|

New York Architecture Images-Chelsea The High Line |

||||||||||||

|

architect |

New York Central | ||||||||||||

|

location |

runs from 34th and 10th to 14th and 10th. | ||||||||||||

|

date |

1930s | ||||||||||||

|

style |

Art Deco | ||||||||||||

|

construction |

steel | ||||||||||||

|

type |

Utility rail viaduct | ||||||||||||

Bridging the street here is a disused elevated

railroad that was used to transport freight along the Westside

waterfront, replacing the street-level tracks at 10th and 11th avenues

that earned those roads the nickname "Death Avenue." Built in 1929 at a

cost of $150 million (more than $2 billion in today's dollars), it

originally stretched from 35th Street to St. John's Park Terminal, now

the Holland Tunnel rotary. Partially torn down in 1960 and abandoned in

1980, it now stretches from Gansevoort almost to 34th--mostly running

mid-block, so built to avoid dominating an avenue with an elevated

platform. In its abandonment, the High Line became something of a

natural wonder, overgrown with weeds and even trees, accessible only to

those who risk trespassing on CSX Railroad property. Plans are underway

to turn it into a park, open to the public; it will be a tricky

balancing act to add safety and amenities without sacrificing the lost

ruin quality that makes it so cool.

Highline

Gallery One

Highline

Gallery One Highline Gallery Two

Highline Gallery Two

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

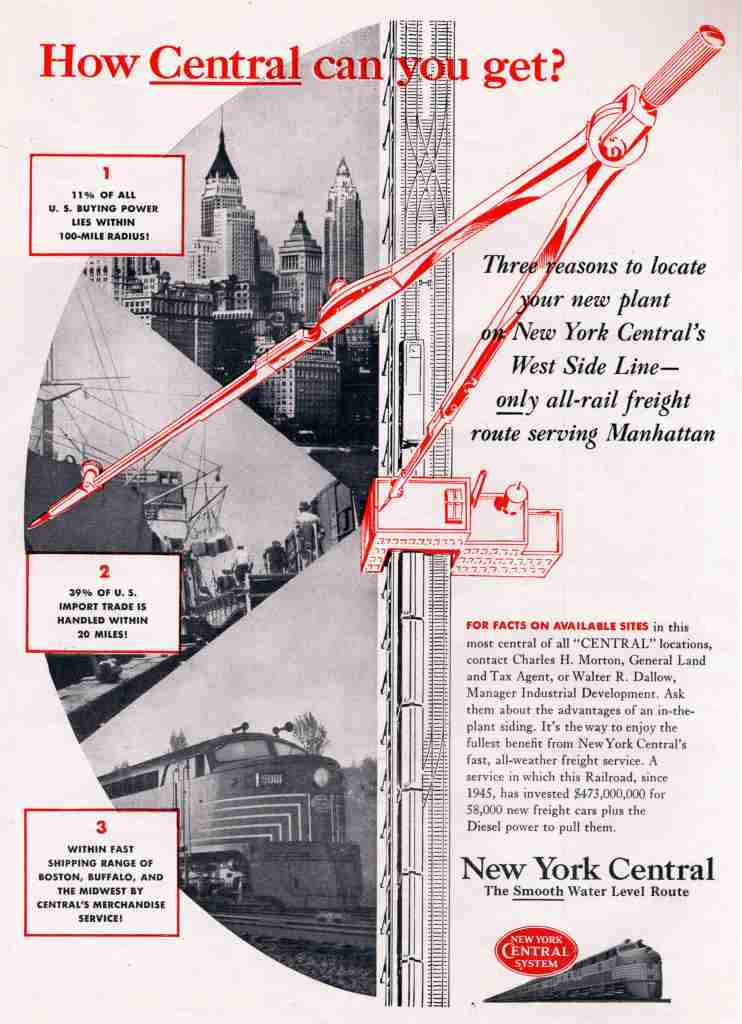

| The High Line was

built in the 1930s under an agreement between the New York Central Railroad,

New York State, and New York City, to elevate dangerous and congesting

railroad traffic above city streets. The High Line was part of the larger solution, known as the West Side Improvement Project, which was completed in 1934. The West Side Improvement stretched for 13 miles, extending from Spuyten Duyvil at its northern edge to Spring Street at the south. It eliminated 105 street crossings, added 32 acres to Riverside Park, and served as the "Life Line of New York," bringing food and merchandise into the city. The rise of trucking in the 1950s led to a drop in rail freight on the High Line, and in the 1960s, the southernmost portion, between Bank and Clarkson Streets, was torn down. The final freight train carried three carloads of frozen turkeys down the High Line in 1980. In 1993, another chunk of the viaduct, between Bank and Little West 12th Streets, was demolished. |

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Prior to its construction, Tenth Avenue was known as "Death Avenue" due to the high number of accidents caused by the mix of rail traffic, other vehicles, and pedestrians. | |||||||||||||

|

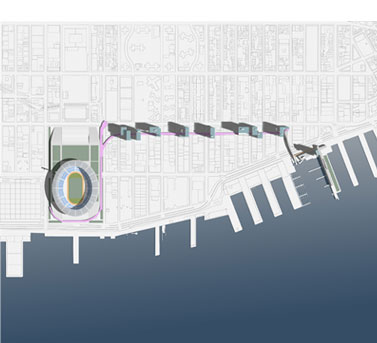

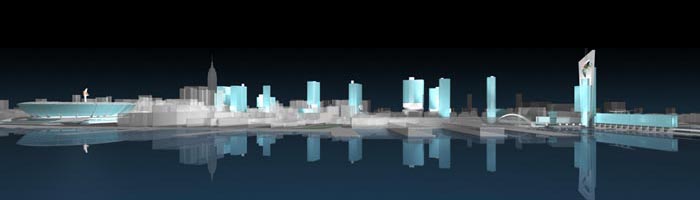

The High Line is an abandoned 1.45 mile (2.33 km) section of the former

elevated freight railroad of the West Side Line, along the lower west

side of New York City borough of Manhattan between 34th Street near the

Javits Convention Center and Gansevoort Street in the West Village. The

High Line was built in the early 1930s by the New York Central and has

been unused by freight service since 1980. It is in a state of

disrepair, although the elevated structure is basically sound. Wild

grass and plants grow along most of the route. The community-based group Friends of the High Line[1] was established by neighborhood residents Robert Hammond and Joshua David, leading to plans to turn the High Line into an elevated park or greenway, similar to the Promenade Plantée in Paris. In 2004, the New York City government committed $50 million to establish the proposed park. On June 13, 2005, the U.S. Federal Surface Transportation Board issued a certificate of interim trail use, allowing the city to remove most of the line from the national railway system. On April 10, 2006, Mayor Michael Bloomberg presided over a groundbreaking ceremony, marking the beginning of construction on the High Line project, turning it into an elevated park. The project is being undertaken by landscape firm Field Operations and architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro. Hotel developer Andre Balazs, owner of the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles, is building a 337-room hotel straddling the High Line at Little West 12th Street. As of Spring 2007, most of the old rail tracks have been removed, making way for the park.[2] If work goes as planned, the southern section of the High Line, from Gansevoort Street to 20th Street will be open to the public in Summer of 2008, creating a natural oasis in an urban city. This southern section will include five access stairways and three elevators. The park will eventually extend from Gansevoort Street north to 30th Street where the elevated tracks turn west around the Hudson Yards development project[3] to the Javits Convention Center on 34nd Street. The northernmost section, from 30th to 34th Streets, is still owned by the CSX railroad company. Museum site The Gansevoort Street terminus at the south end of the High Line was considered for a new museum by the Dia Art Foundation, but has decided against it. The Whitney Museum is now seriously considering the site as an alternative to an addition it has been planning at its uptown location.[4] In literature In Walking the High Line (ISBN 978-3882437263), photographer Joel Sternfeld documented the dilapidated conditions and the natural flora of the High Line between 2000 and 2001. The book also contains essays by Adam Gopnik and John Stilgoe. The High Line is discussed in Alan Weisman's The World Without Us (St. Martin's Press, 2007) as an example of the unstoppably resilient power of nature. |

|||||||||||||

|

High Line reuse picks up steam By Albert Amateau

At a Manhattan hearing of the federal Surface Transportation Board, which has jurisdiction over the nation’s railroads, Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff and City Planning Commissioner Amanda Burden and others testified that they foresaw the derelict rail viaduct being transformed into a green spine linking three evolving neighborhoods. The High Line is the key to the future of the Gansevoort Market, the West Chelsea gallery district between 16th and 30th Sts. and the proposed new residential and commercial rezoning of the Hudson Yards district between 30th and 42nd Sts. west of Ninth Ave., according to the testimony at the Thurs. July 24 S.T.B. hearing. Even Chelsea Property Owners, a group of property owners demanding demolition of the High Line since 1989, acknowledged that it might drop its opposition to saving the 70-year-old structure. Doug Sarini, president of Chelsea Property Owners, told the S.T.B. that the Bloomberg administration has been suggesting to owners of property under the High Line that their development rights could be transferred to other sites. “If the city and the property owners can reach an agreement, C.P.O. will withdraw its objections,” Sarini said. “But until then, we intend to press for demolition,” he added. Sarini explained later that the High Line has made it impossible for owners to develop and realize the value of their property. The transfer or sale of development rights to other sites might allow owners to realize their properties’ value, Sarini said. Vishaan Chakrabarti, head of City Planning for Manhattan, said the proposal to transfer development rights to neighboring sites would bring value to the surrounding area and allow the High Line to have light and air. Under previous administrations, the city had sided with property owners who saw the rusting steel structure just west of 10th Ave., last used for freight in 1980, as a blight on the neighborhood. Indeed, in one of its last official acts in 2001, the Giuliani administration signed an agreement joining the property owners’ move to demolish the High Line. But Friends of the High Line, a group of Chelsea residents, had begun promoting the preservation of the viaduct under the federal Rails-to-Trails program, which provides for recreational use of rails that could be restored to transportation uses in the future. Mayor Bloomberg and Commissioner Burden were quick to see the possibilities. The Friends, founded by Joshua David and Robert Hammond, found influential support in Phil Aarons, a principal in Millennium Partners, a real estate development firm, who also testified last week. The Friends have asked the S.T.B. to reconsider a 1992 decision that paved the way to demolition. Members of the S.T.B. walked the weed-covered structure a few hours before the July 24 hearing that was convened to consider the Bloomberg administration’s application last December for a certificate of interim trail use for the High Line. “Back in 1989 city officials said the High Line had to come down. What has changed in 14 years?” asked Roger Nober, S.T.B. chairperson. City Council Speaker Gifford Miller replied that there was no imaginative vision for the future until recently. “The example of the Promenade Plantée in Paris helped,” he added, referring to an unused rail viaduct converted into a park in Paris. However, he credited the Friends of the High Line with changing the way many people view the structure. “I first thought the idea was wacky, a park 18 feet above the street,” Miller said, “But when I walked on it I could see it as one of the most exciting proposals in the city.” Doctoroff said the change in the city’s position reflected the changes in the neighborhoods. “Ten years ago there were almost no galleries in West Chelsea and there was no activity to the north in the Hudson Yards for years,” Doctoroff said. “To the south, the Meat Market is rapidly changing and becoming a unique destination place,” Doctoroff added. The deputy mayor said that approval of the certificate of interim trail use was the best and perhaps the only way for the High Line to fulfill its potential. Commissioner Burden recalled touring the High Line a year ago. “It was a transformative experience,” she said. “I could see it as a unique public experience, a 22-block elevated park connecting neighborhood to neighborhood, providing a sense of place like no place else,” she said. Peter J. Shudtz, lawyer for CSX, the railroad that owns the line, said the line needs a decision soon on whether the city’s request for a certificate of interim trail use is legal. An agreement dating from 1992 limits the railroad’s liability to $7 million, but it was not signed by all the property owners. Friends of the High Line entered the case claiming that the $7 million liability cap did not cover environmental liability. Shudtz asked the S.T.B. to rule on the environmental issue. A State Supreme Court decision that demolition of the High Line requires a full uniform land-use review procedure, or ULURP, is still under appeal.Also testifying in favor of converting the High Line were representatives of U.S. Rep. Jerrold Nadler and City Councilmember Christine Quinn. John Lee Compton spoke in favor of the High Line for Community Board 4. Jo Hamilton spoke for the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, which is calling for designation of the Gansevoort Market Historic District. The Gansevoort District under consideration by the Landmarks Preservation Commission excludes three blocks from Gansevoort to 14th Sts. between the High Line and West St. because of uncertainty about the future of the rail viaduct. The Municipal Art Society, American Institute of Architects, the Society for Industrial Archeology, the New York chapters of the American Planning Association and the American Institute of Architects also urged preservation. The S.T.B. chairman called on the city, the Chelsea Property Owners and the railroads to submit written arguments in the next 30 days on the question of whether the city is legally entitled to a certificate of interim trail use. The High Line was built in the 1930's as

part of the West Side Improvement project. The project also

included the construction of the Henry Hudson Parkway and the expansion

of Riverside Park. Tracks that once ran through Riverside Park as

a surface ROW were covered over, allowing for more parkland above the

ROW. A trenched railroad cut made up the ROW from 72nd Street to

34th Street. The elevated portion of the High Line ran from 34th

Street to Clarkson Street. Before the High Line was elevated,

freight trains ran along the surface streets of 10th and 11th Avenues.

Having trains running up and down surface streets was a dangerous

undertaking, and many accidents - both vehicular and pedestrian -

resulted in each street being referred to as "Death Avenue".

Like many New York City infrastructure projects at the time, Robert

Moses played an instrumental role in the construction and development of

the High Line and the West Side Improvement project. Map provided by Harry Hassler;

original map creator unknown. It appears as if the demolition company cut the structure at where the trestle for Washington Street and Gansevoort Street once stood. A store resides below the viaduct. This area is just south of the New York

City's infamous meat market. In fact, many of the High Line's old

railroad freight traffic consisted of deliveries to various meat market

warehouses along the ROW. |

|||||||||||||

|

Elevated Visions

July 11, 2004 By JULIE V. IOVINE Proposals for the High Line THE High Line is an abandoned 1.5-mile stretch of overgrown railroad viaduct that runs from the Meatpacking district to Hell's Kitchen — and straight into the imaginations of a growing number of New Yorkers who see it as proof that, even in an urban jungle, the forces of nature are still at work. The idea to turn the old freight route, once condemned to demolition, into a public park has gained momentum over the past five years, culminating in a design competition that attracted 52 entries. On July 16 the proposals of four finalists will go on display at the Center for Architecture on LaGuardia Place near Bleecker Street. By most standards, the High Line possesses none of the qualities of a park. An elevated rail line 30 to 60 feet wide and two stories above street level, it was built in the 1930's to connect the Pennsylvania Railroad Yards and the warehouses of Greenwich Village. By 1980, most of the industries it had served were defunct, the trains were derailed, the tracks went to seed and the myth began to sprout. It was fertilized by a series of photographs taken in 2000 by Joel Sternfeld, showing off the industrial ruin as a particularly contemporary landscape — the eerie serenity of its black rails sweeping through a snowy strip of stubble in the winter, bristling waves of grass poking out between its steel trusses in the summer. Last year, the Friends of the High Line, a group of artists, writers and concerned neighbors, invited architects, designers and homegrown visionaries to submit blue-sky ideas for the track's future. It attracted 720 entries from 36 countries, including one proposal to turn the entire length of the railroad bed into a swimming pool. After that, a $15 million commitment from the City Council and a rezoning proposal helped catapult the High Line's revival from long shot to a viable scheme, and a more selective competition for a workable master plan was undertaken. The caliber of the finalists — from Steven Holl, a Manhattan architect who had previously proposed a series of bridge-shaped houses straddling the rails, to Zaha Hadid, the London-based architect who won the 2004 Pritzker Prize — reflects the seriousness of the project. Total rebuilding, however, is not part of anyone's plan. "The park of the future will be built on industrial sites like this one," said Robert Hammond, a co-founder of the Friends of the High Line. "And we want to show that a park doesn't have to be Central Park to succeed. It can be a thin linear space cutting next to buildings." The winning team will be announced in August, at which point its design will be subject to revision. The Friends of the High Line and city representatives who will be judging the competition expect contestants to give the High Line a new life and purpose while still respecting its serendipitous character as a streak of wilderness in the city. Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company ---------------- HIGH LINE: SKY'S LIMIT By TOM TOPOUSIS July 15, 2004 New Yorkers will get their first glimpse today of dramatic proposals to convert a long-unused railroad trestle on Manhattan's West Side into a spectacular park in the sky, including calls for high-flying pools, wetlands and nature trails. Four design teams have submitted their proposals in hopes of winning the prestigious job of transforming the High Line into a 1.5-mile public space that stretches from the Meatpacking District through the art galleries of Chelsea. "They've met our expectations and exceeded them," said Joshua David, a co-founder with Robert Hammond of the group Friends of the High Line, which is coordinating the project with the city's Planning Department. The Post obtained an exclusive look at the designs, which range from a modernistic overhaul of the viaduct into a series of outdoor art projects on one end of the spectrum, to rustic paths through fields of grasses and wild flowers on the other. Beginning tomorrow, the proposals will be on public display at the American Institute of Architecture's gallery at 536 La Guardia Place in Greenwich Village. A finalist will be chosen in August and a master plan for the project is expected by next spring. The High Line, once slated for demolition and now strictly off limits to the public, is on track to be fully opened by 2006, with some sections made accessible earlier as work on the viaduct goes along. The project will cost about $65 million. The design teams are: * Field Operations with Diller, Scofidio and Renfro: James Corner, founder of Field Operations, envisions a "fantastic, mixed perennial landscape" punctuated by "event spaces" that would include a clear-bottomed pool and a grandstand rising off the trestle. * Steven Holl Architects: Steven Holl calls the High Line "a suspended valley, a green strip" running through Chelsea. His plan includes a landscaped tower at the north end. "It's a piece of Zen poetry and I insist that it shouldn't be over-programmed." *TerraGram/Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates: Team leader Michael Van Valkenburgh said the design will be "a celebration of the natural phenomenon" already taking root on the train trestle and will include plantings of mustard seed and sunflowers that eliminate toxins in the soil. * Zaha Hadid Architects: Markus Dochantschi, who coordinated the team, described the High Line as a rare horizontal setting in a vertical city. "Our theme is movement and the dynamic of movement," he said of the plan that would include rotating public art shows. Copyright 2004 NYP Holdings, Inc. -------------------- High Line forum packed tighter than a subway car By Albert Amateau Over 500 people attended a forum on the future of the High Line elevated railroad at the Center for Architecture on LaGuardia Pl. last week. If the overflow crowd at the Center for Architecture’s forum on the High Line last week is any indication, future visitors to the elevated park between the Gansevoort Market and the Javits Convention Center will barely fit on the 30-ft. width of the old rail viaduct. “Since we opened last fall, this is the largest crowd we’ve had here,” said Rick Bell, executive director of the New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, referring to the 500 people who crammed into the Center at 536 LaGuardia Pl. for the July 15 presentation on the future of the High Line. Others who tried to get in could not, and were left standing outside on the sidewalk. The focus of all that attention was the four teams that submitted scenarios to convert the disused 1.3-mile railroad viaduct into an elevated park that traverses Chelsea along the west side of 10th Ave. — where more than 200 art galleries occupy old warehouse space — and the Meat Market in Greenwich Village. Team leaders used words like “magical,” “unruly” and “wild,” to describe aspects of the elevated railroad that they intend to honor and enhance but inevitably change by transforming it into a public park. And to one degree or another, all four teams are committed to providing public access to the High Line as soon as possible, even if that access is only temporary at first. Steven Holl, an architect and leader of one of the teams whose office overlooks the High Line at 31st St., recalled seeing a blue butterfly on the viaduct during a recent visit. Looking ahead to 2050 to “a suspended valley” among the tall buildings of the future, he said, “As long as we can see a butterfly, we will have achieved that balance we’re seeking.” Built by the now-defunct New York Central Railroad 70 years ago to raise street-level freight trains from the surface of 10th Ave. — where they were an impediment to traffic and a menace to pedestrians — to tracks 20 ft. overhead, the High Line has been unused for 20 years and is overgrown by the seeds of windblown grasses, weeds and trees. Friends of the High Line, organized by Chelsea residents Joshua David and Robert Hammond in 1999, began working for what was then considered the romantic folly of preserving the line that had originally served West Side factories and warehouses. But the Bloomberg administration adopted the idea and has made a public promenade on the High Line the central element in the proposed redevelopment of West Chelsea, the planned construction of the controversial New York Sports and Convention Center and the redevelopment of the Hudson Yards. “We begin with the strange, otherworldliness of the High Line and the emergent growth over time as new space is built. But as soon as it becomes a public space, it can no longer be like this,” said James Corner, landscape designer and leader of the Field Operations team. The Field Operations vision has an interaction of hard and soft surfaces, including dips into pools in some places with the path flying above the track bed in areas that are to remain untrodden. Elizabeth Diller, an architect member of the Field Operations team, suggested sections for events that could accommodate as many as 200 people. At places where the High Line goes through buildings, like the Chelsea Market, the former National Biscuit Company building between 15th and 16th Sts., there could be commercial uses to generate income to maintain the High Line. “The extraordinary thing about this project is its improbability and the constant transformation of space that will never be completed,” Corner said. Holl also paid tribute to the open-ended transformation of the High Line and the space beneath. “The High Line has been evolving for 70 years and we hope to make it a part of the city — not headed to a fixed end,” he said. The structure was built to handle freight trains and is four times stronger than it must be for a pedestrian promenade, Holl said. He envisioned the structure without its concrete skin and some steel removed to create a lattice, allowing light to penetrate to the street below. Colored lighting provided by LEDs on the underside of the viaduct would promote attendance at the art galleries that have come to dominate the West Chelsea district. Michael Van Valkenburgh, landscape designer and leader of the TerraGRAM team, invoked the name of Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of Central Park in the 19th century. “We’re bringing the High Line into the 21st century, taking its glaring limitations and making it the Central Park of this century,” Van Valkenburgh said. The High Line will be a transition between “the dog and the wolf,” he said — the dog being the built environment underneath and around the viaduct and the wolf being the wild growth on top. Van Valkenburgh’s vision includes zoned gardens with the neighbors of different stretches taking part in the creation and maintenance of the High Line flora. He also suggested stripping some of the viaduct to let people see the fundamental structure of New York City. “In time, we hope to have stairs at every intersection emerging into a miniature forest of trees,” Van Valkenburgh said, adding, “But it’s important to keep the rails visible at all times. We can’t lose the idea of a real railroad.” Zaha Hadid, winner of the 2004 Pritzker Prize for architecture and the first woman so honored, is the leader of another team that sees the High Line as “a ribbon which can expand or shrink as needed.” The Hadid team, which includes The Kitchen, a West Chelsea arts venue, as cultural advisor, sees art installations and programs as an important element of the High Line. “We hope to engage the streets as part of the effect of the High Line,” Hadid added. All the teams have consultants for dealing with any toxic residue of nearly 50 years of rail use. “CSX [the company that inherited the High Line from Conrail, which took it over when New York Central collapsed] will be very nervous if we keep talking about toxicity, but in fact, there’s very little there,” said Van Valkenburgh. The federal Surface Transportation Board must approve the application by the city and the Friends of the High Line to include the viaduct in the federal rail-banking system’s Rails-to-Trails program. That approval is likely since opposition by Chelsea Property Owners, whose property is under the viaduct, has evaporated after the city’s promise to allow them to sell their development rights to developers of properties elsewhere in a proposed West Chelsea special district. During the past 30 years, residential developers of property under the High Line between the St. John’s Building — a former rail terminal for the High Line — north of Canal St. and Gansevoort St. were able to convince the federal government to approve demolition of the southern stretch of the viaduct. Friends of the High Line and the city hope to select a development team from among the four submissions by September. The winning team will develop a master plan in a process that will include frequent public meetings, and construction is to being early in 2006. “We don’t know what the cost might be until we have a master plan, but we’re estimating it to be between $65 million and $100 million,” Hammond said. The city has so far committed $16 million and Congressmember Jerrold Nadler has secured $5 million in federal funds. “We hope Senators Schumer and Clinton will secure more federal funds and we hope to raise private funds,” Hammond said, adding, “We think we’ll have enough money to start construction.” Senator Clinton is a strong supporter of the project. “The High Line project represents the extraordinary things that can be accomplished when a community organizes and decides it wants to move an idea forward,” Clinton recently said in a statement to The Villager. “That’s why I’ve been an ardent supporter of this project, because I believe it will help create a unique and scenic landmark on Manhattan’s West Side that will be treasured for generations.” The Villager, Volume 74, Number 12 | July 21 - 27, 2004 --------------------- Remaking Tracks Four plans would transform the High Line, an overgrown vestige of the city's industrial past, into a vibrant swath of its future BY JUSTIN DAVIDSON STAFF WRITER July 29, 2004 A strip of forgotten wilderness runs down the West Side of Manhattan like a weedy seam. The High Line, an abandoned elevated railway that snakes its way from West 34th Street to the Gansevoort Meat Market, is a rusting relic of the industrial age. Built in the 1930s to carry freight in and out Manhattan's manufacturing district, it was eventually condemned to obsolescence by the combined forces of gentrification and trucking. It has become a pastoral avenue that nobody sees. In the 24 years since the last load of frozen turkeys was delivered by train to a Greenwich Village warehouse, weeds and wildflowers have sprung from its gravel beds, obscuring the tracks and suggesting a possible future as a verdant walkway above the streets. Some local businesses see it as an obsolete eyesore, shutting light out from the sidewalks and depressing property values. But the Bloomberg administration and a small army of celebrities have sided with Friends of the High Line, an organization that wants to transform the dilapidated structure into a destination. Last year, that nonprofit group solicited ideas about how to accomplish that. It received 720 suggestions, from the minimal (leave the weeds) to the preposterously extravagant (a mile-and-a-half-long swimming pool). Now the organization is conducting a more realistic competition for a master plan and has narrowed the field to four teams of architects. The romance of the project has attracted major talent. Zaha Hadid, this year's Pritzker Prize winner, leads one team. Another includes Diller, Scofidio + Renfro, which has been hired to refurbish Lincoln Center. A third is captained by the esteemed architect Steven Holl and the fourth, called Terragram, is led by the landscape architect and Harvard University professor Michael Van Valkenburgh. So far the process has produced only general design approaches. An exhibit of the four proposals is on view at the Center for Architecture until Aug. 14. Whichever team gets the job in the fall will then plunge into a new round of studies, debates and brainstorming sessions, emerging with a full-fledged master plan next year. In the meantime, New Yorkers can look forward to a new kind of urban park, a distinctly local equivalent to the European passeggiata. The pedestrian boulevard will thread its placid way through a neighborhood's shuddering changes. In the past 20 years, the westernmost slice of Chelsea, between 10th Avenue and the Hudson River, has metamorphosed from a gritty industrial district to an area sprinkled with art galleries and chichi restaurants. The Bloomberg administration is trying to shape the next phase of that transformation by applying a nudge here and a brake there. Last fall, the city's Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the Gansevoort Meat Market area as a historic district, protecting its cobbled streets and its warehouses, with their corrugated-metal awnings, from demolition. At the same time, the city planning commission unveiled a proposed rezoning of West Chelsea, which would allow a flock of new apartment buildings. Meanwhile, the city is negotiating the tension between change and preservation by cheering on the renovation of the High Line. Its future as a park is far from a sure thing. Money must be raised - somewhere between $60 million and $100 million - and the federal government must be persuaded to fold the project into the rails-to-trails program through which disused railroad tracks can be converted into parks and bicycle paths until they are needed as train routes again (in most cases, never). Each of the four finalist proposals for the High Line would create an immeasurable improvement in the life of Manhattan. The tragic mistake would be to demolish the High Line or let it continue to decay. Field Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro Diller, Scofidio + Renfro teamed up with James Corner and his landscape firm, Field Operations, to create the most provocative and vivid of the four proposals: an undulating platform that would preserve some of the railway's current sense of wilderness. For now, the tracks run through an uncultivated grassland. The proposal would pave the structure with long concrete planks, sometimes tightly fitted, sometimes separated by gaps overflowing with vegetation. Meadow would shade into strips of brush and woodland thicket, fading, perhaps, into patches of artificial marsh. Like a combination of boardwalk and dune, concrete ramps would arc above the trees, providing lofty views, or swoop down between the steel girders, cocooning pedestrians in greenery and allowing them to forget for a moment the city all around. The up-and-down intentionally slows the typical New York City quick-march to a contemplative stroll. Those in a hurry need only click down the stairs to the churning sidewalks. In all the proposals, the High Line becomes a place of spectacle, too. This team's more fanciful renderings envision high-flying acrobatic demonstrations and a stretch of elevated beach, complete with swimming hole. But Field Operations also foresees havens for more easily conceivable activities: outdoor movies, people-watching and light shows illuminating the line's several passageways through existing buildings. At the southern end, sculpted nature gives way to raw industrial artifact. Naked steel beams extend over a long, grand staircase by the Gansevoort Meat Market, where a glass wall turns butchering into a spectator sport. Perched above it all is a cantilevered glass gallery like the top of a "T," a transparent box whose principal purpose is to let people see and be seen. Zaha Hadid The core challenge of the High Line will be to make attractive the idea of lifting street life into the air. Hadid, the celebrated Iraqi-born architect based in London, draws pedestrians through vertical space like salmon upriver, in an instinctual flow of desire. In her Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati, for instance, she merges floor, wall and walkway to give the museum the feeling of a continuous, ribboning structure. Her proposal for a High Line master plan has some similarities with that of Field Operations: zones of vegetation that bleed into each other without formal borders, and a surface that rolls above and below the horizontal plane defined by the railway girders. But Hadid envisions a more liquid structure, an architectural stream fed by the tributaries of building, park and street. At 18th Street, people would enter her version of the High Line by ambling up a looping, meadowed, handicapped-accessible ramp that doubles as the roof of a tubular building. The hurried and able-bodied could climb a standard set of stairs, but the gestural drama of the landscape emphasizes the ramp. In the end, Hadid's team may leave blanks at various access points for other architects to design. But in the conceptual renderings, which are a good deal more specific and legible than Hadid's usual elegant abstractions, the High Line has acquired a seamless, molded-concrete curviness reminiscent of a 1960s flight terminal. Markus Donchantschi, one of Hadid's collaborators, suggested that benches might emerge out of a ramp, become articulated (identifiably benchlike) for a few yards, and then disappear again back into a floor or wall. At the Gansevoort Market, the walkway would slope gently up and end on a rooftop observation deck, giving the building below the cozy, space-age look of the Teletubbies' burrow. Steven Holl The architect Steven Holl, who lives in Greenwich Village near the southern end of the High Line and works near the other end, has been floating plans to salvage it for more than 20 years. His priority now is to get at least a segment of it open to the public soon, so that redeveloping the rest will seem irresistible. Eventually, he hopes to make the High Line part of a green loop connected to the new Hudson River Park by a series of pedestrian bridges that would soar above the fierce traffic of West Street. Holl also hopes to move the West 26th Street flower market down to the meat market, so the smell of blooms rather than blood would fill the wide intersection at Gansevoort Street. A spiraling ramp full of flower stalls would rise above the warehouse building, like a scented lookout turret. The actual lookouts - the security officers monitoring the High Line's full length - would be headquartered in a long glass gallery jacked overhead at 18th Street: a "translucent membrane bridge," Holl calls it. Holl has paid special attention to the rail line's underside, partnering with the artist Solange Fabião to create a 1.5-mile lighting display that could be used for artwork or advertising. Terragram Of all the finalists, it is the Terragram team, led by the landscape architect Michael Van Valkenburgh, that draws the greatest inspiration from the way the High Line looks today: a strip of urban wilderness. In this plan, still painted in broad philosophical brushstrokes rather than architectural details, a narrow concrete walkway meanders past patches of unkempt-looking greenery or a thick forest of sunflowers. The High Line has a particular ravaged beauty, heightened by neglect: Above, according to the team statement, is a "resilient volunteer wildscape," below, the "sublime industrial underbelly of the rail corridor itself." All the architects evince an almost sensual fondness for the High Line's bare steel, the rare frank manifestation of a skeleton that, in tall buildings, is usually hidden. In projects of adaptive reuse such as this one, there is always a balance to be struck between preserving an architectural memory and giving it new life; Terragram's plan celebrates messy history rather than a high-gloss future. That's the crux of the competition. Assuming that in the long run the Friends of the High Line are successful in their quest, the final selection of a master planner will determine just how raw and brutal an old industrial muscle is permitted to remain or how smooth and civilized it will become as it runs through the heart of an ever-more-chic Chelsea. Copyright © 2004, Newsday, Inc. ------------------- August 12, 2004 Gardens in the Air Where the Rail Once Ran By NICOLAI OUROUSSOFF A rendering of the proposed design for the High Line looking south from 22nd Street and 10th Avenue. A rendering of the proposed design for the High Line shows the view at 23rd Street and 10th Avenue. A team of New York-based architects led by Field Operations and Diller, Scofidio & Renfro has been selected to design a master plan that would transform an abandoned section of elevated freight track into a public park that would weave its way north from the meatpacking district to Hell's Kitchen, two stories above the city. The city and Friends of the High Line, a nonprofit group that has been overseeing the development of the High Line elevated track, have yet to officially announce the selection, which was made last week. City officials and members of the architectural team still have to work out the details of a design contract that could eventually encompass a series of public gardens, a swimming pool, an outdoor theater and food halls, a project running for more than 20 city blocks from Gansevoort Street to West 34th Street. Nonetheless, the selection marks a critical step in one of the most compelling urban planning initiatives in the city's recent history. The preliminary design succeeds in preserving the High Line's tough industrial character without sentimentalizing it. Instead, it creates a seamless blend of new and old, one rooted in the themes of decay and renewal that have long captivated the imagination of urban thinkers. Perhaps more important, the design confirms that even in a real estate climate dominated by big development teams and celebrity architects, thoughtful, creative planning ideas - initiated at the grass-roots level - can lead to startlingly original results. As the process continues, the issue will be whether the project's advocates can maintain such standards in the face of increasing commercial pressures. Architects have fantasized about the High Line since at least the early 1980's, when Steven Holl first completed a theoretical proposal to build a "bridge of houses" that straddled the elevated tracks. Property owners considered the line an urban blight, and only a few years ago they were lobbying for its demolition. Friends of the High Line defeated that effort, in part by convincing Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg and city planning officials that a revamped High Line could act as a spur to urban renewal. Eventually, the site was conceived as a public promenade, one that could be used to bind together the communities that lie beneath it. The city planning office, meanwhile, devised a plan that would allow property owners below the High Line to transfer their development rights to other sites within the district. Friends of the High Line has also raised $3.5 million in private money for the project. The city has committed another $15.75 million over the next four years. The strength of the Field Operations design is its ability to reflect a sense of communal mission without wiping away the site's historical character. These competing interests are balanced with exquisite delicacy. The architects begin by creating a system of concrete planks that taper slightly at either end. The planks will be laid out along the High Line's deck in parallel bands, creating a pedestrian walkway that meanders back and forth as it traces the path of the elevated tracks, occasionally fading away to make room for a series of colorful gardens. The gardens embody competing forces - some wild, others carefully cultivated. At various points along the deck, for example, the existing landscape of meadow grass, wildflowers, weeds and gravel will be preserved. At other points, that landscape will be replaced by an explosion of vividly colored fields and birch trees. The idea is to create a virtually seamless flow between past and future realities, a blend of urban grit and cosmopolitan sophistication. But it is also to slow the process of change, to focus the eye on the colliding forces - both natural and man-made - that give cities their particular beauty. That vision has a more subversive, social dimension: to offer a more measured alternative to the often brutal pace of gentrification. There are few better vantage points for observing the city's evolution than the High Line. From the gardens, for example, various views would open up to the surrounding cityscape. Framed by the surrounding buildings, they would offer visual relief from the isolated world above. At the same time, they would set up a rhythm as one strolls along the concrete deck, between spectacular urban vistas and the more contemplative world of the gardens. The tranquility of that experience would be interrupted by a series of carefully calibrated public events. In some places, for example, the concrete path is to dip below the level of the gardens, allowing pedestrians to observe street life below. Above 23rd Street, another section of the deck would peel up to create an informal outdoor amphitheater. Just beyond the stage, a section of the deck would be cut away, creating a stunning view of cars streaming by below. The opening is to be framed by a perfectly manicured lawn - a nod, perhaps, to the more conventionally suburban vision of park planning that extends a few blocks away along the Hudson River. Further to the north, a public swimming pool would be embedded into the deck's concrete surface. Like much of the design, the pool is only a sketch - the beginning of an idea - but it is an intriguing one nonetheless. A large concrete panel lifts up at one end of the pool to support a faux urban beach. Concrete piers extend out into the water like giant fingers. The power of such gestures lies in their simplicity. As architectural objects, they are relatively mundane. Their meaning arises from their relationship to the immediate context. The design's greatest weakness, in fact, occurs when the architecture gets more elaborate. Currently, the High Line ends abruptly at Gansevoort Street, its steel beams and concrete deck protruding above the roof of a warehouse like a severed limb. This would eventually become one of the project's main gateways. The architects have proposed a grand stair that leads up to the gardens, flanked by a gallery space and rooftop market. Just above the market, the large, glass-enclosed form of a bar would jut out over the stair. The idea is to tap into the meatpacking district's vibrant social life in order to energize the High Line's public gardens. But the architecture is bland. And the impulse is at odds with the lightness of touch that characterizes the rest of the design. Worse, it comes perilously close to conventional development formulas: a high-end mall for downtown sophisticates. What one longs for here is a more gentle entry, one that would allow the public to slip into the gardens virtually unnoticed. Such issues can easily be corrected as the design process unfolds. But they point to what may ultimately be the greatest threat to the project's success: regulating access to the site. The High Line has already begun to spark the interest of developers, who understand its potential as an agent for raising real estate values. The developer Marshall Rose is working with Frank Gehry on a proposal for a mixed-use development that would straddle the High Line near 18th Street. The hotelier André Balazs, meanwhile, is negotiating to purchase a site that adjoins the High Line just below 13th Street, a lot that was once slated for a project by the celebrated French architect Jean Nouvel. In an effort to take advantage of that interest, city planners have envisioned a series of incentives that would reward developers who include public access to the High Line in their plans. The scheme would also allow developers to connect commercial ventures directly to the gardens, which could radically alter the nature of the project. At the same time, allowing those who own properties below the High Line to relocate creates the possibility of freeing portions of the High Line from the surrounding density. In their competition entry, the Field Operations architects' only link to outside development is depicted as a drawbridge. They are right to be ambivalent. As the High Line project continues to develop, the issue of access will have to be handled with particular care. If not, the High Line could one day become nothing more than Manhattan's belated answer to the historic theme park - a grotesque urban mall on stilts. But this is not the time for skepticism. So far, both Friends of the High Line and the City Planning Department have proved remarkably adept at negotiatingpolitical hurdles. They have refused to pander to commercial interests. Nor have they ignored them. In selecting the design, they continue to show a genuine sensitivity to the High Line's value to the public realm. After the flawed, often cynical planning efforts that have marked development at ground zero, the thoughtful development of the High Line should be welcomed by New Yorkers who believe decent planning and imaginative architecture have a role in the city's future. Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company -------------------- The High Line — a dramatic park? BY JUSTIN DAVIDSON Staff Writer August 13, 2004 If the budgets and bureaucrats fall into place, the architectural firm Diller, Scofidio + Renfro will transform the High Line, an abandoned railway running above the streets of West Chelsea, into a dramatic strip of parkland. Friends of the High Line, the nonprofit organization leading the effort to recycle that industrial artifact, chose the firm from four finalists including the Pritzker Prize-winner Zaha Hadid, sentimental favorite Steven Holl (who has been agitating for the project for more than 20 years), and a team led by landscape architect Michael Van Valkenburgh. Diller, Scofidio + Renfro's plan offers an irresistible mix of the pastoral and the theatrical. All the proposals dealt with the untamed grassland on the abandoned railway bed, but the winner envisioned an undulating landscape that climbs small hills and dips between the girders. The choice cements the recently exalted reputation of a firm that once inhabited the conceptual edge of the architectural world, working as much with insubstantial materials such as light and electronics as with concrete and steel. The firm has recently scooped up commissions to reshape Lincoln Center and the cultural district around the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Even half a dozen years ago, it seemed implausible that the firm would become such a major player in reshaping the cultural life of an architecturally cautious city. This was, after all, the team that in 2002 produced the Blur Building, a temporary walk-in cloud hovering above a Swiss lake. Among the projects the firm has in the pipeline is the Eyebeam Museum of Technology in Chelsea, where visitors will wander along a ribboning ramp in a wireless high-tech haze and floors will swoop up into walls as they do in a skateboarding park. The firm's High Line design combines the provocative with the practical. An elevated outdoor swimming hole includes a patch of beach on a sloping plinth. A vast outdoor movie screen would be visible from the street — and from bedrooms three blocks away. But the core of the proposal, which is still in the early phase, involves blurring the lines between pavement and wilderness, with plants that burst from between narrow concrete planks. Rather than the neatly divided zones of traditional parks, the scheme aims for a stylish bit of planned dishevelment. There are still major hurdles. The project could cost up to $100 million, which has not yet been raised, and while the city backs the plan, the federal government and CSX, the company that owns the High Line, still need to sign off on it. Copyright © 2004, Newsday, Inc. ----------------- Posted: Wed Nov 24, 2004 8:49 am Post subject: -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- http://www.gothamgazette.com/ Turning The High Line Elevated Railroad Into An Unconventional Park by Ann Schwartz November 11, 2004 In one of his last acts in office, Mayor Rudy Giuliani approved the demolition of the High Line, an abandoned elevated freight railroad running through Chelsea and the West Village. The owners of property shadowed by the hulking structure wanted it torn down. The idea of reinventing the tracks as a public open space, proposed by a grassroots group called Friends of the High Line, was a fantasy that few people gave any chance of success. Fast forward three years. This October, the city announced the selection of a design team to make the track a public promenade, as well as the dedication of $43 million to the project, which has an estimated total cost of between $60 and $100 million. The State of New York and CSX Transportation, the railroad that owns the line, joined the city in petitioning the federal Surface Transportation Board to rail-bank the line, which would transfer the easement to the city and allow its use as public space. If all goes as planned, construction will begin next fall. Against all odds, a crazy and impractical-seeming idea is rapidly becoming a reality. The High Line was built in the 1930s to serve the refrigerated meat and dairy warehouses of the West Side, taking dangerous freight traffic off Tenth Avenue. Part of the line was torn down in the 1960s, and the remaining segment, from Gansevoort to 34th Street, was taken out of service in 1980. It was mostly forgotten, except by architects, preservationists and adjacent property owners. The few people who discovered the rusting track, overtaken by weeds and wildflowers, were captivated by its solitude and mystery. Some likened it to a magic carpet ride -- a tapestry that changed with the seasons, floating two stories high through industrial precincts, just above the streets but open to the sky and river and cityscape. In 1999, West Side residents Joshua David and Robert Hammond founded Friends of the High Line to save the line and take advantage of a rare opportunity to create open space in an area that desperately needed it. To their surprise, they quickly gained the support of local residents, civic organizations, and businesspeople, including the owners of art galleries in West Chelsea. "The power behind the project was that it was a dream, a dream-like vision, we were making a reality," recalled David. "It seemed like something wonderful and impossible. And as soon as people got the sense that this wonderful, seemingly impossible thing was possible, it created incredible excitement." Elected officials started coming on board, including City Councilmember Christine Quinn, who represents the area, and Council Speaker Gifford Miller. A turning point came with the election of Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who quickly reversed the city’s course and began the rail-banking process early in his term. Mayor Bloomberg and Department of City Planning Director Amanda Burden envision the line tying together three areas that are the focus of city revitalization efforts: the Gansevoort Historic District, West Chelsea, and the far West Side between the 30s and 42nd Street, including the site of the controversial proposed stadium complex. Mayor Bloomberg called the High Line "a beautiful new amenity that will serve as the spine of vibrant new neighborhoods on Manhattan’s Far West Side and create new economic benefits in the years to come." A Completely Different Kind Of Park In making their case to preserve the tracks, Friends of the High Line frequently cited the example of the Promenade Plantée, a landscaped walkway on a rail viaduct crossing the 12th Arrondissement in Paris. Reflecting the classic beauty of the city it overlooks, the promenade is a linear formal garden, a path bordered and interrupted by neatly edged beds of flowers, shrubs, and trees. The first park ever built on an elevated line, it has been a huge success, attracting many more visitors than expected and spurring the construction of apartment and commercial buildings in the surrounding area. Although the concept of the High Line as a landscaped pedestrian walkway was inspired by its French predecessor, the design is shaping up to be something different altogether — unlike any other park and unique to New York. "People are looking for a design that refers to the special qualities that are up there now," said David. The goal is to capture the disused track’s wildness, its grittiness, its evocation of the city’s industrial past, and especially its sense of serenity. Yet the park will need to accommodate large numbers of people, a variety of public uses, and the commercial activities that will inevitably arise in the adjacent spaces. After narrowing down 70 proposals to four finalists, a selection committee representing five city agencies and Friends of the High named a design team led by the landscape architecture firm Field Operations and architects Diller, Scofidio + Renfro to create the master plan. The team’s provocative preliminary concept looks more like a work of modern sculpture than a traditional park. It is based on parallel concrete planks that fade in and out of a landscape ranging from gravel and grasses to a more cultivated type of garden. In some sections, the volunteer vegetation and rusting metal of the existing line would remain intact. The architects envision the line as a slow, meandering path that at times dips below or curves above the tracks, with places for both quiet reflection and public activities and events. In October, more than a hundred people came to a community input forum to view a presentation of the preliminary concept and offer their ideas, concerns, and hopes. Most of those attending agreed that the park should be a "slow lane," a place to meander, meditate, and enjoy the views. They noted that there is already a well-used route for bicyclists and skaters just a few blocks away at the Hudson River Park. Other community concerns were safety, enough seating, connections to the river, and guarding against the encroachment of commercial activities. The design team will return to the community with an update on December 2, at the Chelsea Recreation Center. Open Space As A Catalyst For Change Unlike the typical development approach that throws in a park or two as a sweetener to make large new construction projects more palatable to the public, the effort to reuse the High Line starts with the premise that open space can be at the heart of neighborhood revitalization. And in contrast to the city’s top-down plan to build a stadium and redevelop the area just to the north, which has generated tremendous neighborhood opposition, the High Line project is a model of local planning. It began at the grassroots and included the input of local residents and businesses as it evolved. According to Joshua David, there has been a remarkable and productive collaboration among Friends of the High Line and numerous city agencies, including parks, city planning, transportation, and economic development. The Department of City Planning has put together a proposal that weaves the High Line into a larger plan for rezoning West Chelsea. The plan aims to encourage the construction of more housing in the area, yet retain the area’s manufacturing and protect the thriving art gallery district that has emerged between 10th and 11th Avenues. To keep light and air around the High Line, the plan would restrict the heights of adjacent buildings, while allowing their owners to sell development rights that could be used in other parts of the district. It also offers incentives for providing access to the line. The public review process for the zoning change is expected to begin in December. Developers are starting to take interest in the area, as planners had hoped. But along with new development comes the risk of increased commercialization. The challenge going ahead is to make the High Line a true public space – not just a mall in the sky – that captures the excitement of the original vision. Anne Schwartz is a freelance writer specializing in environmental issues. Previously, she was the editor of the Audubon Activist, a news journal for environmental action published by the National Audubon Society, and an editor at The New York Botanical Garden. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Gotham Gazette - http://www.gothamgazette.com/article/parks/20041124/14/1193 Dept of City Planning West Chelsea Zoning Proposal  Highline

Gallery One

Highline

Gallery One Highline Gallery Two

Highline Gallery Two

|

|||||||||||||