|

New York

Architecture Images- Gone Penn Station |

|

architect |

McKim, Mead and White |

|

location |

West 34th Street and Eighth Ave. |

|

date |

1910 |

|

style |

Beaux-Arts |

|

construction |

|

|

type |

Railway station Utility |

| click here for Penn Station gallery | |

|

|

"Any city gets what it admires, will pay for, and, ultimately, deserves. Even when we had Penn Station, we couldn’t afford to keep it clean. We want and deserve tin-can architecture in a tinhorn culture. And we will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed." |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

images |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

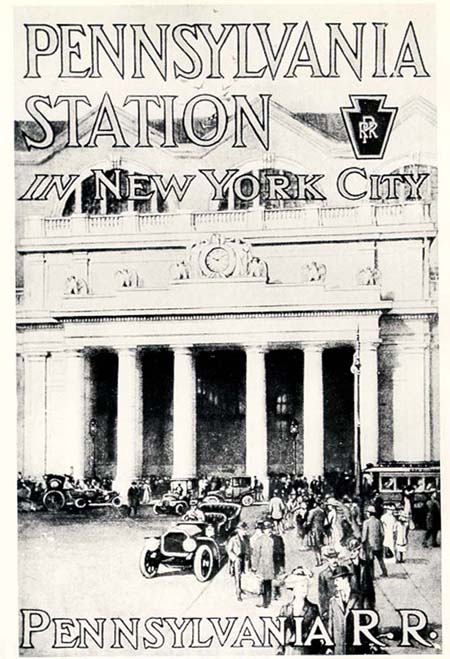

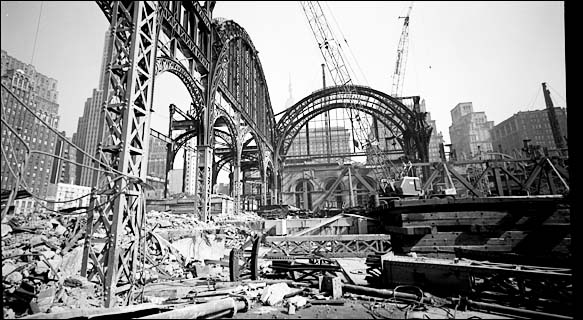

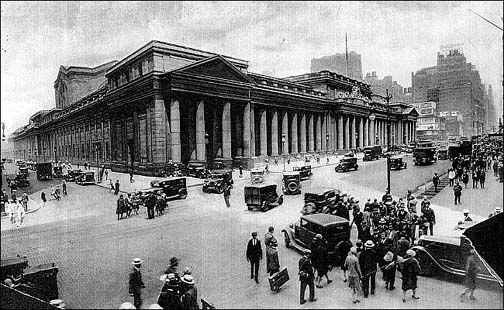

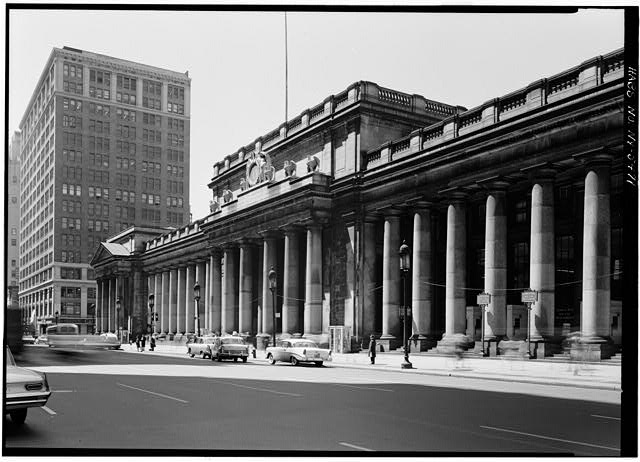

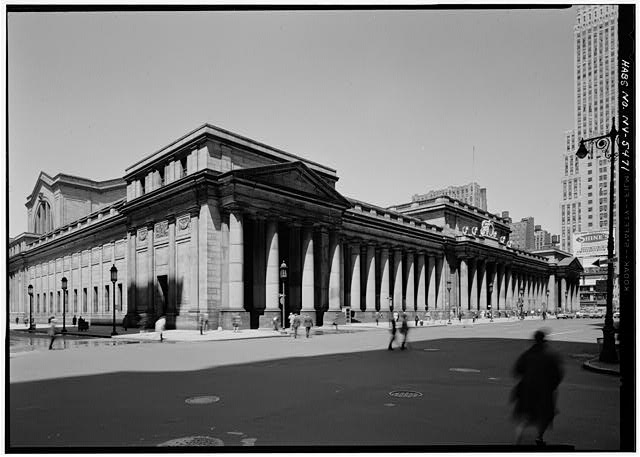

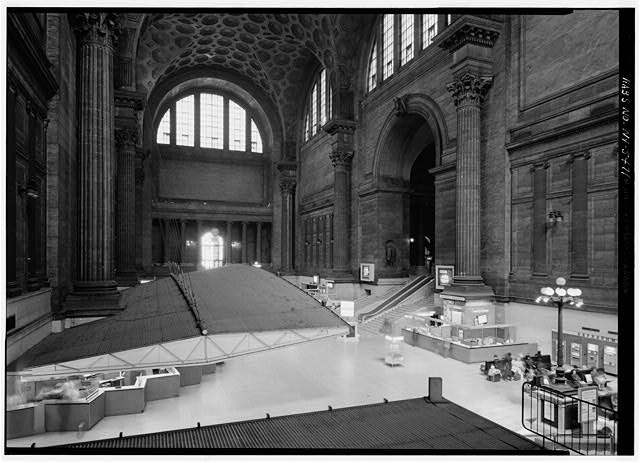

In 1963, one of New York City's finest buildings was demolished to make way for a new $116M sports arena and entertainment complex. Sound familiar? Pennsylvania Station, the monumental 1910 Beaux-Arts masterpiece of architects McKim, Mead and White, was leveled, and replaced with the fourth incarnation of Madison Square Garden. In the 1950s the rise of the automobile and the frenzy of highway building had severely threatened the viability of passenger railways. The owner of Penn Station, the Pennsylvania Railroad, was near financial ruin. In the late 1950s the four blocks of land the station covered in Manhattan had become too valuable not to sell. (Likewise, the automobile's rise precipitated the downfall of the T. Eaton Company, as it clung to its downtown department stores despite the flight of retail shoppers to the suburban malls with their easily accessible free parking.) Meanwhile, the owners of Madison Square Garden were also evaluating their earning potential of their old arena: By 1960, in the eyes of Graham-Paige, it was time to replace the 1925 Garden with a modern, more flexible facility that could handle greater crowds, provide more unobstructed views, and usher in a glitzy new look to attract new audiences. - Plosky p.22 The negotiations proceeded quietly, with little hint that the demise of Penn Station was being contemplated until a New York Times article appeared in July, 1961. The plan called for the demolition of the Penn Station terminal, and its relocation beneath the new arena. It was also revealed that a new corporation, Madison Square Garden, Inc., would manage and own 75% of the building, while the owners of the existing building (the railway) would retain a 25% interest. The proposed arena was hailed as a catalyst for economic development in the area by many in the business community.

These organizations saw in the development of the Penn Station site a way to revitalize the midtown area, which had been begun to languish as postwar suburban construction diverted attention from the city. This fact, coupled with the unparalleled transportation facilities of midtown and the central location of the huge Penn Station parcel, meant that the Madison Square Garden plan would not, in the eyes of the developers, make economic sense on any other site. The Madison Square Garden Corporation and its supporters were therefore quick to dismiss suggestions that the Garden complex be constructed elsewhere in Manhattan. - Plosky p 27But once the plans were announced, public reaction was quick and loud.

Now alerted, New York's architects, artists, and writers were outraged at the prospected demise of such a significant structure. Art and architecture institutions almost uniformly called for Penn Station to be preserved. - Plosky p. 35

Many were angered that Penn Station was being taken down to make way for commercial development. “New Yorkers will lose one of their finest buildings, one of the few remaining from the ‘golden age’ at the turn of the century, for one reason and one reason only: that a comparatively small group of men wants to make money,” wrote the news editor of Progressive Architecture on September 17, 1962. One architect complained that designers beholden to commercial interests threatened the integrity of his profession and offered a suggestion to avoid disputes among architects: Frequently, when we are fighting an avaricious interest, we also have to fight with our own colleagues who conspire with the predators for a fast buck. Perhaps we should have an oath of the type doctors take, which would make it at least hazardous for an architect to conspire against our cultural domain. 46 Several others advocated relocating the new Madison Square Garden complex to another, underutilized site in Manhattan — perhaps to one of the city’s urban-renewal areas. 47 (As noted earlier, these proposals were quickly dismissed.) - Plosky p. 34

Other art and architecture institutions passed judgment as well. The American Institute of Architects opposed the razing of Penn Station; several of its members, as well as the editor of the Institute’s Journal, objected loudly during the controversy. 56 Oculus, the A.I.A.’s New York chapter magazine, bitterly reported that “New York seems bent on tearing down its finest buildings… No opinion based on the artistic worth of a building is worth two straws when huge sums and huge enterprises are at stake.” 57 The Fine Arts Federation of New York, a non-profit alliance of art and architecture groups established in 1895, also protested the plans for demolition, preferring instead “that a study should be made ‘with a view to preserving those qualities of spaciousness and monumentality for which the station is justly famous.’” 58,59 - Plosky p. 36 Ada Louise Huxtable, architecture critic for the NY Times weighed in: "We are an impoverished society. It is a poor society indeed that can’t pay for these amenities; that has no money for anything except expressways to rush people out of our dull and deteriorating cities. 64" Five architects banded together to form the Action Group for Better Architecture in New York (AGBANY). In August of 1962, after assembling a membership of 175 that included Jane Jacobs (close to victory in the battle to thwart Robert Moses and his plan for a Lower Manhattan Expressway, and fresh from publishing The Life and Death of Great American Cities) the group placed an ad in the NY Times which conceded that “it may be too late to save Penn Station.” Nevertheless, the ad declared, “it is not too late to save New York,” and boldly “serve[d] notice upon present and would-be vandals that we will fight them every step of the way.” Readers were urged to demand that politicians make “the preservation of our heritage an issue in the forthcoming campaign.” - Plosky p. 43

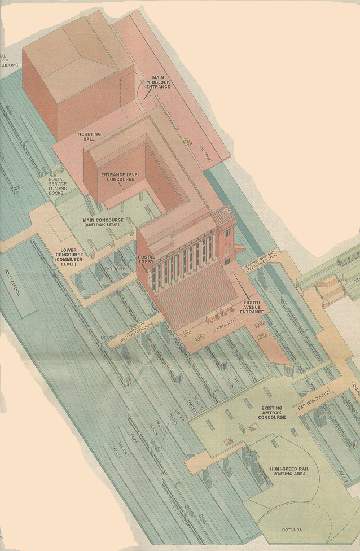

AGBANY, as it had hoped, captured the media spotlight. Its members gave interviews to newspaper, magazine, and television reporters, and succeeded in portraying themselves as determined and civic-minded. Perhaps more importantly, they drew the attention of hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers, who were finally induced to take a long, hard look at the station slated for demolition. - Plosky p. 44 Ultimately, AGBANY lost the battle to save Penn Station. The Planning Commission refused to consider the architectural and historical attributes of the building, and awarded the permits and zoning variances that paved the way for demolition. On October 28, 1963, under the gaze of picketers wearing black arm bands, demolition began. One bright light for preservationists did however result from this episode. AGBANY had galvanised the community into realising that the preservation of significant historical sites was too important to leave to the whims of commercial developers, or to the goodwill of politicians who were not bound by law to defer to the recommendations of historical protection bodies. Ultimately, the legislation required to protect NY's architectural heritage was signed into being in 1965. Subsequent court cases would challenge the constitutionality of this legislation, but it was finally upheld in a 1978 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court. Even by 1966, when the 'ugly work' was done, attitudes toward historic preservation had changed enough that the station was already missed -- Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan refers to Penn Station’s razing as the greatest act of civic vandalism in New York’s history. Ironically, the importance of Penn Station as a transportation hub rebounded. Even though use had dwindled from 109 million people in 1945 to 55 million in 1960, by 1998 the number had risen to 500 million annually, with further growth expected. By the early 1990s it had become apparent that Penn Station, now submerged below the Gardens, was about to burst at its seams. It was realised that a possible solution lay across the street with the Farley Post Office Building, another Beaux-Arts edifice created by the same architects, McKim, Mead and White. This building had been erected shortly after Penn Station, and the rail lines ran beneath it as well. One of the most outspoken critics of the Penn Station demolition had been Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who had a fond attachment to it. He became the champion that pulled together the political will and funding required to turn the Farley Building into a reborn Penn Station. What has emerged is a redesign by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill that incorporates a soaring skylight to recreate some of the grandeur of the original Penn Station. New York was very fortunate to have such a fine building so close by. It had in fact been one of the first buildings to be protected in the aftermath of the AGBANY protests. In the end, the demolition of McKim's Penn Station will have cost the public dearly. A huge sum of money is being spent to resurrect a glimmer of its former glory: The project was budgeted at $484 million in mid-1999; it would be paid for by a combination of federal, state and city money, as well as private funds that would be dedicated to the retail and commercial spaces proposed for the new Farley Amtrak concourse. - Plosky p. 63. |

|

|

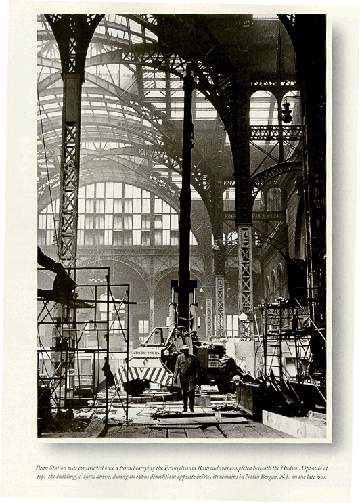

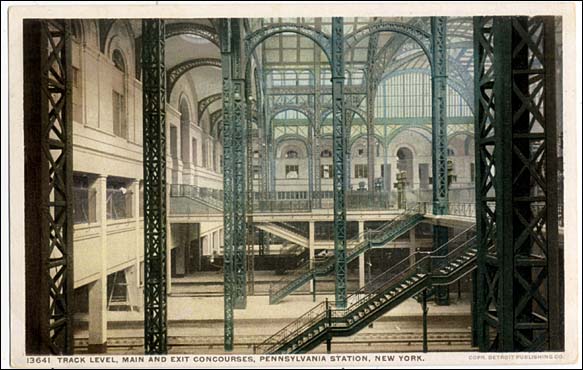

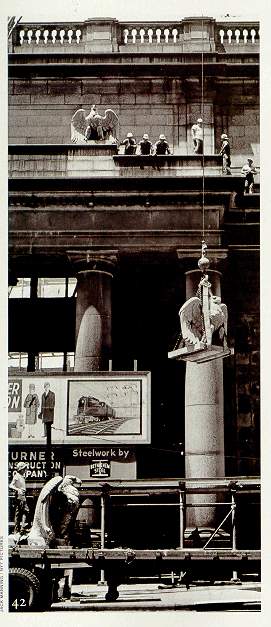

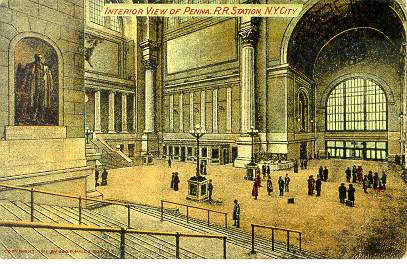

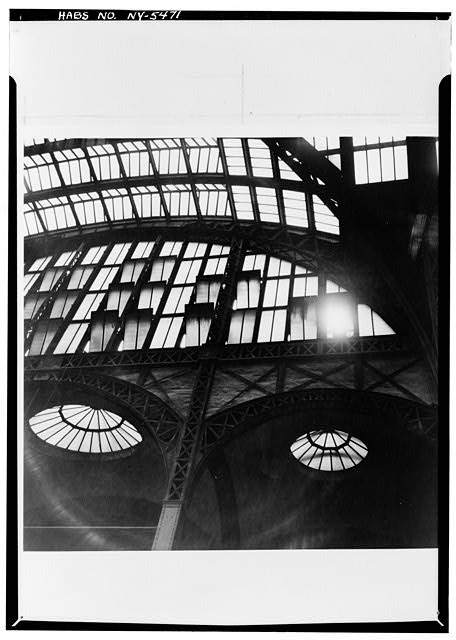

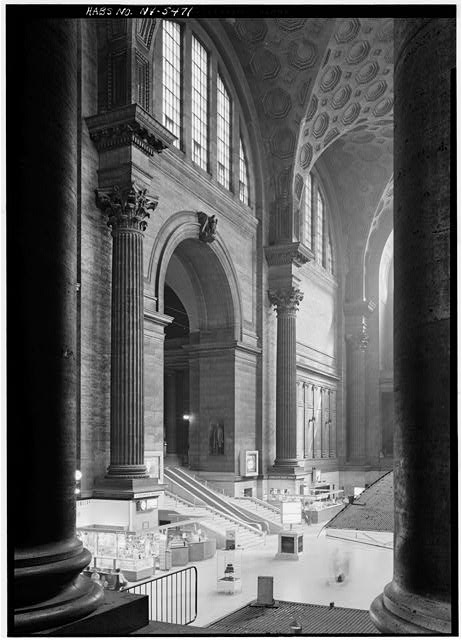

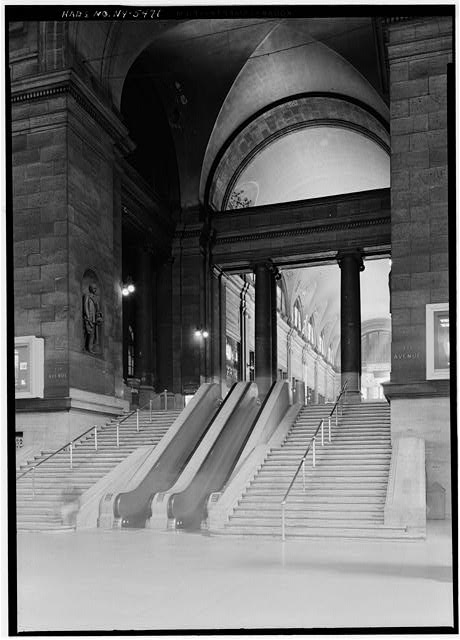

October 26, 2003 URBAN TACTICS The Death and Life of Preservation By TONY HISS The facade of the exuberantly oversized Penn Station had 84 granite columns. Forty years ago on Tuesday, jackhammers began demolishing New York's original Pennsylvania Station, an exuberantly oversized 1910 railroad station that swept travelers and commuters along through a series of ever more spectacular public spaces. A facade lined by 84 massive pink granite columns led those in taxis into a carriageway derived from the Brandenburg Gate, while those on foot traversed a long, coolly elegant, light-drenched Italian-style shopping arcade. Then came a waiting room a block and a half long and 15 stories high that was modeled on, but larger than, an imperial Roman bathhouse. These details, vividly described in Lorraine B. Diehl's book "The Late, Great Pennsylvania Station'' (Houghton Mifflin, 1985), were just the warm-ups, the canapés for the great concourse behind, a room whose complex, extravagantly curved and sinuously arching steel-and-glass-greenhouse roof high overhead brought bright daylight down to platforms and tracks deep in the Manhattan bedrock 45 feet below street level. Even now, 40 years after its disappearance, people can still remember the multilayered effect this room had, the glimpses of destinations no trains could reach. Hurrying about on everyday business, people could at the same time feel singled out. Entering the concourse was somehow like boarding a see-through dirigible that was about to float away, or like a stroll across a forest floor beneath gigantic transparent orchids. And all this just to get on a train! No wonder two generations of New Yorkers took this station to their hearts and felt betrayed by its loss. At the time there was nothing to be done to stop the destruction; the city didn't yet have a Landmarks Preservation Commission. Traditionally, New York had defined itself as the House That Ruthlessness Built, and for more than 300 years the conveniently prevailing assumption had been that whatever got torn down was only making way for something better. No one, after all, had protested in 1903 when 500 buildings had been razed so that Penn Station could go up. This week, a new organization called the New York Preservation Archive Project has reassembled and is honoring the small band of then-young architects, writers and concerned citizens who rose up in the early 60's to object, strenuously and eloquently, to the demolition of the great Prussian-Italian-Roman-Jules Vernian train station. It's generally acknowledged that their efforts, together with the quieter, longstanding work of neighborhood groups in Greenwich Village and Brooklyn Heights, helped secure the creation of the city's Landmarks Commission in 1965. Thirteen years later, in 1978, the legality of landmarking was ringingly upheld when the United States Supreme Court ruled that the commission had acted properly in 1969 by forbidding the destruction of New York's other superlative train station, Grand Central Terminal. Today the Landmarks Preservation Commission has officially protected 1,100 individual landmarks, including the Empire State Building, Central Park and, more recently, Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn. It has also set up 81 historic districts in all five boroughs, including Cobble Hill in Brooklyn; Jackson Heights, Queens; and, in Manhattan, SoHo, the Upper East Side and, recently, the Gansevoort Meat Market. And there is more to celebrate. Anthony C. Wood, founder and chairman of the Preservation Archive Project, said that when landmarking became official, so did hope. "It's not routine or easy," Mr. Wood said. "You still have to fight madly, but now it's not inevitable that some beloved building is programmed to be lost." Thanks to the Penn Station protestors and other preservation pioneers throughout the city, the way change comes to New York has been transformed. Most of New York's buildings are still destined to be short-lived, at the mercy of whims and impatience and sudden changes in investment strategies. We all indelibly learned in September 2001 that hatred can change the skyline in an hour. But within the blur of constant change we've been able to set up a pattern of permanency, and are now anchored by the places we can count on. Which means that when we look along Lexington Avenue, for instance, and admire the way the early morning sun turns the silvery Chrysler Building spire to gold, we can also look ahead to mornings long after our own time when others will be moved by the same sight. All this has happened because around the time that the old Penn Station was being torn apart, something was evolving within New Yorkers. People had begun to love the city for what it already made available rather than for what it might eventually become. In that moment, New Yorkers found a new bedrock inside themselves, and that's not likely to change. Tony Hiss's works include "The Experience of Place'' and, with Rogers E. M. Whitaker, "All Aboard With E. M. Frimbo.'' His next book, "From Place to Place,'' to be published by Knopf, is about exploring the travel experience. Voices From the Wilderness Unite By JIM O'GRADY To mark the 40th anniversary of the day the first wrecking ball struck Penn Station, the New York Preservation Archive Project, a nonprofit group, has been trying to contact everyone involved in efforts to save the station. The group has identified 300 people who marched, wrote letters, signed newspaper ads or spoke at hearings. Anthony C. Wood, the group's director, believes that at least 65 of them have died, but his group hopes to contact 100 others, and at least 20 will be honored Tuesday at an event at the Century Association. The group plans to take oral histories from them at that time. Here are recollections of three original protesters. Robert Venturi The architect Robert Venturi, the 1991 winner of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, loved the old Pennsylvania Station. When he was 5 or 6, his father used to take him to a spot overlooking the famous hall based on the Roman Baths of Caracalla. "That was it, my whammo introduction to the great Penn Station," he said. Mr. Venturi, now 78, calls the building, "one of the great interior spaces in the history of the continent." He was part of the small group that picketed outside Penn Station on Aug. 2, 1962, and he spoke at a City Planning Commission hearing on the station's fate in January 1963. Jane Jacobs Jane Jacobs's landmark book, "The Death and Life of Great American Cities," had been out for a year when she joined some 200 protesters on the steps of Pennsylvania Station that August day in 1962. The book's central theme of preserving what makes a city unique, including one-of-a-kind places like Penn Station, had caught on with many readers, she said, "but it hadn't yet caught on with planners and city officials." "There was no exhilaration to this kind of thing," Ms. Jacobs, 87, said of the protest. "It was more like a wake. The city was making everyone's life absurd with its goofy decisions." Laurel Lovrek In 1962, when Laurel Lovrek of Cleveland was a freshman at Cooper Union School of Architecture, an early assignment was to go to Pennsylvania Station with her fellow students and draw what she saw. "In the brief time I was in the building, I really fell in love with it," said Ms. Lovrek, an architect who lives in Princeton, N.J. "It was the way trains used to be in those old black-and-white movies." She joined the picketers because a professor had told her to go. "I felt pretty good about what I was doing,'' she said, "but I remember we were ignored by the general traffic on the streets of the city that day." Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company October 28, 2003 40 Years After Wreckage, Bits of Old Penn Station By GLENN COLLINS Workmen haul down the two-ton stone eagle from the facade of Pennsylvania Station October 28, 1963. An early postcard shows the concourse of the old Pennsylvania Station. Forty years ago today at 9 a.m., in a light rain, jackhammers began tearing at the granite walls of the soon-to-be-demolished Pennsylvania Station, an event that the editorial page of The New York Times termed a "monumental act of vandalism" that was "the shame of New York." This grim anniversary falls in Halloween week, when spirits of the departed seem so notoriously restive, and those searching for the insistent phantoms of Penn Station can find them deep in the bustling, claustrophobic warren that has been carved out of the old terminal's subterranean remains. Ghost hunters need only know where to look. Consider, for example, the eroded splotch in the new imitation tile floor down a corridor off the station's busy rotunda. Peeking through, and clearly visible, are exposed blocks of surviving pink Milford granite, adjacent to a section of the original tan herringbone-patterned bricks that once supplied the paving for Penn Station's southern carriage drive. Horse-drawn buggies — not to mention Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey and five decades of passengers — traversed bricks identical to these as they rushed to waiting trains. "It's as if the old station just keeps insisting on coming out," said John Turkeli, a railroad historian and urban archaeologist who leads a free monthly public tour of both the Penn Station that is and the spectral Penn Station that was. It is true that the wrecking ball knocked down nine acres of travertine and granite. But thousands of distracted visitors to the current terminal have no idea that they are surrounded by dozens of minor treasures from the vanished masterpiece by McKim, Mead & White. If some Penn Station revivalists see only the tragic loss of architectural grandeur in such fragmentary and accidental survivals, Mr. Turkeli, 43, sees them as evidence of the indomitable spirit of the transportation hub, which opened to the public in 1910. "It just will not be forgotten," he insisted. Daniel A. Biederman, president of the 34th Street Partnership, said he started the architectural tours a decade ago "to increase people's awareness, so that more great things won't be destroyed." The partnership sponsors the tours under the umbrella of the Business Improvement District, which runs along 34th Street from 10th Avenue to Park Avenue South. "When you see these vestiges of this famous place, you feel even more regret," he said. Some of the remains were identified by Lorraine B. Diehl, who used to lead the tours, and others were discovered by Mr. Turkeli. Those who wish to join Mr. Turkeli's 90-minute tours should gather at 12:30 p.m. on the fourth Monday of every month at the tourist information booth in the station's rotunda; information is available at (917) 438-5123. But since the next tour will not be until Nov. 24, ghost seekers can, on their own, find many of the surviving artifacts by investing a bit of time and shoe leather. (However, visitors must wait for the tour to see a few inaccessible relics in restricted areas protected by station police.) A visit to Penn Station — which gave way to the Penn Plaza complex and Madison Square Garden — might begin outdoors at the statue of Samuel Rea, president of the Pennsylvania Railroad from 1913 to 1925, in front of 2 Penn Plaza at Seventh Avenue and 32nd Street. The statue, by Adolph A. Weinman, once stood in a niche to the right of the staircase leading down into the main waiting room. Next, head south on Seventh Avenue toward 31st Street, and make obeisance to one of the original 5,700-pound Tennessee-marble stone eagles that once perched on ledges above the station's grand entrances. This eagle is in captivity now, fenced in, visited daily by a family of squatter pigeons. Could they be distant descendants of the flock that once decorated Penn Station's exterior and flapped under its vaulted roof? On 31st Street, head west to the middle of the block, and pause to look south, across the street, at the monumental surviving edifice of the coal-fired Penn Station power plant, now used for storage and backup power systems. Between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, head north under the canopy along the footpath of the driveway (now barred to vehicles for security reasons). Make a left into the terminal building, then pause atop the escalators. This is the location of the original grand staircase into the main waiting room; the Rea statue was once enshrined at the right. Look down at the rotunda below, site of the old main waiting room. It was patterned after the Baths of Caracalla in Rome and once soared 15 stories to a vaulted ceiling. The big room, Mr. Turkeli noted, "then as now, never had a bench in it." "It has never really been," he said, "a place to wait." After descending on the escalator, head left to a corridor marked "For Passenger Concourse Use Only," adjacent to the Grove Snack Shop. If it is between 6 and 10 a.m., or 4 and 8 p.m., it is permissible to stroll halfway down the corridor to view the eroded section of the previously mentioned floor tiles and see the remains of the building's signature granite and its herringbone bricks. Another section of these bricks has struggled out from under the asphalt on the opposite side of the rotunda. Without entering the off-limits corridor marked "Employees Only," visitors can stand at the portal and observe, back near the elevator, a swath of the remnant of the station's northern carriage drive. Back at the center of the rotunda, the futuristic waiting room for Acela and Metroliner trains occupies the former men's and women's waiting rooms. At the site of the current departure board, with its tiny digital clock, once stood a windowed arch beneath a large ticking station clock. Walk left, skirting the curve of the glass-enclosed waiting room, and head straight back to the far wall, at the West Gate of Tracks 5 and 6. There, heading down to the train level, is a remaining original staircase of brass and wrought iron (all the others have been replaced by escalators). Walking left to the baggage-claim signs, visitors will see a 1948 bronze plaque that had been affixed to the original station walls, honoring baggage-department employees who died in World War II, from Joe R. Adams to Frederick W. Zahodnick. Behind the wall, in the baggage area restricted to the public (but visible on Mr. Turkeli's tour), are four poignant artifacts of the Penn Station past. Upon the floor survives a section of the original glass bricks that brought natural light from the station's skylight down to the passageways and train level. Nearby, on the original wall of ceramic tile, a fading painted directional sign to the East Gates is still visible. The "E" and "G" have surrendered to time, leaving the Scrabblish message "AST ATES." Next to a wall is what is believed to be the last surviving elevator cage, with its dusty grill. And nearly obscured behind an Everest of heating ducts is the surviving cast-iron train indicator for Track 1. Outside the baggage area, in the public corridor paralleling the modern row of Amtrak ticket windows, an impromptu gallery of historic photographs has been affixed to the pillars. Depicted are the original waiting room, a station facade and 1910 pictures of the vaulting, 10-story-high main concourse, with staircases plunging to the train level, like the one at Tracks 5 and 6. "There's a lot of interest in these photos," said Michael J. Gallagher, the assistant superintendent of station operations, as he stood near one at the pillars. "People study them, and they constantly ask us why the station looks like it does now." So, what is his habitual answer? He sighed, "What can I tell you?" Those interested in a longer visit should head down the stairs past the train announcer's booth into the Long Island Rail Road station. To the right, after the long corridor toward Seventh Avenue, the sleek new ticket windows (under the destination boards) are just about where the old ones were in the original station. Also from the original station, a 30-foot-wide, Tuscan red, cast-iron partition, with beveled-glass windows, stands guard at the portal for the ticketed waiting area, adjacent to the gray police booth under the American flag. After leaving Penn Station, visitors should also seek out the street-level entrance to the Long Island Rail Road terminal on 34th Street near Seventh Avenue. There, they can find a working four-sided clock, suspended on cables and believed by Mr. Turkeli to have been in the original Long Island terminal. Those who have completed the tour, and have been saddened by an architectural loss of such immensity, might appreciate a bit of cheering up. In the end, the destruction of what the Municipal Art Society termed "one of the great monuments of classical America" led to the creation of the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1965. "And that led to the rescue of Grand Central Station," Mr. Turkeli said, "which could have met the very same fate." Part of the demolition of the old Pennsyvania Station in March 1964. The station opened to the public in 1910.  The only remaining original staircase is made of brass and wrought iron. All the others have been replaced by escalators. Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company The Late, Great Penn Station: http://powwmedia.com/pennsy/ Here's an old column from the archives of the New York Times written by Ada Louis Huxtable, commemorating the 31st anniversary of the demolition. Let me fully cite this first, since it is material you would normally have to pay for: Huxtable, Ada Louise. “On the Right Track.” New York Times, 28 November 1994, sec. A, p. 17. On the Right Track By Ada Louise Huxtable; Ada Louise Huxtable is an architectural historian, critic and consultant. Thirty-one years ago, the shattered marble, travertine and granite columns, caryatids, gods and eagles of Penn Station -- modeled after the monuments of ancient Rome by McKim, Mead and White and built for eternity in 1910 -- were carted off to the Secaucus meadows, giving New Jersey undisputed title to the world's most elegant dump. Of the eagles that crowned the station's walls, a few tokens were reinstalled in front of the new Madison Square Garden, making the contrast between classical and cheesy terminally (pun intended) clear. Because what goes around comes around, usually so that you want to laugh or cry, there are plans for a new Penn Station. The proposal is part of a program in which all of the facilities for Amtrak, New Jersey Transit and the Long Island Railroad will be coordinated for what is now fashionably called intermodal transportation but looks more like a railroad revival and great train station renaissance. In addition to vastly improved and expanded services, each rail unit will be given a "presence" -- something Stanford White and his partners knew a thing or two about. And since what goes around comes around in curious ways, the new Penn Station will be created in another classical building by McKim, Mead and White: the James A. Farley Post office, a designated New York City landmark just behind the present station, which has been declared obsolete by the Post Office and semi-surplus property by the Federal Government. Central to the project is the creation of a large new concourse, reminiscent of the scale of the bulldozed terminal. Because the rail yards continue beneath the Post Office building, the conversion is practical. But it is just as much about lost glory as future needs. The Post Office is a gargantuan box of die-stamped classicism that occupies the two full blocks between 31st and 33d Streets and Eighth and Ninth Avenues. It was built in two stages: the first, in 1913, extended halfway to Ninth Avenue; an annex, added in 1935, filled out the enormous double block. The original facade's nonstop 53-foot-high Corinthian columns and anthemion cresting topping a two-block sweep of granite steps was repeated and wrapped around the addition for what must surely be the most redundant colonnade in architectural history. This competent piece of Beaux Arts boiler-plate isn't in the same league as the old Penn Station. But today its acres of space and irreplaceable materials and details are solid gold. The Post Office will keep the arcade along Eighth Avenue, where 7,000 people a day come through bronze doors under an arched ceiling decorated with the seals of the countries belonging to the postal union. One hopes that the nicely browned WPA murals of the city at the north and south ends will remain. The plans for the new station, which will incorporate the redesigned present facility, have been under study since the 1980's by an alliance of railroad, postal service, real estate, construction and Government interests, led by Amtrak and the Tishman Urban Development Corporation. The architects are Hellmuth, Obata and Kassabaum, a large firm experienced in the kinds of major undertakings with which such consortiums feel comfortable, working with a consultant on historic architecture, Jan Pokorny. The cost is budgeted at an optimistic $300 million -- one-third Federal, one-third city and state and one-third to be supplied by Amtrak. Under the enthusiastic sponsorship of Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, half of the Federal commitment, $50 million, had been appropriated before the Republican upheaval that will replace the Senator as head of the Finance Committee in January. With Federal funding halfway home and agreements signed by the city and state, the odds still look good. Behind the "rebirth" of Penn Station is a 25-year story full of the twists of fate and fortune that give economists and futurists a bad name. Who could have predicted the knockout blow that air travel dealt to rail travel in the 50's and 60's? Or foreseen the postmodern crisis in architecture that sensitized architects and the public to the losses of the past? The majestic urban terminals, too expensive to operate and functionally obsolete, were abandoned to decay or demolished as prime sites "ripe for redevelopment" -- the real estate mantra of the times. The decline of the railroads paralleled the rise of the shopping mall, the growth of the preservation movement and the birth of the "festival marketplace." Recycled railroad stations, once left for dead, became filled with shops and restaurants and a notable preservation success. But this was an odd triumph in which the tail wagged the dog: retailing was the prime use and purpose, and train service was peripheral, if it existed at all. For years, Washington's Union Station rained debris from its magnificent barrel-vaulted ceiling ringed with heroic statues into a hole in the ground meant for a visitors' center that came to nothing. Train service was relegated to a kind of outhouse in the rear. Today this is one of the country's most successful indoor malls, but the trains are still out back. Real change came in the 1970's, when Government action to save the railroads brought grants and subsidies for operation and terminal upgrading. As ridership increased, station renovations put the trains up front again. Concourses were no longer treated as real estate opportunities. And while retail has become an important source of revenue, it is now supportive rather than primary. After a spectacular century of highs and lows, the great railroad station is being redefined. That redefinition recognizes and restores the tradition of public space -- the "waste space" of bureaucrats and bean counters. The early, published proposal for Penn Station's new central concourse as an enormous space frame covering the area of the Post Office's huge, skylit mail-sorting court was more Buck Rogers than McKim, Mead and White; it has gone back to the drawing board. The future roof will rise as high as cautious preservation agencies permit, but height is essential here. The court's original skylight never soared, in any sense. The Post Office is more like a classical corset for new construction than a creative inspiration. (For that, one should see Rafael Moneo's stunning and sympathetic additions to the superbly restored railroad station in Madrid.) Meanwhile, at Grand Central a restoration and revitalization plan of exemplary quality by the architects Beyer, Blinder, Belle is forging ahead. New York's other great terminal has survived its own threats, including a traumatic proposal to build a gargantuan tower of aggressive vulgarity on top, the cruelest of jokes on its Beaux Arts splendor. This was fought up to the Supreme Court, winning a substantial victory for the city's landmark designation. Over the years, grime and neglect obscured the constellations of the 125-foot-high concourse ceiling, light ceased to filter through the immense arched windows and the bulbs of the mammoth chandeliers disappeared and dimmed. Government money, the return of rail travel and the upgrading of revenue-producing commercial space have contributed to the ongoing and outstanding restoration and improvement of the terminal's technical, structural and architectural elements by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and Metro North Railroad. With the east balcony free of Kodak's full-color sabotage, a new stair is planned to match the existing stair to the Vanderbilt Avenue balcony on the west, for access to restaurants in the underused balconies and mezzanine. The addition is in the spirit and letter of Warren and Wetmore's brilliant 1903 to 1913 classical design. But only a faithful replica of the present stair will do. To sit at the one small restaurant on the west balcony is to long for more. Rising into those vast heights is the buzz of all the voices of travelers and transients mingling in the upper air. Shafts of sunlight pierce long shadows, spotlighting the moving figures on the floor. The soft, susurring sound transforms activity and motion into a shared experience; it contains the timeless promise of the city's, and the world's, pleasures and adventures. This is the essence of urbanity. Copyright 1994 The New York Times Company Reading this article reminds me that this redevelopment project has now languished for an amount of time longer than it took to build the original station. Planning was begun in 1902, tunneling in 1904, work on the station building in 1906, and the whole thing opened in the autumn of 1910.

|

|

|

Streetscapes/'The Destruction of Penn

Station';

A 1960's Protest That Tried to Save a Piece of the Past By CHRISTOPHER GRAY Published: May 20, 2001, Sunday A NEW book on New York's most famous demolished building -- ''The Destruction of Penn Station'' ($40, Distributed Art Publishers), a series of demolition photographs by the late Peter Moore -- brings back memories of the failed effort to save the renowned structure. These days, four decades later, there would be no shortage of bodies to sit in front of the bulldozers. If there had been as much support in 1962, that era's small group of young, earnest and optimistic protesters just might have won. The architectural firm McKim, Mead & White's Pennsylvania Station was the last word in modernity -- in 1910. But as rail travel declined in the age of airlines and subsidized highways, new monuments to transportation were built not by railroads but by their competition, with buildings like Eero Saarinen's soaring T.W.A. terminal, completed in 1962 at what is now Kennedy International Airport. Although the Pennsylvania Railroad made some improvements, it lost interest in its giant Classical structure, and in 1961 announced plans to demolish the old station for office buildings and a new Madison Square Garden with a swooping, circular roof and a new station below -- a motel-quality version of Saarinen's terminal. The magazine Progressive Architecture was immediately critical of the project and especially of the proposed loss of Penn Station. At that time there was no landmarks law in New York City, no mechanism for protecting structures of public interest. Protests immediately came from modern architects like Hugh Stubbins, Robert Geddes and Percival Goodman, whose works -- including Mr. Goodman's Fifth Avenue Synagogue at 5 East 62nd Street -- seemed the antithesis of the giant limestone station. In contrast, Harmon Goldstone, then the chairman of the Municipal Art Society and later the chairman of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, wrote Progressive Architecture in October 1961 that he was concerned not with the past but with the future. ''Is the proposed new building, for its own purpose in its own idiom, going to be as inspiring a design as McKim, Mead & White's?'' he asked. And he answered, ''There is no reason why it cannot be.'' In early 1962 a meeting of the New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects led to continued protest. ''I called my architect buddies, Peter Samton and Jordan Gruzen, and we all went down to the A.I.A. meeting,'' said Diana Goldstein, who was then Diana Kirsch and working as an architect in the office of Herbert Oppenheimer. The young architects were bitterly disappointed -- the A.I.A. ultimately endorsed a proposal to save only the columns from the station. WALKING out, it was Mrs. Goldstein who challenged her male comrades. ''They're not going to do anything,'' she said of the chapter. ''Why don't we form our own group?'' The three got other modern architects to join, among them Norman Jaffe and Costas Machlouzarides -- Mr. Machlouzarides subsequently designed the Calhoun School, at 81st Street and West End Avenue, which resembles a giant television set. With the architect Norval White -- slightly older than they were and, they said, more politically astute -- as chairman, the group took the name Agbany, for Action Group for Better Architecture in New York. Its headquarters were in Mr. White's apartment at 33 East 61st Street. They wrote letters and circulated petitions for signing, but they faced many obstacles. First, there was no precedent for saving a large commercial structure -- in the early 1960's historic preservation still meant house museums and ancient sites. Second, most defenses of Penn Station were hampered by apologies for what was termed its eclectic character -- no matter how noble, it just did not seem to fit into the brave new world of modern architecture. Third, it was difficult to rebut charges that the station was not functional -- although no one seemed to mention that an air terminal designed, like T.W.A.'s, with the shape of a bird's wings was not necessarily functional. After several months, Agbany decided to picket the station, attracting high-profile supporters like the art critic Aline Saarinen (the widow of the T.W.A. architect, who had died in 1961) and the architect Philip Johnson. Mr. Gruzen, now in partnership with Mr. Samton (at Gruzen Samton), remembers the euphoria of raging against a corporate machine. ''It was like college,'' he said. ''We were painting protest signs, making fliers; it felt like an underground cell.'' At 5 p.m. on Aug. 2, 1962, at least 100 people joined a picket line with signs reading ''Shame'' and ''Don't Amputate -- Renovate.'' An advertisement in The New York Times boldly stated that the group was formed to ''serve notice on present and future would-be vandals, that we will fight them every step of the way.'' THE unusual protest attracted broad press coverage, even on television, but the organizers had trouble moving from goals -- like persuading the Port of New York Authority, as the agency was then known, to take over the station -- to actual results. Mr. Samton remembered that ''as far as most people were concerned, we were a flaky group, a bunch of kids who didn't know what the real world was all about.'' Representative John V. Lindsay supported them, but Mayor Robert F. Wagner was no help, especially after Geoffrey Platt, the mayor's head of an initial landmarks advisory group, said in April that it was ''too late'' to do anything. Agbany's hopes finally rested on a vote by the City Planning Commission, whose approval of a variance was necessary for the new project. But in early 1963 the commission approved the plan unanimously. The commission members included Mr. Goldstone of the Municipal Art Society. There was a second picket line, in October 1963 -- as demolition began. The three original organizers look back bleakly at their effort. ''We just didn't know what we were up against,'' Mr. Gruzen said. Mr. Samton said they never connected with the existing historic-preservation groups, which were nervous about social activism. ''They seemed interested in whether they had connections to the upper class that might be hurt,'' he said. ''They weren't interested in Penn Station -- it was old and dirty.'' But the loss of the old station was a factor in the creation of the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1965. Mrs. Goldstein, now an artist living in San Francisco, said that the missionary zeal of their drive to save Penn Station was related to the missionary-zeal atmosphere of modern architecture in the 1960's. ''And when I found out that great architecture couldn't save the world,'' she said, ''that was a devastating blow.'' She still loves railroad stations. ''In January,'' she said, ''I had a plane ticket to Chicago, but I took the train anyway -- the railroad has much more romance.'' But there's one exception. ''Every time I go to Penn Station,'' she said, ''I cringe.'' Published: 05 - 20 - 2001 , Late Edition - Final , Section 11 , Column 1 , Page 9 Copyright New York Times. |

|

|

|

| GREYHOUND BUS

TERMINAL 244-248 West 34th Street JULY 14, 1936. In the 1930s, bus travel was a new industry, which provided passenger service that was cheaper and more flexible than the railroads. Built in 1935 across the street from McKim, Mead & White's monumental Pennsylvania Station (1910), the streamlined Greyhound Bus Terminal was the perfect symbol for this modernization of travel. Abbott photographed the bus terminal from the Pennsylvania Building at 225 West 34th Street. This mundane office building still stands, but the terminal was replaced in 1972 by the huge, undistinguished office building 1 Penn Plaza. The same day she photographed the terminal, Abbott made several exposures of the interior of Pennsylvania Station. She avoided the station's grand marble staircases and academic murals and concentrated on the glass-roofed concourse, which accessed the track platforms. Working in the early morning when the concourse was almost empty, she focused on the complex geometries of steel and glass. Although she made proofs of two Penn Station images and assigned a researcher to the file, Abbott discarded the subject from the project. After the old Penn Station was demolished in 1966, these discarded photographs became some of Abbott's best known. Special thanks to the Museum of New York, www.mcny.org |

|