|

New York

Architecture Images-Lower East Side

St. Mark’s in the Bowery Church (Episc.) |

|||||

|

architect |

Ithiel Town | |||||

|

location |

East 10th St. at Second Ave. | |||||

|

date |

Built/Founded: 1799, restored 1975-1978, restored 1978-1984 | |||||

|

style |

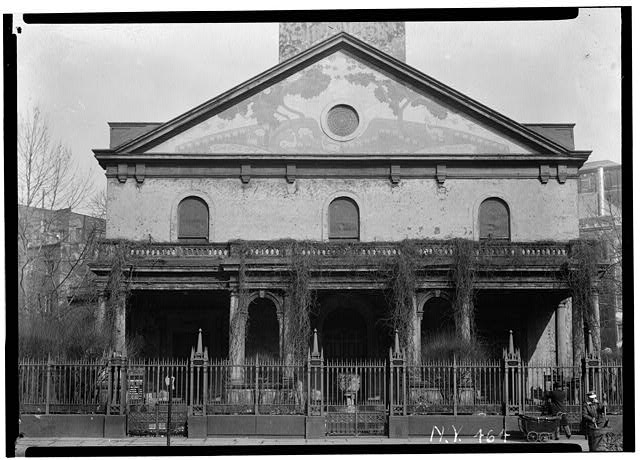

Greek Revival steeple added 1828 and an Italianate portico completing the structure in 1854. | |||||

|

construction |

stone | |||||

|

type |

Church | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

.jpg) .jpg) |

||||||

| Aspiration statue | ||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

Special thanks

to www.churchcrawler.co.uk

(British and international church architecture site) for above image. |

||||||

|

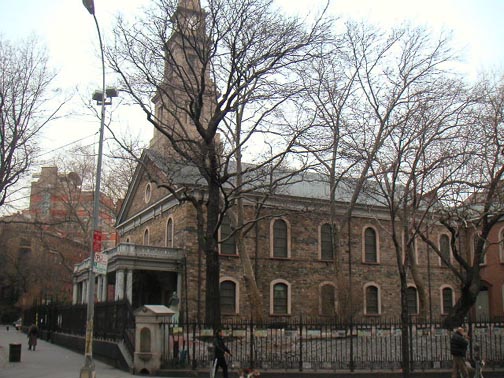

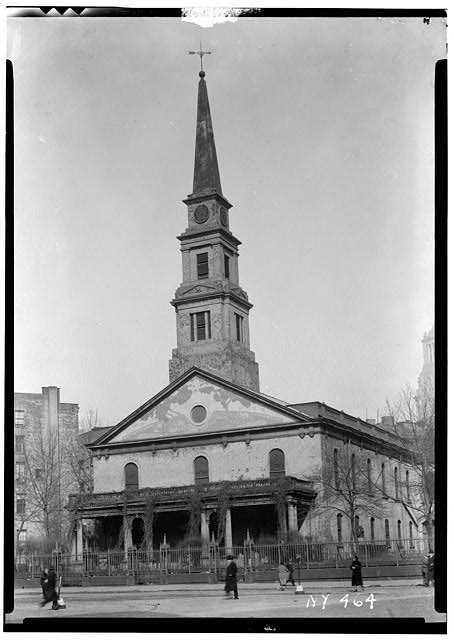

St. Mark's Church, 2007St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery, at 131 East 10th

Street, is located at the intersection of 10th and Stuyvesant Streets

and 2nd Avenue in the East Village in New York City. History and architecture In 1651, Peter Stuyvesant, Governor of New Amsterdam, purchased land for a bowery or farm from the Dutch West India Company and by 1660 built a family chapel at the present day site of St. Marks Church. Stuyvesant died in 1678 and was interred in a vault under the chapel. Stuyvesant's great-grandson, Petrus, would donate the chapel property to Episcopal Church in 1793, stipulating that a new chapel be erected and in 1795 the cornerstone of the present day St. Mark's Church was laid. The church was completed and consecrated in 1799. Alexander Hamilton would then provide legal aid in incorporating St. Mark's Church as the first Episcopal Parish independent of Trinity Church in the new world. In 1828, the church steeple, designed by Martin E. Thomson and Ithiel Towne is erected. Soon after the two-story fieldstone Sunday School is completed. In 1838, St. Mark's Church establishes the Parish Infant School for poor children. Later, in 1861, St Mark's Church commissioned a brick addition, designed and supervised by architect James Renwick, Jr. and the St. Mark's Hospital Association is organized by members of St. Mark's. And at the start of the 20th century, leading architect Ernest Flagg designed the rectory. While the 19th century saw St Mark's Church grow through its many construction projects the 20th century would be marked by community service and cultural expansion. Several Dutch dignitaries made stops by the church on their visit to the states. In 1952, Queen Juliana of the Netherlands would visit the church and lay a wreath given by her mother, Queen Wilhelmina, at the bust of Peter Stuyvesant. And later, in 1981 and 1982, Princess Margriet and Queen Beatrix, both of the Netherlands would visit. In 1966, The Poetry Project and The Film Project (later to become the Millennium Film Workshop), were founded. And in 1975, The Danspace Project is founded by Larry Fagin; the Community Documentation Workshop under the direction of Arthur Tobler is established; and the Preservation Youth Project expands to a full-time Work Training Program and under the supervision of artisan teachers undertakes mission of the preserving St Mark's landmark exterior. On July 27, 1978, a fire nearly destroyed St. Mark's Church. The Citizens to Save St Mark's was founded to raise funds for its reconstruction and the Preservation Youth Project undertakes the reconstruction supervised by architects Harold Edleman and craftspeople provided by preservation contractor I. Maas & Sons. The Landmark Fund emerged from the Citizens to Save St Mark's and continues to exist to help maintain and preserve St. Mark's Church for future generations. Restoration finished in 1986. Services St. Mark's Church is a very active parish church, holding services, concerts, and occasional lectures. The church services include a long established Hispanic ministry and more recently a Japanese ministry. Staff Reverend John E. Denaro, Priest-in-Charge Reverend Michael Relyea, Associate Pastors Reverend Frank Morales, Associate Pastors St Mark's and the arts St. Mark's also hosts modern artistic endeavors, The Poetry Project, Danspace Project holding events year round. Richard Foreman's avant-garde theater, Ontological-Hysteric Theater, is also housed there. Famous congregants Gideon Lee, Vestryman and Treasurer of St. Mark's Church as well as Mayor of New York City Notable burials Daniel D. Tompkins, Vice President of the U.S. under President James Monroe and former Governor of New York Alexander Turney Stewart, the wealthy New York merchant, is buried in 1876. Three weeks later his body is stolen and held for ransom. Miscellanea Gideon Lee, Vestryman and Treasurer of St. Mark's Church, is elected Mayor of New York City in 1832. 1860 The Ladies' Benevolent Society is formed by women of St. Mark's Church. American architect, Frank Lloyd Wright presents plans to build two high-rise towers on St. Mark's grounds in 1929. In 1940, St. Mark's Church becomes a branch of Bundles for Britain, Inc. Shortly after the 1996 murder of Abe Lebewohl, owner of the famous Jewish Deli, 2nd Avenue Deli across the street, the two triangle gardens in front of the church were renamed in his honor. During the 2004 Republican National Convention, hosted in New York City, St Mark's Church hosted the National Anarchist Movement by allowing the young members to erect a temporary encampment on its grounds. References ^ "AIA Guide to New York City, 4th Edition, pg 173 |

||||||

Saint Mark's, established in 1799, is the

final resting place of Peter Stuyvesant, the last Dutch governor of New

Netherland. Services are Sun 9:30am Lectio Divina (Bible study) and Sun

10:30am General Worship Service.

St Marks-in-the-Bowery"The Bowery" was Dutch governor Peter Stuyvesant's farm, and his private chapel used to stand on this site--making this the oldest site of continuous worship in Manhattan. This church was erected 1795-99-- one of the few surviving 18th Century structures in Manhattan--with a Greek revival steeple added 1828 and an Italianate portico completing the structure in 1854.Originally a church of Manhattan's elite, St Marks became a progressive force in the neighborhood both socially and culturally. Supportive of immigrant, labor and civil rights, the church was a meetingplace for Black Panthers and Young Lords, and launched the first lesbian healthcare clinic. Poets like W.H. Auden (who was a parishoner), William Carlos Williams, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Amy Lowell, Carl Sandburg, Kahlil Gibran, Allen Ginsberg, Patti Smith and Jim Carroll have all read here; since 1966, the St Marks Poetry Project has organized poetry events. The Danspace project has featured dance legends like Isadora Duncan, Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham. Sam Shepherd's first two plays were produced here, and Andy Warhol screened his early films. St Marks ChurchyardFamous residents include former governor and vice president Daniel Tompkins, who abolished slavery in New York; Commodore Perry Matthew Perry, who forced Japan to accept U.S. trade; and New York Mayor Philip Hone. Peter Stuyvesant himself is buried under the church, and six generations of his descendants are also found here.Department store pioneer A.T. Stewart, whose store filled the block between 9th and 10th streets east of Broadway, was buried here in 1876, but on November 6, 1878, his body was snatched and held for $200,000 ransom. The widow eventually regained possession of the corpse in 1881, after bargaining the kidnappers down to $20,000. He now rests elsewhere. St Marks West YardWest Yard; the space between St Marks' rectory and the church was to be filled in by a 18-story apartment tower designed by Frank Lloyd Wright; with all due respect to Wright, it's a blessing that the Great Depression scuttled the plan. Some of the ancient maples in the yard were lost to the Asian Longhorn Beetle in 2000. |

||||||

| The following reprinted with the generous permission of David Bank. | ||||||

|

My Neighborhood: The emergence of diversity on Stuyvesant’s land. David A Bank, April 19 2002.

Writing about my neighborhood requires me to define a

neighborhood.

I live on the northeast corner of

Peter Stuyvesant was the Director General of the entire colony of

Of course, this land is no longer Stuyvesant’s farm, but one crucial

remnant still exists today, albeit in another form.

In 1678, Stuyvesant was buried in a vault below his private chapel.

Over a century later, in 1793, his great-grandson Petrus donated

the chapel land to the Episcopal Church to build a new chapel called

Saint Mark's Church in-the-Bowery1

(Saint Mark’s Church website).

It is a remarkable irony that Petrus remembered his great-grandfather

Peter by establishing an Episcopal Church on his burial site.

Yet, during his life, Peter prohibited the practice of any belief

other than Dutch Reformed.

How could Peter’s own great-grandson be a prominent Episcopalian?

The Episcopalian church has its roots in the Church of England.

It had tradition and prestige, and by the end of the eighteenth

century, any New Yorker who had money and wanted to show it off needed

to be an Episcopalian.

Despite all his efforts, it seems that this is one clear example of

Peter’s failure in his attempt to prevent diversity in

Nevertheless, St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery, a beautiful, yet somewhat

plain looking Georgian style church was finished in 1799 and still

exists today on the northwest corner of

The church has since been through a number of additions.

It is interesting that in 1861, the date Renwick completed these row

houses; he had already completed Grace Church and was in the process of

building St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

Renwick was also a wealthy Episcopalian.

His mother’s family, the Brevoorts, had owned the land on which Grace

Church was built. To me,

the prestige of the archtiect strongly suggests that Renwick’s Italian

style row houses, which today form part of the landmarked historic

district, were built as the most luxurious of homes for

On the west side of St. Mark's is the church’s infamous graveyard,

beneath which Stuyvesant was originally buried.

The graveyard was the site of one of

Another interesting anecdote about St. Marks is that Frank Lloyd Wright

designed three apartment towers to fit behind the church.

However, due to the Great Depression, his buildings were never

built (Morrone, 98). Even

though Wright’s plan never succeeded, the Church that stands today is

unfortunately not the same as it was upon completion in 1854.

Rather it has been largely restored after a devastating fire in

July 1978, in which the building’s roof collapsed (Wolfe, 24).

Petrus Stuyvesant did not only donate the land for St. Mark’s Church,

but he also built the nearby Federal style brick house that stands on

the north side of

This red brick building has very little ornamentation aside from the

Corinthian pilasters, the dentals at the roof, and the large rounded

arches.

It is difficult to determine a style for this building though its

heavy walls and round arch may suggest the German round-arch style.

Rentz's design created a building that revolutionized nightlife, as

it became the first modern nightclub.

“During prohibition, the balls moved from the social and political trends

of the past to the hedonistic attitude of the ‘speak’"(Webster Hall NYC

website). Yet, the police

did not interfere as Al Capone was rumored to be the owner.

In the 1950’s R.C.A. took over the building and used it as a

recording venue. In the

1980s, Webster Hall, now called the Ritz, became famous as “the best

stage in

While Webster Hall brought bohemian life to my neighborhood, my next

building was a part of a different form of entertainment, which took

place amongst a thriving Eastern European Jewish population.

In the 17th century, Stuyvesant would not let Jews into

his colony, however he was ultimately unsuccessful.

This failure began in 1654, when twenty-three Jewish refugees from

In 1892, the first Yiddish Theatre was established.

This was the beginning of a vibrant theatre district on

“Yiddish theatre was an important community institution: plays offered

entertainment and escape, portrayals of immigrant life, and political

forums” (Sandrow, 1282).

However, after the First World War, immigration restrictions weakened

Yiddish Theatre by greatly decreasing the influx of Yiddish speaking

people.

Later, with World War II, much of the Yiddish speaking population

in

Yiddish theatre passed its prime and many Jews moved to more wealthy

neighborhoods of the city.

So what happened to my neighborhood?

It seems that as time passed, Stuyvesant’s personal land has grown

farther and farther away from Peter’s goal of an exclusively white,

Dutch Reformed population.

In fact, in the 1960s intellectuals, artists, musicians and writers from

The future of my neighborhood was also largely influenced by

In 1985, N.Y.U. decided to do something about this problem by building

two new dormitories on the empty plots located at

By the summer, N.Y.U. had selected a design and planned to continue with

construction. In July, a

second major protest led to the arrest of nineteen people for

trespassing onto the construction site.

“The police used bolt cutters to remove four people who had chained

themselves to a building crane”, while others were “accused of throwing

a paint bomb that hit a police officer and of putting dirt in the gas

tanks of construction equipment” (“19 Arrested”, sec. 1, p. 25).

Despite all opposition, N.Y.U. was able to build

Alumni Residence Hall5

on

Alumni Residence Hall was built sixteen stories high, yet Voorsanger

attempted to contextualize it with the historic district on

Voorsanger built Third North, the building in which I live, as three

connected fourteen-story towers with a central courtyard and a dining

hall.

The bedrooms are shared by two students and the suites each have a

small kitchen, living room and bathroom.

The courtyard allows all suites to have windows, facing either the

courtyard or the street, thereby creating natural light within the

rooms.

The building currently houses just fewer than one thousand students

and charges close to ten thousand dollars each school year.

It is extremely important that N.Y.U. was able to build such large

buildings through a zoning technicality.

The zoning laws in my neighborhood in 1985, indicated that “a C6-1 zone

permits a floor area ratio, or FAR, of 6 (6 square feet of building for

each square foot of land) when the use of the land is commercial, but

only 3.4 when it is residential” (Oser, sec. A, p. 32).

“Since the university dormitories are considered a community

facility, N.Y.U. was able to utilize the 6 FAR on the Avenue, and

therefore was a logical purchaser of the site” (32).

It seems strange that my building can be considered a community

facility. After all, in

order to enter my own building, I require identification indicating my

residence or I must pass through a hand scanning machine.

These two buildings were the start of N.Y.U.’s massive effort to provide

housing for all students.

This was one crucial element of the school’s improvement over the past

seventeen years. Today,

N.Y.U. is an exclusive, first-rate private university that is beginning

to compete with the older, more prestigious Ivy League schools.

However, these two dormitories did not only change the face of a

school, they have also revitalized my neighborhood.

Today, both Alumni Hall and Third North have small commercial

stores at street level and the neighborhood is filled with bars, clubs,

coffee houses and restaurants often frequented by students.

N.Y.U., “the top American undergraduate university for

international students,” is the home and campus to thousands of young

students of different race, religion and nationality, many of whom live

on the

Today, my neighborhood is youthful and vibrant largely because of the

N.Y.U. students who live here.

However, three hundred and fifty years ago, this land was the manor

house and chapel of Peter Stuyvesant’s farm.

There are probably more people living in my building alone than

Stuyvesant could have ever imagined might live on his land.

When I think of my neighborhood, I realize how drastically it has

changed.

It began as the farm of one man and then with the construction of

St. Mark’s Tiny Stuyvesant Street, crossing E. 9th Street between 3rd and 2nd Avenues, is notable for being the one and only diagonal street in Manhattan north of 8th Street and south of Central Park except Broadway. (We'll leave Greenwich Village out of it, since it's always had its very own street system quite independent of the gridiron imposed by the Commissioners' Plan (Randel Survey) back in 1811.) As in most exceptions to the rule, it has its own story to tell!

Where St. Mark's now stands, the Second Dutch Reformed Church, of which Peter Stuyvesant was a parishioner, stood in the 1600s. His family vault was placed near that church and remains today besides St. Mark's. Petrus Stuyvesant, Peter Stuyvesant's great-great-grandson, owned most of the land in this area and his mansion, called Petersfield, was located in the block between 1st Avenue, Avenue A, and East 15th and 16th Streets. It was Petrus Stuyvesant who laid out a street system and donated land and construction funds for St. Mark's, which was completed in 1799. The area around Petersfield, extending west to the old property line at the Bowery Road, became known as Bowery Village in the early years of the 19th Century. Because Bowery

Village lay just outside

the city limits, farmers could sell there without paying a market tax.

Wagon stands soon flourished along 6th and 7th Streets, along with a

weigh scale for Westchester hay merchants. Comfortable residences went

up along the upper Bowery (Road), still a country road edged with

blackberry bushes...Artisan house-and-shops arrived too; so did

groggeries, a brothel, and a post office (in truth an oyster house where

the postrider left mail for the village). From 1804 the community even

had its own (short-lived) newspaper, the Bowery Republican. As New York City expanded ever northward as the 19th Century rolled on, Bowery Village was incorporated and most signs of it, with the exception of St. Marks-in-the-Bowery, gradually disappeared. But Stuyvesant Street had by then become a well-established thoroughfare and so was allowed to remain after the Commissioners Plan has eliminated most of the other odd roads that would have interrupted the grid. (For example, Petersfield Street, which extended from the Bowery Road at about 11th Street to the Petersfield mansion, was eliminated when the cross streets of today were cut through.)

|

||||||

|

links |

||||||