|

October 20, 2002

Fading Into History

By ALLEN SALKIN

"Lower East Side" (1900), collection of Lisa Ades, Jewish Museum

LINDA Macfarlane, née Feuer, stood on East Houston Street and looked

stunned as she peered south at the sleek bistros and boutiques lining

Orchard Street. "It's all gone," she whispered to her husband as she

clutched his arm. "What happened?"

Ms. Macfarlane, 59, left New York more than 25 years ago. Now, on a recent

visit to the city, she wanted to show her husband the children's

clothing store where she had worked "selling shmattes" as a teenager.

But the store, whose name she cannot remember, is gone, as are most of

the landmarks and talismans in the neighborhood that was for generations

the traditional symbol of the American Jewish experience: the fabric

merchants, the ethnic food sellers, the children's furniture stores.

"I wanted to smell it, follow my nose, the food, the places," Ms.

Macfarlane said wistfully, brushing her blond hair back from her eyes.

"But nothing smells the same anymore. The people, everything's gone. The

whole ghetto is gone."

Last month, Ratner's Delicatessen on Delancey Street sold its last onion

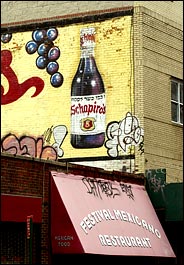

roll and closed after 97 years. Two years ago, the owners of Schapiro's

Kosher Winery on Rivington Street rolled their barrels out of the

basement and called it quits, selling the building for $2.3 million. Two

weeks ago, H&M Skullcap moved from its home on Hester Street, where

it had been for half a century, to 13th Avenue in Borough Park,

Brooklyn, a thriving Jewish business thoroughfare. "The Chinese don't

want to buy yarmulkes," said Mendel Fefer, a salesman. Some of the

remaining small synagogues have so few members that they must import

teenagers from Williamsburg, Brooklyn, to help make the minyan of 10

required for daily prayers.

The long-contracting Jewish Lower East Side, the primal homeland for

American immigrant Jews, has lost so much of its cultural texture and so

many of its living touchstones that it may be time finally to pronounce

it dead. Yet paradoxically, even as the traditional neighborhood

vanishes, interest in its place in Jewish heritage is exploding,

evidenced by the packs of competing walking tours, a spate of new books

about its history and increased attendance at the Lower East Side

Tenement Museum.

At its peak, around 1910, the square-mile area bounded by East Third

Street, the Bowery, Catherine Street and the East River was home to

373,057 people, a great majority of whom were Eastern European Jews. In

the 2000 census, the entire population was only 91,704, nearly half of

whom were of Asian descent. Only 17,200 were whites of non-Hispanic

descent.

Despite its changing ethnic and religious makeup, the Lower East Side is

hardly suffering economically. Shiny new shops, selling everything from

rubber miniskirts to $10 margaritas, have taken over storefronts and

brightened blocks that had been abandoned for decades. Clinton Street

has become a gourmet destination and Orchard Street a high-fashion

strand. The long-shuttered Sunshine Theater on East Houston Street, once

a Yiddish vaudeville house, is now a cinema. Moviegoers can fortify

themselves with refreshments from the venerable Yonah Schimmel Knishes

next door.

Grand Street between Allen and Chrystie Streets bustles with Chinese shops

selling vegetables and seafood. Last month, Vanity Fair magazine

published a map showing local outposts of trendiness.

Despite such shifts, for countless American Jews like Ms. Macfarlane, the

area has remained almost a holy land in memory, an old country to return

to. The real old country — the cities, towns and shtetls of Europe — has

long since disappeared in clouds of war and genocide. But even as

recently as a few years ago, a person walking the streets of the Lower

East Side could sense the collective memory of a tangible past, helped

along by the few Jewish businesses that survived.

Two years ago, the area was designated a state and national historic

district. But such a designation does not freeze a neighborhood's

appearance and retard change the way landmark designation does.

As a result, what is being lost now are the last images that make it

possible to conjure the fantasy of the old days. And a few tenements

where Jews once lived, a couple of silver candlestick sellers, Russ

& Daughters smoked-fish emporium and Streit's matzo factory are not

enough to do the trick for people like Ms. Macfarlane or any of the

other mystified visitors seen daily on Orchard Street. To make the dream

live, they seem to need the taste of kosher corned beef (Katz's

Delicatessen is not kosher), the reek of pickles in brine and the

Yiddish-inflected voices of haggling merchants.

They crave the specters of a vanished culture, said Joyce Mendelsohn, who

teaches New York City history at the New School and leads walking tours

based on her guidebook, "The Lower East Side Remembered and Revisited"

(Lower East Side Press, 2001). "People got upset when Ratner's closed,"

she said. "They feel an emotional, nostalgic tie to the neighborhood,

which is expressed in food in a large way. They are running for the

bialys, for the pickles. It's like the heart of the Jewish experience

they're hoping to go back to in some way."

Jewish or Not Jewish?

Some people say it is premature to announce the death of the Lower East

Side as a Jewish enclave. They point to the recent restoration of a

century-old mikvah (ritual bath) on East Broadway, the 270 children who

attend local yeshivas and the small synagogues that still dot the

streets. Kosher food is still available; Kossar's Bialys on Grand Street

sells 500 dozen bialys a day, 30 percent of them to retail customers and

the rest to stores like Zabar's.

William Rapfogel, executive director of the Metropolitan Council on Jewish

Poverty, says his organization's statistics show that the number of

Lower East Side Jews has not changed much over the past decade.

"It may not be as religious, but it's still Jewish," said Debra

Engelmeyer, 32, whose family bought Kossar's from the company's founding

family four years ago.

But the district is feeling the effects of both an aging population and

real estate shifts that have transformed much of the city. Cooperative

Village, for example, a 4,500-apartment complex south of the

Williamsburg Bridge built as housing for union members, was for decades

heavily Orthodox Jewish. Starting in 1997, when restrictions on the

selling price of apartments were lifted, many residents began taking

generous profits and leaving. A fourth of the units have been sold. The

management of the complex says young Orthodox families are moving in,

drawn by the opportunity to knock down walls and create large apartments

to house large families. But real estate brokers who have handled sales

at Cooperative Village say the new buyers represent many different

ethnicities.

Almost every night, Rabbi Schmuel Spiegel struggles to gather a minyan at

the First Roumanian-American Congregation on Rivington Street. One

recent evening, just before services were to start, Rabbi Spiegel had

only five men in his sanctuary. Hurrying out the door, he went to

Orchard Street.

"You coming to shul?" he asked Sam Weiss, who sat outside his men's shop.

"There's no one else to watch the store," Mr. Weiss replied.

The rabbi bounded into Altman's Luggage. "You're on your minyan roundup?"

asked Dan Bettinger, the shopkeeper. But he couldn't make it, either.

Rabbi Spiegel tried Dolce Vita Shoes, and even stuck his head into a car

parked on Rivington Street because the driver was wearing a yarmulke.

Ten minutes later, he only had eight men, including a tourist from San

Diego named Al Krinick who had shown up because he had heard "they were

still davening" in the synagogue where his grandfather had prayed more

than half a century before. A phone call to Katz Furniture on Essex

Street yielded a father-and-son pair. Mission accomplished.

"Twenty years ago, you would have said there will never be a minyan there

in 20 years," Rabbi Spiegel said later. "But we're still here. Ten years

from now, I can't say."

Mythmaking and the Museum

While the Lower East Side may not be what it was, in fact, the

neighborhood as remembered, idealized and enshrined in popular culture

probably never existed.

The story of life in those precincts is achingly familiar: immigrants

jammed into hellish tenements, entire families laboring long hours for

meager wages in equally hellish sweatshops, rampant and devastating

disease. Most Jewish immigrants wanted nothing more than to get out.

"If it were still a poor neighborhood of Jews selling cheap clothes and

other things and struggling to survive, it wouldn't be iconic, it would

be a problem," said Hasia R. Diner, a professor of American Jewish

history at New York University and the author of "Lower East Side

Memories: A Jewish Place in America" (Princeton University Press, 2000),

a work exploring why the neighborhood has been remembered fondly over

the years. "It's only with the moving on, with the passage of time, that

that sort of stuff can be viewed as sweet and lovely."

After World War II, and gaining urgency in the 1960's and 1970's with

books like Irving Howe's epic "World of Our Fathers," the Lower East

Side became an ever more powerful symbol of the bygone life of the

shtetl, where, as Ms. Diner put it, "families got along, neighbors took

care of each other and all the food tasted better."

That impulse is turning the Jewish Lower East Side into a museum piece.

Walking-tour guides point to where things used to be, not where they

are. The Forward building, home until 1974 of the Yiddish-language

newspaper that in the 1920's sold 250,000 copies a day, was converted

into expensive loft apartments. The Forsyth Street Synagogue is a

Spanish-language Seventh-day Adventist Church. The Garden Cafeteria,

where Isaac Bashevis Singer set his short story "The Cabalist of East

Broadway," is a Chinese restaurant.

"There is more of a future for tourism than there is for Judaism," said

Philip Schoenberg, who has led Jewish Lower East Side Talk and Walk

tours since 1992. "I have people who go on my tours, and all I'm saying

is: `This was once a kosher butcher shop. This was this. This was once

that.' "

In addition to the tours conducted by Mr. Schoenberg and Ms. Mendelsohn of

the New School, there are others led by the Tenement Museum (every

weekend) and Big Onion Walking Tours (which runs a Jewish Lower East

Side tour monthly). Ms. Mendelsohn, who books some of her tours through

the 92nd Street Y, has been hired by the Lower East Side Conservancy to

train docents for tours of historic Lower East Side synagogues. In the

last year, more than 12,000 people have taken these tours.

As flesh-and-blood Jews leave, mythmaking becomes ever more powerful.

In 2000, the patch of Orchard Street in front of the Tenement Museum was

torn up and replaced by perfectly even rows of unchipped black

cobblestone, to give a period feel. The museum, which opened in 1988,

takes visitors from around the world into tiny, historically restored

apartments at 97 Orchard Street, where 7,000 people lived between 1863

and the 1930's. Annual attendance has soared, from 18,000 in 1992 to

82,000 in the fiscal year ending June 30.

Since 1986, a $10 million restoration has been under way at the Eldridge

Street Synagogue. These days, the spectacular stained-glass window on

the facade is clear enough for sunlight to flow into the 115-year-old

sanctuary. But this space, where 1,000 people once worshiped on the High

Holy Days, still needs work. Saturday morning services are held in a

small basement room.

Changes, Even in Little Shtetl

If a Jewish equivalent to Little Italy remains in Manhattan — Little

Shtetl, say — it is probably the two-block stretch of Essex Street

between East Broadway and Grand Street, where half a dozen stores carry

signs with Hebrew lettering. Yet even here, tides of change are

apparent.

At No. 7, an 11-story luxury condominium is rising over neighboring

tenements. The sign promises "yards, roof terraces, fireplaces, skyline

views — 1,584 to 3,650 square feet from $825,000." At No. 11 Essex sits

the building that until a year ago housed A1, a store that sold Judaica.

Past a Chinese-run store selling cellphones and car parts, at No. 13, is

Motty Blumenthal's Judaica shop, named Z & A Kol Torah by his

parents, Zelig and Aliza, who opened it 50 years ago. "As long as people

come here, I'll stay," Mr. Blumenthal said. "It'll last at least another

5 or 10 years."

At No. 17, next door to Chinese North Dumpling, is Essex Electronics. For

many of the store's 35 years, the area was a major destination for

Israeli tourists seeking discounted stereo equipment. "There used to be

20 shops here," said Chaim Loeb, the manager. "Now there are three or

four, but some people still come."

Above another storefront at No. 17 is a friendly ghost: the sign

Ha-attikos Judaica. The shop closed years ago, neighbors say, and the

space is now an apartment.

At No. 19 is Weinfeld Skull Caps, which has been at the same location for

70 years. Recent customers included Martin and Goldie Sosnick, a San

Francisco couple who were ordering 240 black suede yarmulkes for their

daughter's wedding. "It's nice to come to where the roots are from," Ms.

Sosnick said. But, she added, "it was disappointing to come here wanting

to eat in a kosher restaurant, and there wasn't one here."

Soon Weinfeld's will be gone, too; one of the owners said he planned to

move the business to Brooklyn within the year, "to be in a Jewish

neighborhood."

No. 21 houses T & H Insurance, which has a Chinese-lettered sign, and,

until two months ago, Israel Wholesale Import, a Judaica shop, which

jumped to 23 Essex, displacing a Chinese printer. Also at No. 23 is

Hollywood Video, which sells Chinese-language videos; the sign

identifies the address as "23 Exsses St." And so it goes.

Qun Lei, a clerk at Shun Da Sign, a store at 25 Essex Street that

manufactures many of the Chinese-language signs that are installed when

the Hebrew signs come down, sees the block's future more clearly than

its past. "I think it's a Chinese neighborhood," said Ms. Lei, 33, who

emigrated from China a year ago and calls herself Maggie."

Ms. Lei hopes to save enough money so she and her family can leave the

neighborhood, unconsciously following the path trod by Jews of nearly a

century ago. "Uptown Manhattan is good," she said.

Looking at a Cloudy Future

Not every business that might speak to the real or imagined past is gone.

Streit's matzo bakery still makes unleavened bread for a national and

international market at the Rivington Street address where the company

was founded in 1925.

Russ & Daughters, the smoked-fish and caviar store, occupies the same

white-tiled East Houston Street shop where it has been since 1914. Yonah

Schimmel Knishes has survived, and Guss's Pickles has found a new lease

on life near the Tenement Museum. The owners of Noah's Ark, a kosher

restaurant in Teaneck, N.J., will open a branch on Grand Street by

year's end.

Perhaps not surprisingly, one of the few merchants who has no intention of

moving is the area's last gravestone seller. "We own the building here,

and people know where we are," said Murray Silver, the 60-year-old owner

of Silver Monuments on Stanton Street, a business dating from the late

30's.

Still, gravestone sellers aside, what kind of real future does the Jewish

Lower East Side face? Is there enough left to make Jews feel they can

find a link to a Jewish past? Or has too much vanished?

"You can find it at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum, you can find it

in walking tours," said Samuel Norich, general manager of the Forward

Association, which publishes weekly Jewish newspapers in Yiddish,

Russian and English from its home on East 33rd Street. "There are enough

remnants of Jewish life on the Lower East Side and life going on now

that you can build on and conjure up what used to be there.

"In words at least."

Most evenings, Rabbi Schmuel Spiegel roams the streets outside the First

Roumanian-American Congregation in search of a minyan, the 10 men

required for daily prayers.

Schapiro's Kosher Winery sold its building and left two years ago.

Copyright The New York Times Company

|

Jewish-American History - Uprising on

the Lower East Side, 1909

On November 22, 1909, thousands of workers,

mostly young, Jewish, and female,gathered at Cooper Hall in New York

City for a meeting that would initiate a new chapter in American labor

history and in the role of Jewish immigrants in American society. The

meeting had been called by Local 25 of the struggling International

Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, looking to reinvigorate their

degenerating strikes at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company and the

Leiserson Company by calling a general strike of the entire New York

shirtwaist (ladies’ blouse) industry, then becoming one of the largest

segment of the largely Jewish New York garment industry. The general

strike called that night would become known as “The Uprising of 20,000”

and would drastically change the role of women and Jews in American

labor politics over the next several decades.

The American garment industry itself had

developed simultaneously with the waves of East European Jewish

immigration between 1880 and 1920, offering numerous opportunities for

work and advancement to the newly arrived immigrants. Advances in

technology, industrial organization, and transportation made the

mass-production of affordable clothing possible, which was in turn met

with an increased demand for new fashions and styles, especially in

women’s clothing. To meet this demand and increase their profitability,

manufacturers developed a system of subcontractors, sweatshops, and home

work, relying on the availability of cheap immigrant and female labor to

fill their orders. The International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union

(ILGWU) was formed in 1900, under the auspices of the American

Federation of Labor (AFL) and the United Hebrew Trades (UHT), to

represent and protect the workers in the ladies’ garment trades,

including makers of dresses, hats, blouses, and jackets. For the first

several years of its existence, the ILGWU barely survived, and even

considered disbanding in 1908. Local 25, which represented shirtwaist

makers in New York City and whose failing strikes the meeting at Cooper

Hall had been called to discuss, numbered only 100 members on the eve of

the Uprising. The low membership numbers and marginal survival of the

union was due to several factors. The first several years of the 20th

century were hard hit by recession, making it difficult for unions to

make demands that could be met by the employers. More importantly,

perhaps, was the general attitude of labor organizers of the time

towards women and Jews. The recent Jewish immigrants were seen by many

unions as a threat to the job security of their workers, as they were

seen as a source of cheaper and more easily controlled labor by the

bosses. They were also victims of more general anti-Semitic and

anti-immigrant prejudices, speaking a strange

language, dressing differently, and practicing a “foreign” religion.

Women were also maligned by the unions, for similar reasons: they were

typically paid less then men and so threatened to take jobs away from

male laborers. Also, women were not considered a “good investment” of

labor organizers’ time and efforts, as many worked in factories and

shops only until they were married and had children, at which point most

women workers withdrew from public labor, instead taking on the kinds of

work that they could do at home: laundry washing, taking in boarders,

and finishing garments parceled out by the manufacturers for home work.

When Local 25 called its meeting, then, few

in the labor movement were prepared to take the demands of ladies’

garment workers seriously, despite the fact that they made up over 80%

of the workforce (75% of whom were also Jewish). Debate went on for

hours, with the mostly-male union leadership endorsing a strategy of

patience and negotiation against the workers’ demands for a general

strike. The meeting seemed destined to result in a stalemate when a

teenage worker named Clara Lemlich, active in Local 25 and considered a

troublemaker by many, took the stage. “I am a working girl, one of those

striking against intolerable conditions,” she announced in Yiddish. “I

am tired of listening to speakers who talk in generalities. What we are

here for is to decide whether or not to strike. I offer a resolution

that a general strike be declared--now!”

The response of the crowd was tremendous,

and Lemlich’s resolution was quickly seconded. The union leadership was

entirely unprepared for the massive response in the garment trades.

20,000 workers,or more, left their shops and joined the pickets. Relief

centers were hastily set up to support the striking workers, most of

whom were women. Union leaders gained a new-found appreciation of the

capacities of women picketeers, as women were beaten by police and

“gorillas”(thugs hired by the employers to menace the strikers) yet

returned to the pickets once they were freed from jail and their wounds

had healed. The strike ran through the winter until mid-February, when

it was settled with a reduced work-week (52 hours) and some improvement

of conditions, but without the union recognition that the workers had

hoped for. The resolution of the strike was considered a defeat by many

of the workers at the time, but laid the foundations for future

victories. Local 25 emerged from the strike with a membership of

10,000--the first Local in the country to amass such high membership

rolls. Inspired by the success of this largely unplanned and unprepared

strike, the mostly-male Cloakmakers’ Union went out on strike later in

the year, with 60,000 workers leaving their shops and bringing the

garment industry to a virtual standstill. This strike was resolved with

the industry-wide “Protocol of Peace”, which outlined a system of

union-employer relations that greatly increased the accountability of

the bosses to their employees (though, as is always the case in American

labor history, it was never enough...). Most importantly, the Uprising

of 20,000 established the importance of Jews and women--and particularly

Jewish women--to the labor movement. Though they still had to struggle

to control the conditions of their resistance (as with the conditions of

their labor), women and Jews could no longer be ignored by any union

claiming to represent the worker.

|

|

NoHo History

In 1748, what is now Lafayette and Astor Place, was New York’s first

botanical garden, established by a Swiss physician, Jacob Sperry, who

farmed flowers and hothouse plants. A mile from what was then the edge

of the city, Sperry's gardens became the destination of weekend

strollers up Broad Way from Wall St and the City’s Common (at Chambers

St.). Fifty-six years later, Sperry sold his gardens to John Jacob

Astor, who then leased the property to a Frenchman named Delacroix.

Delacroix transformed Sperry's property into the fashionable Vauxhall

Garden, where New Yorkers could also eat, drink, socialize, and be

entertained by band music and, in the evenings, by fireworks and

theatrical events.

But, by 1825, with real estate values skyrocketing on nearby Bond,

Bleecker, and Great Jones streets, Astor cut a broad street reducing the

garden to half its size, when Delacroix’s lease was up. This

created Lafayette Place, christened by the Marquis de Lafayette himself

on his last visit to New York in July of 1825, from a platform raised at

the corner of Great Jones and Lafayette. (Visit

Historic Districts Council for background on efforts to Landmark

these very blocks) Astor realized

a great profit for the lots on Lafayette Place, named La Grange

Terrace

after Lafayette’s country home in France. The four northernmost

“mansions” remain as Colonnade Row.

The five southern most houses were

destroyed in 1902 to make way for an annex to Wanamaker’s Department

Store.

What is now Washington Square Park (two blocks from the current northern

portion of NoHo) functioned, from the early 1780s, as an eight acre

potter’s field and public gallows. But, the comparative seclusion

of the area began to erode when outbreaks of yellow fever and cholera

ravaged the core city to the south at City Hall, in 1799, 1803, 1805,

and

1821 and those seeking refuge fled north to the

wholesome backwaters of the West Village. The population increased

fourfold between 1825 and 1840. More shrewd speculators, like

Astor, subdivided farms, leveled hills, rerouted Minetta Brook, and

undertook landfill projects. In addition to the fashionable Astor Place,

Washington Square Park, still a potter’s field in1826, at the foot of

Fifth Avenue, became a military parade grounds and a spacious pedestrian

commons. On the perimeter of Washington Square, stately red brick

townhouses built in Greek Revival style drew wealthy members of society.

The crowning addition to this urban plaza was the triumphal marble arch

designed by Stanford White, erected in 1892.

The University of the City of New York (now New York University),

established itself on the northeastern corner of Washington Square in a

building completed in 1837. At the time it was a

nondenominational, private university, established in 1831 by

Presbyterian and Dutch Reformed ministers in response to the

conservative curriculum and Episcopalian control of Columbia College.

The original building stood at this site until 1894.

As this transpired, a wave of revolutions convulsing Europe precipitated

a growing American disdain for monarchies, fueling tensions between

working-class immigrants. The Astor Place Opera House, on the present

site of the District 65 Building (UAW), became the site of the Astor

Riot on May 10 1849, when vitriol between British thespian W.C. Macready, American actor Edwin Forrest and

Sixth Ward Boss Isiah Rynders, a knife-fighting, English-hating Tammany

politician, inspired anti-English mobs who stormed the Theater in the

second act of MacBeth setting it on fire.

The disturbance brought out the militia and the police, who killed 22

(more by some accounts) and wounded 48; some 50 to 70 policemen were

injured. .

between British thespian W.C. Macready, American actor Edwin Forrest and

Sixth Ward Boss Isiah Rynders, a knife-fighting, English-hating Tammany

politician, inspired anti-English mobs who stormed the Theater in the

second act of MacBeth setting it on fire.

The disturbance brought out the militia and the police, who killed 22

(more by some accounts) and wounded 48; some 50 to 70 policemen were

injured. .

Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a private

tuition-free college provided by Peter Cooper to educate workers, opened

in Astor Place in 1859, having also incorporated the Female School of

Design founded to provide women with an alternative to menial labor.

Public debates, lectures and speeches were held in the Great Hall, not

the least of which was one delivered by Abraham Lincoln in 1860.

In the aftermath of the Draft Riots of 1863, when Irish immigrants

fearing their jobs would be taken by Black laborers if they were

conscripted to fight in the Civil War, and during which 11 Black men

were murdered with horrid brutality, the southeastern edge of the

Village (NoHo and Nolita)) became “little Africa..

In the late 1800s to early 1900s the East Village

(NoHo's neighbor to the east) grew as the working class marched

northward from the South St. Seaport (post Revolutionary War) and the

Lower East Side (Civil War). This area pioneered social services

including still extant institutions: Boys Club Headquarters

(founded in 1876 1901) and a Young Women's Settlement House (1897).

These institutions for immigrants and poor Americans provided free birth

control, educational classes, libraries, and dental and health services.

From the1850s the area north of Houston and east of Bowery was called

Kleindeutschland for the throngs of German immigrants who lived in its

tenements and worked the ironworks, piano factories, gas works and

breweries south of 14th

St. When these immigrants moved to Yorkville, it became “Bohemia”

accommodating Eastern Europeans. Hundreds of tenement apartments

became cigar factories; storefronts showcased milliners and cobblers,

cabinetmakers and upholsterers.

Throughout, greater Greenwich Village steadfastly marched to its diverse

destiny as the spiritual, educational, and cultural avant guarde of the

City. It's sub neighborhoods-- NoHo, SoViLa, East Village, West

Village--became the site of art clubs, private picture galleries,

learned societies, literary salons, theaters and libraries.

Interspersed in this fabric, fine hotels and shopping emporia also

proliferated through the 1860’s. As the poor and working class

poured into the East Village, older residences were subdivided into

cheap lodging hotels and multiple-family dwellings, or demolished for

higher-density tenements. Plummeting real estate values prompted nervous

retailers and genteel property along the Village’s Broadway corridor to

move north to Union Square.

|