|

New York Architecture Images- Lower Manhattan

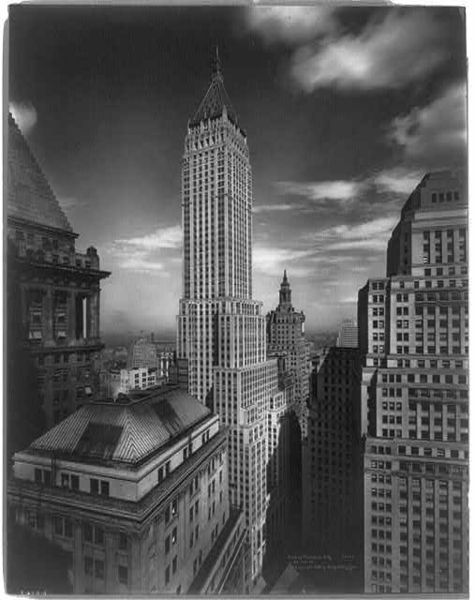

TRUMP BUILDING originally The Bank of

the Manhattan Company building

Landmark |

|

architect |

H. Craig Severance & Yasuo Matsui,

Shreve & Lamb Engineers: Starrett Bros. & Eken Clients/Developers:Bank of Manhattan Trust Company |

|

location |

40 Wall Street between William and Broad Streets |

|

date |

1930 |

|

style |

Art Deco |

|

construction |

281,8m / 927.0ft.120.141sq.

m. / 1,300,000sq. ft.72 floors steel structure limestone |

|

type |

Office Building |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

images |

|

|

|

|

|

In the first third of the 20th Century, Lower Manhattan was New York City's, and the world's, fabled, romantic skyline. The first generation of major skyscrapers, highlighted by the Singer, Woolworth and Bankers Trust buildings, had very distinctive silhouettes. The second generation of major downtown skyscrapers - the A.I.G. Building, 40 Wall Street, One Wall Street and 20 Exchange Place - were much thinner and close enough together to create the illusion of a forest arising out of the shrubbery of mere 20- and 30-story towers. With the virtually simultaneous completion of these towers in the early 1930s, the Lower Manhattan skyline assumed a magisterial place in urban iconography. While not symmetrical, its massing rose toward the center with considerable grace. It was a form that was not significantly altered until 1960 with the erection of One Chase Manhattan Plaza, a very important building that significantly helped bolster the downtown office market because of the major commitment to the area by the bank and a very stunning corporate headquarters building designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, but it was a project whose overwhelming bulk dominated the skyline. Its elan was imposing but it de-graced the skyline. The Chase building also had a very large plaza with a nice Dubuffet sculpture and it would soon be followed by the very elegant black tower known as 140 Broadway, whose plaza was adorned by a great Noguchi modern sculpture of a red cube perforated by a cylindrical space. While these skyscrapers were in very "good taste" individually, their scale disrupted the rather lyrical ambience of Lower Manhattan substituting their kettle drum fanfares and culminating in the demolition of the great Singer Building, designed by Ernest Flagg and its replacement by the U. S. Steel Building (later to be known as One Liberty Plaza), a hulk of girders and broad windows. These three new towers were clustered near the center of the Financial District but other massive buildings were being erected along Water Street close to the East River, further transforming the gentle but steep mountain of Lower Manhattan into various ranges of jagged cliffs. The World Trade Center, of course, dramatically altered the Lower Manhattan skyline with its nicely proportioned and gleaming twin towers shifting the center far to the west. It would take more than a decade for this enormous "tilt" to be somewhat rectified by the creation of the World Financial Center at Battery Park City, a commercial complex of 40- to 50-story office towers clustered about a great Wintergarden complex that directly faced the Hudson River and a "large yacht" basin. The tragic events of Sept. 9, 2001 in which the World Trade Center was demolished by terrorist attacks using airliners, of course, radically altered the skyline again. The twin towers are gone and are likely to be replaced with smaller buildings, but the sprawling and impressive built-environment of Battery Park City is largely intact and continuing to be developed. The focusing of intense interest on the "lost" World Trade Center, and what kind of memorial for the approximately 3,000 persons who perished in the attacks and what kind of redevelopment is appropriate for the huge site, has brought more public attention to the Lower Manhattan skyline than ever before. In the process, the World Trade Center's myriad images have glorified its stunning shininess and soaring forms and its great engineering and façades are more appreciated than ever before. Indeed, they are now remembered mostly in their best light, in the post World Financial Center-era when they did not appear to be about to teeter, or tiptoe, or totter into the Hudson River. Both the World Trade Center and Battery Park City were not perfect: the former had a windy plaza, very narrow windows that almost defeated the expectation of great panoramic vistas from its upper floors, and not terribly grand, albeit very busy, underground public spaces; the latter turned its back essentially on contemporary design and opted for a Post-Modern conservative development of what was probably the greatest waterfront site in the world. For a brief while, of course, before being surpassed by the far less handsome Sears Tower in Chicago, the World Trade Center were the tallest towers in the world and certainly they were fine and impressive symbols of power appropriate to the world's greatest city. The riverfront esplanade of Battery Park City and the awesome Wintergarden at its World Financial Center, on the other hand, were wonderful and spectacular and did much to overcome some of the banality of the World Trade Center's interiors. This is not the column to discuss what should be done with the World Trade Center site, but it is a place to begin to consider its context which is superbly illustrated and documented in this very fine book. The book concentrates of the four tallest Depression-era skyscrapers of Lower Manhattan, towers that are well-deserving of such in-depth examination and portraiture for they, together with the Singer and Woolworth buildings, really inspired the world with the steep, spectacular canyons they walled with crested aeries, cementing New York City's basic character as "high-rise," despite later-day, anti-high-rise activists who viewed virtually all proposed new construction as fatal threats to their neighborhoods and their sunlight and their "sense of place." Without such towers, New York City would just be another suburb, much to the delight of many of these activists. In her preface to the book, Carole Willis, the architectural historian and founder of The Skyscraper Museum, notes that while Wall Street is world famous its "physical place is indistinct" and adds that apart from a "few key towers" the skyscrapers of New York's Financial District "are oddly anonymous." "The skyscraper explosion in New York's financial district of the late 1920s and early 1930s," she wrote, "revolutionized the Lower Manhattan skyline. Instead of a broad plateau stretching from the Battery to City Hall, pierced by a few towers, there rose a great pyramid focused on Wall Street and surmounted by soaring new skyscrapers. Celebrated in art and mass culture, the financial district skyline symbolized twentieth-century New York's congestion, dynamism, and modernity. Subsumed within the ensemble, however, were the new building's individual identities.This book began as a study of the Wall Street area's tallest skyscraper, the 66-story AIG Building ( 1930-32), first known as the Cities Service Building and Sixty Wall Tower, and now also as 70 Pine Street.When completed, the 952-foot Cities Service Building was the world's third tallest skyscraper, after the Empire State and Chrysler Buildings. Owned by a large utilities conglomerate, the brick-clad Cities Service Building was `considered off the beaten path,' at the financial district's northeaster corner. Isolation enhanced the sculpted tower's prominence and helped its streamlined profile become a favorite subject of artists, including the photographer Arthur Fellig, known as Weegee, who thought it 'the most beautiful building of all.' The building's architects, the firm of Clinton & Russell, Holton & George (with Thomas J. George as designer), embellished the Cities Service Building's lobby in an exuberant Art Deco style, and placed a jewel box of an observation gallery on the 66th floor. Inspired and directed by Cities Service founder Henry L. Doherty as well as company engineers, the skyscraper was filled with the latest technology, including hot-water heating and double-deck elevators, plus an in-house gymnasium and law library to attract tenants to the upper rental floors." "Given its historically high land values and strong demand for prime office space, Wall Street," Ms. Willis wrote, "was surprisingly slow to give way to skyscrapers. Perhaps the conservative and clubby world of bankers was the reason that the nineteenth-century buildings with the posh executive offices, but limited areas of work space, survived so long, When the change came, the older structures collapsed as if on a fault line. If one mapped all the sites under construction in 1928 to 1931, the area would cover about a quarter of the financial district. These new towers of the financial district were different in character from the Art Deco extravaganzas of midtown. There were some flashes of glamour or example, the red and gold mosaic reception room at One Wall Street - but otherwise the Art Deco styling, even in such glorious cases as the Cities Service/AIG Building at 70 Pine Street, was restrained by standards of midtown where signature skyscrapers such as the Empire State, Chrysler, and RCA Buildings monumentalized their modernity in two-story lobbies. The star-power towers and a chorus of Art Deco dolls such as the Chanin, Fred French and Paramount buildings reflected midtown's more commercial character as a district that mixed business, shopping, and entertainment and that opened its storefronts to the street to seduce pedestrians. Downtown was a zone of work and interior environment of privilege and status." "It is disheartening," Ms. Willis continued, "to realize how much material on these commercial buildings and others less spectacular has been lost. There are, for example, no surviving records for architectural firms as important to the development of the financial district as Clinton & Russell, whose partnership, established in 1894, was responsible for at least a dozen downtown high rises, including the Broad-Exchange Building at 25 Broad Street and the Hudson Terminals, which early in the century were two of the largest office buildings in the city and the world. The firm continued under the name Clinton & Russell after the death of the principals in 1910 and 1907 and was rechristened Clinton & Russell, Holton & George in 1926. As architects of the Cities Service Building the firm produced one of the most inspired Art Deco Towers of the period and a building with numerous technological innovations, yet we cannot say with any certainty who in the office designed the tower or how the office functioned. We also know little about the operations of architects such as Trowbridge & Livingston, the blue-chip firm that nearly cornered the market on commissions at the intersection of Wall, Broad, and Nassau streets - the Bankers Trust tower, the headquarters for J. P. Morgan, and the office annex of the New York Stock Exchange, or of the brothers Cross & Cross, architects of the tower for City bank Farmers Trust, who practiced both design and real-estate development. While the notion of a deliberate race among the downtown towers is misleading, the idea of competition is essential for understanding any commercial architecture. Skyscrapers are business rivals, competitors for tenants, light and air, and prestige. Owners and architects like to distinguish their buildings from others, and height is one way to make a structure stand out. Great height has advertising value, because visibility and image-ability to create a sort of skyline logo. Likewise, naming a tower for a large corporation even if it is not the owner or major tenant, can lend cachet and help attract other upscale clients; this was the strategy at 40 Wall Street, where the building was promoted as The Manhattan Company Building by its speculative developers. As the country slipped into the depths of the Great Depression, the vacancy rate downtown climbed toward twenty-five percent. While Lower Manhattan suffered the effects of overbuilding for nearly thirty years, commercial construction revived more quickly in midtown where, especially on Park Avenue near Grand Central Terminal, many major corporations established new headquarters. Some of these, such as the Lever House the Seagram Building, and the Union Carbide Building, were striking statements of International Style modernism - prismatic towers rising from an open plaza. Their taut glass walls sealed in a new kind of office interior - an open plan, air-conditioned and brightly illuminated. Downtown's identity remained frozen in stone. For the first half of the twentieth century, the visual gravity of downtown's skyline and the center of gravity of New York's business community was Wall Street. But the centering forces began to weaken in the sixties. Downtown lost its dominance as the largest business district, slipping to third in the nation, after midtown Manhattan and Chicago, in the total volume of office space. A new shape and scale of construction overwhelmed the twenties towers. With the technology of fluorescent lights and cooled air, the floor plans of office building became solid rectangles without light courts. Reinforcing the aesthetics of the International Style, the 1961 zoning law replaced the setback form of base and slender spire with sheer-walled slabs, often surrounded by plazas. As working wharves receded into history, the biggest buildings rose at the edges of the island, along Water Street and on the west side."

"After the Cities Service Building, Mr. Abramson wrote, "the financial district's next highest structure was the 927-foot 40 Wall Street (1929-30), also known as The Manhattan Company Building and now the Trump Building). Initiated as a speculative development by the banker George L. Ohrstrom and the builder William A. Starrett, 40 Wall Street became the home of The Manhattan Company when that banking corporation included its site with that of the new skyscraper. The lead architect, H. Craig Severance and the probable designer Yasuo Matsui oversaw collaboratively the rapid construction of the brick-clad tower, capped by a pyramidal crest in a `modernized French Gothic' style, and with a Greek colonnade along its base. Inside, The Manhattan Company's architect Morrell Smith, assisted by the firm of Walker & Gillette, designed a grand second-story bank hall and American colonial style executive offices. The 71-story building contained more total office space (845,000 square feet) than any other financial district building constructed between the wars, much of it rented to financial service firms. "Next in height is the 760-foot City Bank Farmers Trust Building (1930-31, now 20 Exchange Place) made a distinctive impression at the financial district's southeast corner, its elegant chamfered shaft offset above the large trapezoidal base.Designed by the commercial and country house architects Cross & Cross (with George Maguolo as chief designer), the 54-story City Bank Farmers Trust Building embodied the venerable institution's culture. Stone-clad in limestone to a greater height than any other building in the world the `conservative modern' skyscraper featured emblematic art and a large wood-paneled senior officers' hall beneath the bank's eight floors of offices.

"The financial district's fourth highest tower, the 654-foot One Wall Street (1929-31) was built by the Irving Trust Company at the prestigious southeast former of Broadway and Wall Street, a site chosen to draw maximum attention to the bank. For similar reasons, the Irving Trust Company hired the artistically ambitious firm of Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker and, as a design consultant Yale art school dean Everett V. Meeks. The 50-story skyscraper's fluted, rhythmic limestone wall hung like a textured curtain over the step-backed mass and tower. Inside One Wall Street the design team including artist Hildreth Meiere, created a dazzling ground-floor reception room and a muraled tenants' lobby plus a three-story-high penthouse lounge for bank officials.

"Besides the four highest towers, a score of other major skyscrapers were erected in the 1920s and early 1930s in the financial district: an area defined by the real estate industry as roughly south of Maiden Lane between the Hudson and East rivers, with the John Street insurance district part of the area's northerly expansion.Large major office buildings by Ely Jacques Kahn, Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, and Clinton & Russell, Holton & George rose along John Street. Overlooking the Hudson River along West Street appeared skyscrapers by Starrett & Van Vleck and farther inland on Greenwich and Rector Streets, a 450-froot tower designed by Lafayette Goldstone. The district's prime north-south arteries of Broadway and Broad Street filled up with large corporate headquarters including the Standard Oil and Cunard buildings along Broadway and the Equitable Trust and Continental Bank buildings along Broad Street. Wall Street itself rose to new heights with a series of financial service headquarters by Trowbridge & Livingston, Benjamin W. Morris and Delano & Aldrich, and, near the East River, a pair of austere blocks by Ely Jacques Kahn and Schwartz & Gross." Daniel M. Abramson provides a short but good history of the financial district's architecture prior to World War I with some fine illustrations. He notes that Clinton & Russell had designed the 20-story Broad-Exchange Building in 1902 as the largest office building yet built with some 340,000 square feet of rentable space and that George W. Clinton and William Hamilton Russell of the firm would design in 1905 60 Wall Street, the first home of Henry L. Doherty and his Cities Service Company, and that many years later it would be connected by a 16th-floor bridge to the Cities Service Building, "the firm's swan song, produced under the guidance of partners Alfred J. S. Holton and Thomas J. George."

"The turn of the century building boom came to a resounding conclusion with a 1911 recession and the construction of the Equitable Life Assurance Building (1913-15) at 120 Broadway by the Chicago firm of Graham, Burnham & Company," Mr. Abramson observed. "This behemoth completed the prewar skyline and seemed to embody the skyscraper's general ill effects on the city. Since the 1890s critics has assailed skyscrapers for blocking neighbors' light and views, congesting street, offending aesthetic sensibilities, straining municipal services, devaluing adjacent properties, and endangering health by trapping noxious dust and vapors. Architects joined planners, engineers, public health experts, citizens, and businessmen in calling for restriction on skyscraper building, leading to the 1916 passage of New York's landmark zoning law.The Cities Service building and its contemporaries vied with each other for prestige, publicity, and tenants. Unique crests, fine materials, height, style, and beautiful lobbies distinguished one building from the other, bringing honor to owners and attracting tenants.Skyscraper rivalries were a serious matter, with millions of invested dollars at stake in each project, as well as architects' and owners' reputations. Still, there was a sense of commonality in the rivalry, a word whose later derivation, rivalis, means 'one who use a stream in common with another.' All the architects believed in the skyscraper form's capacity for beauty, efficiency, and profitability. All the owners believed in Wall Street's primacy as a business district and in the virtues of capitalism. Out of these shared convictions, as well a sense of rivalry, came the efflorescence of the Wall Street area skyscrapers." "Evolved from its early days as a commercial port, Lower Manhattan in the 1920s superceded London as the center of world finance," Mr. Abramson continued. "Ten separate exchanges specialized in stocks, bonds, cotton, coffee, sugar, metal, rubber and leather. Each day about half a million commuters streamed into Lower Manhattan. At the age of 35 [Henry L.] Doherty set up his own holding corporation, Henry L. Doherty & Company, in two 14th-floor rented rooms at 60 Wall Street, a 27-story building completed that same year by the leading commercial architecture firm of Clinton & Russell. By all accounts Doherty possessed boundless energy for his job, traveling around the country in a personal Pullman railroad coach or self-contained 'auto-trailer' complete with telephones and radios for keeping in touch with his corporate empire. For much of the 1920s the workaholic millionaire resided in a penthouse apartment of one of his buildings, 24 State Street, overlooking the Battery close by his Wall Street office. Doherty's penthouse contained a gymnasium, squash court, physical and chemical laboratories, movable wicker furniture, and a suite of offices and conference rooms. Indulging his taste for gadgetry, Doherty's bachelor aerie also feature various mechanical musical instruments, sixty-four telephone outlets, and a remarkable 'automotive bed' equipped with telephone, electric fan, and heating pad connections, mounted on rails and capable of being self-propelled from Doherty's bedroom through remote-controlled swinging doors onto an adjacent open-air sun porch. Doherty himself was widely credited with the initiative for the [Cities Service] building's double-deck elevators and aluminum terrace railings. The City Service building's glass observatory gallery was meant to be part of a new penthouse apartment for Doherty. Doherty never did reside atop the Cities Service Building, in part because he struggled for much of his later life with debilitating rheumatoid arthritis (thus explaining his penthouse's technological conveniences). From 1926 on he lived at the Kellogg Sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan, and in Florida before dying at the Temple University hospital in Philadelphia in 1939."

"The years 1929 and 1930," Mr. Abramson noted, "were the hottest for new developments. Developers eyed whole blocks between Broad Street and Broadway and along Wall Street toward the East River as likely sites for skyscraper projects never completed. Louis Adler planned a $20 million, 105-story building at 80 Wall Street. A. M. Bing & Son and the General Realty and Utilities Corporation proposed a $50 million Battery Tower residential development along West Street and the Hudson River (six decades before Battery Park City arose on nearly the same site.). Perhaps the grandest real estate vision belonged to Henry L. Doherty. At the tip of Manhattan, around Battery Park, the Cities Service magnate had amassed by the mid-1920s some $3 million and four acres' worth of real estate. With his holdings Doherty 'contemplated spending as much as $100,000,000 development an independent business centre for shipping and foreign interests.'A bird's eye view of Doherty's scheme shows the edges of Battery Park dominated by two imagined pyramidal skyscrapers topped by the Cities Service logo. Only in May 1931 did the financial district's overall occupancy rate dip below the normal industry standard of 90 % (with the opening of the Empire State Building and other large midtown buildings), while the rest of the metropolitan and national markets had nose-dived to an 83 % average." "After World War I had unsettled complacent attitudes toward the past and emboldened avant-garde experimentation," Mr. Abramson wrote, "many architects in the 1920s felt caught between the divergent poles of tradition and modernity. While some staked out hard-line claims (Gothicists like Ralph Adams cram versus modernists like Frank Lloyd Wright), most were left in the middle seeking some form of compromise. The architects of Wall Street's skyscrapers mainly occupied this middle ground. From a political point of view, Hildreth Meiere, muralist for One Wall Street, attacked 'Left Wing Modernists' on the grounds that 'human nature demands interest and relief from barrenness by some sort of enrichment.' Everett Meeks, One Wall Street's design consultant, considered 1920s European functionalism to be the particular result of that continent's postwar privation. In effect, New York architects enveloped skyscrapers in textured walls to help mediate ambivalent feelings toward tradition and modernity. On the one hand the textured wall abjured historical plagiarism in favor of integrally expressed modern materials. On the other hand the textured wall maintained the traditional architectural idea of an applied, unified façade whose beauty masks and gives mean to underlying structure." In March, 1927, Thomas J. George presented a plan to redevelop 60 Wall Street with a finned slab tower, and that October he enlarged the plan with a 60-story turreted tower, but the plan was rejected by city planners as too large for the site and Cities Service then decided to construct its new headquarters building across the street at 70 Pine Street.

"At night the Cities Service Building's pinnacle stood out in the floodlit glow of powerful 400-war Lucalox arc lamps, a profligacy of energy and light advertising the skyscraper on the metropolitan skyline, celebrating the modern 24-hour city, and honoring Cities Service's identity as an energy conglomerate," Mr. Abramson wrote. The building has a 16,000-volume law library on its 29th floor, a gymnasium, a 400-seat basement restaurant, a barber shop, and a hat cleaning and shoeshine shop. The building, Mr. Abramson noted, had an all-female corps of elevator operators and "Legendarily they were all young redheads and during the Depression 'recruited largely from the ranks of unemployed showgirls.'" The building's lower six floors are serviced also by escalators. Cities Service became Citgo and moved to Tulsa, Oklahoma and in 1976 the skyscraper was sold to the American International Group insurance company. In May, 1928, the Irving Trust Company announced plans for a new 46-story building on its site and two months later its architects, Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker revised the plan and proposed a 52-story tower. That plan would again be modified and in 1929 Irving Trust was granted a zoning variance for higher base street walls and shallower set backs. One Wall Street was, according to Mr. Abramson, "the financial district's most self-consciously ambitious work of art.Art Deco in many aspects, One Wall Street reflected architect Ralph Walker's articulate vision of modern designNo horizontal breaks whatsoever interrupt the elevation's verticality. Chamfered corners meld the Indiana limestone facades into a single whole.Walker's rhythmic 'fluting motif,' with an angled pitch of 1:9, echoed the syncopated window series and vertical 'reeding' of the landmark Woolworth Building, Irving Trust's quarters before One Wall Street. One Wall Street's complex fluted rhythms were motivated by Walker's belief that architecture should meet people's 'demand for beauty' and that 'advanced' civilizations require more beauty than 'pioneering' civilizations. For Walker architecture provided the best 'mental escape' and 'recreation for the mind' when its surfaces composed 'a pattern that is not easily read at a glancea unity not easily comprehended.'" "In One Wall Street's penthouse floors, the Irving Trust Company had a 48th-floor officers' dressing room and a 46th-floor officers' luncheon club with a fluted pier supported a polygonal scalloped ceiling. Most spectacularly, atop One Wall Street, lay Irving Trust's 49th-floor directors' observation lounge (also known as the great lounge), a soaring three-story room with ceiling-high windows, teak flooring, red marble fireplace, angled walls that mimicked the building's façade, and an informal array of living room couches, easy chairs, and tables. Thousands of irridescent Philippine kappa seashells sparkled on the ceiling, while a woven red tapestry patterned the walls with a stylized Native American war-bonnet motif. This décor alluded to modern imperial America's westward push across the Great Plains and the Pacific Ocean, as opposed to older European and early American colonial decorative identities." Instead of a banking hall, One Wall Street had a large and very spectacular reception room lined with "a shimmering skin of glass mosaic tiles," the author wrote: "At the wall's base, above a burgundy marble dado, dull flame red tesserae, pressed in cement and held in place by dark blue and black mortar, rose up and shaded into brilliant orange and golden yellow tiles that sparkled along the ceiling overhead. Veining the vibrant surface, jagged gold and silver lines drew together up the walls and across the shimmering ceiling, the chaotic skeins forming matching patterns in teach of the room's corner quadrants, enforcing a subtle order upon the walls' overriding movement. The stunning red and bronze walls of the Irving Trust reception room resemble a veined foliate forest or perhaps a rising range of crystalline mountains. 'What a room should do is lose its walls for your mind's sake,' Walker wrote in 1930, believing that movement, texture, and pattern provided 'recreation for the mind' and 'mental escape.'" The Irving Trust Company merged with the Bank of New York. In 1965, a southern annex in siilar style was designed by Smith, Smith, Haines, Lundberg & Waehler (the successor firm to Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker). In February, 1929, the development consortium led by George Orhstrom announced plans for a 47-story skyscraper for 34-38 Wall Street but revised them two months later when it had acquired the Manhattan Company's adjacent site and proposed a 64-story tower. In November, 1929, associate architect Yasuo Matsui drew up plans for an adjacent 50-story tower at 30 Wall Street but that plan was unrealized. Eventually, the consortium decided to built at 71-story tower. The building had a 55th floor Officers' Luncheon Club, a 58th floor Rookery Club and the Luncheon Club of Wall Street was located on the 26th and 27th floors. In 1946, 40 Wall Street was hit by a Air Force transport plane on the 58th floor and five people on the plane were killed. The Manhattan Company would merge with the Chase National Bank and vacate the building in 1960. The building would be owned by Webb & Knapp (the real estate firm formed by Eliot Cross), the Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos (in the 1980s), and, most recently, Donald Trump, who renamed the building after himself. Architecturally, 40 Wall Street lost its grand main banking hall and Ezra Winter murals, as well as Elie Nadelman's Oceanus during an early 1960s renovation of the tower's base. The remaining exterior received city landmark designation in 1995." "The major Wall Street area skyscraper with the most unusual massing is the City Bank Farmers Trust Building at 22 William Street, two blocks south of the Cities Service Building, which features a chamfered square tower offset above an irregular trapezoidal base," Mr. Abramson wrote. Initially, Farmers Loan and Trust Company and its architects, Cross & Cross, planned a 25-story building but when it merged with the National City Bank it revised its plans and proposed a 40-story building and eventually a 52-story tower. When National City planned to merged with the Corn Exchange Bank, new plans were made for a 75-story skyscraper that would, Mr. Abramson noted "resemble the Woolworth Building's Gothicized verticality and feature at its peak" an illuminated bronze sphere fifteen feet in diameter that would be supported by four colossal bronze eagles. The merger with the Corn Exchange Bank, however, fell through and the plans for the new building were scaled back, initially to 65 stories, and finally to 54 stories. The arched Exchange Place entrance of the City Bank Farmers Trust Building is framed by sculpted foreign coins that represented the foreign offices of the National City Bank and was designed by David Evans who "also designed the fourteen giant stone heads at the skyscraper's set-back 19th floor," seven of which are helmeted, "vaguely Greek and Assyrian 'giants of finance' bear scowling visages, while the alternate seven smile benignly." "The financial district's most monumental skyscraper lobby belonged to the City Bank Farmers Trust Building. A grand marble staircase in three parts led down to the National City branch office and up in the center, between thick marble balustrades, to the city Bank Farmers Trust senior officers' room. Along the rotunda's frieze and embedded in the floor were emblems of the bank's character, including a telephone and stock ticker, plus, for its architecture, a T-square, triangle, and bas relief of the building itself. Six giant marble pylons accented the austere surfaces and were articulated as bundled rods like roman fasces, representing strength and authority. These were surmounted by American eagles instead of traditional axe blades. Up in the stepped-dome ceiling Cross & Cross applied bands of flat Art Deco silver and gray stenciling in blocks of abstractly classical wave and fret patterns, synthesizing tradition and modernity." In the building's tenants' lobby, Hildreth Meiere in collaboration with sculptor Kimon Nicolaides created a 66-foot-long ceiling mural, "Allegory of Wealth and Beauty" that is illustrated in this book but which has been destroyed or covered up. City Bank Farmers Trust became part of Citibank and the building, which received landmark designation in 1996, is known now as 20 Exchange Place. Its rotunda and the senior officers' hall are no longer publicly accessible. All four major buildings had pneumatic tubes, centralized vacuum cleaning systems and the City Bank Farmers Trust Building "also featured a building-wide liquid soap system for its bathrooms, with basement soap-making and storage facilities." Construction started: 1929 See also: 40wall.com

Like the Empire State Building, the 40 Wall has also been hit by an aircraft: in 1946 a US Coast Guard plane hit the building in fog, killing four people. Originally the headquarters of the bank of

Manhattan |

|

|

40 Wall Street 40 Wall Street is a 70-story skyscraper originally known as The Bank of the Manhattan Company building, but then became known by the numerical address when its founding tenant merged with the Chase National Bank to form the Chase Manhattan Bank. It later became The Trump Building. The building, located between Nassau Street and William Street in Manhattan, New York City, was completed in 1930 after only 11 months of construction. Architecture Its pinnacle reaches 927 feet (282.5m) and was very briefly the tallest building in the world, soon surpassed by the Chrysler Building finished that same year. The building is now also known as the Trump Building (which adorns the building currently) after a 1996 renovation by Donald Trump who had bought the building. In 1998, the building was designated a landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. The tower is the tallest mid-block building in New York City. However, being a mid-block building results in it losing much of its impact. Race to be the world's tallest building 40 Wall Street was planned to be 135 feet (41 m) taller than the nearby Woolworth Building, which was completed in 1913. Most important, the plans were designed to be two feet taller than the Chrysler Building's planned height of 925 feet (282 m). However, the Chrysler Building developers secretly changed the projected height of their building after 40 Wall Street was completed. A 125 foot (38 m) spire was secretly assembled in the Chrysler Building's crown and hoisted into place, fulfilling tycoon Walter Chrysler's dream of owning the tallest building on Earth. Such glory was shortlived, however, as the Empire State Building would be finished the next year, 1931. Miscellaneous The building was designed by H. Craig Severance, along with Yasuo Matsui (associate architect), and Shreve & Lamb (consulting architects). Der Scutt of Der Scutt Architect designed the lobby and entrance renovation[2]. It was hit by a United States Coast Guard airplane in 1946 during fog. The crash killed five people, and the pyramidal tower was damaged. Though zoned for commercial use only, it has been said that Governor Thomas A. Dewey took residence below the observation deck for a time. When Donald Trump bought the building, he intended to convert the upper half of it to residential space, leaving the bottom half as commercial space. However, today it remains 100% commercial space. Trump bought the building for just $8 million in 1995 before doing extensive renovations. He attempted to sell the building in 2003, expecting offers in excess of $300 million. However, such offers did not materialize and Trump retains control of the building. In the ninth episode of the fourth season of The Apprentice, Trump claimed he only paid $1 million for the building, but that it is actually worth $400 million. This episode aired November 17, 2005. On CNBC's The Billionaire Inside, Trump again claimed he paid $1 million for the building, but stated the value as $600 million, and $200 million increase from two years previous. The episode aired October 17, 2007 on CNBC. |

|