Theodore L. DeVinne was the city's best and

most noble printer of the late 19th century. Built only with a modest

budget, DeVinne and his architects created a printing press/factory

building which attains a very high aesthetic standard. One of the most

impressive industrial facilities to rise in New York, the design is bold

but simple and appropriate for its function. An outstanding example of

the industrial building type from the late 19th century, this building

is still admired by architects and New Yorkers alike.

Streetscapes/De Vinne Press Building,

Fourth and Lafayette Streets;

An Understated Masterpiece That Earns Its Keep

By CHRISTOPHER GRAY

Published: April 13, 2003, Sunday

THE De Vinne Press Building is among the most sophisticated works of

masonry in New York, a tour de force of honestly simple bricklaying

built for one of the premier printing companies of a century ago. As

work crews repair the terra cotta cornice, the owner, Edwin Fisher,

looks back on two decades, starting with his purchase of the 1886

structure as a backup location for his Astor Place liquor store a block

away.

Mr. Fisher never had to move the store, but the De Vinne Press Building

has proved, for him, not just architecturally satisfying but also a

''financial bonanza.''

Although first developed in the 1830's as a street of top-tier urban

houses, after the mid-19th century Lafayette Place (renamed Lafayette

Street around 1900) evolved into a literary and cultural center. The

Astor Library (now the Joseph Papp Public Theater) was built there from

1853 to 1881, and Cooper Union was finished nearby in 1859.

After the Civil War, Lafayette and the surrounding streets began to fill

up with publishers, paper dealers, stationers, bookbinders, printers,

engravers and a broad variety of periodicals, like ''The Homeless

Child,'' an advocacy journal published out of the Mission of the

Immaculate Virgin at Lafayette and Great Jones Street in the 1880's and

1890's. The Aldine Club, for printers and publishers, was in an old

house just south of the Astor Library.

In 1886, Theodore De Vinne built a new building for his printing company

at the northeast corner of Fourth Street and Lafayette. De Vinne was

already established as a leading American printer; a founder of the

Grolier Club, an organization devoted to the history of printing, he had

printed the club's first publication, ''Decree of the Star Chamber

Concerning Printing.''

Born in 1828, he entered the printing business in the 1840's and printed

many of the leading American magazines, like the St. Nicholas Magazine,

Scribner's Monthly and The Century. A connoisseur of the printed work,

De Vinne wrote books like ''The Invention of Printing,'' ''Correct

Composition'' and ''Title Pages.''

He was successful in business but still considered printing nearly an art.

Writing in 1897 in the magazine The Outlook, he said that to try to

teach it was no better than giving ''a formula for the painting of a

picture or the writing of a poem.''

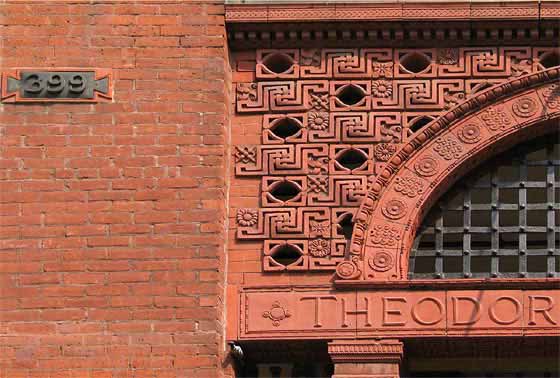

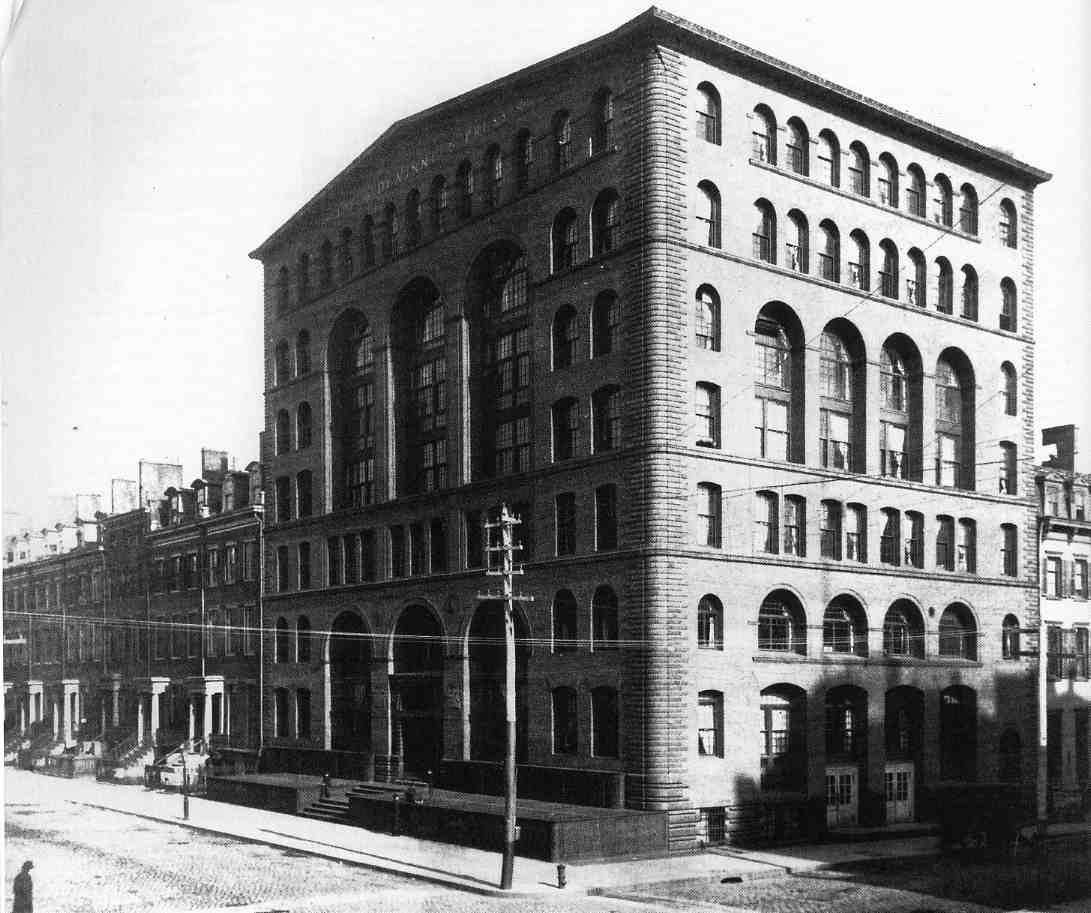

Designed by Babb, Cook & Willard, the De Vinne building is a masterpiece

of understated power, big, broad plain brick walls decorated almost

entirely by their own constructive elements -- strapwork quoining at the

corners, high deep arches, multipaned windows -- and a sweeping arcade

of window openings across the top. Writing in The Architectural Record

in 1904, the critic Russell Sturgis said: ''No photographs give the full

sense of its bigness, its breadth and its mass. More than once visitors

on their way to see it have been pulled up suddenly by a sudden sense of

its large presence.'' It seems out of place in New York, more like some

brawny Midwestern factory.

De Vinne died in 1914 and in 1922 James W. Bothwell, president of the

company, announced that the press would cease operations. ''Labor unions

are absolutely prohibitive of fine work,'' he said, but also added that

''the last thing people want to pay for today is quality.'' The building

later became a metalwork factory.

De Vinne's building, along with most Victorian architecture, was in

eclipse by the mid-20th century, although the critic Lewis Mumford went

out of his way to call it ''a special bouquet'' in The New York Times in

1953. In the rediscovery of the city's architectural history beginning

in the 1960's, it was designated a landmark in 1966.

In their book ''Rise of the New York Skyscraper (Yale, 1996), Sarah

Bradford Landau and Carl W. Condit call it ''one of the nation's

outstanding architectural monuments,'' tracing its muscular, arched

character back to the German rundbogenstil of the mid-19th century.

And the architectural historian Mosette Broderick, who has studied the

work of Babb, Cook & Willard, says of the building, ''Wow.'' The area is

utterly changed from only a generation ago. Where bales of rags and

pallets of wire rope once filled the sidewalks, now they are crowded

with N.Y.U. students and tourists bored with SoHo.

Mr. Fisher, who owns the De Vinne Press Building, has seen this himself.

After World War II he started what became a chain of 24 liquor stores in

New Jersey, and in 1960 bought a Manhattan store -- what is now Astor

Place Wines and Spirits, now a large operation at the southeast corner

of Astor Place and Lafayette Street. He had made a policy of owning the

buildings of his New Jersey stores, but the owner of the Astor and

Lafayette building would not sell.

SO, as insurance in case he lost his lease, Mr. Fisher bought the De Vinne

Press Building in 1982 and ran the De Vinne building as a real estate

investment, retiring from the liquor business, which his son Andrew now

operates. ''I get here at six in the morning and leave at four -- I'm in

my low 80's, and this is all I do,'' said Mr. Fisher, who seems very

vigorous for his age. He drives down from his apartment building in the

East 60's and, ''at that hour, I'm here in 12 minutes,'' he said. His

office faces south, and he sits against a background of an original

giant, round-topped window of 67 panes -- ''The windows are still good

-- why get rid of them?'' he asked.

Because of the huge windows -- which provided illumination for the

intricate work of publishing -- the interiors are high and light. The

offices of the architect David Paul Helpern, who has 11,000 square feet,

have arched brick ceilings painted white, resting on red painted

supporting beams, held up by cast iron columns. The columns are bare

except for a peculiar, perhaps Egyptian-style faceted capital that

shifts into an octagon shape, repeated by a collar farther down the

shaft.

If you cannot get into one of the offices, you can see these in the

Serafina restaurant on the main floor, entered through a majestic set of

iron gates -- which are a thrill to swing back and forth.

Mr. Fisher has gradually made improvements over the years, and is working

on a repair of the projecting cornice, in a $65,000 alteration designed

by the engineers Vincent Stramandinoli & Associates. ''This building has

been a financial bonanza -- it must be six or seven times what I paid

for it; rents were originally $5 per square foot, and now they're

getting to $30,'' Mr. Fisher said. ''I will not spare money to keep this

building looking the way it should.''

Published: 04 - 13 - 2003 , Late Edition - Final , Section 11 , Column 1 ,

Page 7

Copyright New York Times.

|