|

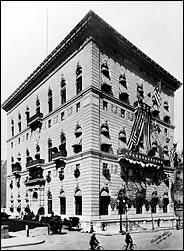

New York

Architecture Images- Midtown University Club |

|

architect |

Charles Follen McKim of McKim, Mead and White |

|

location |

One W54, at Fifth Ave. |

|

date |

1900 |

|

style |

Renaissance Revival the city's finest Italian Renaissance palazzo-style

structure "elements from the Palazzo Spannochi, Siena, and the Palazzo Albergati, Bologna, are freely quoted" Leland Roth |

|

construction |

masonry bearing walls, steel spans, conc "not limestone, as you might think, but pink Milford granite from Maine.There is a slight batter, or receding upward slope to the walls, adding to its austere majesty." John Tauranac |

|

type |

Club |

|

|

|

|

|

|

"...The plan was organized around an enclosed

cortille that received different treatment on alternating floors,

beginning as a full colonnade on the first floor, becoming a three-sided

colonnade on the second floor and shrinking to four piers on the third

floor....The centerpiece of the design, appropriate for a club of

learning, is the library on the second floor, and here no expense was

spared. In a long, barrel-vaulted room with cross-groin vaults,

...supposedly Le Corbusier on a visit in 1935 declared he could

understand how one would become a Beaux-Arts architect, or as he wrote:

'In New York, then, I learn to appreciate the Italian Renaissance. It is

so well done that you could not believe it to be genuine. It even has a

strange new firmness which is not Italian, but American.' "

—Richard Guy Wilson. McKim, Mead & White Architects. p186-192. |

|

|

The Perfect Picture Of an Urban Club

By CHRISTOPHER GRAY Published: May 8, 2005   THE network of steel scaffolding now encasing the University Club at 54th Street and Fifth Avenue seems to offer a new sense of scale to the Italian Renaissance-style palace. Built in 1899, it remains one of New York's most majestic monuments. The University Club was founded in 1865 by a group of recent college graduates who hoped to extend their collegial ties. After several moves, the club took over an existing town house at 26th Street in 1883 and Madison Avenue, where it prospered. At that time, however, Manhattan's social center was beginning to move uptown. In the early 1880's the Vanderbilt family built half a dozen large mansions along Fifth Avenue from St. Patrick's Cathedral at Fifth Avenue between 50th and 51st Street, up to the Grand Army Plaza, between 58th and 60th, securing the strip as the most imposing residential address in New York. One block in this section, however, the west side of Fifth Avenue from 54th to 55th, remained nearly unimproved. It was occupied by St. Luke's Hospital, set well back from the street and surrounded by a large lawn. In 1893, St. Luke's announced that it would move up to its present location on West 113th Street, setting off speculation as to who would acquire the site, and for what purpose. The younger members of the Union Club, the most important social club in New York, had, according to The New York Times in 1896, "set their hearts" on the 54th Street corner of the plot, but older members of the club resisted the move. The University Club, with its membership limited by the size of its building to 1,500 members who were residents of New York City and 900 who lived elsewhere, was looking for a larger space, because it had nearly 600 people on a waiting list to join. It acquired the St. Luke's site and proceeded to build what remains the most imposing of the city's social clubs. It chose the location, according to The Times, after passing on two southerly corners farther downtown as "the wrong corners," an indication that sun falling on the northeast and northwest points of an intersection made them especially desirable. The architecture firm of Charles McKim, William Mead and Stanford White, who were all members of the University Club, got the architectural commission to design the new club. McKim designed a $1 million building, which still sets the standard for large urban club buildings. The day of the low-rise club - like the three-story Century Association built in 1891 on West 43rd Street - was passing, and McKim built a six-story building that appeared to be only three by using high, arched openings. Earlier in the decade, White had gotten the commission to design the Metropolitan Club at 60th Street. For the University Club, McKim chose a cool pink granite, very different from the soft, rich marble that his partner had chosen for the Metropolitan Club. Probably to soften the effect, McKim had most of the blocks tooled, roughening the surface, and also provided a series of balconies with lush bronze railings and a richly modeled cornice. Rows of smaller windows for the additional floors were set in at the level of the main frieze at the top, as well as two lower friezes of seals of various colleges. Such a large building permitted a complex plan, but it is organized around the three-floor conceit of the main facade. On the ground floor, the large central entry court is surrounded by giant green Connemara marble columns 25 feet high. Along the Fifth Avenue front runs a great red and gold lounging room, with windows starting at the floor. Members are sometimes visible through the windows, reading newspapers in deep chairs and sometimes dozing, the perfect picture of a traditional urban club. The next level of high arched windows contains the club's great library, a long room with a vaulted ceiling running along 54th Street. Organized into alcoves, the double-height book stacks have small balconies reached by tiny staircases, all underneath a sparkling series of ceiling paintings and embossed decorations by H. Siddons Mowbray. If the lighting is right, these also can be glimpsed from across the street in the evening. The highest main level holds the dining room, a vast wood paneled space with columns at each end and a coffered ceiling; although it does not appear in Zagat's, it is one of the most elegant eating places in New York. All floors are connected by elevators. The club's strategy of building a larger home worked: in 1903 membership was near new, higher, limits - 1,695 New York City residents out of a cap of 1,700 and 1,105 nonresidents out of a limit of 1,300. Those newly elected paid an entrance fee of $200 and annual dues of $60. The University Club is generally considered one of the masterpieces of the famous architectural partnership. At the time, there was little criticism of the building, although comments published anonymously in the trade journal Real Estate Record & Guide called the building "a splendidly obvious piece of work" that would be favored by "the steady person with a safe habit for the obvious." Recognizing McKim's skill at disguising six stories into three, the writer questioned the very premise of why an architect should have to camouflage the actual height of such a building. It noted the unyielding nature of granite, despite the balconies and ornamental carving, saying the new club displayed "a certain flatness of surface despite the attempt, or more accurately, because of the attempt at the contrary." The club opened in 1899, just as real high-rise construction got its toehold in that neighborhood. The Gotham Hotel, now the Peninsula New York, opened on the north end of the block within a few years. Its architect, Hiss & Weekes, made no attempt to disguise the hotel's 18 stories, but did make the stone courses of the new building line up with the club, although a softer, more luxurious limestone was used. Over the decades the facade of the University Club became dark with soot, but it was cleaned in the mid-1980's. That was not necessarily an aesthetic improvement: the old facade had aged to charcoal gray, like a top quality wool. Cleaning exposed the original granite, and all the subtlety of the stonework's age was lost. The scaffolding put up late last month will provide access for repair crews who are going to remove the massive balconies to inspect their fastenings, according to Jonathan Raible, one of the architects working on the job. At the same time the bronze railings will be removed, cleaned of soot deposits and coated with wax. Although the original architects did not plan for the stone to be soiled, they did anticipate the natural oxidation common to bronze, and Mr. Raible says that his project will preserve the rich, dark green stain of the metal, which otherwise takes 20 to 25 years to develop. Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company |

|