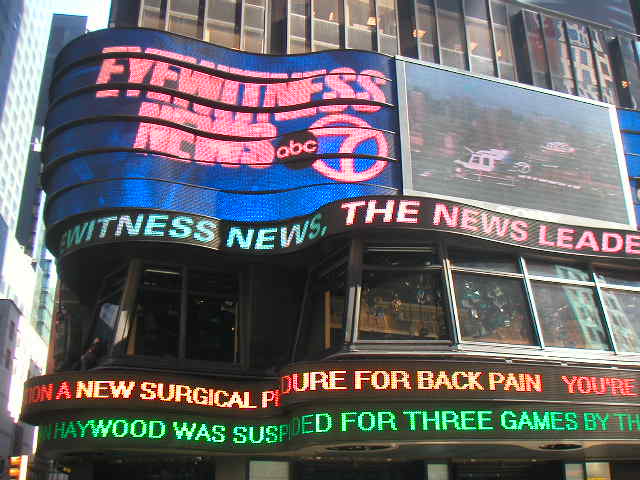

| By the end of

the 20th century, the entertainment industry has proven to be one of the

most influential industries on society. Entertainment currently dominates

society -- it is present everywhere. The 20th century first-world citizen

cannot claim it suffers from "too much work and no play." People are

entertained all day long, through every single media; radio, television,

film, audio, video, computers, internet, and print. If any place in the

world is famed for being the center of the entertainment industry in the

20th century, it is Times Square, having had the highest concentration of

entertainment industries. This essay is about Times Square, how it came into

existence, how it flourished, how it fell from grace, and how it is

currently being rebuilt. The text is divided into three parts.

The first part documents the "rise and fall" of Times Square as the

entertainment capital. Times Square became Times Square on April 9,

1904, when Longacre Square was renamed after the arrival of the New York

Times headquarters on the triangle between Broadway, 42nd Street and 7th

Avenue. The area arose as a cultural factory in the early 20th century,

and for many years remained the central marketplace for commercial

culture in the US. Infrastructure, land-use policies and other factors

caused the theatre and entertainment industries to cluster around what

later would be called the "crossroads of the world." 1 Amusements from

the newly invented theme park even found their way to the area,

democratizing the theatre. The excessive use of illuminated outdoor

advertising earned Broadway the name of the "Great White Way." Times

Square became one of the most frequently visited places by tourists,

drawn to the unprecedented commercial grandeur. Following the

introduction of movies (and "talkies") the area served as the nation's

center for motion pictures for some time. The ever-present sex industry

in Times Square eventually became dominant, followed by increasing

violence and drug use in the latter half of the century.

The second part looks more closely at the development of the amusement

parks on Coney Island, and the subsequent arrival of amusement-park

entertainment in the Times Square area. Originating from remnants of the

great expositions of the 18th century, the Coney Island amusement parks

became the first permanent mass entertainment. When two entrepreneurs

from Coney Island zeroed in on Manhattan, theatre and Times Square would

never be the same again.

The third and final part discusses the current developments of Times

Square, following decades of urban decay. After a long period of failed

attempts the area is being rebuilt. One of the major components of the

new scheme is the insertion of Disney as part of the urban

revitalization. In more ways than one, history is being recreated in the

area.

NOTES

1. Lying in the heart of midtown Manhattan, the area currently attracts 20

million tourists each year. "Of the 500,000 people who pass through the

Times Square subway complex each day, 250,000 walk through Times square

on their way to or from the trains, contributing to the neighborhood's

daily pedestrian count of 1.5 million." - Erika Rosenfeld, Times Square,

Times Square Business Improvement District publicity brochure, New York

1994 ; IMAGES: Times Square, postca rd. Photo: N.Y. Convention and

Visitors Bureau

PART ONE: CREATING TIMES SQUARE

It was no coincidence that Times Square became the great American

marketplace for commercial culture in the first decades of the 20th

century. Several conditions determined the location of what would become

the "crossroads of the world."

New York City had been for over a century the great center of

information circulation and the center for commerce with Europe. The

volume of imported and exported goods passing through the city's port

had grown rapidly throughout the 19th century, and New York moved far

ahead of its rivals, Boston and Philadelphia, in the import and export

of fashions, design, and ideas. This was also tied to the shift in

manufacturing that occurred between 1870 and 1900. While heavy

manufacturing moved towards the sources of raw materials, the industries

related to the production of cultural goods had to stay close to its

customers, in order to keep up with the latest fashions. Publishers,

manufacturers of women's clothing and all sorts of luxury goods

continued to flourish in the metropolis. With its enormous and widely

varied population, New York formed an unmatched marketplace and provider

of any conceivable service or supply.2

Transportation & Infrastructure

Economic and political conditions brought the market to midtown Manhattan.

Midtown was by 1918 the center of a complex web of local and national

transportation networks, bringing people of all classes, trades and

places to a single area. A long period of economic and political

decision-making had centered the different transportation networks

around mid-Manhattan. The location of the market for commercial culture

in that district became a by-product of these decisions. Grand Central

Station, at 42nd street and 4th (now Park) Avenue began as a railyard in

1840, and was frequently enlarged until 1913. Elevated railroads ran

over the city streets from the 1870s, but provided slow and dirty

transportation. This changed with the introduction of the subway, the

first line of which ran underneath a substantial length of Manhattan

island. In 1857 a ban was placed on steam-powered locomotives below 42nd

street to control smoke and fire pollution, forcing The Grand Central

Station to be built at that point. These decisions -- and many others at

the time -- had been made by the politically powerful economic elite to

protect and serve the city’s chief business and residential districts.

The intertwining of the various transit services made 42nd street in the

decades to follow one of midtown’s most important cross-streets. Times

Square became a key point as intersection of the elevated and subway

lines.3

While owners of already-developed property sought to keep the transit

facilities out of their neighborhoods, owners of less developed property

lobbied for the opposite, arguing that the absence of adequate transit

was unfairly holding their district back. The multiple subway lines met

the needs of several key economic interest groups, and accommodated

others by avoiding the avenues and boulevards they wished to protect.

That the subway gave a great locational advantage to Times Square, at a

time when theatrical entrepreneurs were on the move, was incidental.

Land-use Policies & the Garment Industry

National political and economic forces brought the market for commercial

culture to New York City; local transportation resolutions brought it to

mid-Manhattan. Land-use laws, such as the 1916 Zoning Resolution, pushed

the related businesses to the Times Square area.4 Midtown Manhattan

became a major center for retailing, garment manufacture, and other

businesses following the injection of the transit networks. Especially

the garment industry grew rapidly from the 1880s. Retail stores also

grew, some emerging as vast department stores in the early 1900s.

Retailers moved up Broadway, away from the expanding financial and

government office district, in search of better access to their

customers. They were closely followed, however, by the garment

manufacturers, who wanted to minimize their own transport costs and

maximize their access to buyers. While the retail and department stores

were greatly welcomed uptown, residents of the more fashionable areas

tried to keep the manufacturers out, complaining that the industrial

look of these districts made (women) shoppers feel unsafe and

uncomfortable. The retailers of Fifth Avenue had formed the Fifth Avenue

Association, and threatened to boycott any manufacturer who located in a

loft above 34th Street. The Fifth Avenue Association and several other

business associations supported the Zoning Resolution of 1916, which

excluded industrial activities from districts designated as commercial,

and specified Fifth Avenue and Broadway as commercial districts. As

result of the Zoning Resolution and other governmental and private

incentives the industry was moved to the west side of mid-Manhattan. The

area between Broadway and Eighth Avenue and 35th and 40th Streets is

still known as the Garment District. Subsequently, the theatres in this

area began to disappear. It would have been impossible to have matinee

performances when the narrow streets were filled with the business

activities (crowds of workers, vehicular traffic, garment racks) during

the day. At the end of the nineteenth century, New York's theatres were

scattered all around the city, but many disappeared in the following 25

years. In the same period, over 80 new theatres were built in and around

Times Square. Further land-use laws pushed the theatres away from Fifth

Avenue and up to Times Square.5

The Zoning Resolution of 1916 did not create New York's garment or theatre

districts, nor did it protect these districts. The zoning regulation had

been written to reduce congestion in the city, but the congestion of the

theatre district was recognized as both a cause and effect of the

concentration of transit facilities. Property owners raised their rents,

making it impossible for the smaller theatres, with only a handful of

performances a week, to stay open. The more profitable movie houses came

in their place, showing films to larger audiences throughout the day. By

1925 many proposed theatres were combined with large office buildings

and hotels. The nearby Rockefeller Center and Radio City (with its Music

Hall) was a typical culmination of these tendencies, combining

entertainment with massive office towers.6

NOTES

2. David C. Hammack, "Developing for Commercial Culture", p.36-38,

Inventing Times Square - Commerce and Culture at the Crossroads of the

World, William R. Taylor, editor, New York 1991. Resulting from a

succession of conferences on Times Square held in 1988-89, the book

contains numerous essays describing different aspects of Times Square's

cultural history. 3. "Developing for Commercial Culture", p.38-42 4. The

1916 Zoning Law is best known for describing the bulk envelopes of

skyscrapers, resulting in the many "setback" or "wedding cake" buildings

that can be seen in midtown Manhattan. Hugh Ferriss drew the famous

renderings exploring the limits of the Zoning Law for his book

Metropolis of Tomorrow (New York, 1929). Thomas A.P. van Leeuwen

describes his scepticism of this seemingly democratic law in The Skyward

Trend of Thought, (Den Haag, 1986). Aside from legislating the growth of

buildings in the commercial districts, it regulated land-use for

Manhattan. 5. "Developing for Commercial Culture", p.42-45 6.

"Developing for Commercial Culture", p.49-50 ; IMAGES: Times Tower,

postcard c. 1904; Times Square, postcard, date unknown

URBAN TOURISM

Another important link in the chain of events that helped create Times

Square was the birth of the American urban tourist in the early

twentieth century. During this time, cities became aware of themselves

as tourist attractions, and effectively turned it into a flourishing

business.

Many tourists visiting New York were drawn specifically to and

stimulated by business, by merchandisers, both as a consumer and a

visitor. In the late 19th century, Americans had learned from the

well-organized Swiss, who welcomed over three million visitors each

year, how to become successful hosts. Switzerland's prosperity was based

on the self-conscious development of foreign tourism, which had been

turned into a distinct profession.7

The fierce competition among the American cities to host the Columbian

Exposition of 1893, indicated awareness of the economic benefits that

could be obtained by the winner. The Columbian Exposition demonstrated

as one of the first in the US, a tight co-ordination between

hotelkeepers, railroad managers, publishers and city officials to ensure

that a huge mass of visitors could be moved around, housed, fed and

entertained in an efficient as well as a profitable manner.8

Meanwhile, a world-wide "competition of capitals" was taking place, and

the great fairs temporarily provided a landscape worthy of comparison

with the great European capitals. Urban planners promoted that urban

beautification could benefit behavior, civic pride, political morals,

real estate values, business efficiency, and tourism. The City Beautiful

movement ensued, and many cities turned to the serious business of

creating a permanent exposition of civic structures, museums, and public

squares. 9 In his presentation of his 1909 Chicago Plan, Daniel Burnham

noted that "People from all over the world visit and linger in Paris. No

matter where they make their money, they go there to spend it. . . . The

cream of our earnings should be spent here . . . while the city should

become a magnet, drawing to us those who wish to enjoy life." He

continued to say that "our own people will become home-keepers, and the

stranger will seek our gates."10

New York, in the 1890s, was already the most visited place in the country,

containing numerous 'places of interest.' The Statue of Liberty, the

Brooklyn Bridge and the city's great park that held two major museums

and a zoo, had all appeared within the last two decades. New York hosted

and exploited several mass-celebrations starting from 1885, attracting

millions of visitors. The city increasingly became a center for

conventions, trade associations, and shopping trips. The city became

dominated by strangers, stirring up a mixture of reactions from New

Yorkers. Some tourists headed for the traditional uplifting sights --

museums, monuments, parks, churches, and libraries. But many more were

drawn to the city's pleasure zones. Critics worried about the

experiences of these tourists, and complained about the wrong image that

New York might suffer. A whole market evolved around the rich visitors,

who could afford lavish tips and high prices. However, "The stranger's

New York is a surface New York," a writer for Outlook magazine noted.11

This was a comfort that even the humblest New Yorker could take, who was

locked out by the lavish pleasures, but was knowledgeable and blasé

about things that took the breath away of the ill-behaved

out-of-towners.

The Times Square area, or the Tenderloin as it was more commonly known in

the early 1900s, was viewed as an expensive, isolated tourist center

congested with nightclubs, theatres, hotels, and restaurants. Robert

Shackleton wrote that the average tourist was probably respectable

enough at his home in some distant city, "but on Broadway he is likely

to get a fifty cent cigar between his teeth and fling extravagant tips,

and become arrogant and boastful, and make it clear 'he has the price.'

It is this class of men who, inviting and receiving the attentions of

swindlers and robbers and sharpers, gets into police courts and gives

New York more of a reputation for wickedness than it deserves."

Shackleton noted that "A great part of the people who move along the

'Great White Way' are not New Yorkers, but visitors,"12 while Harper's

Weekly had pointed out that the so-called New York theatre audience was

not local at all. Contemporary journalist Julian Street wrote a series

of articles on the Tenderloin, and remarked that the natives looked

"with pity and amusement at those who are not of it." He continued to

say that "They [the visitors] stare at New York as a New Yorker stares

at Coney Island. For New York is, after all, the Coney Island of the

nation."13

NOTES

7. Neil Harris, "Urban Tourism and the Commercial City", Inventing Times

Square, p.67 8. "Urban Tourism and the Commercial City", p.68 9. "Urban

Tourism and the Commercial City", p.68-69 10. Daniel H. Burnham and

Edward H. Harris, Plan of Chicago, Chicago 1909; New York 1970; "Urban

Tourism and the Commercial City", p.69 11. "The Spectator", Outlook 76

(May 1910) p.306; "Urban Tourism and the Commercial City", p.79 12.

Robert Shackleton, The Book of New York, Philadelphia 1920 p.214-215,

Neil Harris, "Urban Tourism and the Commercial City", p.81 13. Julian

Street, Welcome to Our City, New York 1913; Neil Harris, "Urban Tourism

and the Commercial City", p.80 ; IMAGES: "Listening to the Ballgame,"

1940, Photograph by Lou Stoumen

COMMERCIAL ENTERTAINMENT

Theatre and music industry

Theatre at the end of the 19th century can best be described as the

television of its day. Live performance was the dominant form of

entertainment, and also very profitable. Numerous entrepreneurs helped

create public demand for new forms of entertainment, combining financial

cleverness with a remarkable sensitivity to new markets and changing

public tastes. New York had become the starting point for touring

theatre shows, which had grown in popularity since its introduction in

the 1860s. Helped by the expansion of the nation's railroad network,

companies of actors appearing in a single show travelled from city to

city, providing its own music, costumes, and scenery. Since New York was

already being regarded as the theatre-capital, it is not surprising that

it became the headquarters for the touring companies. In 1904 over 400

theatrical companies toured the nation. Times Square was soon dominated

by the theatre industry; rehearsal halls, offices of theatrical agents

and producers, headquarters of scenery, costume, lighting and makeup

companies, theatrical printers and newspapers were concentrated in the

area, in addition to the many theatres that displayed the shows before

they went on tour. In a few years, New York had more theatres than it

really needed, but its expansion continued. In 1910, there were 34

theatres, most of them new, and most of them in the Times Square area.

In the 1919-20 and 1929-30 seasons, 50 and respectively 71 playhouses

were operating in New York, nearly all of which in Times Square.14

Other entertainment industries that proliferated in the Times Square area

were the publishers of sheet music and, for a short time, the production

of radio shows. The song-writing and sheet music market were

particularly big in the first third of the century. The music industry

was then commonly known as "Tin Pan Alley", after Monroe Rosenfeld’s

song describing the cacaphonic sound of the area. One of the most

successful songwriters of Tin Pan Alley was Irving Berlin, who owned his

own publishing firm, and is perhaps best known for his songs Puttin' on

the Ritz and White Christmas.15

Movie industry

From around 1910, movies were changing the market and the face of Times

Square. Vaudeville houses began incorporating movies into their

programs, and moviemakers expanded their offices in the area.16 The

Victoria Theatre, the greatest of all vaudeville houses, was torn down

to make way for a new movie palace, the Rialto. Theatrical producers

shifted their attention from roadshows to developing scripts that could

later be sold to movie producers. The number of road companies and

legitimate theatres in the US quickly declined between 1910 and 1925,

but the number of theatres in Times Square continued to grow, driven by

the prospect of selling material to the movies and the vast available

audience. The rise of the movies brought many larger theatres, movie

palaces and a host of related businesses to the area. Many production

companies first produced live shows in their own theatres, then made

them into films. Movie producers held their first screenings in Times

Square, with its unparalleled access to mass audiences and to the

metropolitan and theatre press. Many of these businesses soon moved to

Hollywood, although many remained in Times Square because New York

continued to provide much of the talent—as well as most of the

capital—for the new industry.17

Sex industry

Although generally believed to have moved in after Times Square's golden

age, commercial sex had always been around the area.

Entertainment and prostitution moved into the area after the 1850s, when

industrialization in lower Manhattan forced the less profitable land

uses uptown. Only a few decades before, the area northwest of Longacre

Square had been developed as an elite residential area. Wealthy New

Yorkers quickly abandoned their well-built brownstones as commerce and

entertainment made the area undesirable. By the early 1880s, many of

these brownstones functioned as brothels and "parlor houses". Within a

few years, prostitutes were a prominent and visible part of the 42nd

street community. In the early 1900s, prostitutes paraded up and down

Broadway between 27th and 68th street; observers noted that "ten to

twenty prostitutes" were "seen nightly on every block."18 Meanwhile, the

"sporting male" culture, celebrating male heterosexual sexual activity,

had grown more popular and more public. Men of all classes enjoyed the

personal freedom, promiscuity, extramarital sex, and physical isolation

from the nation's strict Victorian lifestyle that the Tenderloin

offered. The displays of heavy drinking, street gangs, sexual

aggression, and prizefight boxing in combination with the high amount of

sexual services being offered, characterized the sporting male culture.

Prostitution became an accepted part of city life, since there was

little that could be done against it. As it was being tolerated, many

sporting males felt no compulsion to conceal their behavior.19

"As everyone knows," a former police chief concluded in 1906, "the city

is being rebuilt, and vice moves ahead of business."20 Indeed, many

recognized a strong business enterprise in the organization of

commercial sex in the city. The French syndicate even recruited French

prostitutes abroad, and Tenderloin brothels made impressive profits,

averaging to $25,000 annually. After the passing of the Raines Law,

however, the brothels declined in popularity, and hotels became the most

profitable habitats of prostitutes. The Raines Law had been passed to

prevent liquor sales in saloons on Sunday, but it was legal to sell

drinks in hotels with ten or more rooms. As a result, many saloonkeepers

opened up hotels, adding thousands of new bedrooms to Manhattan, most of

them permanently occupied by prostitutes.21

Needless to say, not everyone tolerated the course of actions. As the

police became regarded as corrupt and ineffective against commercial

sex, numerous reform organizations began to appear. Fearing the historic

association of the theatre with prostitution, the Society for the

Prevention of Cruelty to Children successfully lobbied for a child

exhibition law that restricted the stage activities of children under

the age of 16. In 1897, the Forty-fourth Street Property Owners

Association (with the help of the police) were able to close the

prostitute-infested Sixth Avenue Hotel. Crime fighting and law

enforcement regarding sexual activity noticeably changed with the

success and aid of the Committees of Fourteen and Fifteen in the early

1900s.22 Police policy shifted from moral control to more serious crime,

leaving the regulation of sexuality to the private reform bodies. The

Committee of Fourteen became known for the most successful

anti-prostitution campaign in the city’s history. In 1905, the

organization succeeded in passing the Ambler Law, which eliminated the

majority of the so-called Raines Law hotels.23 Furthermore, the

Committee restricted the marketplace of prostitutes; property owners

renting to prostitutes and saloons permitting solicitation were

criminalized.

Similar organizations, meanwhile, were battling against immoral

performances on the theatre stages. Shows such as George Bernard Shaw's

Mrs. Warren's Profession and Richard Strauss' Salome were both closed

after a single performance.24

By World War I, the Times Square area had visibly changed. The red lights

had been replaced by the theatre's white lights, dubbing Broadway as the

'Great White Way'. Where once the elite institutions of culture existed

alongside the elements of the sexual underworld, now served as the

entertainment center for the masses; young and old, male and female,

resident and visitor. References to the neighborhood as the Tenderloin

declined, replaced by its official name, Times Square.

Nonetheless, Times Square remained the venue providing exclusive adult

shows and entertainment. Theatres continued to produce shows with erotic

appeal, clearly to the audience’s taste, but were continually attacked

by the private reform bodies. In a "Salon des Arts", visitors could view

thirty nude paintings, and watch artists in smock and beret produce

fresh masterpieces from the nude model on display. The Hubert's Museum,

which replaced the famous Murray's Roman Gardens after its downfall

during the Prohibition, specialized in freaks, bizarre acts, and a flea

circus, also displayed an exhibition of "Hidden Secrets" of sex,

courtesy of the "French Academy of Medicine, Paris."25

While the reform organizations had succeeded in disorganizing the sexual

underground economy in the 1910s, prostitution was never eliminated from

the area. Prostitution continued to exist around Times Square, albeit

more camouflaged. Hotels were required by police to secure the names of

male customers with no baggage, as well as prove that the women with

them were their wives. Prostitutes were forced to rely on bellboys,

waiters, taxi drivers and pimps to recruit customers. Many became call

girls, while some even worked out of taxis.

As prostitution in Times Square became less public after 1920, law

enforcement turned to the increasing homosexual activity in the area.

The theatrical milieu had drawn many gays to the area, offering jobs in

restaurants, clubs, hotels, the theatre industry, and more tolerance

than most workplaces. Homosexuality was judged by people who were

themselves often marginalized because of the unconventional lives they

led as theatre workers. Some men could be openly gay among their

co-workers, while the eccentricity of artistic and theatre people

provided a cover for men adopting gay styles in their dress and

behavior. Gay men met at most of the district's restaurants, some

becoming predominantly gay and developing a mild gay ambiance.26

Surprisingly, these restaurants and "speakeasies" proliferated and

became more secure during the Prohibition.27 All speakeasies, gay and

straight, had to bribe the authorities and warn their customers to be

prepared to hide what they were doing at a moment's notice. The popular

opposition to enforcement and the development of criminal syndicates

protecting the speakeasies, made it easier for the gay clubs to survive,

since they stood out less.

Visiting Times Square became more of a theatrical experience itself as

"fairies" and male prostitutes took to the streets, becoming part of the

spectacle. In 1927, the Times Square Building was reported as being a

"hangout for fairies and go-getters" that attracted crowds of sailors.28

Although the police periodically conducted roundups of hustlers and

fairies on the street, they could not close the streets in way they

could close a bar. After the repeal of the Prohibition in 1933, gay bars

proliferated, although many were short lived, since they were once again

easy to find. The bars serving homosexuals continued to be dependent on

systematic syndicate protection, but many gays sought out more secure

venues, or places less likely to be raided. Several bars and nightclubs

tolerated or even welcomed gays, so long as they remained discreet. Gay

men developed a number of codes to covertly alert each other to their

identities in public; by wearing certain clothes, introducing certain

topics of conversation, and using code words they could carry on

extensive and highly informative conversations whose real significance

would remain unknown to the people around them.29 As a result, the bar

of the Astor Hotel maintained its public reputation as a respectable

Times Square rendezvous, while its reputation as a gay rendezvous and

pickup bar assumed legendary proportions in the gay world. Similarly, on

some nights, the Metropolitan Opera on Broadway at 40th Street, became

the "biggest bar in town."

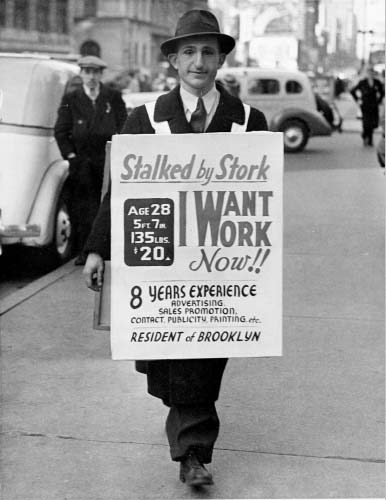

By the late 1930s, the Depression had hit hard upon Times Square. The

once-elegant restaurants had been replaced by cheap luncheonettes, and

crime kept many visitors away from the area's hotels. Meanwhile, Times

Square's white prostitutes were now known as almost the cheapest in the

city. Many of the legitimate theatres had turned into movie houses.

Commercial sex became once again visible in the area with World War II. As

servicemen flooded into Times Square, so did gay sexuality. After the

war, the economically supported revisions of the zoning laws in 1947 and

1954 did little to halt what many writers have called the downward slide

of Times Square. From the new zoning laws, adult cinemas and "dirty

bookshops" emerged in the area, selling souvenirs over the counter, and

pornography in the backroom. The sensational press reported that gays

and streetwalkers were more abundant and more conspicuous in their

abundance than ever before. In 1959, crime was low in the area with only

four drug arrests, no brothels, and only one legitimate nightclub. Male

hustlers were mostly seen on 42nd Street between 7th and 8th Avenues,

yet most arrests of males in Times Square in the fifties were for

brawling.30

image- with thanks

to Bernard Ente www.entephoto.com

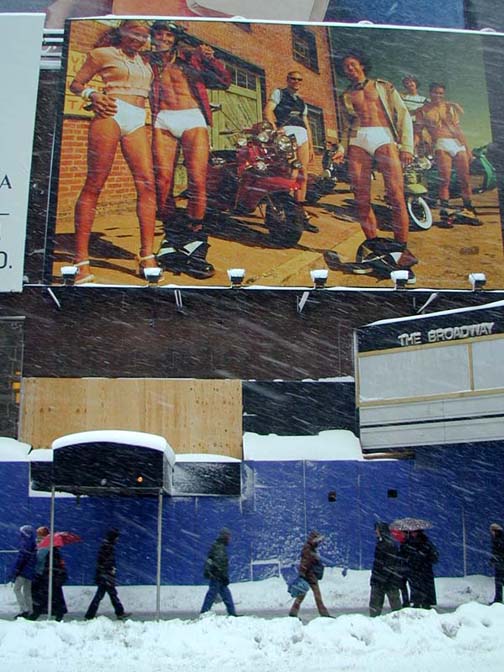

The 1960s brought an enlarged drug trade to the area, and with it the

elements of crime and violence. The libertarianism of the sixties caused

a boom in the already established sex business. Peepshows, massage

parlors, "adult" bookstores and -moviehouses, and prostitution quickly

became the dominant features of the area, continuing to do so for the

next two decades.

NOTES

14. Margaret Knapp, Introductory essay to section II of Inventing Times

Square, entitled "Entertainment and Commerce," p.121-122; David C.

Hammack, "Developing for Commercial Culture", p.45-48 15. Philip Furia,

“Irving Berlin: Troubadour of Tin Pan Alley”, Inventing Times square,

p.191-211 16. "Vaudeville first appeared in the 1880s. Composed of

seperate acts strung together to make a complete bill, it was the direct

descendant of mid-nineteenth century variety theatre, which had often

catered to carousing middle- and working-class men in saloons and music

halls. To attract these men's wives and families, creating a wider and

more lucrative audience, entrepreneurs banned liquor from their houses.

They censored some of their bawdy acts -- or at least promised to. They

jettisoned the older name of variety, with its stigma of vice and

alcohol, and adopted the classier sounding name of vaudeville." Robert

W. Snyder, "Vaudeville and the Transformation of Popular Culture,"

Inventing Times Square, p.134 17. "Developing for Commercial Culture"”,

p.48-49 18. Times (July 21, 1907); Timothy J. Gilfoyle, “Policing of

Sexuality”, Inventing Times Square, p.300 19. "Policing of Sexuality",

p.301, 303-304 20. William McAdoo, Guarding a Great City, New York 1906;

"Policing of Sexuality", p. 299 21. "Policing of Sexuality", p.305-306,

307, 311-312; Laurence Senelick, "Private Parts in Public Places,"

Inventing Times Square, p.331 22. "Policing of Sexuality", p.306-314 23.

"The Ambler Law required hotels built after 1891 and over 35 feet high

to be fireproof with walls 3 inches thick, rooms at least 30 square

feet, and doors opening onto hallways, thus eliminating most Raines Laws

hotels." Note from "Policing of Sexuality", p.307 24. "Policing of

Sexuality", p.310. Numerous other shows were battled for their content,

and reform bodies succeeded in closing many. Often, fines and short jail

terms were imposed on the authors, producers and actors. The list of

banned plays from the 1920s and 1930s includes Damaged Goods, The God of

Vengeance, The Demi-Virgin, Topics of 1923, Artists and Models, The

Captive, Sex, The Virgin Man, Maya, The Shanghai Gesture, and Pleasure

Man. see "Private Parts in Public Places," p.334-335 25. "Private Parts

in Public Places", p.332 26. George Chauncy, Jr., "The Policed: Gay

Men's Strategies of Everyday Resistance," Inventing Times Square,

p.317-318 27. "Speakeasy" was the contemporary word for cafe or bar,

particularly during the Prohibition, when they provided illegal liquor.

28. Miscellaneous Report, March 2, 1927, Box 36, C14P, New York;

"Policing of Sexuality", p.313 29. The word "gay" itself was such a code

word in the 1930s and 1940s. 30. "Private Parts in Public Places",

p.339-340 ; IMAGES: Houses of Prostitution in Longacre Square: 1901,

from "Policing of Sexuality," p.300; "Speako de Luxe," a speakeasy at

Washington Square, lithograph by Joseph Webster Golinkin, 1933; Jerry E.

Patterson, The City of New York, New York 1978

PART THREE: REBUILDING TIMES SQUARE

While Times Square continued to deteriorate throughout the 1960s into the

1980s, large scale redevelopments were being devised by the city. Most

of these schemes folded, or some proved unsuccessful. The Marriott

Marquis Hotel finally opened in 1985 more than ten years after its

initial proposal, promising an infusion of new life and capital in the

area. Instead, it had destroyed two theatres and had placed blank

concrete sides at street level.1

In 1984 the city presented the 42nd Street Development Project, a

subsidiary of the New York State Urban Development Corporation (UDC),

assigned to "reclaim" the area from clutches of crime and degradation.

Being the largest development effort ever undertaken by the State and

City of New York, and one of the largest urban renewal programs launched

in the US, it covers a 13-acre area directly around the stretch of 42nd

Street between 7th and 8th Avenues, commonly known as "the Deuce." The

Times Square envisioned in the 1984 plan, consisted of four skyscrapers

around the intersection of Broadway and 42nd Street, revitalized

theatres and a hotel and shopping mall on 8th avenue.2 The subsequent

designs for the office towers presented by Philip Johnson and John

Burgee in 1984 received such an amount of criticism, that the entire

plan was set back once again for several years. Furthermore, by the end

of the 1980s, the market for office space had collapsed, rendering the

proposed towers (for the time being) useless.3

image- with thanks to

Edward, www.wirednewyork.com

42nd Street Now!

The impatience for urban renewal is reflected in the name of the interim

plan that was presented in 1993; the "42nd Street Now!" project will

"ensure a rapid vitalization" of the area.4 UDC hired a creative team

consisting of graphic designers, lighting consultants, and architects,

amongst which Robert A.M. Stern, to draft a short-term plan that would

fit the area and attract investors. The plan focuses on creating a

highly varied mix of retail, eating and drinking establishments, tourist

attractions and entertainment. The sketches of the soon-to-be 42nd

Street depict an strongly enhanced version of itself; old and new

architecture juxtaposed, mixed and layered with illuminating signage

intensify the collective memory of Times Square. The signage is a very

serious part of the design guidelines; reports of the 42nd Street

Development Project continually note that the signage is Times Square's

major tourist attraction.5

The interim plan has proven to be a useful publicity tool. Despite the

claim that the renewed 42nd Street will not be "a gentrified theme-park

or festival market,"6 it owes much of its support to theme park giant

Disney. After several months of negotiations between the city and Walt

Disney Inc., the latter announced in early 1994, that it would

rehabilitate and reopen the landmark New Amsterdam theatre on 42nd

Street. The deal called for the city and state to lend Disney $21

million at 3 percent interest, while Disney itself spent $8 million of

its own to renovate the theatre. Politician hailed the announcement,

like Governor Mario M. Cuomo, who said "You're going to get rid of the

filth." According to other reports, however, this had been Disney's own

demand to the city before jumping in on the project in the first place.7

A new zoning law, going into effect in the fall of 1996, orders the

removal of residences, churches, schools and sex related businesses from

the area.

Following Disney's agreement and the passing of the zoning law,

hesitation towards the project from other leading entertainment

companies soon disappeared. In the same year six major hotel chains,

including Hilton Hotels, Marriott Corp. and the Walt Disney Co.,

submitted plans for the proposed hotel at the northeast corner of 42nd

Street and 8th Avenue. Along with the proposals by the hotel chains,

several other smaller companies, including restaurant concerns and

theatre operators, submitted proposals to establish businesses within

whatever is built on the site. For the final round of the design

competition in february of 1995, designs from Michael Graves, Zaha Hadid

and Arquitectonica were submitted, with the latter being approved for

construction. In September of 1994, MTV declared its interest in turning

three of the theatres on 42nd Street (including the Lyric theatre, the

place Robert de Niro in Taxi Driver dragged Cybill Shepherd to see

Swedish Marriage Manual), into an MTV Studio Complex, directly across

the street from Disney's New Amsterdam. The list of well-known

entertainment companies with big plans for Times Square continues:

Virgin Records said it would open its largest megastore on Broadway at

45th Street; Sony intends to build a high-tech movie cineplex, seating

6000; Madame Tussaud's will open its first animatronics wax museum

outside Europe.8

The 42nd Street Development Project owes its success in part to many of

the other organizations working to improve the area. In 1992 the Times

Square Business Improvement District (the BID) was established by area

businesses and community leaders to ensure make the neighborhood clean,

safe, and friendly. The BID put its own sanitation workers and public

safety officers in the street, and received $1.5 million from the Times

Square Public Purpose Fund to improve the sidewalk lighting in the

area.9 The New 42nd Street Inc., originally established as the 42nd

Street Entertainment Corporation in 1990, was given direct charge of six

of the 42nd Street theatres, which have been by the City and State.

Serving as the theatres' landlord, it was assigned to assemble and

select a mix of commercial and nonprofit tenants and operators and

furthermore promote the block's entertainment and cultural offerings.10

NOTES

1. Ada Louise Huxtable, "Re-inventing Times Square: 1990," Inventing Times

Square, p.362 2. 42nd Street Development Project, Update: Fall 1994,

Press release from New York State Urban Development Corporation, 1994.

3. Dale Arabi, "Will the New Times Square Be New Enough?," Wired 3.08

(August 1995), p.128-133, 172-173; "Re-inventing Times Square: 1990,"

p.363 42nd Street Now! 4. 42nd Street Development Project, Inc., 42nd

Street Now! Executive Summary, 1993 5. Allee King Rosen & Fleming, Inc.,

Parsons Bickerhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc., Eng-Wong, Taub & Associates,

P.A., 42nd Street Development Project: Genral Project Plan Amendment -

Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement, Executive Summary,

January 1994; 42nd Street Development Project, Inc.42nd Street Now!

Executive Summary, 1993; UDC, 42nd Street Development Project Design

Guidelines, May 1981, and Special Features Supplement, June 1981. 6.

42nd Street Development Project, Inc.42nd Street Now! Executive Summary,

1993 7. Douglas Martin, "Disney Seals Times Square theatre Deal," New

York Times (February 3, 1994), p.B1,B3; David Henry, "Landing Disney on

42nd," New York Newsday (February 4, 1994); Rudie Kagie "Mickey Mouse

verslaat de peepshows," Vrij Nederland 13 (March 30, 1996) 8. Thomas J.

Lueck, "Hotel Plans Are Submitted For Times Sq. - At Least 6 Chains

Offer Bids for Rundown Site," New York Times (July 30, 1994); David

Henry, "Disney Wants Hotel on 42nd St.," New York Newsday (July 29,

1994); Tom Lowry, "Another piece of 42d St. Puzzle," Daily News

(September 13, 1994); Martin Peers, "MTV eyes Times Square rock ‘n'

retail", New York Post (September 28, 1994); William Grimes, "MTV To

Make 42d Street Rock," New York Times (September 28, 1994); Robin Schatz

and David Henry, "MTV theatre? - Network eyes 42nd St. for entertainment

complex," New York Newsday (September 28, 1994); "Will the New Times

Square Be New Enough?" p.130-132; Herbert Muschamp, "3 Hotels for the

World's Crossroads", New York Times (February 17, 1995), p. B1 9. Erika

Rosenfeld, Times Square, Times Square Business Improvement District

publicity brochure, New York 1994; Erika Rosenfeld, Times Square

Business Improvement District, brochure, New York 1994 10. The New 42nd

St., Inc. press kit and site information, New York 1994 ; IMAGES:

renderings of the 42nd Street Now! interim plan, 1994

Disney and the Urban Amusement Park

In much the same way as once the Luna Park formula changed the face of

Times Square, the injection of Disney should reinvent the area as the

cross-roads of the world. Disneyland is today's Luna Park, and the

similarities are manifold.

Just as Luna Park was presented as a place far away from everyday life,

Disney World (in Florida) and the Disney Lands (in California, Japan,

and France) offer a similar escape from reality. Even more than the Moon

being the destination of the Luna Park visitor, Disney is a vacation

destination of its own. Disney World even has an official airline,

Delta, a perfect symbol for its nationhood. Visitors can pay with either

regular US Dollars or with "Disney Dollars", which can be exchanged one

to one at the entrance of the park. While the Mickey Mouse money offers

no advantage or discount in any way, it adds yet another degree of

foreign-ness to the park.11

And just like Luna Park, Disney is a descendant from the great expositions

of the 19th century, derived from the industrial revolution. The 1851

Great Exposition of the Works of Industry of All Nations held in London

was the first great utopia of global capital, displaying collected

modern technologies in the first entirely prefabricated winter garden.

Later, the fairs became differentiated, consisting of thematically

arranged pavilions (manufacture, transport, science, etc.),

entertainment oriented, national, and corporate pavilions. As the fairs

grew, they also began to showcase utopian urbanism, displaying the

cities of the future in both their pavilions as in their plans. While

most of the ideas originated from Europe, America became the tabula rasa

for utopian experiments.12

Alongside the City Beautiful movement which evolved from the fairs, came

the garden city movement, promoted by the Englishman Ebenezer Howard in

Garden Cities of Tomorrow (1902). Many of the patterns originating from

the garden city have been incorporated in the layout of the Disney

Parks. In short, these ideas included a radial plan around a single

center, the separation of pedestrians and vehicles, and functions in

walking distance. The 1933 Century of Progress Exposition held in

Chicago was the first to elevate all means of movement, pre-existing the

famous Disney monorail.

Even more closely related to the World Fairs is Disney World's

Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow (EPCOT). Located in the

vicinity of Disney World, a short and scenic monorail ride away,

everything about it resembles the great fairs: the garden city plan; the

geodesic sphere in the center; the corporate and national pavilions. As

in many Disney-rides, the visitors roll past perfectly orchestrated

animatronic scenes in tiny cabs, an invention also brought forth by the

World Fairs.13

One of the major goals of the 42nd Street Development Project is to

continue to attract the 20 million tourists that visit the area each

year. For such as purpose, it seems all the more fitting that Disney

take part in the plan. Amusement parks have continued to draw tourists,

and Disney is the undisputed world leader. The current course of actions

seems to follow the City Beautiful movement of the early 20th century.

The Beaux-Arts architecture of the great fairs had been viewed as a

great improvement to the city and a strong attractor of tourists.

Similarly, it is now believed that the Disney-esque "architainment" can

bring new life to the city. As the Beaux-Arts architecture was a baroque

classicist style relying on imagery of the past, the Disney-esque

architainment, ironically, recycles the honky-tonk Times Square / Luna

Park baroque onto the area itself. Disneyland's famous Main Street

Electrical Parade can be seen as mobile version of the Great White Way.

Nightly, the entirely illuminated carriages and vehicles of the parade

roll past the parks' visitors at the same pace one could walk across

Times Square, creating a similar experience. Likewise, typical Disney

architecture is an eclectic mix of past, present and futuristic styles

mixed, jumbled and juxtaposed for maximum effect.

Shopping and entertainment have continued to grow closer to one another.

The turn-of-the-century department stores were the first to promote mass

consumerism in the form of shopping, as an entertaining activity. Early

in their existence, department stores had already discovered that a

theatrical presentation of goods could fascinate its customers. Scenery

window displays transformed ordinary goods into more desirable goods.14

Throughout the 20th century, and especially in the last three decades, the

lines between retailing and entertainment have become blurred. Sports

stores have simulators to test athletic skills (and products); music

stores offer video performance and sometime live concerts; restaurants

like Planet Hollywood and the Hard Rock Cafe are the museums of popular

culture, all turning the experience of shopping and eating into an

entertaining and cultural event. "Megamalls," such as the gigantic West

Edmonton Mall in Alberta, Canada have turned shopping into an

over-the-top entertainment experience. According to the Guinness Book of

Records, it is the largest shopping mall in the world. The complex holds

a number of other Guinness titles, such as the World's Largest Indoor

Amusement Park, World's Largest Indoor Water Park, and the World's

Largest Parking Lot. The mall also holds a full-size skating rink, 13

nightclubs, 20 movie theatres, and a 360-room hotel, aside from more

than 800 shops, 11 department stores and 110 restaurants. The mall's

developers intended to make sure that the shops would have plenty of

visitors, creating a complete, self-contained entertainment city. In

much the same way as Daniel Burnham predicted that his plans would

attract tourists (see page 4), one of the mall's developers shouted at

the opening, "What we have done means you don't have to go to New York

or Paris or Disneyland or Hawaii. We have it all here for you in one

place, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada!"15 The combination of

'architainment' and retail seem to make a typical late 20th century

tourist draw. A massive shopping venue encased in merry architecture and

impregnated with entertainment are the city centers of tomorrow. It is

this set of images, in part derived from Times Square, that will be

re-imposed on the area itself.

Throughout its history, Times Square has been an exciting place. Despite

its degradation in the last third of the century, it continued to draw

millions of tourists each year. Entertainment businesses and theatres

remained in and around the area. As much as Times Square became known

for its adult shows and bookstores, it kept being known as a remarkable

entertainment district with a rich history and strong potential. Many

critics complain that the efforts of rebuilding Times Square are focused

on preserving myths and illusions, and emblematic characteristics. This

may well be, but one must not forget that Times Square was primarily

created and constantly altered by economic forces. One could argue that

Times Square is not just an entertainment district, it is an

entertainment business district. And as entertainers such as Thompson &

Dundy and Walt Disney have proved, entertainment is a good and

fast-moving business. It is only logical that they met at Times Square.

NOTES

11. Michael Sorkin, "See you in Disneyland," Variations on a Theme Park -

The New American City and The End of Public Space, Michael Sorkin,

editor, New York 1992, p.220, 223 12. "See you in Disneyland," p.208-212

13. "See you in Disneyland," p.212-216 14. Margeret Crawford, "The World

in a Shopping Mall," Variations on a Theme Park, p.14-17; William Wood

Register, Jr., "New York's Gigantic Toy," Inventing Times Square, p. 248

15. 42nd Street Now! Executive Summary, 1993; "The World in a Shopping

Mall," p.3-4 ; IMAGES: "Main Street Electrical Parade", postcard of Walt

Disney World, Orlando, Florida; "Future World", postcard of EPCOT

center, 1982

|