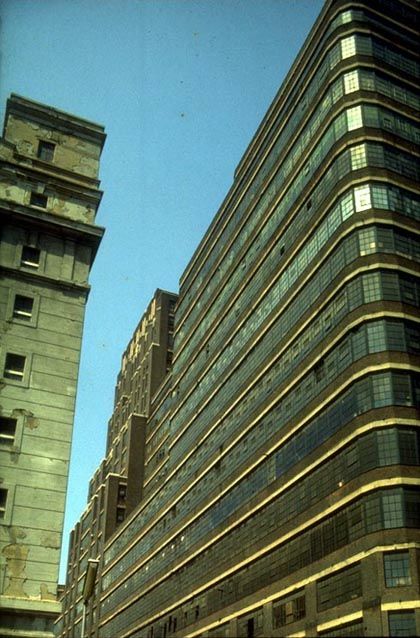

Rising above the ordinary commercial structures along the waterfront is the

Starrett-Lehigh Building, a much heralded modernist experiment in industrial

architecture. Completed in 1931, this massive factory-warehouse offered a

novel solution to freight distribution and a dramatic example of curtain

wall construction. With tracks leading directly from the piers into the

building, freight cars carried by boat from New Jersey could be moved in

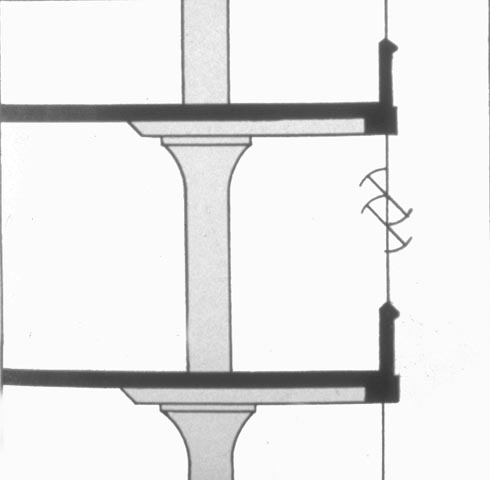

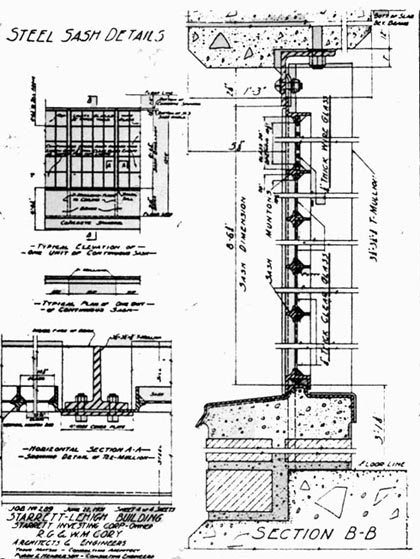

30-foot elevators to truck pits on upper floors. The horizontal bands of

windows and cantilevered concrete floors sweeping around the perimeter of a

huge city block gave New Yorkers an indigenous example of the new

International Style in architecture.

Although architecturally innovative, the Starrett-Lehigh Building never fulfilled its promise. With the Holland Tunnel (1927), Lincoln Tunnel (1937), and George Washington Bridge (1931), the Hudson River waterfront yielded its commercial activity to long-distance trucking. Inside the Starrett-Lehigh Building by C.J. Hughes The Building

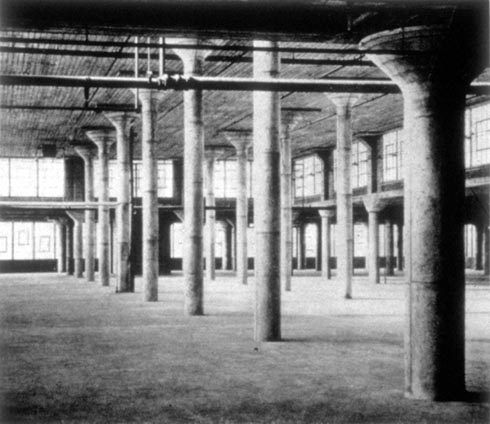

A 19-story landmarked brick-and-concrete Modernist marvel, Manhattan's Starrett-Lehigh Building rises like a multitiered wedding cake on the block bounded by West 26th and 27th streets and 10th and 11th avenues. But for some aspiring entrepreneurs, moving in has been anything but a honeymoon. The Starrett's appeal to any start-up business emphasizing the creative arts is obvious. Communal-style brainstorming is invited by cavernous office spaces supported by even rows of 35-foot golf-tee-shaped columns with trunks thick as sequoias. For fans of natural light, an unbroken line of 20-pane steel sash windows offers stunning views of the Hudson, from the Statue of Liberty to the George Washington Bridge. Designed by architects Russell G. Cory, Walter M. Cory, and Yasuo Matsui in 1931, Starrett-Lehigh was originally a busy warehouse and manufacturing center, with railroad tracks streaming right into the bottom floor. Nowadays, one's more likely to find streaming-video producers inside the 1.8-million-square-foot building, although traces of its old uses remain. Each floor is still equipped with passenger, freight, and truck elevators that allow tenants such as Martha Stewart--whose Omnimedia company will move into a 175,000-square-foot space in November--to not only drive to work, but park right next to the water cooler. In 1998, Helmsley-Spear sold the Starrett for $152 million to 601 West Associates, a group of investors who are in the process of completely gutting and redesigning the commercially zoned space for a reported $20 million. (Because it is landmarked, the building's outside is off limits.) And although much of the Starrett's interior looks raw and battle-scarred, parts of the mammoth structure are already up and running. Growing Pains As the Starrett comes back to life, the transition isn't entirely smooth. During one workday last week, well-dressed digerati hurried through a temporary lobby--the new, adjacent glass-backed lobby designed by in-house artist Maria Hellerstein was recently completed--as contractors rushed to build four new elevator shafts, scrape ceiling paint, and lay bundled T1 cables. To move to this state-of-the-art structure, tenants must fork over between $35 and $40 dollars a square foot for office space--a far cry from the $5 rate the Starrett commanded just two years ago.

So far, Screaming Media, Concrete Media, Emagine, eFinanceworks, and about six other dot-coms represent the Alley in Starrett. (Silicon Alley Reporter also keeps an office there.) Other tenants include fashion houses such as Hugo Boss, whose recently opened offices feature a state-of-the-art showroom equipped with a hologram-projection guide. Landscaped, wraparound decks are sprouting in the new, improved Starrett, but the former industrial space still contains remnants of its former self. Dangling fluorescent tubes cast a weak light on graffiti-stained hallways; piles of cinder blocks and sand fill many truck bays. Getting over there also remains a hassle--Starrett is at least two avenue blocks from the nearest subway line. Longtime tenants who can't afford the new jack-up rents say the landlords are trying to evict them unfairly. "[The landlords] claim I'm making too much noise," says ABC Die Cutting owner Irving Fox. "At what point between $6 and $40 [a foot] did I start making too much noise?" But building manager Harold Broyde says his focus is on getting the right mix of arts, media, and communication companies into Starrett--a new Con Ed generator will provide much-needed juice--even as this spring's stock downturn has him more closely scrutinizing prospective tenants. "All the Internet companies bring the stock market up and they bring it back down," Broyde says. "But this is probably the future." Battle Lines Still, the rush to build a dot-commune--where like-minded businesses may someday network under the same roof--may have already resulted in some favoritism. Urban Box Office, a vertically integrated community space located at Starrett for the past year that's staffed mainly by minorities, was kicked out in June in what it claims was a racist action. "They said they didn't like the 'quality of people' we brought to the building," says CEO and co-founder Adam Kidron. "Seeing as our kids are amazing quality, and have won numerous awards, and they've done great work, we can only assume that when he was talking about the quality of the person, it was about their race." Unlike most of the existing tenants, UBO was paying market rate for its space, $30 per square foot. The company is also relatively flush with $27 million in capital, so there was no financial incentive to kick them out, Kidron says. UBO's version of the timeline goes something like this: In July 1999, Tomar Studios legally sublet its office to UBO, and in November, 601 West handed UBO keys and gave it permission to expand into an adjacent office on Starrett's south side. This expansion occurred with the understanding that 601 West was in the process of drafting a new lease that would allow UBO to reside in the Starrett for 10 years. Two months later, 601 West served UBO with an eviction notice, charging that UBO employees were illegally smoking and gathering in the hallways. When UBO refused to leave, 601 West sent in the fire department to bust them for overcrowding, but--according to Kidron--after almost 10 fruitless inspections, "most of [the inspectors] were more interested in getting the phone numbers of the girls who work here." Kidron also claims the landlords refused to clean their hallway bathroom (as dirty as the one in Trainspotting, according to another disgruntled employee), and the elevator operators wouldn't stop on the 12th floor, where the office was located. When the eviction notice didn't work, 601 West resorted to extortion, according to Kidron. The company turned off the electricity to the office for a two-week period in May, and said it would only turn the power back on if Kidron offered them warrants for 2 percent of the company (and even then, UBO would only be allowed to stay in the Starrett until the end of the year). Kidron said no. Finally, Kidron agreed to move out if 601 West would give them back electricity immediately. "[601 West head Harry Skydell] was basically God in that building," Kidron says about the stand he took. "And you can't let God become the devil." Skydell himself didn't return calls seeking comment for this article, but as far as building manager Broyde is concerned, there's no bad blood between 601 West and UBO. "I happened to like the company, personally," he says, even though he insists that that UBO's original lease with the Tomar Studios was never approved. Still, there were disagreements. "They did things that were not beneficial to the building," Broyde says. "One thing is, they had meetings all over the building, and on the roof, where they weren't supposed to." Kidron scoffs at this suggestion, saying staffers once gathered on the roof for a memorial service for co-founder and former Motown Records president George Jackson--and had full permission to do so. "It shows me that if you can be so inhuman to use someone else's death as a negotiation play, you're better off not having negotiations," Kidron says. UBO is currently housed on Avenue of the Americas and West 31st Street in an 18,000-square-foot space (which is 4,000 square feet bigger than the company's Starrett space, contrary to some reports) until December, when the company will relocate to 126th Street and Amsterdam in Harlem. And even though the company is enjoying some momentum right now--four new animated UBO channels are now hitting the Internet airwaves, with live action programming scheduled for the fall--Kidron is still seething about how the Starrett treated his company. "I'm not at all happy with the chapter's being closed," Kidron says. "I wouldn't be [commenting for this article] at all, if it wasn't to warn people that this [Skydell] is a bad guy." There are many employees who share Kidron's dislike of their former landlord, but at least one UBO employee isn't so sure that 601 is entirely in the wrong. "If I were a landlord, I could certainly see 100 different reasons why I wouldn't want these people in my building, and it would [have] nothing to do with the fact that it's a largely minority-staffed company," says an employee of UBO channel IndiePlanet. "[UBO] is the most rambunctious, uncontrolled group I've ever been around in a professional setting," the source says. A look around the building shows that UBO isn't the only company unhappy with its treatment. In the past year, tenants have filed at least 12 lawsuits against the landlords, mostly arguing that they're losing money or being unfairly displaced because of the renovations. ABC Die Cutting owner Irving Fox, for one, can't afford the new jacked-up rents. Fox, who has been in the building for 16 years--long before it was a New Economy hot spot--had been paying only $6.10 a square foot, before the IT outfits swept in. "They claim I'm making too much noise," says Fox, whose manufacturing facility occupies the floor above Martha Stewart's space. "But it's like the judge said in the case: At what point between $6 and $40 did I start making too much noise?" Fox also claims 601 West is punishing him in the meantime by reducing the number of operating freight cars in the building from five to three, and the number of truck elevators from three to two. In addition, trucks now have to come through the narrow basement entrance, which means any vehicle longer than 28 feet can't get in. Someone who shares Fox's pain is Spiros (he would give only his first name), owner of the 12-year-old Starrett Restaurant on the Starrett's mezzanine floor. Spiros says 601 West is currently trying to evict him, even though he's been dealing with them in good faith--he gladly relinquished 3,000 square feet of space so 601 West could construct the towering lobby. In exchange for the space and other concessions, 601 West was supposed to lower Spiros' rent, a promise that was never fulfilled. "They play all these games," says Spiros, who wouldn't elaborate because of his ongoing lawsuit against 601 West. "We went to court to open the glass doors [leading to the restaurant], then they opened them. Now, they closed them again." Embattled Chelsea Moving & Storage owner Jerry Saidon finally raised the white flag on June 15 and moved out of the Starrett after four years. 601 West officially evicted Saidon from his 9th floor location for having installed illegal metal security gates, but Saidon claims it was really to cash in on the building's newfound popularity. Saidon was paying only $7 a foot for space that can now command at least four times that. "I'm mad more about the way they dealt with me," says Saidon, who maintains that his short-lived battle cost him $100,000 and his health. "Nobody has the guts to go after them." Saidon blames new arrivals like Martha Stewart for his eviction. Like many of those forced out, he's angry that 601 West has pushed so aggressively (and unethically) to get the right mix of content-producers, webheads, and Netizens into the Next Big Space. "If you pay someone to shoot someone else, you are still guilty. Martha Stewart watched from a hill while they shot me," Saidon says. "I don't believe this can happen in America. If this happens in another country, we send in the Marines."

|

||||