|

New York

Architecture Images-Harlem and the Heights Cathedral of Saint John the Divine |

|

architect |

Heins & La Farge [1892-1911]; Cram and Ferguson, Carrere & Hastings, Thomas Nash and Henry Vaughn [1911-1942]; James Bambridge [1979-present] |

|

location |

Amsterdam Avenue and 112th Street, |

|

date |

1892 |

|

style |

Gothic |

|

construction |

stone |

|

type |

Church |

|

|

|

|

|

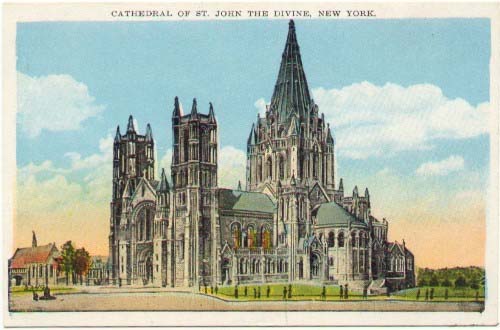

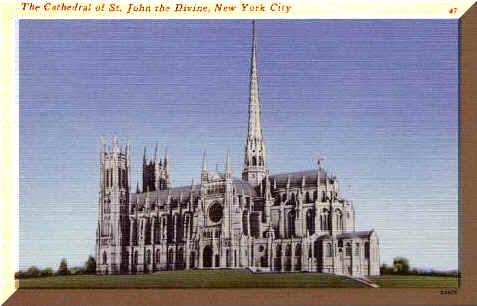

| The Cathedral of St. John the

Divine is a great and beautiful landmark inside, but its exterior leaves

much to be desired, particularly its surroundings, which were supposed to be

green open space as shown in this picture. Currently, there are parking lots, construction equipment, and a huge stoneyard, which is currently under litigation. The structure is missing most of its towers, including the main one. It is said that to finish it would cost $100 million, and possibly take as long as for the originals in Europe, i.e. several hundred years. We hope not, particularly since our other great local church, Riverside Church, is already finished, thanks to modern construction techniques and Rockefeller money. The Cathedral began with a design contest in 1888, won by the architectural firm of Heins & LaFarge. Due to the difficult site, which required a vast foundation and crypt, dedication of the first small section was only possible in 1911. By this time, the Byzantinesque aspects of the interior had become unfashionable and were modified in the direction of English Perpendicular Gothic. Upon the death of Heins in 1907, architect Ralph Adams Cram was brought in and began to take the great nave in a French Gothic direction. |

|

|

images |

|

Construction...

Results, outside...

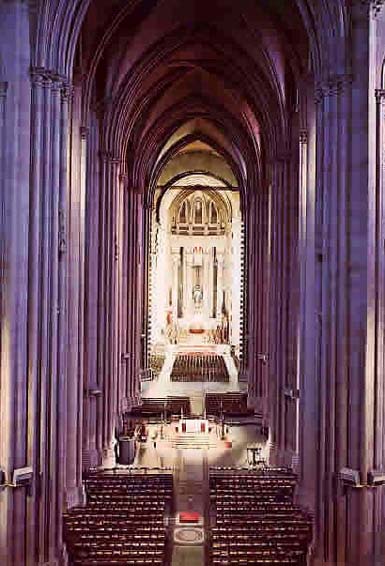

And in...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

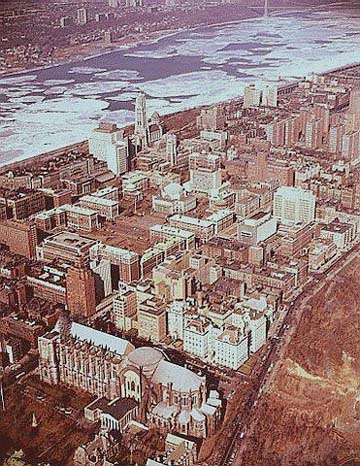

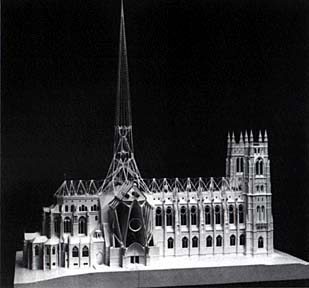

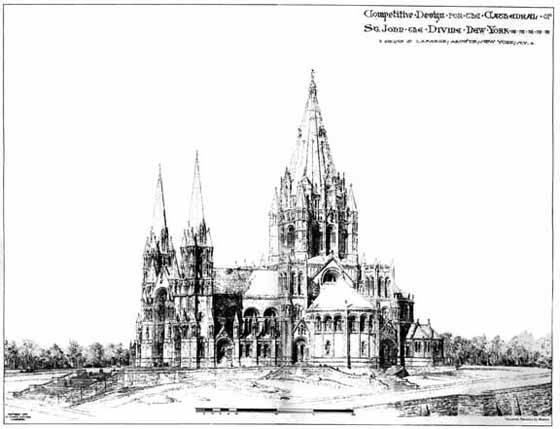

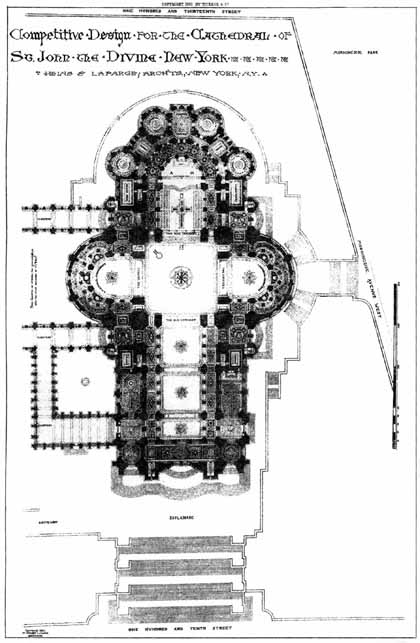

The Cathedral of St. John the Divine, officially the Cathedral Church of

Saint John the Divine in the City and Diocese of New York, is the

Cathedral of the Episcopal Diocese of New York. Located at 1047 Amsterdam Avenue New York, NY 10025 (between West 110th Street, which is also known as "Cathedral Parkway", and 113 Street) in Manhattan's Morningside Heights, the cathedral is claimed to be the largest cathedral and Anglican church and third largest Christian church in the world (although the title is disputed with Liverpool Anglican Cathedral). The cathedral, designed in 1888 and begun in 1892, has, in its history, undergone radical stylistic changes and the interruption of the two World Wars. It remains unfinished, with construction and restoration a continuing process. History An unbroken piece of property of 11.5 acres (47,000 m²), on which the Leake and Watts Orphan Asylum had stood, was purchased for the cathedral in 1887. After an open competition a design by the New York firm of George Lewis Heins and John LaFarge in a Byzantine-Romanesque style was accepted the next year. Construction on the cathedral was begun with the laying of the corner-stone on December 27, 1892, St. John's Day. The foundations were completed at enormous expense, largely because bedrock was not struck until the excavation had reached 72 feet. The first services (in the crypt, under the crossing) were held in 1899. The original Byzantine-Romanesque design was changed to a French Gothic design after the large central dome made of Guastavino tile was completed in 1909, so that while the nave and apse are both rendered in the Gothic style, the crossing under the dome is still Romanesque. The premature death of George Heins in 1907 left the Trustees unsure of how to proceed with the surviving architect, John Lafarge alone. In 1911, the choir and the crossing were opened. At some point, the dome and crossing are intended to be taken down and a massive Gothic tower is to be erected. The first stone of the nave was laid and the west front was undertaken in 1925. The first services in the nave were held the day before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Subsequently construction on the cathedral was halted, because the then-bishop felt that the church's funds would better be spent on works of charity, and because America's subsequent involvement with the Second World War greatly limited available manpower. The Very Rev. James Parks Morton, who became Dean of the Cathedral in 1972, encouraged a revival in the construction of the Cathedral, and in 1979 the Rt. Rev. Paul Moore, Jr., then Bishop, decided that construction should be continued, in part to preserve the crafts of stonemasonry by training neighborhood youths, thus providing them with a valuable skill. In 1979, Mayor Ed Koch quipped during the dedication ceremony, "I am told that some of the great cathedrals took over five hundred years to build. But I would like to remind you that we are only in our first hundred years." One architect who worked for Cram and Ferguson as a young man, John Thomas Doran, eventually became a full partner,( Cram and Ferguson became know as Hoyle, Doran and Berry. The firm exists today known as HDB/ Cram and Ferguson). The November 1979 edition of LIFE magazine featured St. John the Divine Cathedral. To quote the magazine: (p.102) One architect from Cram's firm survives. At 80, John Doran is among the last architects able to draw gothic plans - the difficult style is not taught in schools. He is helping St. John's new generation of builders. "Nothing I've done," Doran says, "Has held my interest like the cathedral. Everything since then has just been making a living." Construction on the towers continued in fits and starts until the early 1990s, when a lack of funds forced its abandonment, the Cathedral having largely spent its endowment. Unused - and largely rusted - scaffolding had been covering the south tower until the summer of 2007, when workers began removing it. Apparently, some sections of the tower itself were removed in the process, as the tower appears shorter and gaps have appeared in its upper section. Under master stone carvers Simon Verity and Jean Claude Marchionni, work on the statuary of the central portal of the Cathedral's western façade was completed in 1997. The Cathedral has since seen no further construction, and the new generation of trained stonecarvers has gone on to other projects. Description of the cathedral The building as it appears today conforms primarily to a second design campaign from the prolific Gothic Revival architect Ralph Adams Cram of the Boston firm Cram, Goodhue, and Ferguson. Without slavishly copying any one historical model, and without compromising its authentic stone-on-stone construction by using modern steel girders, Saint John the Divine is a refined exercise in the 13th century High Gothic style of northern France. The Cathedral is almost exactly two football fields in length (601 feet or 186 meters) and the nave ceiling reaches 124 feet (37.7 meters) high. It is the longest Gothic nave in the world, at 230 feet. Seven chapels radiating from the ambulatory behind the choir are each in a distinctive nationalistic style, some of them borrowing from outside the gothic vocabulary. Known as the "Chapels of the Tongues" (Ansgar, Boniface, Columba, Savior, Martin, Ambrose and James), their designs are meant to represent each of the seven most prominent ethnic groups to first immigrate to New York City upon the opening of Ellis Island in 1892 (the same year the Cathedral began construction). In the center, just beyond the crossing, is the large, raised High Altar, behind which is a wrought iron enclosure containing the Gothic style tomb of the man who originally conceived and founded the cathedral, The Right Reverend Horatio Potter, D.D., LL.D., D.C.L., Bishop of New York. Later Episcopalian bishops of New York, and other notables of the church, are entombed in side chapels. Directly below this is a large hall in the basement, used regularly to feed the poor and homeless, and for meetings, and multiple crypts. On the grounds of the Cathedral, toward the south, are several buildings (including a Synod Hall and the Cathedral school), as well as a large bronze work of public art by the Cathedral's sculptor-in-residence, Greg Wyatt, known as the Peace Fountain, which has been both strongly praised and strongly criticized. On the night of December 18, 2001, a fire swept through the unfinished north transept, destroying the gift shop and for a time threatening the sanctuary of the cathedral itself. It temporarily silenced the Aeolian-Skinner pipe organ. Although the organ was not damaged, its pipe chambers had to be removed and laboriously cleaned, to prevent damage from the fire's accumulated soot. Valuable tapestries and other items in the cathedral were damaged by the smoke. In 2003, the Cathedral was designated a landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, however, shortly thereafter the designation was unanimously overturned by the New York City Council, which favored landmark status for the cathedral entire grounds, rather than just the building. However, no move to designate the entire grounds has formed. Thus, the cathedral is not officially a New York City landmark at this time. In January 2005, the Cathedral began a massive restoration that will remain in progress until June 2008. A state-of-the-art chemical-based cleaning system is being utilized, primarily to remove smoke damage resulting from the 2001 fire. The Cathedral houses one of the nation's premiere textile conservation laboratories to conserve the Cathedral's textiles, including works designed by Raphael. The Laboratory also conserves tapestries, needlepoint, upholstery, costumes, and other textiles for its clients. In early November 2006, vandals beheaded a statue of George Washington near the high altar of the Cathedral and left a dollar bill with George Washington cut out on what was left of the neck[1]. Activities at the cathedral The cathedral is a major center for musical performances in New York. Paul Winter has given many concerts there. Deans William Mercer Grosvenor 1911-1916 Howard Chandler Robbins 1917-1929 Milo Hudson Gates 1930-1939 James Pernette DeWolfe 1940-1942 James Albert Pike 1952-1958 John Vernon Butler 1960-1966 James Parks Morton 1972-1997 Harry Houghton Pritchett Jr 1997-2001 James August Kowalski 2002- |

|

|

The Cathedral of Saint John the Divine was a product of the Episcopalian Diocese's aspirations for the revival of urban life through the construction of a new institutional "Acropolis" atop Morningside Heights. The Episcopalian church also built the cathedral to compete with the city's Catholic constituency and their recently built St. Patrick's Cathedral. Still unfinished today, the project was initiated by Bishop Henry Codman Potter in 1872. In 1887 the congregation acquired a difficult site on the promontory at 112th Street, chosen for its prominence and view. Early debates over the building's style led to a competition in 1888 that was won by the young firm of Heins and Lafarge. Beginning in a Byzantine/Romanesque style at the Eastern choir end of the Cathedral, the architects shifted towards a more traditionally Episcopalian style, the English Gothic, during its construction. This stylistic variety, further complicated by the French Gothic mode of Cram and Ferguson's later work on the nave and Western facade, is similar to that found in Medieval churches. It endows the Cathedral with a sense of authenticity although it is a modern structure. The building rests on a Guastavino vaulted crypt. Inside, 100-foot composite piers support the ribbed groin vaults of the 600-foot long nave and side aisles. Built without the support of a steel frame, this structure is the largest load-bearing wall cathedral in the world. Heins and Lafarge's work meets Cram and Fergusons portion at the unfinished Guastavino vaulted crossing, whose southern transept is the Greek Revival shell of the 1840 Leake and Watts Orphanage. Suspended during World War II, construction recommenced on the unfinished Cathedral in 1979 under the supervision of the British stonemason James Bambridge. In keeping with the Cathedral's contemporary role as a social institution, the work took the form of a community development project. Local residents, trained in the traditional art of the masonry, became highly skilled artisans who could apply their specialized knowledge to work on the Cathedral, or on other buildings in the city. It is estimated that work on the Cathedral will take another one hundred years. Streetscapes/The Cathedral of St. John

the Divine, Amsterdam Avenue Between 110th and 113th Streets;

Much-Changed Century-Old Vision, Still Unfinished |

|

|

June 17, 2003 Landmark? Just Wait Till It's Finished By DAVID W. DUNLAP The Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine is expected to be declared a landmark on Tuesday. The news for most New Yorkers will probably be that as this day began, the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine was not a landmark. Then again, given a pace of construction almost as medieval as the architecture — 111 years and counting — it seems safe to say that it will be a century or two before they put the finishing touches on the vast cathedral. By day's end, however, the Landmarks Preservation Commission is expected to confer landmark status on a substantially unfinished structure for the first time, in an arrangement that would allow new buildings on the grounds, a prospect that worries neighbors and preservationists. The commission will continue to consider but not yet designate other historical structures in the cathedral compound, bordered by Amsterdam Avenue and Morningside Drive, Cathedral Parkway and 113th Street. Even three-fifths complete, the commission said, St. John the Divine is the largest church in the nation and the largest cathedral in the world. (The largest church in the world is the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace in Yamoussoukro, Ivory Coast, which is not a cathedral.) Only the exterior of St. John the Divine, the seat of the Episcopal bishop of New York, is to be considered as a landmark. By law, the commission cannot designate the interior of a religious sanctuary, even one that offers an experience akin to being in a dim and profoundly mysterious grove of Gothic sequoias. Robert B. Tierney, the chairman of the commission, said yesterday that the designation would culminate the panel's "37-year quest to landmark the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, a building with a unique place in the architectural, social and cultural history of the city and the nation." Should the cathedral trustees ever find themselves with enough money to resume construction, they would not necessarily be compelled to follow the existing French Gothic plans by Ralph Adams Cram, Mr. Tierney said. But he dismissed as "too speculative" the question of whether the commission might one day approve a departure as radical as the glass-enclosed biosphere designed a decade ago by Santiago Calatrava to complete the cathedral's south arm, or transept. Until recently, the cathedral's leaders had opposed landmark status. But last year, they agreed to cooperate with a designation that would preserve development potential at the north end and southeast corner of the grounds. The cathedral trustees are negotiating with Columbia University to build on those sites. Designs would be reviewed by a committee that includes two members appointed by the landmarks chairman. New buildings would also be governed by legal controls on their placement, height, shape and bulk. These controls would be "very protective of the cathedral" and other existing buildings "but nonetheless allow for development at a sufficient scale to support the cathedral's mission," Robert S. Davis of Bryan Cave, the law firm that represents the cathedral, said yesterday. "And a very important part of the cathedral's mission," he said, "is the maintenance, preservation and restoration of its historic buildings." Many preservationists had hoped the commission would designate the entire grounds, known as the Close. "It was all built as various parts of a larger whole, and the whole should be preserved," said Simeon Bankoff, executive director of the Historic Districts Council. "That just seems like rational preservation planning to me." Among the notable structures on the Close are the Synod House, the Diocesan House, the Cathedral School and the 160-year-old Town Building, designed by Ithiel Town as part of the Leake & Watts Orphan Asylum, which preceded the cathedral on the land. "The Cathedral of St. John the Divine is considered the crowning glory of the Morningside Heights neighborhood, which came to be known as `the Acropolis of the new world,' " reads a draft version of the landmark designation. The cornerstone was laid in 1892 for a Romanesque-Gothic cathedral designed by Heins & LaFarge. In 1911, the trustees brought in Cram, America's foremost advocate of Gothic architecture, to finish the job. Still under construction, the 601-foot-long cathedral was far enough along to be dedicated on Nov. 30, 1941. But work stopped abruptly a week later, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and did not begin again until 1979. The south tower then began to rise toward its intended 300-foot height as journeymen from England trained local residents as stonecutters. But after it reached 200 feet, the money ran out. A fire on Dec. 18, 2001, destroyed the gift shop, damaged the north transept and ravaged two tapestries. It seemed a crippling blow for a city staggered by the destruction of the World Trade Center. But the cathedral managed to reopen — the smell of smoke still in the air — in time for a Christmas Eve service. Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company ------------------------------ June 27, 2003 Big Buildings Planned on Grounds of St. John the Divine By DAVID W. DUNLAP The next crane you see on the grounds of St. John the Divine will not be there to complete the cathedral. Instead, large new buildings are planned on each end of the 11.3-acre grounds in Morningside Heights, under a development framework agreed on last week by the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine and the city's Landmarks Preservation Commission. The developer will probably be Columbia University. The agreement coincided with the designation of the Episcopal cathedral as an official landmark. It establishes three-dimensional bulk controls, called envelopes, within which construction can occur without further approval by the commission, although the panel will have two representatives on an 11-member design review board. Roughly two-thirds of each envelope could be filled with a structure. One building, overlooking Morningside Park, might be 20 stories tall, rivaling the nearby 424 Cathedral Parkway tower. The volumes suggest buildings that would have a total of nearly 700,000 square feet of floor area, though the amount could be much less, depending in part on whether the buildings are residential or institutional. Even 700,000 square feet falls far short of the theoretical zoning potential for the entire site. But the prospect of new structures on the cathedral grounds, known as the Close, has sounded alarms. "Let's try to imagine the French allowing a building that would block views of Notre Dame," said Joyce Hackett, a novelist and the president of Morningside Heights Neighbors, a community group. According to the agreement, the cathedral will use substantially all of the proceeds from the development to "restore its operations to a sound financial footing," increase its endowment (now $7 million) and "maintain, preserve and restore the cathedral building and other historic buildings." Deferred maintenance and site improvement projects require $17 million to $20 million, said Stephen Facey, the executive vice president of the cathedral. Getting the cathedral back on its feet would set the stage for a capital campaign to finish the structure, which was begun 111 years ago. But Ms. Hackett asked, "To what length can nonprofits go to fulfill their mission?" Besides generating revenue, which cathedral leaders would not estimate, development must be "congruent with the cathedral's mission and vision" and "compatible with the cathedral's historic architectural qualities," the trustees have said. They also said they expected architecture that was "not necessarily conventional," offering as examples the work of Diller & Scofidio, Steven Holl, Rafael Moneo and Renzo Piano. The envelopes do not dictate shapes but rather maximum dimensions. No more than 68 percent of the north envelope and 65 percent of the southeast envelope can be occupied by a building. The north site has a height limit of 146 feet, equivalent to the point where the cathedral roof line begins, said Michael Kwartler of the Environmental Simulation Center, planning and zoning consultants to the cathedral. The southeast site has a two-tiered height limit of 160 and 200 feet above the level of the cathedral grounds. Because it occupies a promontory, it would rise up to 235 feet above Morningside Drive. A parking lot and the former Cathedral Stoneworks fill the north site. The rose garden and playground on the southeast site would be relocated, Mr. Facey said. Significant views of the cathedral would be preserved by the alignment of the envelopes, Mr. Kwartler said, including those along Amsterdam Avenue, down Morningside Drive and across Morningside Park. Robert B. Tierney, chairman of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, said that the anticipated construction "would in no way detract from the cathedral" and that by allowing development, "we can be assured that the landmark will be protected in perpetuity." But Carolyn C. Kent of the Morningside Heights Historic District Committee, a neighborhood preservation group, called the landmarks commission "actively complicit in this destructive spoiling." "It would," she said, "visibly inflict on holy ground this new American century's apparent readiness to disrespect and spoil for profit our finest sites of art and architecture." Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company ---------------------- October 23, 2003 Council Threatening to Block Cathedral's Landmark Status By DENNY LEE City Council officials say they are poised to reject the landmark status granted to the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, hoping to prevent the construction of large new buildings on the grounds surrounding the church, a 111-year-old Gothic structure in Morningside Heights. Should the Council take the action in a meeting scheduled for tomorrow, it would be only the third time that it has invoked its power to overturn a landmarks designation. At issue is not whether the cathedral is worthy of landmark designation. Rather, many Council members are objecting to an agreement between cathedral officials and the Landmarks Preservation Commission that would allow for the large new buildings to be erected on the 11.3-acre grounds that flank the cathedral. Columbia University hopes to develop the sites, and has already commissioned Polshek Partnership Architects to draft designs. Preservationists contend that the agreement, which would allow for towers as tall as 20 stories, would trample on hallowed grounds and sully the majestic views of the cathedral. "I will not support the landmark commission's recommendation to merely landmark the cathedral," said Councilman Bill Perkins, who represents Morningside Heights and is a member the Council's landmarks subcommittee. He said any landmark designation should include the grounds as well. Under the city's administrative code, the Council has until tomorrow — 120 days after the landmarks commission issued its designation — to vote on St. John the Divine. If it fails to act, the designation is approved by default. A vote rejecting the designation, however, does not prevent the cathedral from pursuing its development plans. It merely maintains the status quo, which, in this case, means that neither the cathedral nor its surrounding grounds are protected by the city's landmark laws. Although there is no danger that anyone would alter the cathedral, the landmarks commission has long believed that failure to designate it a landmark has been a glaring omission. The scheduled vote has unleashed a flurry of lobbying efforts on both sides. Former Mayor David N. Dinkins, who is currently a professor at Columbia, has called Council members on behalf of the cathedral, saying it needs money from the development sites to shore up its ailing finances. "The cathedral is really undercapitalized," said Robert S. Davis, a partner in Bryan Cave, one of the law firms representing the cathedral. "There is deferred maintenance of about $20 million that the cathedral isn't able to afford. The roof leaks." Council Speaker Gifford Miller has told several colleagues that he is opposed to the designation. Mr. Perkins, joined by local preservationist groups, has contended that the proposed designation would set a precedent for future developers to chip away at potential landmarks. "This is akin to building a neo-Classical addition to the Seagram building," said Michael Adams, an architectural historian of Harlem, referring to the modernist icon on Park Avenue. "The cathedral is inviting money lenders into the temple." Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company -------------------------- October 25, 2003 No Landmark Status for St. John the Divine By WINNIE HU The Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine has punctuated the New York skyline for more than a century, but its designation as an official city landmark was rejected yesterday by the City Council. Council members, as expected, voted unanimously against landmark designation for the 111-year-old Gothic structure in Morningside Heights. This came after Bill Perkins, who represents the area, and other council members argued, essentially in an all-or-nothing approach, that the protective status should also be extended to the cathedral's 11.3-acre grounds to control development there. "It was a declarative statement that St. John the Divine should be landmarked in totality, not piecemeal," Mr. Perkins said. "It is, quite frankly, an insult to the historical value of this world-renowned church to have it piecemeal like this." In June, the Landmarks Preservation Commission had designated the cathedral as a landmark as part of an agreement with cathedral officials that would also allow the development of two sites on its grounds for new buildings. Under the city's administrative code, the council had until yesterday to reject that designation; otherwise, it would have been approved by default. The council's action, however, does not prevent cathedral officials from pursuing development plans for its grounds. It does mean that the cathedral remains unprotected by the city's landmark laws. Cathedral officials have historically opposed landmark status for the cathedral and its grounds, arguing that such a designation would hinder their efforts to complete the long unfinished structure. In recent years, though, they have agreed to a designation for the cathedral and the land immediately underneath it. But cathedral officials have continued to oppose landmark designation for the grounds. Last November, they announced plans to lease part of the property to Columbia University for development as a way to bring revenue into the financially troubled cathedral. Cathedral officials expressed disappointment yesterday in the Council's action, but said it would not change their plans. "We intend to proceed with our ongoing discussions with Columbia University with respect to the development of two sites on the periphery of the cathedral grounds," said the Very Rev. Dr. James A. Kowalski, dean of the cathedral. Mr. Perkins said that while he sympathized with the cathedral's financial problems, he would call on the landmarks commission to designate the entire property as a landmark as soon as possible. Robert B. Tierney, chairman of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, said that he believed the commission had struck a "reasonable, sensible balance" between preservation and the needs of the cathedral. Copyright 2003 The New York Times Company ------------------------------------- December 9, 2004 |

|

|

links |

|