|

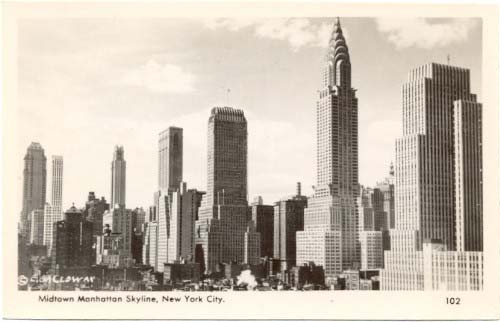

New York

Architecture Images- Midtown

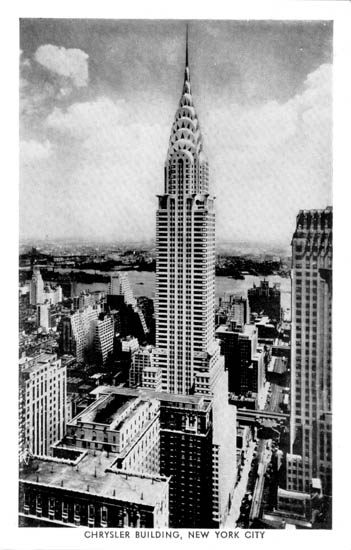

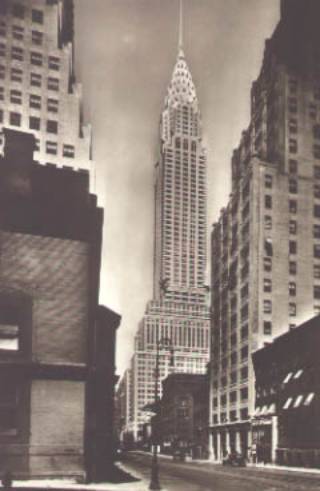

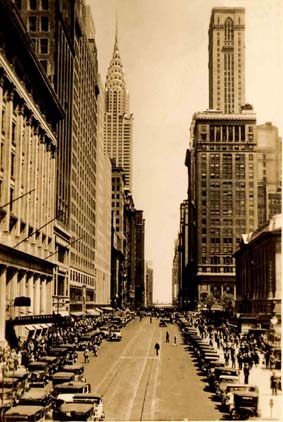

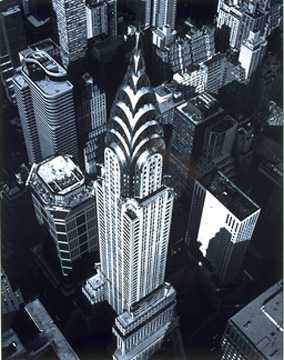

Chrysler Building

Landmark |

|

architect |

William Van Alen |

|

location |

405 Lexington Avenue at 42nd Street |

|

date |

1928-1930 |

|

style |

Art Deco |

|

construction |

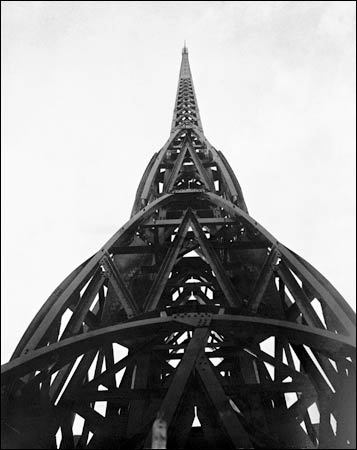

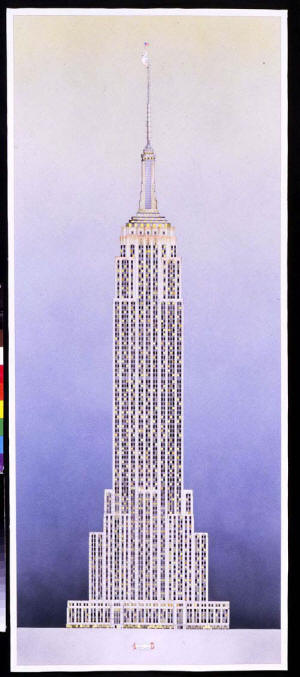

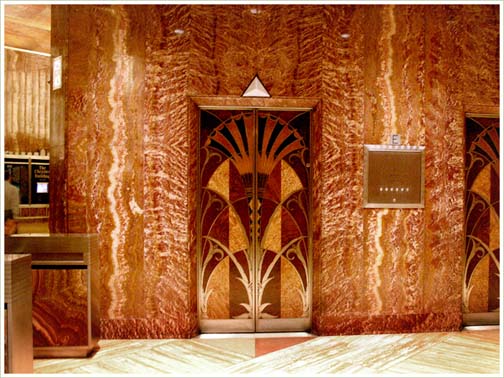

77 floors, 319.5m (1048 feet) high, 29961

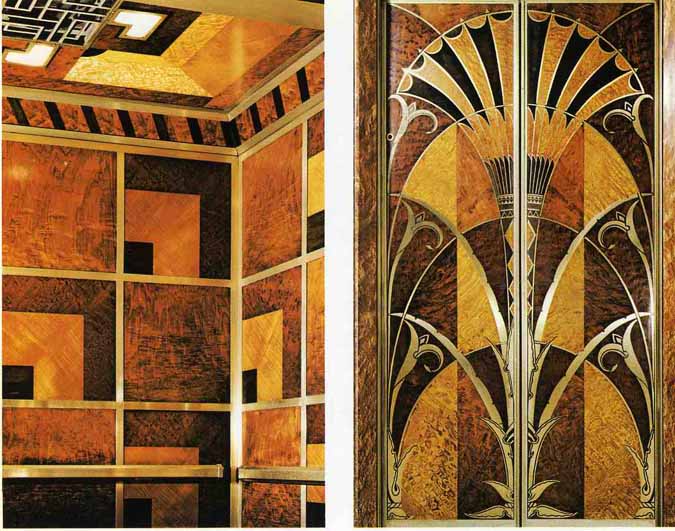

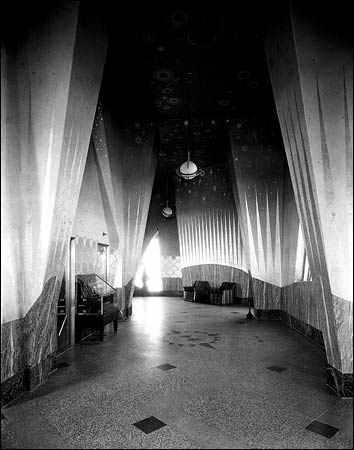

tons of steel, 3,826,000 bricks, near 5000 windows. Cost: $ 20,000,000 The building is clad in white brick and dark gray brickwork is used as horizontal decoration to enhance the window rows. The eccentric crescent-shaped steps of the spire (spire scaffolding) were made of stainless steel (or rather, similar nirosta chrome-nickel steel) as a stylized sunburst motif, and underneath it steel gargoyles, depicting American eagles (image), stare over the city. Sculptures modeled after Chrysler automobile radiator caps (image) decorate the lower setbacks, along with ornaments of car wheels. The three stories high, upwards tapering entrance lobby has a triangular form, with entrances from three sides, Lexington Avenue, 42nd and 43rd Streets. The lobby is lavishly decorated with Red Moroccan marble walls, sienna-coloured floor and onyx, blue marble and steel in Art Deco compositions. The ceiling murals, painted by Edward Trumbull, praise the modern-day technical progress -- and of course the building itself and its builders at work. The lobby was refurbished in 1978 by JCS Design Assocs. and Joseph Pell Lombardi. |

|

type |

Office Building |

| Click here for Chrysler Building gallery | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

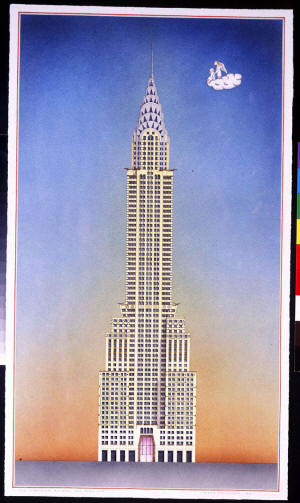

| Rendering copyright Simon Fieldhouse. Click here for a Simon Fieldhouse gallery. | |

|

images |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

notes |

What started

as a small speculative office building became one of New York's most admired

landmarks. Chrysler took over the lease of the office building when it was

in construction, hired William Van Alen to create a monument to his growing

company and, allegedly, asked the architect to build the highest building

constructed to date. To beat out his competitors who were also trying to

build the world's tallest building, Van Alen erected a 185-foot spire on the

top of the tower which was secretly delivered to the site in sections and

raised to the top in a mere 90 minutes. Only a few months later, the Empire

State Building surpassed the building in height, but the Art Deco skyscraper

remains an unparalleled monument to industry.

One of the first large buildings to use metal extensively on the exterior, the building's ornament makes reference to the automobile, the quintessential symbol of the machine age. Metal hubcaps, gargoyles in the form of radiator caps, car fenders and hood ornaments decorate shaft and setbacks of the white and black brick building. This aluminum trim culminates in a beautiful, tapered stainless steel crown that supports the famous spire. A private lounge called the Cloud Club and an observation area were located at the top of the building. A particularly beautiful example of the Art Deco style, the lobby is clad in different marbles, onyx and amber. It is decorated with Egyptian motifs and a ceiling fresco by Edward Trumbull entitled "Transport and Human Endeavor" that depicts buildings, airplanes, and scenes from the Chrysler assembly line. The building was landmarked in 1978 and it is now owned by Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company. |

|

|

By Jeff Glasser |

|

The Chrysler Building is an Art Deco skyscraper in New York City, located

on the east side of Manhattan at the intersection of 42nd Street and

Lexington Avenue. Standing at 319 m (1,047 ft) high,[1] it was briefly

the world's tallest building before it was surpassed by the Empire State

Building in 1931. However, the Chrysler Building remains the world's

tallest brick building.[2][3] After the destruction of the World Trade

Center, it was again the second tallest building in New York City until

December 2007, when the spire was raised on the 365.8 m (1,200 ft) Bank

of America building, pushing the Chrysler Building into third position.

In addition, the New York Times Building, which opened in 2007, is

exactly tied with the Chrysler Building in height, making the two

buildings tied for 3rd position.[4] Despite the change in tallness

ranking in New York, the Chrysler Building is still a classic example of

Art Deco architecture and considered by many, at least among

contemporary architects, to be one of the finest buildings in New York

City. History The Chrysler Building was designed by architect William Van Alen to house the Chrysler Corporation. When the ground breaking occurred on September 19, 1928, there was an intense competition in New York City to build the world's tallest skyscraper.[5][6] Despite a frantic pace (the building was erected at an average rate of four floors per week), no workers died during the construction of this skyscraper. [7] Design beginnings Van Alen's original design for the skyscraper calls for a decorative jewel-like glass crown. His design also features the building's base in which showroom windows were tripled in height and topped by various number of stories with glass-wrapped corners, creating an impression that the tower appeared physically and visually light as if floating on mid air.[8] The height of the skyscraper was also originally designed to be 246.0 m (807 ft) tall.[7] However, the design was proved to be costly. Hence, building contractor William H. Reynolds disapproved Van Alen's original plan.[9] The design and lease was sold to Walter P. Chrysler, who worked with Van Alen and redesigned the skyscraper for additional stories was later revised to be 282.0 m (925 ft) tall.[7] As Walter Chrysler was the chairman of the Chrysler Automobile Corporation,[7] various architectural details and especially the building's gargoyles were modeled after Chrysler automobile products like the hood ornaments of the Plymouth, and in which must also exemplify the machine age in the 1920s. Construction As construction proceeded on September 19 1928[7], over 400,000 rivets were used[7] and approximately 3,826,000 bricks which were manually laid by hand, was used to create non-loadbearing walls of the skyscraper.[12] Tradesman with specialized skills converged on the site. Contractors, builders and engineers were joined by other building services experts to coordinate construction. Prior to its completion, the building stood about even with a rival project at 40 Wall Street designed by H. Craig Severance. Severance increased the height of his project and then publicly claimed the title of the world's tallest building[13] (this distinction excluded structures that were not fully habitable, such as the Eiffel Tower)[14]. In response, Van Alen obtained permission for a 56.3 m (185 ft)[15] long spire and had it secretly constructed inside the frame of the building. The spire was delivered to the site in 4 different sections.[16] On October 23, 1929, the bottom section of the spire was hoisted onto the top of the building's dome and lowered into the 66th floor of the building. The other remaining sections of the spire were hoisted and riveted to the first spire section in sequential order in just 90 minutes.[17] Completion As construction was completed on May 28, 1930[7], the added height of the spire allowed the Chrysler Building to surpass 40 Wall Street as the tallest building in the world and the Eiffel Tower as the tallest structure. It was the first man-made structure to stand taller than 1,000 feet (305 meters). Van Alen's satisfaction in these accomplishments was likely muted by Walter Chrysler's later refusal to pay the balance of his architectural fee [18]. In less than a year after it opened to the public on May 27, 1930, the Chrysler Building was surpassed in height by the Empire State Building. Business dealings The Chrysler Building was bought in 1957 by real estate moguls Sol Goldman and Alex DiLorenzo, and later sold to the Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company. The lobby was refurbished and the facade was renovated in 1978 - 1979[19][20]. The building was purchased by Jack Kent Cooke, a Washington, D.C. investor in 1979. The spire underwent a restoration that was completed in 1995. The building was sold by Cooke's estate to Tishman Speyer Properties and the Travelers Insurance Group in 1998. In 2001, a 75% stake in the ownership of the building was sold to TMW, a German investment group[21]. The building was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976[22][23][24]. Architecture Detail of the Art Deco ornamentation at the crownThe Chrysler Building is considered a masterpiece of Art Deco architecture. The distinctive ornamentation of the building is based on features that were then being used on Chrysler automobiles. The corners of the 61st floor are graced with eagles, replicas of the 1929 Chrysler hood ornaments[25]. On the 31st floor, the corner ornamentation are replicas of the 1929 Chrysler radiator caps[26]. The building is constructed of masonry, with a steel frame, and metal cladding. In total, the building currently contains 3,862 windows on its facade and 4 banks of 8 elevators designed by Otis Elevator Corporation.[7] Crown ornamentation The Chrysler Building is also well renowned and recognised for its terraced crown. Composed of seven radiating terraced arches, Van Alen's design of the crown is a cruciform groin vault constructed into seven concentric members with transitioning set-backs, mounted up one behind each other.[27] The stainless steel cladding was ribbed and riveted in a radiating pattern and had many triangular vaulted windows, transitioning into smaller segments of the seven narrow set-backs of the facade of the terraced crown. The entire crown is clad with silvery "Enduro KA-2" metal, an austenitic stainless steel developed in Germany by Krupp and marketed under the trade name "Nirosta" (A German play-on-words for "nie rost", meaning "never rust") [28][29]. Observation and broadcasting When the building first opened, it contained a public viewing gallery on the 71st floor, which was closed to the public in 1945. The private Cloud Club occupied the 66th-68th floors, but closed in the late 1970s. The very top stories of the building are narrow with low sloped ceilings, designed mostly for exterior appearance with interiors useful only to hold radio broadcasting and other mechanical and electrical equipment.[7] Television station WCBS-TV (Channel 2) originally transmitted from the top of the Chrysler in the 1940s and early 1950s, before moving to the Empire State Building.[7] For many years, WPAT-FM and WTFM (now WKTU) also used the Chrysler Building as a transmission site, but they also moved to the Empire by the 1970s. There are currently no commercial broadcast stations located at the Chrysler Building. Lighting There are two sets of lighting in the top spires and decoration. The first are the V-shaped lighting inserts in the steel of the building itself. Added later were groups of floodlights which are on mast arms directed back at the building. This allows the top of the building to be lit in many colors for special occasions. This lighting was installed by electrician Charles Londner and crew during construction.[7] Appeal In more recent years, the Chrysler Building has continued to be a favorite among New Yorkers. In the summer of 2005, New York's own Skyscraper Museum asked one hundred architects, builders, critics, engineers, historians, and scholars, among others, to choose their 10 favorites among 25 New York towers. The Chrysler Building came in first place as 90% of them placed the building in their top 10 favorite buildings.[30] The Chrysler Building's distinctive profile has inspired similar skyscrapers worldwide, including One Liberty Place in Philadelphia. Cultural Depictions As an iconic part of the New York City skyline, the Chrysler Building has been depicted countlessly in almost every medium - film, photography, video games, art, advertising, music, literature, and even fashion, as its use quickly establishes without doubt the location in which the depicted events are occurring. In the music scene, Meat Loaf's 1993 album Bat Out of Hell II: Back Into Hell's cover art depicts a demonic bat clinging to the top floors of the Chrysler Building. The artwork was by done by Michael Whelan.[31] The Chrysler building is widely known to be depicted in many films, such as the 1998 film Deep Impact, where the wall of water that surrounds the skyscraper, people can be seen on the 61st floor observation deck fleeing to the other side of the building.[32] In another film, Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer, while Johnny Storm chases the Silver Surfer through Manhattan, The Silver Surfer flies straight through the Chrysler Building.[33][34] Towards the end of Steven Spielberg's A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, the Chrysler Building is seen totally submerged underwater as the aliens guide their spacecraft through the submerged ruins of Manhattan.[35] In the first movie series of Spider-man, Spiderman perched on top of one of the building's gargoyles, mourning of a beloved relative's murder.[35] Quotations Chrysler Building"Art Deco in France found its American equivalent in the design of the New York skyscrapers of the 1920s. The Chrysler Building...was one of the most accomplished essays in the style." —John Julius Norwich, in The World Atlas of Architecture "The design, originally drawn up for building contractor William H. Reynolds, was finally sold to Walter P. Chrysler, who wanted a provocative building which would not merely scrape the sky but positively pierce it. Its 77 floors briefly making it the highest building in the world—at least until the Empire State Building was completed—it became the star of the New York skyline, thanks above all to its crowning peak. In a deliberate strategy of myth generation, Van Alen planned a dramatic moment of revelation: the entire seven-storey pinnacle, complete with special-steel facing, was first assembled inside the building, and then hoisted into position through the roof opening and anchored on top in just one and a half hours. All of a sudden it was there—a sensational fait accompli." —Peter Gossel and Gabriele Leuthauser, in Architecture in the Twentieth Century "One of the first uses of stainless steel over a large exposed building surface. The decorative treatment of the masonry walls below changes with every set-back and includes story-high basket-weave designs, radiator-cap gargoyles, and a band of abstract automobiles. The lobby is a modernistic composition of African marble and chrome steel." —Elliot Willensky and Norval White, in AIA Guide to New York References ^ The Chrysler Building - SkyscraperPage.com ^ The World's Tallest Brick Building - SkyscraperPicture.com ^ A view from Above - The Chrysler Building ^ Emporis Data - See Tallest buildings Ranking ^ Emporis Data "...a celebrated three-way race to become the tallest building in the world." ^ The Manhatten Company - Skyscraper.org; "...'race' to erect the tallest tower in the world." ^ a b c d e f g h i j k University of Wisconsin-Madison; School of Engineering - The Chrysler Building ^ The Silver Spire; How two men's dreams changed the skyline of New York Paragraph 8. Author: James E. Beyer, American Institute of Architects ^ Emporis.com - Chrysler Building ^ Glass Steel and Stone - Chrysler Building & automobile parts http://glasssteelandstone.com/BuildingDetail.php?ID=436] ^ Emporis Data ^ The Chrysler Building, Creating a New York icon, day by day. Pages 54, 158, image caption no.39 ISBN 1-56898-354-9 ^ Emporis Data - See source no.4 line 4; "Briefly held the world's tallest title until it was eclipsed by the spire of Chrysler Building." ^ CTBUH - Criteria of World's Tallest Building ^ The Chrysler Building, Creating a New York icon, day by day. Page 161. Image caption no.39 - ISBN 1-56898-354-9 ^ The Chrysler Building, Creating a New York icon, day by day. Page 161, image caption no.54 ISBN 1-56898-354-9 ^ The Chrysler Building, Creating a New York icon, day by day. Pages xiii (Paragraph 10) and 161. Image caption no.39 - ISBN 1-56898-354-9 ^ http://www.jayebee.com/discoveries/criticism/silver_spire.htm. ^ http://www.signonsandiego.com/uniontrib/20050619/news_mz1h19chrysl.html. ^ http://kilroymetal.com/HTML/project_gallery.htm. ^ http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B06E7DB133BF936A35750C0A9679C8B63. ^ Chrysler Building. National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service (2007-09-11). ^ ["Chrysler Building", August 1976, by Carolyn PittsPDF (419 KiB) National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination]. National Park Service (1976-08). ^ [Chrysler Building--Accompanying 1 photo, exterior, undated.PDF (52.7 KiB) National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination]. National Park Service (1976-08). ^ http://altura.speedera.net/ccimg.catalogcity.com/220000/225900/225955/Products/9481499.jpg ^ http://www.imperialclub.com/Yr/1926/building/Cap.htm ^ The City Review.com - Chrysler Building by AIA Carter B. Horsley ^ http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2002/11/18/021118fa_fact_pierpont. ^ http://www.bssa.org.uk/topics.php?article=82. ^ http://select.nytimes.com/search/restricted/article?res=F70B13FC3C550C728CDDA00894DD404482 ^ A demonic bat on the top of the Chrysler Building ^ - Deep Impact - See plot keyword tags ^ Yahoo! Movies: Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer (2007) ^ Movielocationguide - Rise of the Silver Surfer filming location ^ a b The NY Times - In the Background, but No Bit Player Skyscrapers, Antonino Terranova, White Star Publishers, 2003 (ISBN-8880952307) |

|

| nyc-architecture.com | |